My first home was a house called Slieve Moyne in the village of Woodhall Spa, in Lincolnshire. In later years I would think of the place as Tatooine, the planet Luke Skywalker imagines to be furthest from the bright centre of the universe. But for now, it was the universe and one with which I was perfectly content. There was just one problem. When we first meet Luke on Tatooine, he has an issue with his mysteriously absent father. My father, on the other hand, was all too present. And his name might as well have been Darth Vader. Actually it was Paul. It’s a silly comparison of course. Dark Lords of the Sith aren’t constantly wasted.

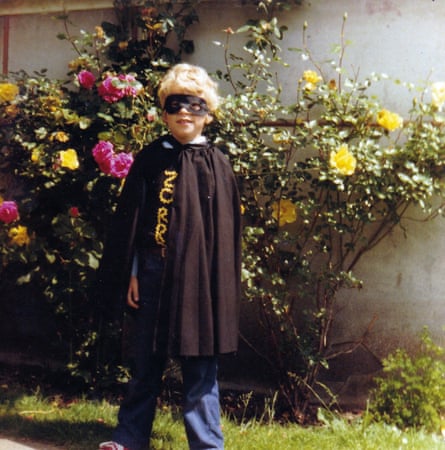

It’s the mid-1970s and I live with Mum, Darth Vader and my two older brothers, Mark and Andrew.

Imagine a child’s drawing of a house. This one would show three bedrooms upstairs, the little one with Rupert the Bear wallpaper for me, the middle one for the grownups and the one at the other end containing Mark and Andrew wearing denim waistcoats and walloping each other with skateboards (because that’s what Big Brothers do). There is smoke coming out of the chimney, as it should in all drawings of this kind; in this case provided by Darth holding double pages of the Daily Mail against the fireplace to encourage the flames. Sometimes he gets distracted while doing this because he’s shouting at James Callaghan on TV, and the paper catches fire. He has to throw the lot into the fireplace, which, of course, sets fire to the chimney.

He has laid the fire using the logs and sticks that he chopped up with the chainsaw left leaning against the back door, the one he uses for his job as a woodsman on the local estate (my Daddy is a woodcutter). The Mummy will be in the tiny kitchen, standing over an electric hob (because that’s what Mummies do) and stirring Burdall’s Gravy Salt into a saucepan of brown liquid.

It’s a static picture, of course, so we can’t see that the Mummy’s hands are shaking because she knows that the Daddy has spent all afternoon in the pub and has come home in one of his “tempers” (because that’s what Daddies do). If, during tea, one of the Big Brothers speaks with his mouth full or puts his elbows on the table, the Daddy has been known to knock him clean off his chair. The Mummy will start shouting at the Daddy about this but, of course, she can’t shout as loud as the Daddy. No one can shout as loud as the Daddy or is as strong as the Daddy, which is why the Daddy is in charge. The Little Brother will start crying at this point and will most likely be told to shut up by the Big Brothers who are themselves trying not to cry because that’s another thing that they’ve learned doesn’t go down well with the Daddy.

I remember the summer’s day when I was watching the Six Million Dollar Man battling with Sasquatch and the following moment I was being lifted an impossible number of feet into the air and thrashed several times around the legs with a pair of my own shorts that had been found conveniently nearby. Dropped back on the settee, I looked at those navy-blue shorts with a baffled sense of betrayal. They were my shorts. My navy-blue shorts with the picture of Woody Woodpecker on the pocket. And he’s just hit me with them. Maybe in the seconds before I was watching Steve Austin, I’d spilt something or broken something. Maybe I’d got too close to the fire or the chainsaw. Who knows? Actually telling a child why he was being physically punished was somehow beneath the dignity of Paul’s parenting style.

There are happy early memories from Slieve Moyne too, of course. Singing along with Mum whenever her beloved Berni Flint appeared on Opportunity Knocks; the thrilling day the household acquired its first Continental Quilt (a duvet), which my brothers and I immediately used as a fabric toboggan to slide down the purple stairs; playing in the snow, playing in the garden – all the sunlit childhood fun you’d expect from times when Dad was out.

