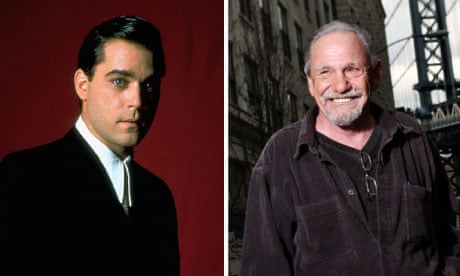

Henry Hill has died – of natural causes. It is an anti-climactic end for the Brooklyn mobster and FBI informant whose life story inspired the classic Martin Scorsese movie Goodfellas, with Hill played by Ray Liotta. Henry didn't die the way he expected to. He got whacked in hospital by heart failure at the age of 69, and not by the deadpan wiseguy he reportedly anticipated every day of his life, exacting revenge for his betrayal. He thought that one day he would open the door to an old friend who would calmly hold up a gun. Instead it was Father Time, wielding a scythe.

The revenge-slaying endgame was perpetually raised by Hill in all the many interviews he gave since the release of Scorsese's movie in 1990. He told anyone who would listen that he simply couldn't believe he hadn't been murdered yet. After all, he had ratted out a lot of important guys, a betrayal immortalised in a hit film. The tinge of real danger undoubtedly added to Hill's prestige and authority. We all thought that, at any moment, Hill would die in the awful ice-cold way shown in Goodfellas, when Joe Pesci's mercurial gangster Tommy DeVito is shown into a basement, expecting to be promoted to "made guy" status, but realising too late that he is about to be killed ("Oh no … !").

So why didn't Hill get his bullet in the head? After all, his testimony secured 50 convictions. Perhaps the mobsters were subtle sadists. Why put Henry out of his misery, when they could string him along, let him sweat? Or perhaps it was something else: Hill was famous. Liotta and Scorsese had made him a legend, and mobsters are notoriously infatuated with celebrity, their own and other people's. Perhaps fame gave Hill a free pass.

There's a third possibility: organised crime is very disorganised – as chaotic, incompetent and forgetful as other organisations. (Goodfellas and TV's The Sopranos do a good job of conveying this.) Maybe no one got around to whacking Hill, or each mafioso thought it was someone else's job.

The final possibility is the most banal. There's nothing so unreliable as a criminal's self-aggrandising memoirs. Could it be that his betrayal wasn't quite so uniquely dramatic as it appeared, or that Hill personally didn't make that much of an impression, and that the criminal fraternity had a lively appreciation of the fictional touches in his gangster identity? We shall never know. At any rate, Henry Hill sleeps, but not with the fishes.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion