Transcript

March 11, 2013

Russell L. Riley

Up and running. How do you prefer to be called?

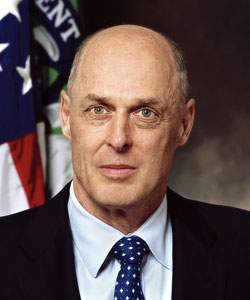

Henry M. Paulson Jr.

Hank.

Riley

All right, may we call you Hank?

Paulson

Absolutely.

Riley

Terrific. This is the Henry Paulson interview, and thank you for agreeing to be here as a part of the George W. Bush Oral History Project. We've just talked about the ground rules before the record began.

Paulson

Yes.

Riley

One thing we have to do as an administrative matter is I need to get everybody to go around the table and say a few words, identify yourself, so that the transcriber will know who is speaking. I'm Russell Riley, the chair of the Oral History Program.

Peter Rodriguez

I'm Peter Rodriguez. I'm a professor at the Darden School of Business.

Rebecca Neale

I'm Rebecca Neale. I'm Mr. Paulson's chief of staff.

Robert Strong

Bob Strong. I'm a politics professor at Washington and Lee University, currently the provost.

Barbara A. Perry

I'm Barbara Perry. I'm a senior fellow here at the Miller Center, in the Presidential Oral History Program.

Riley

All right. We talked on the phone.

Paulson

Right.

Riley

And I told you that we'll try to keep the preliminaries to a minimum, but because this is a Presidential Oral History Program, and you have some experience at the White House before you get to the George W. Bush Presidency, I hope you'll indulge a few questions about your experience with President [Richard M.] Nixon. Can you tell us about your time in the Nixon administration?

Paulson

Yes. I joined the administration in April of 1972, six weeks before the Watergate break-in. I had been part of a team at the Defense Department, a small group, an analysis group. As a matter of fact, Steve Hadley, who was George Bush's National Security Advisor, had been in the same group. John Spratt, who was Chairman of the House Budget Committee, and three other guys who eventually became CEOs [chief executive officers] served with me. It was a group of young people.

I had worked on the Lockheed rescue—It was actually my first bailout, believe it or not, and so I worked on that project. I got to know John Connally when he was Secretary of the Treasury. Walt Minnick, who was a good friend of mine from the Pentagon, had gone over, so I'd had a chance to go to the White House. I worked for a guy named Lewis Engman and after the 1972 election, he became Chairman of the Federal Trade Commission and I received, for a young guy, a big promotion. I became the Assistant Director of the Domestic Council and I was the liaison with Treasury, when George Shultz was at Treasury. Ken Dam, who later became Paul O'Neill's deputy, when Paul was Treasury Secretary, was an assistant to Secretary Shultz.

Watergate became a big political scandal hitting the White House. In February of '73, Mel Laird came over to replace John Ehrlichman and I wanted to resign then, but I had known Laird from the Defense Department, and he asked me to stay. I stayed through the end of the year, when I went to Goldman Sachs. Ken Cole was Laird's deputy; I worked closest with him. I had, I thought, a pretty good relationship with Richard Nixon for a young person; I got along pretty well with him.

Perry

What lessons did you learn?

Paulson

I learned some terrific lessons. I had come to the conclusion before I went there that almost as important as what you do is who you do it with. I had worked for four or five senior people in the Pentagon and I noticed that I worked better with—and learned more from—some more than others. I didn't know what the word "mentor" was, but some were really good mentors, and I seemed to need a mentor.

In interviewing for a job in the White House, I found a boss I respected and I was confident I could learn from. He was Lew Engman. Lew didn't have a great job to offer me. He had someone else who was doing the tax policy work and was the liaison with Treasury, and I was initially given a job that wasn't too interesting to me, but I could just tell I would get along very well with him. He's from Grand Rapids, Michigan, he'd worked for a small law firm, and when I got to the White House he told me immediately that everything I did not only had to be ethical to the highest degree, but I had to ask myself how would it appear if every memo I wrote, every conversation I had, was on the front page of the New York Times or Washington Post.

Then, when I was there a short time, I still remember a very vivid conversation. I remember John Ehrlichman telling me not to work with Chuck Colson or members of his staff. I said, "Why wouldn't I do that?" The way the White House was organized, Ehrlichman was the top Domestic Policy Advisor, Henry Kissinger was National Security Advisor and Chuck Colson was responsible for dealing with outside interest groups. And he said, "Well, the guy is highly political and short on principle," and I said, "Then what's he doing on Richard Nixon's staff?" He said, "Richard Nixon is a very complicated guy. Henry Kissinger appeals to the President's intellectual side, Len Garment (another senior advisor) represents Nixon's liberal dimension," you know on and on. Then he said, "He's never had an easy election and he's a bit paranoid. He believes the election was stolen from him in Cook County in'60, and in '68, if the campaign had gone another few days, he would have lost to [Hubert] Humphrey, so he wants to always have a derringer strapped to his ankle and that derringer is Chuck Colson." John Ehrlichman really knew how to turn a phrase.

REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT

I went to see Ehrlichman when [Harry Robbins] Haldeman's name was in the paper and said, "I don't know if he's innocent or guilty, but he's hurting the President and he should go." A week later, Ehrlichman's name was in the newspapers and he was gone shortly thereafter. I would say the only other thing I—Well, I'm not going to get into all my Richard Nixon stories; this is George Bush and we have a lot to cover.

Riley

Can I ask, just as a bridge, did that experience cause you to want to get out of politics?

Paulson

At the time, yes. But I always intended to leave government after a few years. I had been very interested in conservation and the environment, so it was just crazy the way some of these decisions were made. I had a conversation with the President about leaving and he said, "Is there anything that would keep you here?" I said, "Well, maybe if I could run the park service," and he said, "You should have asked me earlier, I gave that to Ron Walker." Well, Ron Walker was his advance man. I didn't think he knew a bird from a tree. Nixon asked if I would like to run the Fish and Game Department. I was 26 or 27 years old. I remember talking to a few people on the outside and they said, "Listen, if you go to the private sector now, they'll look at you as being a bright young guy who did some very interesting things in government. If you run the Fish and Game Department, they'll look at you the same way." I had very good opportunities to do a lot of different things, and I started at the bottom. I took the offer for the least amount of money and went somewhere where I would learn, while some of my friends who stayed in Washington, they just sort of bounced around. They were lobbyists, hoping to go back to another administration.

I had an opportunity to go back and work for Ronald Reagan, I think in '84, to be his Domestic Advisor. I had just become a partner at Goldman Sachs, so it didn't make sense for me to leave the private sector just as my career in investment banking was just beginning to take off. But no, what that White House experience did for me, being there, I had vivid memories of—There was a flip. Before Watergate, everything was energizing and fulfilling—and I say Watergate, Watergate being the time that Ehrlichman and Haldeman left and it all hit the fan. Before then, the power was in the White House, to the point of becoming almost embarrassing.

I was a kid and if George Shultz wanted to send a memo on tax reform or something to the White House, it would go to Ehrlichman, who would send it to me, I'd write a cover memo. The two of us would go in and talk to the President about it and no one from Treasury was even there. I always made sure that I just treated everyone at the Department of Treasury with the utmost respect. After Watergate, there was nothing done in the White House, literally I had nothing to do. The only work I had to do was the work that Shultz's staff let me do and kept me informed and treated me with respect so I have some pleasant memories of going across to the Treasury Department. Again, I really do not want to spend a lot of time doing this, because there's a lot of other things I want to cover.

