Suharto’s mate: how a little-known Australian became a secret go-between for Indonesia’s leader and the West

- Clive Williams’ role as an unofficial broker in Indonesia’s ties with foreign governments was ‘very much obscured and underrated’, biographer says

- His discretion and unobtrusive nature earned him the trust of Suharto, who treated him as a ‘family friend’, a new biography reveals

“Clive’s role in history has been very much obscured and underrated all this time,” said Shannon Smith, author of the first-ever biography of Williams, Occidental Preacher, Accidental Teacher: The Enigmatic Clive Williams.

“Though he was referred to by name in the cables that the US embassy in Jakarta sent to Washington, Australian top diplomats concealed his identity by using a special code when discussing him.”

Army general Suharto first took control of the country in 1966, following a failed coup that he blamed on the communists. In 1967, he was named acting president before being appointed to office the following year. He went on to govern the archipelagic nation with an iron fist until he was toppled by a protest movement in 1998.

Smith said there was no doubt as to Williams’ role as a “backchannel”.

“In the 1970s, Clive was the important go-between for Jakarta and Canberra in the lead-up to Indonesia’s invasion of East Timor and its aftermath,” Smith said, adding that Williams’ services would be called upon again when relations between the neighbouring countries reached a nadir following the Santa Cruz massacre on November 12, 1991.

East Timor has Indonesia’s backing, but can it meet the costs of being in Asean?

Historian Adrian Vickers at the University of Sydney said unofficial intermediaries or brokers had always played an important role in the history of contact between Indonesia and the rest of the world.

“There’s a long history of cultural brokers with the important language and cultural skills that officials often lack,” he said, adding that because they were “unofficial”, they afforded their masters the useful element of “deniability”.

“For as long as we have records, there have been traders, interpreters or people who just happened to be on the spot.”

Amsterdam-based historian Joss Wibisono agreed with Vickers, saying the most successful of these intermediaries “tended to be creatures who understood both worlds for which they acted as go-betweens”.

“Their role is to mitigate and prevent misunderstanding stemming from cultural and language barriers.”

In a strange bit of historical coincidence, Williams was born in Geelong, Victoria, the same town as George Ernest Morrison (1862-1920), who earned his place in history as a political adviser to Yuan Shikai, the first president of the Republic of China.

In Geelong, Morrison is fondly remembered for his important historical role as “our Chinese Morrison” or “Morrison of Peking”. But Williams, who was born one year after Morrison’s death, is little known in his hometown despite having played a similarly paramount role in connecting his country and other Western powers with Indonesia.

Smith said Williams took to that role superbly, thanks largely to having the necessary traits and disposition for the job.

“In many ways, he became the quintessential Javanese man: never boastful, unobtrusive, cognisant of the Indonesian social hierarchy and discreet to a fault,” he said, adding these qualities also enabled Williams to adapt to life in Indonesia, which became his home until his death in 2001 at the age of 80.

Why is a Singapore firm suing a dictator’s children over a theme park?

Williams’ entanglement with Indonesia started in a curious way.

Ship-bound for the newly independent Indonesia in 1950 as a “missionary” for the Jehovah’s Witnesses, Williams arrived in Manado, North Sulawesi, a predominantly Christian part of the country, to “spread the message”.

“The Jehovah’s Witnesses in his day were different from what they later became,” Smith said. “The movement in Australia was so anti-mainstream that it attracted minority subgroups. Clive, who converted at 16, was struggling with his sexuality at the time and must have found refuge in its discipline, sense of camaraderie and belonging.”

But in 1954, Williams was inexplicably expelled by the Jehovah’s Witnesses for “unchristian conduct”. Smith said the reason for his being “disfellowshipped” was never fully explained.

In the aftermath of his estrangement from the Witnesses, Williams moved to Semarang, Central Java, where he established himself as a successful chiropodist and English teacher.

After a bitter independence struggle against the Dutch, Indonesia declared English, rather than Dutch, as its main foreign language. The prominence of English in the nascent republic would prove to be life-changing for Williams.

He quickly built up a formidable clientele list as an English instructor, including a contract with the British American Tobacco company, as well as providing private lessons to wealthy Indonesians.

Through one of these students, Smith said, he was introduced to Siti Hartinah Suharto, better known as Tien Suharto, the wife of Colonel Suharto, who was commander of the 15th Infantry Regiment in Solo at the time.

“Tien became Clive’s student and soon her husband engaged him to provide English lessons to the troops of the Diponegoro Division under his command.”

In 1965, the fortunes of Lieutenant General Suharto, then Commander of the Army Strategic Reserve Units (Kostrad), were about to change forever.

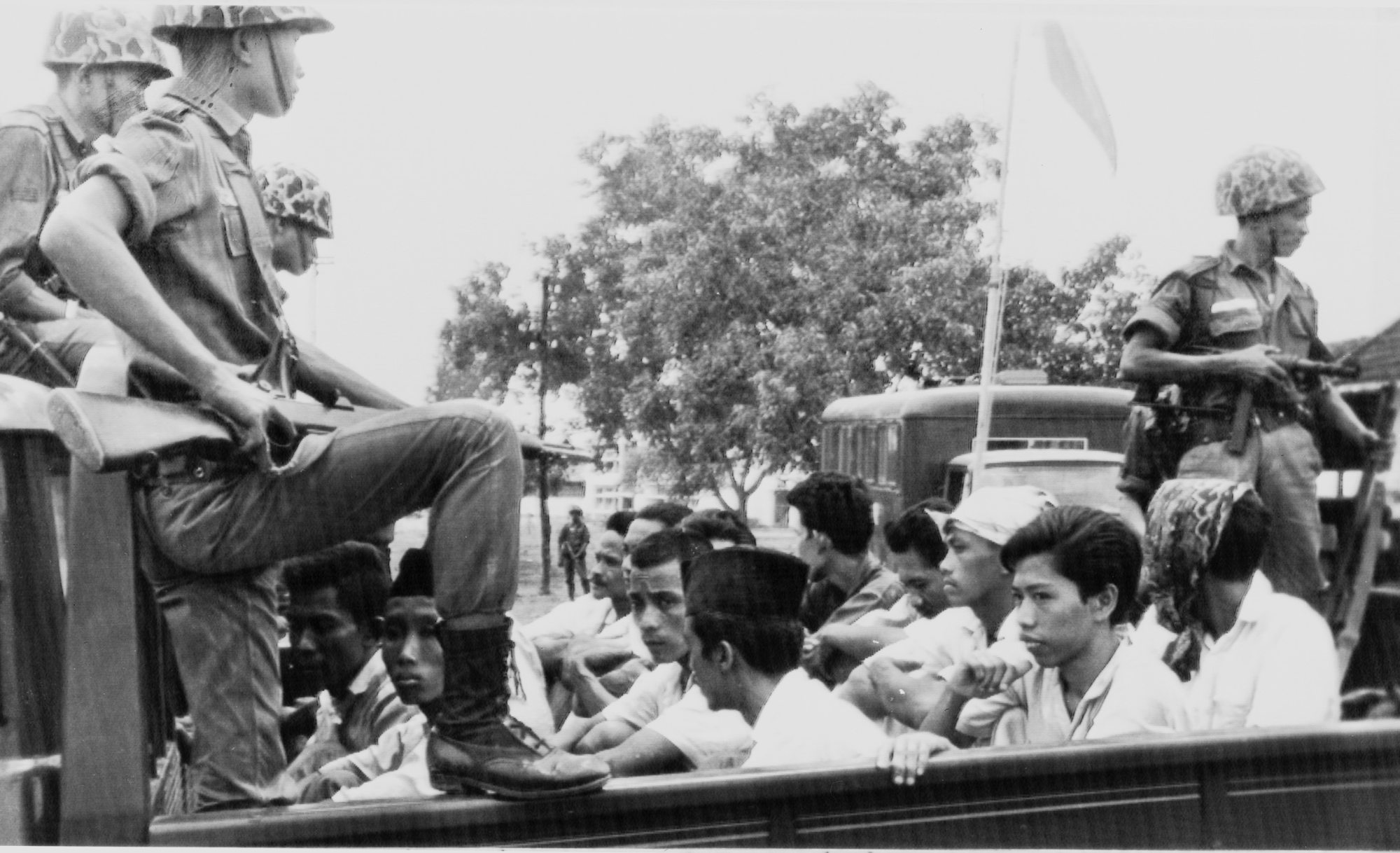

Following the attempted coup on September 30, in which six army generals were forcibly kidnapped and murdered by rogue soldiers, Suharto swiftly mobilised his troops and launched his own counter-revolution, directed at the communists.

Putting the blame for the botched coup squarely on the shoulders of the Indonesian Communist Party, Indonesia’s third-largest political party at the time, he proceeded to quash them in what would become a bloody anti-communist purge.

Between 500,000 and 1 million Indonesians accused of being communist sympathisers died in the 1965-1966 purge, largely through extrajudicial killings.

After Suharto became president, Williams moved to Jakarta. He was given a house in Jalan Waringin, Central Jakarta, by the president, who lived with his family on the street behind, Jalan Cendana.

Smith said Williams’ house in Jalan Waringin had a connecting back door leading to Suharto’s own residence, allowing him to “come and go as he pleased”.

Australian journalist Frank Palmos, who was posted to Jakarta in 1964 at the age of 24 as correspondent for the Melbourne and Sydney Herald Sun, said he interacted with Williams since he lived just “four doors away” on Jalan Rasamala.

“Clive’s success as a go-between [for the Suhartos] lay with the personal trust and friendship that grew from the early English lessons days,” Palmos said.

Williams’ status as Suharto’s trusted friend was also known to foreign journalists in Jakarta, Palmos added.

“Clive had [many] taps on his door from hopeful Western correspondents who seemed always to fail but never give up trying to get an interview with this mysterious Clive who clearly had close dealings with the Suharto family.”

Smith pointed out Williams’ reticence with the “expat crowd” might have earned him greater trust with the Suhartos, who saw him as a “family friend” with whom they had “regular breakfasts”.

“Clive would remain intensely loyal to Suharto, his friend, till his death, never breathing a word about the nature of their association.”

Our father, the dictator: Suharto’s children hope to rehabilitate family name

Palmos noted that Williams, like Suharto, had mastered the art of being inscrutable and only revealed what he wanted to. He recalled his impression after a meeting with Williams at the latter’s residence.

“On reflection after hearing Clive’s quiet remarks, I walked back to Rasamala or Waringin’s busy neighbourhood no less enlightened yet pleased Clive and I had at least enjoyed tea and pastry.”

Williams, an enigma in life, continues to be shrouded in mystery even in death.

“We know Clive died in Indonesia, but we don’t know where he is buried. His lawyer refused to divulge the location of his final resting place,” Smith said.