J.D. Vance’s bestselling 2016 memoir, Hillbilly Elegy, is the story of his childhood in an Appalachian “hillbilly” family who migrated from Kentucky to an Ohio steel town. In Vance’s telling, family members struggle with underemployment, drug abuse, and domestic strife—but he manages to rise above, joining the Marines, getting a college degree, and ending up at Yale Law.

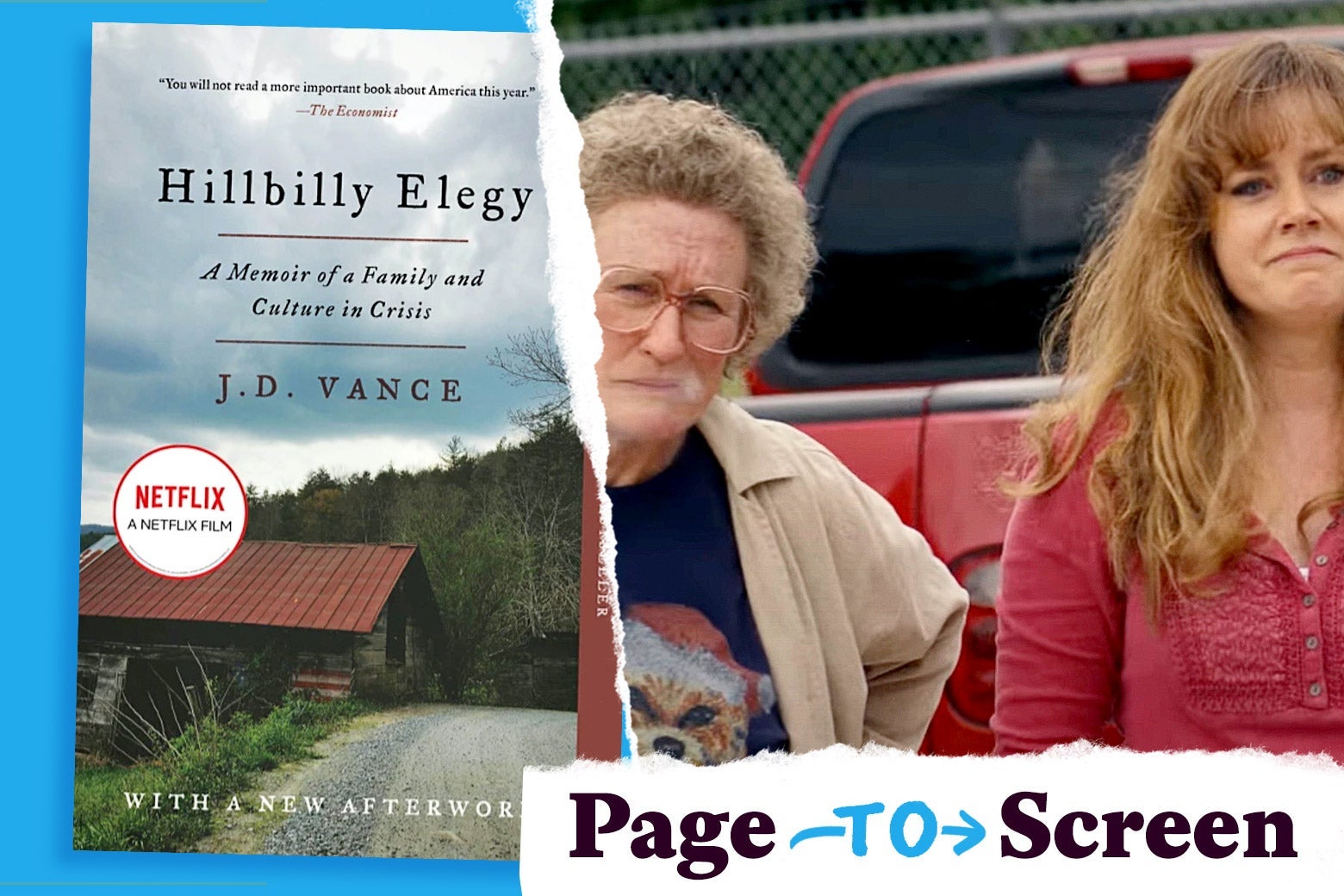

Director Ron Howard’s adaptation of this story, available to Netflix subscribers on Tuesday, comes complete with Glenn Close chewing the scenery as Vance’s grandmother Mamaw, and Amy Adams as his addict mother Bev. But in simplifying the story to a weepy family tale, the movie loses much of what made Hillbilly Elegy so compelling—and controversial. We rounded up the most significant changes that Howard and screenwriter Vanessa Taylor made, below.

Genre

Hillbilly Elegy, the book, is a memoir, sure, with all the fuzziness of fact and fiction that that entails. But Vance’s memories come mixed with stretches of analysis of “hillbilly” social mores, sociological studies, and historical texts. The book contains footnotes to such work as Jack Temple Kirby’s article “The Southern Exodus, 1910-1960: A Primer for Historians,” Carl E. Feather’s book Mountain People in a Flat Land, and William Julius Wilson’s The Truly Disadvantaged. Vance also favorably cites Charles Murray’s book Losing Ground, calling it “seminal”—a warning sign to anyone familiar with Murray’s work, which argues that human intelligence is genetically determined and varies by race. Critics like Elizabeth Catte have pointed out how Vance cherry-picked his ideas from a century of Appalachian studies, applying theories of regional difference you might call outdated at best and derivative of eugenics at worst.

