‘The Queen of Soul” was an honorific thrust upon Aretha Franklin by the Chicago radio DJ Pervis Spann during her first flush of fame, but it ended up being a job for life. When, decades later, Mojo and Rolling Stone ran polls to find the greatest singer of all time, she topped both and nobody was either surprised or disappointed. You could have tallied the votes any time since 1967 and got the same result, because Aretha is the singer all others are measured against. “When it comes to expressing yourself through song, there is no one who can touch her,” Mary J Blige testified in her Rolling Stone tribute. “She is the reason why women want to sing.”

Some artists, such as James Brown, set out to start a musical revolution. Aretha became a revolution by incarnating powerful ideas and desires that were sloshing around seeking a vessel strong enough to contain them. If you go back and read what was said about her when she broke through you realise just how significant she was. In 1967, Jet magazine equated her impact with that of Black Panther H Rap Brown and the Detroit riots by calling it the summer of “’Retha Rap and Revolt”. Comedian and activist Dick Gregory explained her importance as a civil rights figurehead by saying, “You’d hear Aretha three or four times an hour. You’d only hear [Martin Luther] King on the news.” Franklin’s publicist Bob Rolontz told biographer Mark Bego: “‘Soul’ was Aretha. Aretha came, and Aretha conquered and made the soul trend happen because it sort united all the rest of the artists behind her. She hauled them along in a mighty wake.”

None of these claims felt like exaggerations yet none of them came from the woman herself, who saw her role in humbler terms. “I sing to the realist,” she once said. “People who accept it like it is.”

In Detroit in the middle of the 1950s, Aretha was already a big deal. As the daughter of Reverend CL Franklin, a powerful local figure who befriended Martin Luther King, Dinah Washington, Sam Cooke and gospel great Mahalia Jackson, she had a stage every Sunday at the New Bethel Baptist Church and she commanded it while still in her early teens. Her sisters Erma and Carolyn sang too but everyone knew Aretha was the star-in-waiting. “That one – CL’s girl – that’s the one to watch,” Washington said.

Aretha recorded her first gospel album, Songs of Faith, in 1956, aged 14, but she also appreciated blues, jazz, Broadway and doo-wop and picked up tips from Cooke, another singer who ended up migrating from church to secular music. “He did so many things with his voice – so gentle one minute, so swinging the next, then electrifying, always doing something else,” she remembered.

CL Franklin gave the transition his blessing but Aretha took a long time to get it right. John Hammond of Columbia Records, who signed the teenage Aretha in 1960 after hearing her on a songwriter’s demo cassette, later admitted that he “misunderstood her genius”. The nine albums of jazz, pop, R&B and show tunes that she recorded for Columbia weren’t as bad as they’re often made out to be but suggested an ongoing identity crisis – a light being hidden under a series of bushels.

By the time she joined Atlantic at the end of 1966 she was ready to find her real voice. She was 24, with a husband, three children and a decade of performing and recording under her belt. In short, she had lived. Atlantic’s Jerry Wexler turned her career around with a simple idea: “I took her to church, sat her down at the piano, and let her be herself.” After their first session together at Alabama’s Muscle Shoals in January 1967, recording the throat-grabbing I Never Loved a Man (the Way I Love You), the musicians were so astonished that they danced and sang and hugged each other with joy.

It was the first of five consecutive Top 10 singles in one spectacular year. Aretha’s career, becalmed for so long, was suddenly rocket-powered, as if America had been waiting for someone just like her. The mayor of Detroit declared 16 February 1968 to be Aretha Franklin Day and Martin Luther King himself presented her with an award; that August she sang The Star-Spangled Banner at the Democratic National Convention. Her albums went gold, her shows sold out and every talk show wanted her as a guest.