Riley

Sure.

Paulson

I had been asked by the Bush administration several times to be Treasury Secretary, and I had turned them down. There was then a time, which I wrote about in my book, On the Brink, when I had agreed—Josh Bolten had persuaded me to have dinner with the President the night before Hu Jintao, the President of China, was to have a state lunch. I was asked to that lunch and so I was going to come in the night before and have dinner with the President. It finally dawned on me that I was not going to take the President's time and tell him no, and there's no way I was going to do this. So I called and canceled at the last minute.

So I showed up for this lunch and George Bush was polite but cool. [Richard B.] Cheney was cold too, and as I walked out of the East Wing—It was a beautiful spring day in April and there were cherry blossoms everywhere—I looked right across into Treasury and it evoked what it used to be like for me, walking out of that East Wing. I was very quiet, and Wendy [Paulson] said to me, "Are you sorry you turned it down?" I said, "Oh, don't worry about it," and she said, "Well, if you turned it down for me, Sweetie, I really didn't want you to do it—but if it was important enough to you, I would have accepted it."

When the White House unexpectedly came back to me again several weeks later—this time through James Baker, I accepted. Wendy was hurt and upset. I said, "I thought you had told me it was OK." So yes, I believe net-net, the Nixon White House was a positive experience for me. I really enjoyed my time down there, although it ended in an extraordinary and devastating way.

Riley

Sure. All right, Hank. When we talked on the phone, I said there would be a couple of preliminaries, and then you had indicated there were a lot of things you wanted to deal with, the first one being the financial crisis, right?

Paulson

Right.

Riley

Well, should I just open it up and let you tell us what you want to talk about?

Paulson

REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT

Riley

Are you comfortable with us injecting questions?

Paulson

Any way you want to do it. I'll maybe give you an outline and then I think you should inject questions as you go along.

Riley

OK.

Paulson

I think to understand this, I'll talk a little bit about my relationship with the President. I knew Dick Cheney because for whatever reason we'd met—I've even forgotten how and when we'd met—but he had asked me to come down and periodically brief him in the West Wing. So I would show up at the West Wing every, I don't know, four or five months. I'd tell him what I thought was happening in the economy and what was happening in China. Scooter [Irve Lewis, Jr.] Libby was his Chief of Staff and we would go in and we would talk, he'd ask questions. It was all one-sided. He was very friendly and nice, but I didn't ask him questions, I just did that and left.

Riley

Did he know markets well?

Paulson

He sure did. He and I had a good relationship. When I was at Treasury, we had different views on some issues, but he was smart as a whip and he understood what was going on in the financial crisis. He never once was one of these Republicans who said, "no bailouts." As a matter of fact, he was very much the other way. But I didn't know George Bush, and I had concerns about working for him based upon what I'd read in the press, based upon Iraq, based upon where he was on environmental issues, based upon my family's view of him. I would meet him when we'd go to the Kennedy Center Honors or attend some event in the White House, or if I got asked to a lunch or a dinner in the White House, but I didn't really know him, and I had not known Josh Bolten well.

Josh had been at Goldman Sachs, and had responsibility for regulatory relations in Europe. If I had met him, I didn't remember it. He was supposed to move to New York and be in the executive offices, but at the last minute he had decided to go to work for the Bush campaign in Austin, Texas. When he was in the West Wing, I had developed a bit of a relationship with him. REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT

REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT

In any event, if I had really understood how much a Treasury Secretary can accomplish every day and what a pleasure it would be to work for George Bush and with many of my colleagues at Treasury and the White House, I would have wanted to become Treasury Secretary and I would have accepted right away—and it wouldn't have been as good for me, because the fact that I initially had declined put me in a better bargaining position in terms of what I was able to ask for and get.

When Jim Baker was persuading me to accept the offer to be Treasury Secretary, he had given me advice. He said it's important to be the primary advisor and spokesman in all domestic and international economic issues. But I knew how powerful the White House was when I was there and that this White House was reputed to be the same REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT

So I had this list of requests. I wanted to not only have regular and easy access to the President, but I wanted to have the option to replace all of the political appointees at Treasury with people of my choosing, regardless of what party they were from. I didn't want to engage in political activities. I didn't want to have anything to do with any political campaign. I wanted to chair the weekly National Economic Council meetings, and I asked to have the meetings at Treasury and to have the pen and write the memos that went to the President on issues which were important to the Treasury Department. They agreed to all those things.

We had the first NEC [National Economic Council] lunch over at Treasury and then I realized it was totally inappropriate, because the Vice President attended, so I quickly suggested future meetings be held in the White House. These meetings were so informal with open and direct communication that the "chair" title proved to be meaningless. I found it was better to be coordinated than to have to do the coordinating yourself, so I quickly decided, unless it was something I really cared about, I didn't want our guys writing the memos.

One thing I did very well—I had spent 30 years working with CEOs and clients, and even when I ran Goldman Sachs, I advised a number of clients. So I was accustomed to giving advice to principals, where they were the decision maker. At Goldman Sachs, I had always said, "I don't care how smart you are, if you can't persuade a client, your idea is worthless." So I knew how to work with principals. Also, Goldman Sachs was a partnership, and I couldn't just order people around. I had many people at Goldman Sachs who thought they were smarter than I was, and a number of them were right, so I learned to persuade them rather than order if I wanted them to stay. It takes a very similar skill set to succeed in business as in Washington. It's just much more difficult in Washington, much, much more difficult, and so it takes a different mindset.

If you're Treasury Secretary, you can't be king. You can't do anything in Congress without persuading them. Regulators are independent; you have to persuade them. You have no power unless the President gives you power, so I knew when I went down to Washington that the agreement I worked out beforehand with President Bush was totally meaningless if I didn't develop a relationship with the President. And, if I didn't have a good working relationship with my boss, I would fail and that failure would be on me and not him.

[interruption]

Paulson

So if I didn't develop a relationship with the President, it wouldn't work. It would be my fault and not his. I had a year, basically, before the financial crisis hit, and if I hadn't had that year to develop that relationship with George Bush and with Ben Bernanke and Tim Geithner and all my other counterparts, it would have been a much different outcome.

The next point I would make is that when George Bush and I had the meeting in his office in the residence on the Saturday, which I wrote about in On the Brink, he talked about having me put together banking sanctions on Iran and North Korea. I told him that I also wanted to take charge of organizing the relationship with China. We talked about entitlements reform, which was to be a big, big thing.

When I was confirmed—and it seemed like an eternity, although it was I think record time and unanimous, but if it's happening to you—When the White House announces the intent to nominate before Congress has reviewed your taxes and done all the investigations, it was—I remember saying afterward, if I had understood that process, I might not have said yes, so I'm glad I didn't understand it.

Strong

People say in the American system, you're innocent until appointed.

Paulson

That's right. It just seemed like it lasted—When someone told me this is the fastest in modern times anybody has been approved, I said, "My God, that is hard to believe." So the President was getting his economic team together, and I wrote about that in On the Brink so I won't spend a lot of time on it. But when he got his economic team together at Camp David, the White House asked me if I would speak on entitlements reform and I said, "I would prefer to speak on financial crises. I think there's a lot of excesses in the system. We haven't had one in a while." You have financial market disruptions every eight to ten years—of course, not this huge thing we experienced. So I prepared material to talk about all the money sloshing around in the system, the hedge funds, and over-the-counter derivatives, the high levels of embedded leverage, the excesses.

I remember at the time being very impressed by the level of the President's questions—you could tell he'd gone to business school; he'd been in business. He asked the right things. He asked me a number of questions about over-the-counter derivatives, and I think he was surprised to understand the extent of the problem as I laid it out. He then asked what would cause a crisis, and I said I had no idea but, after the fact, it would be very obvious and a number of people would take credit for predicting it, but they would be unable to get the next one right. I said I didn't foresee the Russian default or the Asian financial crisis, but the key thing was to be prepared for it. That was July of 2006.

Riley

Hank, when you said to be prepared for it, did you mean that there needed to be some steps proactively taken?

Paulson

Yes, some steps proactively taken, which was where I was going to go.

Riley

OK, thank you.

Paulson

I had known Tim Geithner when he became president of the New York Fed [Federal Reserve Bank of New York] and I was at Goldman Sachs. We worked on this problem of the over-the-counter derivatives, where there was no transparency, there was no public market. It was six months, sometimes, before these trades were even documented, because they were entered into over the phone. It was a very hard thing to clean up, because one firm couldn't do it unilaterally. You couldn't move any faster than your counterparties moved. No one seemed to have the authority to deal with it.

Tim had been working on this issue in a highly professional way, so when I was nominated as Treasury Secretary, I tried to persuade Tim that he should be my deputy. He very nicely explained to me that he thought he could be more helpful where he was, and he actually was. I sought Tim's advice on how best to prepare and he told me about the President's Working Group on Financial Markets, which was chaired by the Treasury Secretary, and suggested that I use this as a vehicle to coordinate with the other regulators, including the Fed, the OCC [Office of the Comptroller of the Currency], the SEC [Securities and Exchange Commission], and the CFTC [Commodity Futures Trading Commission]. The New York Fed hadn't been a member of the President's Working Group on Financial Markets, so I then made Tim a member. He said, "You can just use it and run it like your own committee." And even though they're independent regulators, I pretty much ran it like the management committee at Goldman Sachs. I didn't give direct orders, but for the first time we scheduled meetings a year in advance, we had really detailed agendas, and we started focusing right away on preparing for a financial crisis.

Now, we weren't looking at mortgages, which I will get into in a minute. We were looking at hedge funds, and so we focused on their intersection with the major banks, and the risk that this posed for the major banks. We worked on over-the-counter derivatives. This group and its agenda helped us develop very good working relationships.

I also brought in a number of people from the outside government to work with me at Treasury, one of whom is a guy who is now the deputy mayor for Mayor [Michael] Bloomberg, Bob Steel, who is chairman of the board of Duke [University] and Aspen [Institute]. He had been a vice chairman at Goldman Sachs, had left like three or four years earlier. Bob understood markets. But the reason I picked him wasn't because he understood markets. He is one of the best people-persons I know. People loved working with him and he could work with anybody and get results.

One of the key things we had going for us during the crisis was that Ben Bernanke, Tim Geithner, and I had skills that complemented each other, and we liked and trusted each other, and that's important. Tim had explained to me that he worked with [Robert E.] Rubin and [Lawrence] Summers and [Alan] Greenspan and a bunch of other people who also worked well together, but the level of trust and organizational harmony we had was unique.

Rodriguez

Could you tell us where that came from? You were relatively new to Bernanke at least, I would suggest. Was that just an instant rapport or something like that?

Paulson

I'll get to that in a minute. Let me just finish this point first. Bob Steel did a superb job of working with the key staff members at the SEC, at the New York Fed, and at the Washington Fed, and the FDIC [Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation], which clearly helped bridge institutional differences and build cohesion.

Now, where did the trust come from? It's always hard to tell. I think first of all, I'm very good at developing trust. I have worked with a lot of different clients. I think Ben and Tim are also good at developing trust—and our skill sets complemented each other. I had working experience in the financial markets and in various countries around the world. Tim was really smart and had worked at Treasury and knew how government worked. He'd worked with Rubin at Treasury, been Under Secretary [of the Treasury] for International Affairs during the Asian financial crisis, so he just gave me a lot of help. The first economic speech I gave, I had Tim Geithner reviewing drafts and giving me comments. I didn't look at organizational boundaries; I'm not a great respecter of organizational structure. Ben is so smart and he's a superb economist and I'm not one, so I asked him a lot of questions. He had studied the Great Depression as a scholar and he was able to put that to great practical use. For whatever reason, it worked, and so we had our meetings with the President's Working Group, preparing for a crisis.

I'll say something about mortgages. None of the three of us—including most people at the time—saw the financial crisis coming through the mortgage route. Goldman Sachs had a mortgage unit, but at that time it wasn't a very important part of the business, and residential mortgages and subprime mortgages certainly weren't. I didn't know much about them, I didn't know much about that bubble when I was at Goldman, but when I got to Washington, as the subprime market heated up by the end of 2006, early the next year, we knew it, but didn't see it as posing a big threat to the US economy. Why? Because the subprime market in and of itself wasn't big enough to threaten the US economy and we didn't foresee the extent of the problem in the broader mortgage and housing market.

Since World War II the US had never experienced a national decline in housing prices. So when we had mortgage crises, they were on the commercial mortgage side, with commercial real estate, office buildings and so on, and that's what you had in the S&L [savings and loan] crisis. But there had never been a nationwide decline in housing prices.

Why? Because flawed government policies were very much at the root of a lot of this. The government subsidized home ownership through multiple programs ranging from Fannie [Mae] and Freddie [Mac] to the mortgage interest rate deduction, to the FHA [Federal Housing Administration] programs. In recent history going all the way back to World War II, housing prices just didn't fall nationally. If you bought a diversified pool of residential mortgages, the biggest risk you had was you would get your money back too soon, because when interest rates dropped, people prepaid their mortgage and you ended up with your money back and you had to reinvest it at a lower interest rate. That's what you were worried about, getting your money too soon. So the models, which were based on the last 60 years, didn't factor in a decline in home prices.

Nonetheless, another thing I had started focusing on in the early days—Two other things that sound prescient, but I didn't do them because I saw a crisis coming—I started working on Fannie and Freddie reform legislation right away. The reason I did was that at Goldman Sachs, I'd watched Fannie or Freddie—I hadn't thought a lot about them from a public policy standpoint, but they just struck me as being out of control, that they were so large. I remember saying, "The elephant is too big for the tent," because what I focused on was this: The way they made a lot of their money was taking the implicit federal guarantee and then buying in their own securities and holding them in their inventory. To do that, you have—and I don't want to get into technical stuff here, it's not going to be that helpful, but do you all know what duration risk is?

Rodriguez

Yes, they do.

Paulson

You know what duration risk is. Duration risk is you need a hedge, so you don't have exposure to interest rates moving up and down. And of course if you have a mortgage, even if it's a 30-year mortgage, the duration is going to be, I don't know, five or six years or whatever, because you get prepayments on interest, so you have to hedge. There would be some days when rates moved like ten basis points in a day and you'd find out that either Fannie or Freddie had a duration mismatch and they'd come in and quickly try to get things in order. I referred to them as the civil service of hedge funds, because if you're a hedge fund, you were worried about that all night and so on, but these guys would wake up, come into the office at 9:00 in the morning, "Oh, my God," and they'd start working and they were just so huge they disrupted the markets.