Best of all was sitting on the back seat of the car, Mum driving us between the golf club where my grandparents (and Auntie Trudy) work in the kitchen and our new bungalow in the next village. It’s a journey we made many times a week and the tap of her wedding ring on the gearstick is one of the happiest sounds of childhood. It means that I’m alone with Mum.

“Quiet boy”, “painfully shy”, “you never know he’s there”: these are some of the phrases I catch grownups using when they talk about me. But not here, not in the car with Mum. And definitely not when Sailing by Rod Stewart comes crackling over the MW radio. The gusto of our sing-a-long is matched only by the cheerful lousiness of my mother’s driving.

“We are SAAAAILING” (tap, second gear), “we are SAAAAILING” (tap, into third), “cross the WAAAATER, tooo the SEEEA” (tap, stall, as she tries to take a left turn), “we are sail –” (tap, handbrake, ignition), “we are s –” (tap, ignition, choke, window-wipers), “to be NEEEAR you” (triumphant restart, cancel window-wipers, tap, crunch into first), “to be FREEE!”

I like it here. There are no men, and there are no other boys. I don’t seem to be very good at being a boy and I’m afraid of men.

One man in particular.

To be fair, there were moments when he was affectionate. For example, if he was in a good mood he might crouch down in front of me, put his massive fist under my nose and say in a joke-threatening way, “Smell that and tremble, boy!” For years I wasn’t quite sure what this phrase meant – “smellthatandtremble” – it was just a friendly noise that my dad made when he was trying to make me laugh. Oh, and I laughed all right. I mean, you would, wouldn’t you?

But in general, I’m afraid my memories of those first five years in that house tend towards the nature of a bad dream. To avoid real bad dreams, the trick was to make sure there was a gap in my bedroom curtains where the light could come in. But the real problem was not avoiding the night-time imaginings but the daytime reality. Not the Phantom, but the Menace. And he was unavoidable.

A classic of this sci-fi/horror genre was the episode called “Do an eight, do a two”. This family favourite has me, aged five, sat in the living room with a pencil and paper, being yelled at by Dad to “DO AN EIGHT! DO A TWO!” It had come to his attention that I wasn’t doing very well in my first year at primary school and that, in particular, I was unable to write the numbers 8 or 2. Actually, I could write an 8, but I did it by drawing two circles, a habit which Mrs Morse of St Andrew’s Church of England Primary School found to be lacking calligraphic rigour. Anyway, the rough transcript of “Do an eight, do a two” goes like this:

Dad: DO AN EIGHT! DO A TWO!

Mum: He’s trying! There’s no point shouting!

Dad: JUST DO AN EIGHT!

(Five-year-old, sobbing, does an eight with two circles)

Dad: NOT LIKE THAT! DO A PROPER ONE!

(Five-year-old dribbles snot on to the paper and does some kind of weird triangle)

Dad: WHAT’S THAT MEANT TO BE? DO AN EIGHT!

Mark: Or a two!

(Eleven-year-old Mark, desperate for any rare sign of approval from Dad, has joined in)

Dad: WHY CAN’T YOU DO ONE? JUST DO AN EIGHT!

Mark: Or a two if you like, Robbie! Why not do a two, probably?

(Mum takes five-year-old on her lap. Five-year-old thinks it’s over)

(Comedy pause, titters from the studio audience)

Mum: Try and do a two, darling.

(Five-year-old freaks out. Then somehow manages a wobbly two)

Dad: DO A TWO!

Mum: HE’S DONE A BLOODY TWO!

Dad: DO ANOTHER ONE!

Mark: Or an eight!

You might be thinking “this is nothing” compared to your own experiences with a domestic hardcase. Or maybe you’re wondering how my mother put up with it for an instant. The truth is, we were all terribly afraid of him. In any case, Mum was probably just biding her time at that point. She had already made her plans. Before the end of that first school year, she divorced him and he moved out.

