Why Kids Invent Imaginary Friends

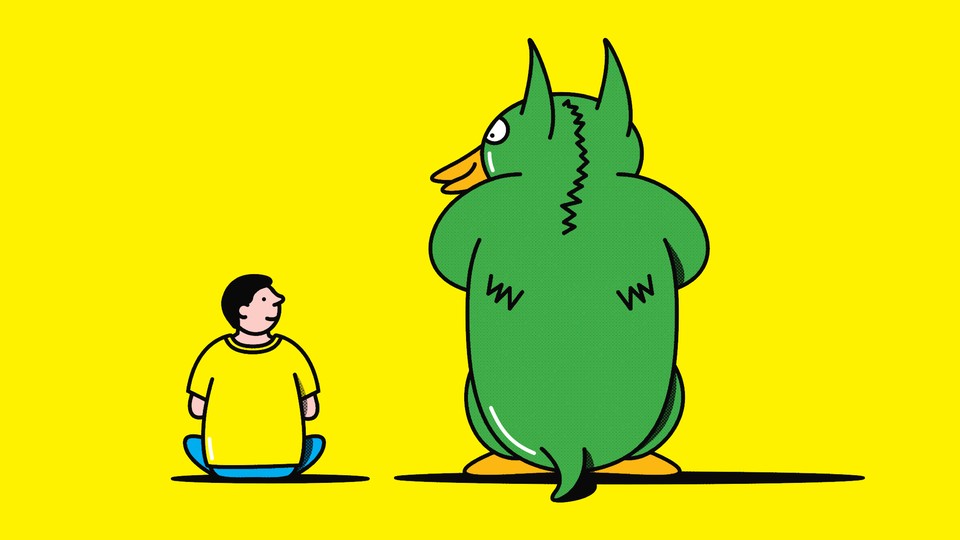

Make-believe companions can teach children more than just how to play pretend.

On a recent Monday morning, 10-year-old Sasha told her mother about the current drama between her two best friends. Tentacles, a giant Pacific octopus, had told Sasha that he was in love with Coral, who is also an octopus, but who has “one extra tentacle that she’s learning how to use,” per Sasha. Coral was unaware of Tentacles’ infatuation, but had relayed a similar message to Sasha: She had strong feelings for Tentacles but was too shy to tell him. Sasha was stuck in the middle.

This romantic drama was news to Sasha’s mom, Charli Espinoza. “Oh my gosh, Sasha!” Espinoza, 39, said. “I didn’t know.”

Talk of Tentacles and Coral is common in Espinoza’s central-California home, from their intergalactic adventures to their love lives. Though the octopuses live with Espinoza, Sasha, and her 12-year-old sister, Emily, only Sasha knows what they look like. They are, in Sasha’s terms, “creatures of imagination,” or imaginary friends.

Sasha’s coterie of creatures of imagination also includes Cherry the reindeer, Vanity the manatee, and Toua the therapy mosquito, who stops the spread of malaria. Tentacles is the crew’s ringleader and was Sasha’s first imaginary friend, who came to life after tentacle-like shadows danced across Sasha’s bedroom wall one night when she was 6, Espinoza says.

Over the years, Tentacles has developed a personality—thoughtful, timid—and provided both physical and emotional comfort for Sasha, who suffers from chronic migraines. “She loves telling stories, and that’s one of the ways she manages pain,” Espinoza says. “She’ll talk about what’s happening in great detail and that really helps her.”

The creatures of imagination have become a source of camaraderie for Sasha, who has autism, is homeschooled, and doesn’t often interact with other children.“They’re here to help me when I’m not feeling good and to talk to me when I'm lonely and Emily doesn’t want to play,” Sasha says, “and to go to space with me.”

Imaginary friends are a common—and normal—manifestation for many kids across many stages of development. In fact, by age 7, 65 percent of children will have had an imaginary friend, according to a 2004 study. Stephanie Carlson, a professor at the University of Minnesota’s Institute of Child Development and one of the study’s co-authors, says that the prime time for having imaginary friends is from the ages of 3 to 11.

While psychologists agree that the presence of imaginary friends should not cause parents concern, what is less understood is what prompts children to create these personas or why some kids invent them and others don’t, says Celeste Kidd, a professor of psychology at UC Berkeley and the primary investigator at the Kidd Lab, which studies learning throughout early development. “For the most part, there’s no widespread consensus on what triggers it,” Kidd told me. “There is, however, widespread consensus on it being a normative part of development. Not all kids have imaginary friends, but it’s very common and neither problematic nor a sign of extra intelligence.”

Imaginary friends are a symptom of developing social intelligence in a kid. For children to dream up peers, they must understand that people possess beliefs and desires and exhibit behaviors that differ from their own, a concept called “theory of mind,” Kidd said: “Understanding that somebody else can want something different than you want or can know something that you don’t know is something that doesn’t start to emerge until around 4 or 5.”

A handful of small studies have tried to dig into the psychology of kids with imaginary friends. One suggested that relationships with invisible beings fulfill a child’s need for friendship and are more common among firstborn or only children. Research has also suggested that girls are more likely to conjure imaginary friends and that kids who have imaginary friends grow up to be more creative adults than those who do not. In Carlson’s studies, she’s observed that little girls typically take on a nurturing, teacherlike role with their imaginary companions, who often take the form of baby animals or baby humans. Little boys’ imaginary friends are frequently characters who are more competent than they are, such as superheroes or beings with powers, she says.

Imaginary friends help kids fulfill the three fundamental psychological needs laid out in self-determination theory, Carlson says: competence, relatedness, and autonomy. Children feel competent when they assume a leadership role with their imaginary companions—that is, describing their invisible pals as “dumb” or having to teach them a skill. Although their companions are make-believe, children relate to imaginary beings in the same way they connect with real friends. (Though imaginary ones come with the added benefit of allowing kids to simulate social situations with zero consequences, Kidd said.) And imaginary friends facilitate autonomy when children use their existence to manipulate a situation, such as insisting that parents serve their imaginary companions dinner or buckle them into a car seat. “Imaginary companions are giving kids a sense of control,” Carlson says. “They get to conjure them up, they get to make up the stories, they’re not being intruded upon by others. It’s something they can own all to themselves. It’s an interesting way to take a little bit of control back. But it can be very frustrating for the parents.”

Anna Sale, the creator and host of the Death, Sex & Money podcast, knows this feeling all too well. When her 3-year-old daughter June’s imaginary friend Salad, a 4-year-old with red hair, first “appeared” in their Berkeley home in February, she was the family member preventing everyone from walking out the door on time. June would inform her parents of Salad’s desire to join family outings but that she needed a little encouragement to hurry her along. “When Salad first showed up, there was a period where we couldn't leave the house, so we’d all have to say ‘C’mon, Salad!’ and wait for Salad before we left the house,” Sale, 38, says.

But for the most part, Salad is a welcome—and entertaining—addition to the family. Salad has a little sister named Book, and parents named Bobby and Eve (Eve is also the name of June’s newborn sister). They all live across the street, in a house with a windmill. For the most part, Salad doesn’t speak unless spoken to and is a mostly omnipresent companion for June. (While June and her family were recently on a road trip, Salad hung back in Berkeley.) But her existence, Sale believes, is helping June learn about friendship and storytelling.

The novelist K. B. Hoyle’s youngest child, Edmund, first befriended an invisible merman/vampire named Ed shortly after turning 4. Hoyle, 36, believes that Ed, who has the head of a vampire and the body of a fish, serves as a form of wish fulfillment for Edmund, who used to go by Ed. “Something [Edmund] said over and over again is ‘Ed has a fridge that never runs out of food,’” Hoyle told me. “Edmund would eat 36 hours a day if I let him. He wants Ed to have what he doesn't have, apparently.”

Though Hoyle and her family live in Alabama, Ed resides in South Dakota, in a giant house occupied by ghosts. Hoyle credits this detail to a road trip the family took to Badlands National Park last summer. To entertain her four sons during the long drive, Hoyle played an audiobook of The Hobbit. Once they were back home, Edmund pointed to a poster of The Hobbit’s cover art that hangs in Hoyle’s office, called it the Badlands, and claimed that Ed lived there.

Many aspects of a child’s life—from fictional characters to real experiences—often trickle into play, which includes imaginary friendship. “It’s an awareness of what’s going on around them,” Kidd said. “That can include things like what's in the news, but it can also include what’s going on in their lives.”

Seven-year-old Ari’s life is direct inspiration for his invisible buddy Davin. “Whatever I do, he does, so we kind of copy each other,” Ari says. Davin first emerged when Ari was 3, right after his mom, Katie Trudeau, gave birth to her second child, and at 2 inches tall, he is truly Ari’s mini-me. Sometimes, when Davin’s cold, he’ll jump into Ari’s pocket.

The crossover between the lives of imaginary friends and the real world can provide opportunities for life lessons. Davin’s existence has allowed Ari to approach sensitive topics. Recently, Ari came to Trudeau with a predicament: Davin was upset that his dad, whom Trudeau has never “met,” is a smoker. To Trudeau’s knowledge, no one in her son’s life smokes cigarettes, so the subject matter caught her off guard, “but I took advantage of it and said smoking’s bad and this is why,” she told me. “And we have Davin to thank for that.”

For parents such as Trudeau and Espinoza, it can be hard to fathom a day when the imaginary characters who’ve been populating their lives for so long simply cease to exist. Espinoza has grown particularly fond of Tentacles, the octopus. He’s been a good influence on the whole family, she says—teaching her daughters about compassion and friendship—even if her youngest daughter is the only one who can actually see him. “You know when you meet a cool person who’s doing interesting things, they've traveled to interesting places, and they know cool foods, and they're really nice to people?” Espinoza says. “That’s who Tentacles is.”