As I got into this when I got down there, what I found was what you typically find in Washington: there is a holy war. The Republicans, and Richard Shelby, the Chairman of the Senate Banking Committee, was the leader on this, basically said this is a bad construct, they're dangerous, they have all kinds of major risks associated with them and we want to drive them into the Potomac. They had a piece of legislation that was really good; it was actually the way I would have drafted the legislation. The Democrats, on the other hand, were in a different place. Now, both the Republicans and the Democrats, let me tell you, created and fed this beast, so the idea that the Democrats are the ones to blame is a bunch of hooey. But the legislation was going nowhere. There was no middle ground and I looked at it and I said that's just absurd. We're going to leave here and nothing's going to be done, and why wouldn't you want half a loaf rather than no loaf?

I wanted to negotiate with Barney Frank. I could not have had a more negative view of anybody from just what I'd read, so it seemed impossible. Bob Steel went up and developed a good relationship. Bob convinced me, based on recommendations he had received from Barney's staff, that I should spend some time with Barney, so I went up, and lo and behold, I really liked the guy, and then I learned that his reputation was one that you could trust him. You know, when he said something, he meant it. And Barney Frank ended up being right there with Judd Gregg, probably the closest professional relationship I developed when I was up at the Hill. I became a friend and admirer of his, and we worked together exceptionally well, particularly when we collaborated on legislation to stabilize the capital markets and prevent an economic catastrophe.

Then—as I wrote about, so I won't spend much time on it, I'll just note it; this was the first real problem I'd had with the White House staff. Basically, my relationship was very good, very smooth. Al Hubbard—who knows whether I would have been Treasury Secretary if Al Hubbard hadn't agreed to all the requests I made, some of which were unreasonable requests. I was just concerned with everything I'd heard about the White House. I'd had two or three people who worked in the administration tell me I was crazy to go there. REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT. So I just had an abundance of caution.

I said I was prepared to negotiate and find middle ground to reform the GSEs [government-sponsored enterprises], Fannie and Freddie, and I was prepared to give up a fair number of provisions in the Shelby plan if we could constrain the securities that they put in their inventories, and if we could get a real regulator with the normal powers that safety and soundness financial institution regulators have to make judgments about capital adequacy, because their capital was razor thin, and was defined by Congress and the regulator had no power to do anything other than accept the legislatively proscribed capital rules, inadequate though they were. There was no judgment associated with capital structure, it was formulaic, intangibles were even counted as capital. If you had come from the industry I had come from, you looked at it and it was beyond absurd. Now, maybe it made sense when they were set up initially, when they were just tiny little things or whatever.

So I had this principals meeting in the Roosevelt Room of the White House where all of the President's other economic, legislative, legal, and political advisors were sitting around the table, and literally every single person disagreed with my plan to reach a compromise with Barney Frank, the Ranking Member of the House Financial Services Committee. Harriet Miers, who was a general counsel at the time and who I thought was terrific on many things—you know she was the one who found my general counsel for me, gave me a guy, Bob Hoyt, who was superb, who was on her team, did all kinds of things to help me coming in—but she was just adamantly opposed to any compromise: This is what we've said, this is what the President said on this, this is what we've all said. I finally just had had it and said, "I disagree with all of you and I'm going to go to the President," and I wrote a memo.

Karl Rove was very helpful to me. We disagreed on some things, but he was as capable and professional as anyone I'd ever worked with: he understood policy, he understood politics, he was articulate. Karl did not favor my plan; he opposed it. So I wrote a memo, and the memo basically said this is where you all have been wrong on all these different things. I was very straightforward.

He called me over the Thanksgiving weekend and said, "Listen, take my advice and rewrite this memo. This is a foregone conclusion; you're going to win this. The reason has nothing to do with the merit. George Bush isn't going to go against his brand-new Secretary on the first thing you go to him with, so you've given the President no choice; he'll decide to do what you want to do. But please write the memo in a respectful way," and he had some very good suggestions as to how the world had changed and the Democrats were probably going to win the House, et cetera, et cetera.

So I wrote the memo the way he had suggested. I met with the President the Sunday after Thanksgiving—and if we have some time maybe at the very end of all of this, this was on Iraq, and he had had the National Security Council together in the Residence to talk about Iraq strategy. After that meeting, he gave me the memo back and said, "That's why I brought you down here, to make decisions like this. Go work with Barney." To make a very long story short, Barney and I had reached an agreement early on, well before Thanksgiving and the election, that if I was working with him in good faith, which I had been doing—I didn't have the permission yet from the White House to cut a deal, but I'd been up there negotiating and I told him what I wanted to do—that if after the election he was committee chair, he would stick with the deal, which he did.

Then after the midterm election, when the Democrats took control of the House of Representatives and Barney Frank became Chair of the House Financial Services Committee, the House passed our compromise bill to reform Fannie and Freddie and the Senate didn't do anything because Shelby didn't want to move it, and because [Christopher] Dodd, the Senate Banking Committee Chair, ran in Presidential primaries for a year, which also hindered us. Dodd essentially went to Iowa to focus on the upcoming caucus. But that early work with Barney Frank helped us build a relationship of trust, which proved to be critical to what we did later.

Rodriguez

Hank, can I ask a question? It sounds like you had identified in some ways the real vulnerabilities that were going on, the explosive rise in the repo [repurchase agreement] market, over-the-counter derivatives, problems with mortgages. No one knew the trigger, but it sounds like, early on, you had a sense of the big vulnerabilities. Do you ever wonder, or did anyone think at the time, or maybe during the crisis, that had we been able to achieve one of these early wins, perhaps some reform there, there would have been more substantial early—that it would have delayed or given more time?

Paulson

You know, it's funny. I've thought about that a lot and I'll give you another vulnerability I discovered and started working on right away too, but no. The excesses were already in the system because the credit bubble had been building for years, as had the housing bubble, and many of the worst mortgages were originated at the state level, under very inadequate state regulation, particularly in California and Florida. Even if we had been omniscient, the horse was already out of the barn; and as we will get to, we didn't have the authorities we needed to prevent the failure of nonbanks. And we couldn't have got the necessary authorities from Congress any earlier. Despite the fact that we started working on GSE reform in the fall of 2006, it took their near failure in June of 2008 to get the legislation we needed to stabilize them. And even in the darkest days of the crisis, after the Lehman [Brothers] failure, the House voted down the TARP [Troubled Assets Recovery Program] the first time. Beginning in 2007, I jawboned the banks publicly and privately to raise capital, but with only limited success because they viewed capital raising as a sign of economic weakness and vulnerability and came with a stigma because only the weakest banks were forced to raise capital to stave off failure, as Merrill Lynch, Citibank, and Morgan Stanley had done in late 2007.

If you look at the ten years before the crisis, '97 to 2007, the bubble years, median household income was flat, while household borrowing doubled. People were borrowing much more than they could sustain to maintain a standard of living they couldn't afford.

Every financial crisis from the beginning of time was created by flawed government policies. Banks always make a lot of mistakes, so the banks always get the blame, which is fine. Blame the banks. But what isn't fine is if you don't deal with the problems that got you there. The problem that got us there is we as a country and as a people borrow too much, save too little, and the incentives for doing that are built in our tax systems, et cetera. The fact was there were a number of flaws in our economic system and other governmental policies and programs. The biggest vulnerability I recognized early on—and I just hadn't been onto that when I was at Goldman Sachs—was the whole financial regulatory system.

Rodriguez

Do you mean the repo market and the OTCs [over-the-counter derivatives] not being regulated?

Paulson

That's one thing. I don't want to talk all day about the repo market, but in the repo market there's a huge problem that still hasn't gotten a lot of attention and it really fell outside of the regulatory system altogether, and it was really quite antiquated. BONY [Bank of New York] and J.P. Morgan administered the triparty repo system, but they really had no economic incentive to invest in it—to upgrade the technology—and they were doing this almost as a service. The government really didn't have oversight, and the practices were sloppy and it was a huge problem.

Now I was going to go to something much more basic: the architecture of our regulatory system. The structure was incredibly flawed and still is. We had five safety and soundness regulators, and financial institutions could often essentially pick their regulator. The Office of Thrift Supervision, which was at Treasury and very independent, was incompetent and AIG [American International Group, Inc.], GE [General Electric], IndyMac [Mortgage Services], Countrywide [Mortgage Organization], and WaMu [Washington Mutual], all were regulated by OTS [Office of Thrift Supervision]. Moreover, although there were emergency powers to prevent bankruptcies and disorderly failures of banks, no such authorities existed for failing nonbanks.

The cash markets were and still are regulated by one regulator, the SEC, the noncash markets, the futures or derivative markets, by another regulator, CFTC. The system essentially hadn't changed since the Great Depression, and the markets had grown dramatically. You don't have a problem if someone's got a bad idea, because it doesn't go anywhere. But securitization was a good idea, derivatives are a good idea, and they had grown so fast that the regulation and the system hadn't kept up with them. So good ideas created a huge problem within a flawed structure.

I don't remember exactly when it was, it was either the end of 2006 or beginning of 2007, but it was well before the financial crisis first manifested itself—I had persuaded David Nason to stay at Treasury, had promoted him to be an Assistant Secretary. He had worked with Bob Steel and with me, doing a study that we called "The Regulatory Blueprint." We basically said our regulatory system is all screwed up, here is our recommendation. That was published—roughly five years ago, on March 30th, a few weeks after Bear Stearns failed—this huge report, over a hundred pages, laying out the flaws in the regulatory system and making recommendations to fix it.

Again, that was another of the very rare instances when I had a problem with the White House staff. A number of my colleagues in the White House insisted we go to the President, because the Office of Management and Budget signs off on something like the Treasury's regulatory blueprint. Jim Nussle, the director of OMB, who is a very good guy, didn't like a number of the ideas we had and they also didn't like it just as a matter of policy process. How could Treasury put this out? I took the view that it wasn't going to be legislation, this is just our blueprint that we wanted to put out there for people to work from, and if OMB wanted to put one out, they should put one out. If Congress wanted to put one out, they would legislate. This was Treasury. But my White House colleagues said, "That's not the way it works in the administration."

We went to President Bush and he just basically said if any of you guys know as much about this topic as Hank Paulson, raise your hand. Otherwise, he's putting it out. And so we put it out there, and as Barney Frank writes in the foreword to the paperback edition of my book on the financial crisis, On the Brink, a number of those ideas were adopted in the Dodd/Frank regulatory reform legislation bill. I believe it was a very good piece of work.

But to get back to your question, I believe—and I'll say this now and then I'll say it at the end—I can be very hard on us for a lot of little mistakes, but the big things we did, we got right. I was as concerned as anybody down there about the crisis and I underestimated what we were dealing with every step of the way, right until we got the final authorities from Congress. But if I had been omniscient, there was not much I could have done that would have made a significant difference, because we couldn't have gotten the necessary powers to stem a once-in-75 year crisis a day earlier than we got them, and we didn't have the power to deal with a failing investment bank, or to fix Fannie or Freddie, or to recapitalize a highly leveraged banking system. The excesses were already in the system. There was a bubble; but of course, by definition the extent of the bubble is not fully understood until it bursts.

I made public remarks in June, and then a speech in July of 2008, saying that we needed resolution authorities to wind down a failing nonbank financial institution. I went up to the Hill with Ben Bernanke and told Barney Frank if Lehman goes, we have no way of handling this unless there is a private sector buyer, as there was for Bear Stearns. And Barney Frank said there's no way you can get these resolution authorities, emergency authorities, unless you stand up and say Lehman's going to go. And when it fails they will damage our economy. And of course Lehman would have gone the next day if we'd done that. It took [Barack] Obama many months, even after the crisis, to get this resolution authority for failing nonbanks. I mean, these are contentious issues.

Let me go through the crisis, sort of go through the outline very quickly. REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT

Riley

That's fine.

Paulson

I consider President George W. Bush a friend and I like and respect him immensely. That last weekend at Camp David, President and Laura Bush had Wendy and me and Condi there with the Bush family. I had a relationship with him the last year and a half, where I would have breakfasts and lunches alone, where we talked about a whole variety of things, where I gave advice on a whole variety of things and received advice and direction from him.

I'm very straightforward, so sometimes clients had a hard time initially, until they get used to me and know that I will always tell them exactly what I think in private, but there will never be any daylight between us publicly. I would say from Day One the President was terrific to me and I had my regular meetings. I quickly found out the normal private meetings really weren't private meetings, that private meetings just weren't Cabinet meetings. In the private meetings you'd have Dick Cheney and George Bush, and you would have Al Hubbard, and there'd be Josh and Joel Kaplan, who was absolutely fantastic and helped me all the way through the crisis, and two or three other people, and that was your private meeting.

Condi Rice said to me, "Hank, it's important to ask for and get regular private meetings over a meal." I had known Condi pretty well because, before the election, George Shultz sent her to see me. She basically said, "I'm a Russian expert. I didn't see the Russian default coming, because I don't understand economics. Can I go to work for Goldman Sachs and sit on your trading desk in London and/or New York?" I said, "I ran Goldman Sachs and I didn't see it coming, and people at our trading desk didn't see it coming, so don't think we can give you that kind of foresight—but yes, you can do that." She said, "Good, I'll get back to you in six months." And then in six months she called and said, "I'm going to join the Bush campaign." So she was unusually helpful to me and she told me, "Listen, just tell him you want to see him together and you want to see him alone."

The fact that Josh Bolten was White House Chief of Staff—Josh was a unique guy. I bet you there's never been a Chief of Staff like him. There's no ego there. All he did, he and Steve Hadley, the National Security Advisor, only supported the President. If I had been there with a different Chief of Staff, this thing might not have worked, but Josh encouraged me to spend time alone with the President and build a relationship. So when I said, "Hey, Josh, I don't like these big "private" meetings, how about me meeting with the President alone?" he began organizing them for me. Then I started having regular meetings either with the President alone or with the President and one other person—because I found it was sometimes better if you had someone else there who could remember what was going on and so on, so I'd ask for Josh or Joel to be there or whatever.

[Long redacted passage]

Paulson

OK, so the financial crisis. I've been through the regulatory blueprint. I've been through working with the President's Working Group. I was working very hard on the strategic dialogue with China, on free trade agreements, which I'll talk about later, on a whole series of things, while we were having the President's Working Group on Financial Markets do its work. I got deep into all this stuff. Although the markets looked frothy, I was starting to get even a little bit optimistic that maybe this crisis wouldn't come when I was in Washington, and I'd get out of Dodge before it came. Then, in July of 2007, it hit. I won't take you through all the different things—read On the Brink and you have it in terms of what happened.

What I would underscore was there clearly was a problem with mortgages. The President was away at his ranch in August and right up through Labor Day, so we worked around the clock at Treasury. Even though a lot of this should have come under HUD [Housing and Urban Development], we included the HUD Secretary, Alphonso Jackson, but I defined my job expansively, so Treasury did the work and came up with a series of initiatives that we thought would be important for the President to stand up and make an announcement right after he was back after Labor Day.

There was a bit of a hiccup with the White House staff, in that when Al Hubbard came back from vacation, it slowed us down. I would have done the same thing in his position; he wanted to understand it all. We were fortunate that during the financial crisis, we didn't have to spend hours talking with the White House staff and make sure everybody understood everything and take into account what their position was before we acted. But we did a lot of this before the President returned from his ranch. We announced two or three initiatives that we thought would be helpful.

Complexity was a huge problem. You had tranched mortgages; sometimes the most-risky pieces were put in tranches and they were very complex, and so rather than getting a mortgage from your neighborhood bank, these things were sliced and diced, put into packages, and sold to investors all around the world.

So how do you deal with minimizing defaults? You're always going to have six to seven hundred thousand defaults every year, because people's economic circumstances change and they can't afford to stay in their house. But when it makes sense, a bank will do a workout, and will let people stay in a house, because a default will be more costly to a bank. But the securities were so complex, the law was complex, the accounting was complex, lenders were spread out, investors all over the world. It turns out that if you had the most senior tranche, you might have one interest while someone who owns the riskiest tranche might have a different and conflicting interest, so how do you work your way through this?

Riley

And the ratings agencies were not helping on this.

Paulson

The rating agencies had given many of these complex mortgaged securities a AAA rating. They are sometimes cited as being the culprit. They're no more a culprit than many other market participants, because they used the same models, and the models just basically said you're not going to have a default. At the end I will tell you what I believe the flaws were in the system, and flawed government policies were the root causes of the crisis.

Riley

OK, great.

Paulson

The kinds of things we did early on were that we got a tax change through Congress that said if I reduce the principal on your mortgage, that's not a taxable gain to you. Otherwise, the guy has to pay a tax because debt forgiveness is a taxable event. And so we did that. If you are delinquent on your mortgage payment, if you get a warning letter from your bank, only 3 percent reply. People get scared and throw the notice away. If, on the other hand, you are contacted by a mortgage counselor, there's a much greater chance of responding. So we funded mortgage counselors and George Bush told everybody call this number, this is a hotline, and very famously, he was supposed to say 8-8-8 and he said 800, an 800 number, which was a Catholic charity, which was flooded by calls.

We did those things and we did a lot of others, and I did a lot of work with Sheila Bair at the FDIC on various programs on a voluntary basis to fast-track mortgage notifications, getting servicers and counselors and delinquent homeowners together to process mortgage workouts. We even had the SEC change accounting rules, and I described this as a Gordian knot, because it was just very hard to figure out how to untangle it, but we did a lot of work.

I was working with Ben Bernanke and Tim Geithner closely, meeting regularly. A lot of people think the crisis didn't start until Bear Stearns went under, but Bear Stearns went under almost ten months after the crisis began and the system was getting weaker and weaker and financial institutions increasingly stressed. Even more, you could just see how serious it was in Europe also. I knew the European banks had greater deficiencies than those in the US, although European regulators didn't recognize it, and so this thing just kept going on and on. We tried all sorts of private market solutions. I did a lot of work on something we called MLEC [Master Liquidity Enhancement Conduit], which was a private sector-generated vehicle, to try to provide liquidity in the securitization markets, because what happened was the mortgage problem was so concerning to people that pretty soon every complex financial instrument became illiquid. People became scared of mortgage securitizations.

Bob Steel, who worked with me, used a mad cow disease [bovine spongiform encephalopathy] analogy: it is not just a matter of price. You know, if there's a mad cow disease outbreak, you couldn't sell more hamburgers by simply reducing the price; people would stop buying beef, period. These complex securities were difficult to understand. There was no transparency, so they were all tainted in investors' eyes. They all became illiquid, so we worked very hard to find ways to bring price discovery and liquidity to the complex mortgage securitization market.

Things came to a head around mid-March, when Bear Stearns failed. I'm trying to hit the highlights, because on Bear Stearns you saw it; it's written about in On the Brink. But on a Thursday morning, Bob Steel came to see me and said that Rodgin Cohen, who was a Sullivan & Cromwell lawyer, had told him that Bear Stearns was having a liquidity issue.

I had learned how fast liquidity goes in an investment bank. Liquidity is really more important than capital. A liquidity cushion is essential. I had banks tell me all the time, we have a liquidity cushion and they didn't calculate liquidity the way we did at Goldman Sachs. The right way to view liquidity is assuming a worst-case scenario, where if everybody who can withdraw money does—and all those who can demand liquidity do—how much do you have left and how long does it last? Of course, under this scenario most institutions didn't have much excess liquidity. But most institutions' cushion calculations assumed their creditors would keep acting the way they had historically done under normal conditions. But this proved to be very wrong.

I thought that Bear was going to go quickly, and I was right. They called that night to say they were going to file for bankruptcy the next morning unless we assisted them. To make a long story short, we got very lucky and were able to save Bear Stearns because J.P. Morgan was a buyer and the New York Fed provided financial assistance. Although this was done with Fed authorities, I needed to be actively involved also because Ben Bernanke said early on, "Unless Treasury indemnifies us, I'm not going to make a loan." I said we'd indemnify the Fed because I figured we'd find a way to do it legally and I knew it would be horrific if Bear Stearns went down.

To step back even further, some people argue that the Bear Stearns rescue was a huge mistake. Some of the ideologues have said that we created a moral hazard, because the reason Lehman had the problem was that we said we'd bail out Bear Stearns. Quite the contrary. If Bear Stearns had gone, Lehman would have gone a few days later, and we weren't prepared. We hadn't even stabilized Fannie or Freddie, yet the market was so scared, Europeans were so scared, that even after rescuing Bear Stearns it took a lot of reassuring to convince the market that the other US investment banks were creditworthy. The other thing we learned was that a Fed loan, in and of itself, was insufficient to prevent the failure of an investment bank in the midst of a bank run. In a panic, customers, creditors, and counterparties don't stick around; they pull their money out and run.

After we announced the Fed loan to Bear Stearns through J.P. Morgan on a Friday, by the end of the day it was clear that Bear was going to fail by Monday unless we found a buyer. They had a capital shortfall problem and a liquidity problem. We were fortunate enough to find a buyer, because there was no legal authority for the Fed or any other government body to put capital in a nonbank and no authority to guarantee its liabilities. Our laws made no provision for emergency rescues or wind-downs of nonbanks. Fortunately we found a buyer in J.P. Morgan to provide the capital. J.P. Morgan not only had to agree to buy but had to agree to guarantee the trading book during the pendency of the shareholder vote, to prop Bear up while the merger was being completed. But we could only persuade J.P. Morgan to buy Bear if they received assistance from the government in the form of a nonrecourse loan against Bear's troubled mortgage portfolio. J.P. Morgan provided the permanent capital and a necessary guarantee to stop the panic, but the New York Fed needed to essentially make a nonrecourse loan secured by Bear's mortgage portfolio through an innovative use of their emergency lending powers.