**************

I started keeping a diary after my 17th birthday. Early in March 1990 I wrote:

“My concern for Mum deepens. I’m quite ashamed to realise that this is the first reference in this diary to worrying about anyone but myself. Mum has been in hospital since last Friday with what was supposed to be a chest infection. In fact she has a few cancerous cells on her lung. She might have to have chemotherapy. Jesus Christ I’m so worried – I love her so much. I must resolve to be less selfish, to talk to her about things more often. Life without her is unthinkable. Literally unthinkable.”

And then, at the end of an entry a few weeks later:

“Found out for sure, the week before last, on Wednesday March 21st, that Mum definitely isn’t going to recover. She has about four months. I don’t want to talk about it. Even to you.”

That day, I had arrived home from school and felt a sudden tightness in my chest. Dad’s van was parked neatly outside the bungalow.

Dad is at the kitchen table with Derek, Mum’s second husband. He starts talking and the world ends.

“Y’mum’s poorly, boy. It’s terminal.”

You can get quite a lot of juice out of that word “terminal”, if you speak with a Lincolnshire accent and are quite drunk. The way he says it, the “er” sound is dug from the very depths of his diaphragm.

I look across at Derek, who is leaning an elbow on the table with a hand covering his mouth. He nods a tiny confirmation. Incredibly, somewhere in the room, Dad is still talking. “It’s ’orrible, boy, but that’s life. Now, I don’t know if you want to come and live with me or … ” he looks around the kitchen, “I mean, you’re probably going to need a cleaner, Derek, because … well, it’s hard keeping a place clean.” Derek nods. “Josie, who cleans my house, she could probably come and do a couple of hours a week.”

Derek says, “What does she charge, like?”

“Well, I give her a fiver, mate.” Derek is alarmed by the prospect of paying Josie £5 and he’s about to haggle, but stops because he’s noticed I’m crying.

“I know, boy,” Dad says, “it’s ’orrible.”

Here I am then, with Mum about to vanish, stuck here in the kitchen with the Idiot Brothers talking about Dad’s cleaner.

When Dad leaves, I notice that on the side of the van is painted the name of his business, which today looks less like an advertisement than like a rare flash of self-awareness: Paul Webb, Ltd.

I’m next to Mum on her bed, later that day. With effort, she draws herself up on her stack of pillows. “I’m sorry, darling, that wasn’t a very nice way to find out. I should have told you myself.”

I make an ineffectual gesture to help with the pillows but I’m scared of getting in her way. She’s got Dallas on the portable telly with the sound turned low. Bobby Ewing is having a long meeting with assorted oil barons.

“Don’t worry about me,” I say. Her skin is a yellow-grey now and at the top of each breath there’s a distant gurgle which gets closer by the week. All the signs that I chose not to see suddenly reveal themselves with pathetic eloquence. She’s obviously dying.

She says, “Now then, is there anything you want to ask me? Or is there anything you want to say to me?” I feel a thousand future selves lean in to listen with interest. I rack my brain: there is no question up to the task and no statement either, apart from “I love you”, but I don’t trust myself to say that without losing it. I don’t want to do that; I’m her son and I want to be strong. So I say the thing that bothers me most about being 17 and me.

“I suppose … I mean, this isn’t important.”

“Go on … ”

“I’m a virgin.”

She starts to smile, but doesn’t want to look like she’s taking the piss. Also, smiling takes effort and she’s working hard to talk. She says, “I won’t say I’m surprised; I won’t say I’m not surprised. But you’ll catch up.”

“All my mates have got girlfriends.”

“You’ll overtake them. In everything.”

This emboldens me, so I try a promise. “I’m going to get three As and go to Cambridge, Mum.”

She’s ready for this one. “I know you’ll be happy wherever you end up, Rob. I’m proud of you already, so don’t worry.”

**************

What are we saying to a boy told to “man up” or to “act like a man”?