Between 1967 and 1972, Aretha released eight classic studio albums and three live ones, showcasing a voice that sent listeners scrambling for the keys to its uncanny power. Fans and critics spent a lot of time pondering the definition of soul but they all agreed that this is what it sounded like. In fact, her voice’s perfect alloy of pleasure and pain, suffering and endurance, sex and spirituality, virtually constituted a scientific formula. “This is a voice that has not only sound but a smell and a depth,” said poet Nikki Giovanni. “A taste. You hear Aretha, but you also lick your lips.”

Wexler thought that Aretha had the full package of “head, heart and throat … The head is the intelligence, the phrasing. The heart is the emotionality that feeds the flames. The throat is the chops, the voice.” It made her a spectacular interpreter of other people’s songs. She only took hold of a song if she could feel it in her bones and, once she did, it was changed forever. “I just lost my song,” said Otis Redding after hearing her blazing feminist revamp of Respect. “That girl took it away from me.” On Aretha Arrives (1967) alone, she tackled songs associated with Frank Sinatra, Willie Nelson and the Rolling Stones and she later unearthed the gospel classics hidden inside Let It Be and Bridge Over Troubled Water.

But she wasn’t just a great singer. She was also a charismatic pianist and a shrewd and conscientious arranger, mapping out songs before each session and then filling yellow legal pads with incredibly detailed notes on perfecting the final mix. While she benefited from fine collaborators such as Donny Hathaway, saxophonist King Curtis, backing singers the Sweet Inspirations and her sister Carolyn, Wexler called her “the central orchestrator of her own sound”.

Her performances were oceanic, as deep as they were wide. Once describing herself as “an old woman in disguise, 25 going on 65”, she sounded like a grown-up in a world of teenagers. Every listener knew that Aretha knew exactly what she was singing about. “If a song’s about something I’ve experienced or that could’ve happened to me, it’s good,” she said. “But if it’s alien to me, I couldn’t lend anything to it.”

Although she was a lifelong Democrat with a civil-rights activist father, Aretha did not embrace politics as fully as some of her peers. She was surprised that Respect captured “the need of a nation” the way it did, and that Chain of Fools became a hit with black troops in Vietnam. But she did release powerful versions of Curtis Mayfield’s People Get Ready and Sam Cooke’s A Change Is Gonna Come and recorded the blazing Think, with its battle cry of “Freedom!” just days after King’s funeral. By the early 70s, she was wearing an afro and a dashiki and naming an album after Nina Simone’s Young, Gifted and Black. An interviewer visiting her Manhattan apartment in 1971 noticed political texts by Frantz Fanon and Herbert Marcuse on the shelf. She was perhaps more radical in private than she was in public.

Even when her words resisted any kind of political reading, though, her voice spoke volumes. These were hard times and she was strong enough to take the weight. “Soul music is music coming out of the black spirit,” she said. “A lot of it is based on suffering and sorrow, and I don’t know anyone in this country who has had more of those two devils than the negro.” She might have added that black women were particularly attuned to these two conditions. On black feminist anthems such as Respect, Think and Young, Gifted and Black, she sounded indomitable, drawing strength from the social movements of the time and repaying it twice over. “I suppose the revolution influenced me a great deal, but I must say that mine was a very personal evolution,” she reflected. Ray Charles said that Aretha sang “the way black folk sing when they leave themselves alone”.

So much praise and expectation could turn anyone’s head, and Aretha certainly developed diva tendencies, but she liked to downplay her own exceptionalism and say that she felt the same pain that everybody did – it’s just that she could sing that pain better than anyone else. And while the press fixated on her personal struggles to an intrusive degree (she divorced her abusive first husband Ted White in 1969), she didn’t fetishise suffering in the vein of Billie Holiday. This daughter of the church was always moving on up, always overcoming. She might bend but she would never break.

Between 1968 and 1975, Aretha won the Grammy for best R&B female vocal performance every single year, until people started to nickname the award “the Aretha”. Her lover Ken “Wolf” Cunningham called the early 1970s “the Age of Aretha”. As she hit that decade, her songs grew longer, looser and tougher. Aretha Live at Fillmore West (1971) captured her wowing a mixed-race audience in the hippie heartland with hard-rocking arrangements and a spontaneous duet with Ray Charles. She honoured her gospel roots by recording the double-platinum Amazing Grace (1972) in a Baptist church. The 11-minute title song was so moving that the choir leader and old family friend, the Reverend James Cleveland, broke down in tears at the piano and had to leave the session. With compositions such as Rock Steady, Day Dreaming, Call Me and the title track of Spirit in the Dark (1970), she made a case for herself as a formidable singer-songwriter, not just an interpreter of other people’s material.

After this creative high, however, she wobbled badly, with the Curtis Mayfield-produced Sparkle (1976) the sole highlight of a pretty wretched run. “At times she has been guilty of what I call oversouling – too much screaming and melisma,” Wexler told soul historian Gerri Hirshey. “And I would question her choice of material. A lot of it just hasn’t been up to her gifts.” Agnostic about disco, she turned down the Chic songs that became rejuvenating hits for Diana Ross. She also frustrated old fans with erratic behaviour and fussy concerts where the costume changes ate up more time than the music. In private, she wrestled with the worst depression of her life. Her star had fallen so dramatically that in Steely Dan’s 1980 hit Hey Nineteen, the sleazy narrator bemoaned his teenage lover’s ignorance: “That’s ’Retha Franklin / She don’t remember the Queen of Soul / It’s hard times befallen / The Soul Survivors.”

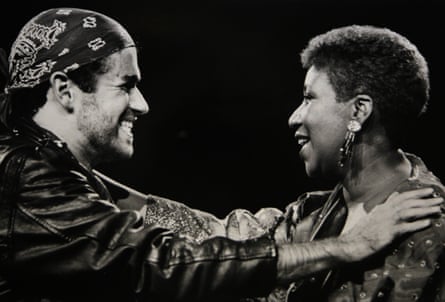

The 80s were a tough decade on a personal level. She lost her father and just four years later, one of her sisters, Carolyn (her mother had died in 1952). The singer also developed a fear of flying that confined her to Detroit. But her career rebounded. When she sang Think in the film The Blues Brothers, the New Yorker’s Pauline Kael marvelled: “She smashes the movie to smithereens. Her presence is so strong she seems to be looking at us while we’re looking at her.” She moved from Atlantic to Arista, where Jump to It (1982), produced by superfan Luther Vandross, took her back to No 1 and Who’s Zoomin Who? (1985) went platinum. That album’s hit duet with the Eurythmics, Sisters Are Doin’ It for Themselves, was followed by an even bigger one with George Michael, I Knew You Were Waiting (for Me) – her first US No 1 since Respect. In 1987, she became the first woman inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

After some less successful attempts to modernise her sound, she achieved another, more modest comeback with 1998’s A Rose Is Still a Rose, working with Lauryn Hill and Puff Daddy. Demonstrating her rejuvenated range since she’d stopped smoking six years earlier, it came out just months after she filled in for a sick Pavarotti on Nessun Dorma at the Grammys: hip-hop and opera in the same year. In 2014, after another batch of disappointments, Aretha Franklin Sings the Great Diva Classics found her tackling songs by women from Etta James to Alicia Keys. Her version of Adele’s Rolling in the Deep made her the first woman to earn 100 hits on the Billboard R&B chart, 54 years after her first.

She didn’t really need to chase modernity, though. When she performed at Barack Obama’s inauguration (as she had done for Bill Clinton and Jimmy Carter), she was as much a symbol as a voice, an essential part of the American story. What she achieved during her first six years on Atlantic burned her indelibly into popular culture and granted her a stature that no amount of misguided flops could diminish. She was the living definition of soul and, once she set aside her youthful modesty, she didn’t mind acknowledging it. “My voice is better than ever, because of experience,” she told Mark Bego in the late 1980s. “At the risk of sounding egotistical, it just gets better. I am my favourite vocalist.”