I wondered if the movie might try to do a little of this analytical work—by having Vance encounter some of these referenced histories and sociological studies in law school, perhaps. Nope! The film is all family story, no theories.

“Hillbilly” Culture

Do “hillbillies” “act that way” because of structural forces that have left their local economies barren of opportunity? Or are they making individual choices, and should therefore be responsible for the outcomes? These questions are the primary preoccupation of Vance’s memoir. Vance acknowledges that the closure of mines and factories has hurt Appalachia (and the Midwest, where many Appalachian families like his migrated over the course of the 20th century). But Vance argues that “his” people are reacting “to bad circumstances in the worst way possible,” manifesting “a willingness to blame everyone but yourself.” This reaction, he writes, “is distinct from the larger economic landscape of modern America”; people, in Vance’s cosmology, always have control over their responses, no matter how bad their circumstances.

The movie boils the state of the Rust Belt down to a few familiar visuals: a sequence showing his town’s formerly bustling steel factory, followed by one showing the factory shuttered; another with J.D., home from law school, driving down the streets of Middletown, seeing people hanging out in the middle of the day, shirtless and up to no good. There is a strong “coastal newspaper sends reporter to see how bad things are in Ohio” vibe to the way these problems are represented—every beat is familiar.

But the film also sidesteps some of Vance’s more politically incendiary passages about “personal responsibility.” As a teenager, Vance works at a local grocery store, a job that also appears in the film. In the memoir, he describes with resentment many members of the working class he observed “gaming the welfare system” and “living off the dole” while he put in the hours. “Every two weeks, I’d get a small paycheck and notice the line where federal and state income taxes were deducted from my wages,” he writes. “At least as often, our drug-addict neighbor would buy T-bone steaks, which I was too poor to buy for myself but was forced by Uncle Sam to buy for someone else.”

In the book, this is a moment of political awakening, Vance’s first indication that Mamaw’s beloved Democratic Party wasn’t so great. But you won’t find it in this movie. Nor will you find any other of Vance’s memoir’s bits of red meat for the red states. (“I’m the kind of patriot whom people on the Acela corridor laugh at,” he reflects elsewhere.) Ron Howard’s just not going there.

The Timeline

Screenwriter Taylor has taken a particular scene from Vance’s memoir—a fish-out-of-water dinner with law firms offering summer employment, complete with his confusion over varieties of forks and types of white wine—and turned it into a frame story which is then filled out with flashbacks. At the dinner, J.D. gets a phone call from his sister Lindsay, who announces their mother Bev has overdosed and needs to go back into rehab. The call prompts J.D. to return to Ohio to handle the situation and then sprint back to New Haven to make it to his final interview for a summer internship.

In Vance’s memoir, Bev did start doing heroin during J.D.’s time at law school, but there’s no single major crisis like the one in the movie. In fact, by the time J.D. arrives at Yale, he seems to have largely come to terms with leaving the place where he grew up. Instead, his biggest crisis over his responsibility to his family comes when J.D. decides to enlist in the Marines, taking his first step away from Middletown. Upon enlistment, he worries the most not about being “killed in Iraq, or that I’d fail to make the cut”—he worries about Mamaw. “Something inside me knew that she wouldn’t survive my time in the Marines,” he writes. And she doesn’t, dying of a lung infection a few years in.

Perhaps the film re-centers J.D’s moment of crisis around Bev’s drug use because this is a familiar plot in the pantheon of Appalachian stories—the family trying to figure out how to handle a loved one’s addiction.

Fried Bologna Sandwich

Some of the most interesting parts of the Vance memoir have to do with the way he imposes discipline upon himself, after he leaves Middletown. He goes into the Marines, he writes, and he learns—how to balance a checkbook, keep a schedule, study, and plan. In the Marines, at Ohio State, and at Yale, he’s remaking himself. “I felt completely in control of my destiny in a way that I never had before,” he writes of his time at Ohio State, where he pays his own bills and gets straight A’s.

In the Marines, he also learns a different way to eat. “I began asking questions I’d never asked before: Is there added sugar? Does this meat have a lot of saturated fat? How much salt?” he writes. The food he ate at Mamaw’s, where “everything was fried,” has “lost its luster.” This is what’s interesting about Hillbilly Elegy, the memoir: It’s written by a person with contempt for those “Acela elites,” but also a person who, on some levels, has to hand it to those “elites” and their way of life. Elsewhere in the book, Vance writes of working-class white resentment of Michelle Obama: “[She] tells us we shouldn’t be feeding our children certain foods, and we hate her for it—not because we think she’s wrong but because we know she’s right.” Vance has climbed the ladder, marrying a Yale Law classmate who came from an upper-middle-class background, and having seen what he’s seen, he’s not going back.

The movie can’t handle this kind of ambiguity. J.D. goes to a birthday party at Lindsay’s house, and Lindsay brings him a fried bologna sandwich. “Bet they don’t have that at Yale,” she says. “I think this might be illegal at Yale,” he replies, eating it happily.

The Terminator

J.D. and Mamaw both love the movie Terminator 2. In the book, Vance remembers having a feeling, throughout childhood and adolescence, of being “either chased by the bad terminator, or protected by the bad one.” He describes Mamaw as “my keeper, my protector, and if need be, my own goddamned terminator.”

The “neutral Terminator” mentioned by Mamaw in the movie does not exist in the memoir, nor in the Terminator universe.