Often, we’re saying, “Stop expressing those feelings.” And if a boy hears that enough, it actually starts to sound uncannily like, “Stop feeling those feelings.”

It sounds like this: “Pain, guilt, grief, fear, anxiety: these are not appropriate emotions for a boy because they will be unacceptable emotions for a man. Your feelings will become someone else’s problem – your mother’s problem, your girlfriend’s problem, your wife’s problem. If it has to come out at all, let it come out as anger. You’re allowed to be angry. It’s boyish and man-like to be angry.”

When people saw Dad walking down the street in Woodhall Spa, they did not think: “Ah, there goes Paul Webb, a walking powder-keg of repressed grief.” Paul’s public face was beloved by more or less the entire village. Generous with his time, charismatic, cheeky, and straightforwardly kind. Everyone adored him. But then, they didn’t have to live with him.

**************

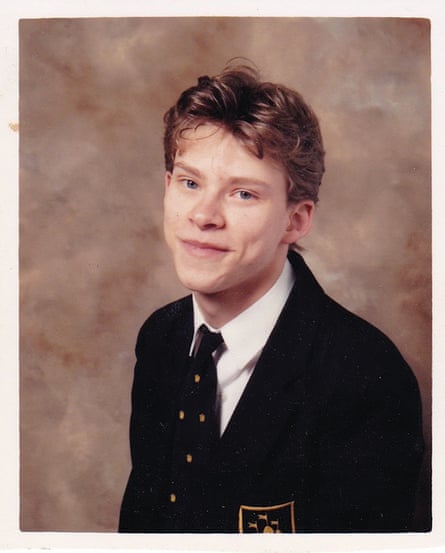

Mark drives me directly to school from my mum’s funeral. My Queen Elizabeth Grammar School sixth-form blazer and tie are both black and so, this morning, I had an off-the-peg funeral costume so long as I unpicked the gold badge from the blazer.

I had the badge in my back pocket during the funeral. I sew it back on in the car, quickly and about as well as you’d expect for someone who would normally have asked his mum to do it.

There’s a lower sixth form trip to Nottingham, to a university fair. It’s a sort of open day where many university admissions officers will be gathered in a big hall to hand out prospectuses and have a chat. I don’t want to miss it.

In Nottingham, the university reps are seated behind desks around the sides of a huge hall to talk to A-level students from far and wide. The longest queues are to see the guys from Nottingham or Leicester Polytechnics (they become universities a year later), followed by a medium number for big civic universities like Leeds and Manchester, a shy smattering for Bristol and Durham and then … I peer into the far corner – ah yes. A grey-haired lady with a Cambridge sign on her desk is sitting completely alone.

I start walking towards her, wondering who the hell I think I am.

I hover awkwardly next to the empty seat across from her. She looks up suddenly and says “Please!”, gesturing to the chair.

I take the seat, saying, “I … I just thought I’d … say hello.”

“I’m glad you did.” She gives me a conspiratorial smile and waits. I don’t have a thought in my head. “Well, I’m doing my A-levels … ” Oh, you dick. Every fucker in the room is doing their A-levels. “ … and erm … ” I go completely dry.

“And you have an interest in applying to Cambridge,” she offers.

“Yes!” I almost shout with relief and embarrassment. I’m actually blushing. This was a terrible idea. Just keep talking. “I’m only at a grammar school… ” “Which one?”

“Er, it’s in a market town in Lincolnshire. I mean, it’s only … ”

“Queen Elizabeth’s. In Horncastle.”

I stare at her. “Yeah. You’ve heard of us, then.”

“We’ve heard of everyone.”

Oh my God. She’s going to recruit me as a spy! Do I want to be a spy?! No, not really! I’m still looking at her, dumbfounded.

“And is there a particular subject you’re interested in studying at Cambridge?”

I wish she would stop saying Cambridge. People will hear. “English.”

“My own subject. And a particular college?”

“King’s.”

“My own college! Well, now!” If this were a first date, it would be going quite well.