Two other things happened here that were interesting. I had heard we didn't have authorities to deal with failing institutions that were not banks, but that didn't sound right to me. I just believed that there had to be some creative interpretation of some law we could use. I had been in England at the end of the year to visit Gordon Brown when he was Prime Minister and Alistair Darling was Chancellor, when Northern Rock was coming unglued. Gordon and Alistair asked if I would be on the stage with Alistair to divert some of the angst while he answered the questions about Northern Rock, and I agreed to do it. I saw how brutal the UK [United Kingdom] press was. He was arguing that the UK government didn't have the emergency powers they needed to deal with a failing savings bank like North Rock. Afterward, I said to my chief of staff, "What a bunch of bullshit," you know, "that her majesty's government doesn't have these powers somewhere. These guys are fumbling and bumbling." It turns out they didn't have the necessary powers and they did what they could. I tell this story because it helps me understand where the Lehman skeptics are coming from.

I assumed we could find some power we could creatively use, and on Sunday, my general counsel, Bob Hoyt, who was great through all of this, came back to me and said there were no powers for Treasury to have acted to save Bear or even to indemnify the Fed on their emergency loan as I had promised Ben and Tim. He had worked with the Justice Department, and undertaken an exhaustive review. So I had to call Ben and Tim and say there ain't no powers, and so I finally wrote an indemnification that I jokingly called the "all dollars are green" letter, saying that as Treasury Secretary, I recognize that if you guarantee this and lose money, we'll get less money in the Treasury. So, although we avoided disaster with Bear Stearns, we now recognized the extent of the vulnerability of Lehman Brothers, because Lehman had a weak balance sheet, was the next smallest investment bank, and was overexposed to real estate.

Sometime after the Bear failure, Ben Bernanke and I visited Barney Frank, who was the Chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, to tell him we needed some new emergency powers to wind down a failing investment bank outside of bankruptcy to protect our economy and we were worried that Lehman might be the next investment bank to fail.

Barney understood our problems, but said it would be impossible to get Congress to act unless we said Lehman is likely to fail and if they do, we will have an economic disaster on our hands without this authority. Of course, if we had done this, Lehman would have failed the next day. So we started doing a lot of contingency planning.

I would just say one other thing right now. My book on the financial crisis is about the collision of markets with politics, because this all happened weeks before a Presidential election. This is very much about the collision of politics and markets. The other thing the book is about is men and women who trusted each other, from different departments, agencies, or branches of government—from different political parties—working together, pooling their powers and authorities to deal with a crisis where we didn't have adequate authorities. But how we worked together as a team, to combine our authorities, skills, and experiences is a positive story. We started working together shortly after I arrived in DC. We'd been working together for some time when the crisis hit.

Riley

Hank, may I interrupt with a question?

Paulson

Yes.

Riley

I don't want you to lose your train of thought on this, but the question is a hypothetical: Could you walk us through what would have happened if you had let Bear Stearns go? I don't know practically what.

Paulson

I think we would have had a catastrophe that was at least as bad as the Great Depression, given the amount of concentration we have with a handful of big banks and investment banks controlling well over one-half of our banking assets. Look what happened when just Lehman failed. If Bear had failed, Lehman would have gone down immediately, and it would have ignited a fuse which would have set off a devastating chain of serial bank failures. I don't know how we would have put it back together. Bear Stearns, in and of itself, wasn't that big. In good times, they could have failed, and it could have been managed. But these were not normal times. The crisis had been building for some months, the system was overleveraged and fragile and we didn't have the necessary emergency powers to stop a panic. Bear was intertwined with the rest of the financial system, so it would have been a trigger point. The whole system was so weak, I think Lehman would have gone. And we had not yet stabilized Fannie or Freddie, which combined about $5.4 trillion of securities. I hate to even imagine it. There would have been more unemployment than we had after the Great Depression.

So after Ben Bernanke and I talked to Barney about Lehman, I made remarks in June about needing emergency resolution authorities for a failing nonbank. Then I made a speech in the UK in July, outlining the way these authorities should work. I didn't refer to Lehman for obvious reasons. The Fed put their examiners in the investment banks, and opened up their discount window to the investment banks, hoping that would inject confidence into the market. There was all kinds of work evaluating different scenarios, strategies for preventing or dealing with a Lehman failure. We successfully encouraged Lehman CEO Dick Fuld to sell equity twice, and tried unsuccessfully to get him to sell Lehman or find a strategic investor. I don't believe, even if Dick had been realistic, that it would have been easy for Lehman to find a buyer or a strategic investor, because the market knew Lehman had many bad assets and a big capital hole, because Fuld had gone all around the world looking for strategic capital or a way to unload Lehman's problem loans.

The big global investors who came in early on to help the weakest banks weather the crisis, CIC [China Investment Corporation] in China, the Saudis, the Kuwaitis, the Singaporeans, with investments in Morgan Stanley, Citi, and Merrill Lynch, all lost a lot of money. There weren't a lot of willing capital providers because the early rescuers had been burned by underestimating the severity of the crisis. As we were prodding Lehman to find a buyer to try to stave off disaster, Fannie and Freddie began to unravel. We had actually begun pushing then to raise capital over the weekend when we were rescuing Bear Stearns in order to try to create confidence in the market. On the Sunday of the Bear weekend, I had a conference call with Bob Steel; with Jim Lockhart, who was the Fannie and Freddie regulator; with [Richard] Syron and [Daniel] Mudd, who were the two CEOs, to get them to announce that they were going to raise capital. They both agreed they were going to raise capital. Fannie ended up raising it, Freddie didn't. So we started aggressively prodding the GSEs in mid-March.

Then after the Bear Stearns rescue, we had a meeting in Senator Chris Dodd's office, in which Dodd and Senator Richard Shelby, the Chairman and ranking member of the Senate Banking Committee, agreed with Mudd and Syron on a reform bill for Fannie or Freddie, and all parties stuck to our agreement, but legislation didn't move the way it was supposed to in Congress, because Congress was so divided over anything that looked like a bailout. And Fannie and Freddie legislation was by political necessity part of an overall housing bill that contained a provision that was actually quite modest to aid defaulting homeowners. This was vigorously opposed by most Republicans in the House who were against government funding for any mortgage relief or modifications as using dollars from prudent taxpayers to rescue imprudent ones who had overextended themselves, so the legislation really didn't go anywhere. It was too contentious and difficult. It was only sometime in late June when Fannie and Freddie started to fail that we were able to get Congress to act.

Let me talk about President Bush and my relationship with him, because he was, as I write about in On the Brink, going to be in New York the Friday on which we announced the bailout of Bear Stearns. He was going to be speaking at the Economic Club, doing a session with the editorial page of the Wall Street Journal. He had asked me to help him prepare and to give him some thoughts. He was putting in his speech a line that said, "we won't bail out a financial institution." I had said to him, before I'd heard about Bear Stearns's illiquidity, "I wouldn't say that. I don't want to do a bailout either and we won't call it a bailout. If it's a bailout, we'll call it a rescue. I don't think we'll have to do one, but I don't know for sure and why would you ever say that? Because you won't do it until you need to do it. You'll do a bailout if you have to do one. No one wants to do them." He said, "Well, I hear you, but I'm going to put this language in my speech anyway."

When I called him really early Friday morning after we had learned that Bear was failing—The great thing about him—You know the guy is an amazing guy, very disciplined. He was in his office at 7:00; I could always get him. I could go over and see him, walk right across the street, see him in his office, I could get him on the phone regularly. So when we did the Bear Stearns, as I wrote, I called him and I started off with a joke, "You can take that line out of your speech about no bailout." [laughter] He obviously did and he supported the Bear Stearns rescue.

He was an amazing leader during the crisis: quick on the uptake; understood markets; willing to support me in doing some unpopular, controversial, and unusual things. He also knew how to delegate. President Bush was a terrific example of leadership and true calm in crisis. Not only was he balancing all the stress of the financial crisis but he was also managing two wars. Yet, in the midst of what must have been grueling pressure, he was a rock. He said, "You're my wartime general. Keep me posted; come to me whenever you need to, but you do what you've got to do." He didn't make me go through the usual White House decision-making process. We made decisions at Treasury, kept the White House informed, and I stayed in regular contact with the President. He actually came over a couple of times and saw me at Treasury, and I saw him regularly in the Oval Office and talked with him frequently on the phone.

He was a great help to me because he could see the crisis was taking a strain on me. He would buck me up; he would tell me to sleep, to work out. He would say, "I would do more to help you with Congress, but it would hurt you if I tried to help you with the Democrats." He gave great advice, he understood the politics, and was a quick study on markets. If there's anybody who didn't want to be bailing out the Wall Street banks or GM and Chrysler, who had had a low opinion of Wall Street and the autos, it was George Bush. He was just absolutely determined to do what was right all the time. I could talk with him and have a conversation quicker with him on these market-related things than many others who I'm sure were very bright, much smarter than either he or I are in terms of IQ [intelligence quotient] or are policy whizzes. But on these things, gosh, he understood quickly and he would come back with analogies. When we were guaranteeing the money markets or the things we did, he had a feel for markets. I don't know, maybe it was from his days in the oil business in Texas, maybe because he just understood politics the way he did, and business. He had a Harvard MBA [master of business administration degree].

He didn't ask so many questions that it was painful, but he really knew how to ask the right ones, and we worked well together. If he hadn't been there, I don't know what would have happened. During one of the darkest days, when I thought Citibank might fail, he said, "Hank, you and I were very fortunate that we are here now." And I'm getting way ahead of myself, but he said, "You should be glad you're here. You should welcome this, because the country needs you and you've trained during your career for this. Just think what would happen if we had this crisis early in our administration, or at the beginning of an Obama administration, when a new President is just learning how to work with his Treasury Secretary. REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT. I have someone who knows what to do. I trust you, you trust me, we'll do what's best for the country. Who cares what the polls say?" And when I would come and give him bad news, he never shot the messenger. He just immediately was upbeat and would say, "OK, what do we do and how do we do it?" So anyway, he was a very strong leader.

Riley

Did he give you occasional redlines?

Paulson

No, never.

Riley

I actually owe you a break.

Paulson

Yes, I'll take one, yes.

Riley

Why don't we take five minutes then?

Paulson

He never once gave me a redline, but he didn't have to, because I checked with him. I knew who the boss was, so I did the work, but I never once took a major action or anything without going to him.

Riley

Right.

Paulson

I went to him. I'd go see him, I'd do it on the phone, on everything. The only time we really went through the White House staff and we went through the process was on autos, and on autos, Joel and I had lunch with him and decided it all before, but we went through the process.

Riley

All right, let's take five minutes and let you catch your breath.

[BREAK]

Paulson

I won't spend a lot of time on this, because you obviously know this, and because I'm sure everyone else has told you this, that there are two different George Bushes. If you're in a small meeting with him, he comes across the way he is: smart, knowledgeable, knowing what questions to ask, attributes of a good leader. Then you would watch him stand up publicly, when he gets that smirk on his face sometimes and so on, and you couldn't understand it. I had one experience with him early on, when he was getting together with a group of CEOs. I remember one of the guys was the CEO of Under Armour, Kevin Plank. And this is something I thought I did very well. I can sit down with a group of CEOs and ask questions, have a conversation about economic conditions, their opportunities, challenges, leadership, et cetera. In any event, he included me in his CEO round table and I was really impressed. I thought, By gosh, this guy hasn't run an investment bank, and he does this better than I do. He's really, really good. Then he said, "OK, everybody, let's bring the press in." So they brought the press in and I thought, My gosh, I'm a novice with the press, but I could do as well as he's doing. He wasn't natural, he wasn't articulate, he seemed a bit defensive.

Riley

Right.

Riley

How do you explain the two?

Paulson

I can't explain it, because he was a good politician, was great with people; he was good one on one. I watched him on a number of occasions where I just was in awe. REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT

REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT

REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT

REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT

Riley

REDACTED

Paulson

REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT What was unusual was a disconnect when he talked with the press. I thought I'd just make that point—you all know that.

Riley

Well, we know it partly because we hear it. Barbara and I both, and maybe others of you, have had the privilege of being in small groups with the President, and have actually witnessed what you talked about, but it's still a puzzle and it's the kind of thing that if you're trying to communicate to generations down the road, something about—

Paulson

Josh Bolten would have to explain it. People explain different things to me and explain what happened when he first came in, you know when he tried working with the European leaders and they hit him with Kyoto and climate, and he got on the wrong side of some of that, and some of the experiences he had early on with the press or whatever. I can't explain it. But it was extraordinary to watch someone who could be so natural and powerful a communicator in private settings revert to a stiff recital of his talking points with the press.

Riley

Right.

Paulson

REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT

Rodriguez

I think we sometimes learn things about Presidents that are 180 degrees wrong and yet they stick. Gerald Ford is not a clumsy person; he was an athlete, and probably the best athlete—

Paulson

President Bush was the best athlete in the White House.

Rodriguez

And Jimmy Carter was not indecisive. He had problems and they tended to be on the other side, being stubborn and sticking to things longer than he probably should have.

Paulson

And being incredibly naive.

Rodriguez

So the pictures that we think, people on the outside, are true about those individuals, are often wrong, and then once they're in place, almost impossible to remove.

Paulson

REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED

REDACTED TEXT I am now, after Bear Stearns, posting the President regularly about various concerns, et cetera, and about how it's a tough situation and how bad the situation is in the capital markets. You can't see—When people look at the stock market, they don't look at the interbank funding market. They don't look at the different indices we were looking at or have the market intelligence I regularly received from a broad spectrum of market participants, but I saw that the system was stressed and fragile.

So then Fannie and Freddie started to unravel. The price of their securities declined, credit spreads blew out, their stock dropped, et cetera. There's a big misconception about Treasury. People think Treasury Secretaries have all kinds of power, but study it sometime. The Treasury Secretary has an important position and the power he has is what the President gives him. He doesn't have power over independent regulators. He has to go to Congress to get legislation or raise the debt ceiling. The President can delegate a lot, but—And Treasury did not have people, when I was there, who knew how to analyze and look at financial institutions, do risk analysis, or any with the investment banking or deal making or transaction structuring skills. The Treasury had really good policy people, economists, hardworking, smart, apolitical, never prone to leaks, but they didn't have practical financial analysis, financial engineering experience.

And we weren't Fannie and Freddie's regulator, that was OFHEO [Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight]. Also, we didn't have access to the nonpublic information their regulator had. We only had public financials, which were insufficient. And then, on top of that, even OFHEO, their regulator, didn't understand the extent of the problem; they didn't have the capabilities or capacity. So when these institutions started to go down, I knew that I would need to go to Congress and get emergency powers. REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED TEXT REDACTED