“The thing is … I only got four As and four Bs for my GCSEs. So, y’know, nothing to write home about.”

She gives a little chuckle. “But nothing to be ashamed of. I assume one of your As was in English?”

“Yes.”

“And you’re doing English at A-level.”

“Yes.”

“And you expect to get an A in that.”

“ … Yeah, I do actually.”

“And you could manage one more A grade? Another A and a B, possibly?”

My confidence evaporates and suddenly this is ridiculous.

AAB? I haven’t finished an essay in five weeks.

“Well, that might be … it’s been a bit tricky lately. It’s sometimes hard to get started, what with … I mean, like this morning, it’s not as if … ” I can hear my voice start to wobble.

She’s frowning in concern and puts her palms flat on the table. “What was it about this morning? Sometimes if we can identify a particular barrier to … ”

“Well, this morning doesn’t really count because it was my mum’s funeral. But generally, I’ve just found it … ”

“I’m sorry, did you say that this morning was your mother’s funeral?”

“Yeah.”

“This morning?”

“That’s right. So it’s all gone a bit … I feel stupid for even thinking about … your … university.” She’s looking at me with a level of compassion that makes me want to tell her to cheer the fuck up. I blink at the wall behind her, feeling dizzy, and put a hand on my edge of the table to steady myself, even though I’m sitting down.

She says, “I’m very sorry to hear that news. May I at least offer you some reassurance, erm … ?”

“Robert.”

“Let me at least say this, Robert. I’m Catherine, by the way. You’re sitting in the right chair, talking to the right person. It’s not stupid in the slightest for you to think of us.”

Catherine talks briefly about open days and how I ought to come and have a look around at least two colleges. Then she reaches across and gives my hand a quick squeeze. “Good luck.”

Back at school, I wait till no one else is in the form room and ask my English teacher Mrs Slater if it’s ridiculous for me to think of Cambridge. “No, not ridiculous,” she says quickly, and then, “We’ve certainly sent dimmer people than you there.” This is encouraging. “Although,” she adds thoughtfully, “not for quite a while.”

**************

“Dad, can we have a quick word?” This is the first time I’ve actually asked to talk to him about anything. I got the offer of a place from Robinson College, Cambridge. But then my A-level grades didn’t cut it.

“Erm, you know you said that I could come and live with you if … ”

“Yes?!”

“Well, if the offer’s still open … ”

“Oh, YES mate! Good old boy! You don’t need to ask, bo – Rob. It’s your home, Rob. Good!”

“It’s just I’ve got to retake these exams and … ”

“You can have your old room, mate. Now, it’s mucky as hell at the minute because I’m propagating marigolds in it, but I know exactly where to put them. When are you thinking of moving in?”

“Well, I need to tell Derek. It’s really only for a few months, what with these exams and … ”

“Derek been driving you up the wall. And little Anna-Beth, bless ’er. It’s not what you NEED, is it, boy? You need some bloody PEACE, mate. For your exams!”

“Yeah.”

“Now my lady-friend Delia comes to stay with us a few days a week, but we won’t mind her. You remember Delia, boy?” Ah yes, Mum used to call her Delilah.

“Yep.”

“She’ll not bother you, mate, you do your own thing.”

I say, “So I’ll tell Derek tonight and p’haps move in at the weekend.”

“Righto, boy.”

I break the news to Derek that night and he makes it easier for me by saying all the wrong things. “Well, y’poor old mum wanted you to stay here with us.”

This is how he’s been referring to Mum for the last 16 months – “y’poor old mum”. I suppose it’s meant with love, but the condescension of it drives me nuts. In my memory, she’s alive and well, not poor and old.

“Anna-Beth’s gonna miss yer.” I take another breath. I feel terrible about my little sister. It doesn’t occur to me that when he says she’s going to miss me, he’s actually saying that he’s going to miss me. If he liked me that much, why had he been so annoying? In fact why is he being so annoying now?

The priority now in the masculine mind of the boy who claims he doesn’t like masculinity is to become angry with Derek. Obviously I’m still heartbroken about Mum, so I’m angry with Derek. I feel guilty about abandoning Anna-Beth, so I’m angry with Derek. I feel sorry for Derek, so I’m angry with Derek. There again, even if I noticed any of this, I wouldn’t share it with Derek because I’m obviously afraid of upsetting Derek, which itself makes me angry with Derek.

Now that I am a man, I have graduated to an advanced level of blaming other people for unwanted feelings.

I say, “I just need a change of scene.”

**************

After another stretch of consistently failing to do any revision, and then pulling out of my November resits, I go home to tell Dad that I’m going to be living with him for another seven months. I’ll do my “straight-talking” – short, concise sentences, fairly loud. He appreciates that.

“Dad, I haven’t been very honest with you about the amount of work I’ve been doing.”

“Righto, boy.”

“I’ve actually done nothing.”

“OK.”

“I’ve found it really hard to concentrate. I don’t know why – maybe I … ”

“Y’mum just died, mate.” He says it like it’s the most obvious reason in the world, which it suddenly is. So much for my straight-talking. I wasn’t expecting this.

I say, quietly, “Yeah, but that was over a year ago.”

“It was yesterday, boy. Might as well have been yesterday.”

He’s still grieving too. I had no idea.

“It’s ’ard, Rob, what you’re doing. I couldn’t do it. I was a dead loss at school.”

“Beaker says it’s curtains for Cambridge.”

He looks up. “What does that wally know?”

“Well … he knows quite a lot, but … we’ll see.”

“We will see, boy. We will. ‘Curtains’,” he says. Bugger Beaker.”

**************

Next year Dad is driving his Vauxhall Cavalier with Mark in the passenger seat. I’m crammed in the back, along with a massive suitcase and a new but artfully battered rucksack. Normal service has been resumed: Dad completely lost it trying to take the front wheel off my bike before stuffing both parts into the boot.

“What do you think the bird situation will be like at Cambridge then, Bobs?”

Luckily, I’ve never called them birds out loud, so I won’t have to adjust that bit of vocabulary. I’ve been practising for years talking the way I think a Cambridge student talks, but only to a selected audience – Carole, Heather Slater and a couple of other teachers.

I’m currently under the impression that it’s all to do with irony and detachment. I think that whatever they say, clever people don’t mean it. I expect in the next hour to be in the exclusive company of people who would never dream of calling a spade a spade. The very idea! Surely, it’s all going to be rather camp. And by the time we pass Huntingdon, my accent is finally in line with the geography of England. It was a good four years ago that I started to say “carstle” instead of “caastle” and “ahp” instead of “oop”. All the affectations are coming home, I think. To the place where they won’t be affectations any more. No more pretending.

We find my room at Robinson College and Mark and Dad nearly piss themselves when they see a note on the bed, reading “YOUR BEDMAKER’S NAME IS ALISON”. Finally, Little Lord Fauntleroy has staff.

I walk them back to the car. Mark now has business cards and he gives one to me. On the back, he’s written, “Whatever the time, day or night, if you need me, give me a call.” It occurs to me for the very first time that he’s worried about me being here on my own in this new place where he can’t keep an eye out for me. I thank him, even though the guilty truth is that I’ve been at Robinson for 10 minutes and haven’t felt safer or more at home since Mum died.

“Right then, boy,” Dad says. “See you at Christmas. Try not to get VD. Good luck with it all, me old beauty.” He’s looking emotional too, but mainly he’s already annoyed about the drive home, as is poor Mark. We shake hands. They get in the Cavalier and I wave them off until the car is out of sight.

It’s a pity I’m wearing trainers because I have no heel to turn on. I turn anyway, put my hands in my pockets and saunter up the brick walkway of the main college gate. I didn’t give Darth much of a battle. This will be different. I can stop worrying about how to be a boy. I can stop showing off about how not to be a boy. I’ll just be myself. That shouldn’t be too difficult, should it?

The above is an edited extract from How Not To Be a Boy, published 29 August by Canongate (£16.99). To order a copy for £12.74 go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99

Click here for information on Robert Webb’s event dates, including Edinburgh International Book Festival, go to canongate.co.uk.

Webb’s new sitcom, Back, also starring David Mitchell, begins on Channel 4 this autumn.

Q&A with Robert Webb

You evoke growing up in a small town very vividly. How much do you think it has stayed with you?

That thing about it being closed in: when it all started to go well for me and David [Mitchell], and I got a little bit of profile and a tiny bit famous, it was very familiar, because it was just like living in Woodhall. That sense of surveillance was not new. You’d come home and Dad would say, “So-and-so says you were in the bakery today, getting a ham roll. Because we’ve got some ham in the fridge, so I wondered why…”. Everybody sees everything.

Did you find that unbearable?

I didn’t like it.

One of your responses to it, as a child and adolescent, was to withdraw into silence…

Yes, I was acutely aware that I was shy. What is the thing about Robert? Robert is shy, it’s his defining characteristic. It started to feed into the gender thing. I thought that boys were supposed to be boisterous, to be cheeky and cajoling.

But at the same time you also wanted to perform from a very early age, didn’t you?

Yes, it was ever so important because, having said that I was shy, what I could do was do impressions of teachers. And I could make up silly songs. It really helped; I became less frightened, and it helped with having some friends. I was never bullied because I amused a little gang of boys.

So it was a kind of protection?

By the time I got to university it was so important I wore it like a suit of armour.

You’re fearless about revisiting your childhood diaries, however painful or mortifying they are…

Apart from the Mum entries about finding out that she was ill, there’s so much embarrassing stuff about fancying girls that I didn’t have to repeat anything. What I would say to that young man now would be: don’t worry, there really is a lot of time for this. It’s fine. Don’t worry about your virginity. Seventeen is not particularly old. And also, instead of blaming these girls for not fancying you, you know that school blazer you’ve been wearing five days a week for three summers? Why don’t you get that dry-cleaned, or ask Mum how to get it washed? Or why don’t you have a bath more than once or twice a week? Maybe pop a mint in your mouth after lunch. And maybe don’t wear a tie to parties.

You’re also very open about more recent times – finding fatherhood hard, drinking too much, and so on…

I drink a lot less than I used to, but I haven’t given up altogether. And I do a lot more work in the house than I used to, but it’s still not equal to Abbie’s contribution. I still get angry when actually I’m feeling embarrassed, or when I’m feeling anxiety or fear. I catch myself much more often. Abbie and I don’t have big rows any more because I’m being less of a dickhead. So it’s all going in the right direction, but I couldn’t possibly pretend that everything’s perfect now. I don’t think anyone would believe me.

You suffered a huge loss with the premature death of your mother, but you also explore your fractured relationship with your father…

It was always going to be a bit of a struggle. And I wouldn’t say we got there but there were moments where we were definitely on the same team. And he was just always on your side. You were his son, and that was that.

And what was it like to write about your mum?

I was spending time with her again. This might sound ghoulish but you’re sort of reanimating these characters from your life. You’re turning a person into a character, but there she is, walking around and talking.

You portray yourself as a young man desperate for fame. Do you feel, now, that you’re famous enough?

Yes I do. I really do. I’m not going to grumble about it but it does come with some downsides, not least what it does to your head. It’s not normal to walk down the street and have people randomly grin at you.

They might grin again once your new project with David Mitchell hits the screens. What’s it about?

It’s called Back. I love my new character, who’s nothing like Jeremy [from Peep Show], so that’s enjoyable, because Andrew is clever, charming, and probably a needy people-pleaser, possibly with a huge streak of malice, who comes back into David’s life potentially just to make him incredibly miserable, and David’s very good at playing miserable.

Anything else on the horizon?

I’m going to write a novel. It’s two paragraphs long. So there’s an idea. A good idea.

Interview by Alex Clark

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion