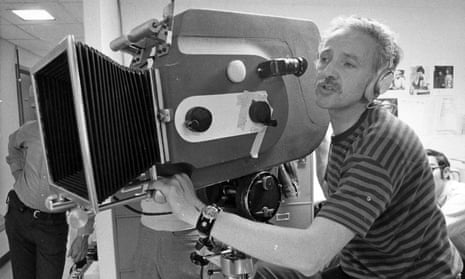

One of the world’s most accomplished cinematographers, Haskell Wexler, who has died aged 93, was nominated five times for an Academy Award, and won for Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) and Bound for Glory (1976). Wexler worked equally on mainstream and independent films, fiction and documentaries, monochrome and colour. Yet, rare in cinematographers, most of whom are hired hands, he created a relatively homogeneous filmography and never swerved from his radical convictions.

These were instilled in him from an early age. Son of Simon and Lottie Wexler, he was born into a wealthy liberal Jewish family in Chicago, who sent him to the progressive Francis Parker school, where his best friend was Barney Rosset, who later became the owner of the iconoclastic Grove Press. At the age of 12, while he and his family were on holiday in Italy, Haskell used a 16mm Bell & Howell camera to film uniformed fascist youths, which he later intercut with home movies of his two brothers and parents.

After a year at the University of California, Berkeley, Wexler joined the merchant navy as a seaman during the second world war, serving four and a half years. He was decorated for bravery after he rescued some of his crew members when his ship was torpedoed in shark-infested waters off the coast of South Africa.

After the war, his father helped him to open a studio in Des Plaines, Illinois, where he produced a number of industrial films with an underlying social message. After closing the studio in 1947, he photographed some documentaries by the educational film-maker John W Barnes. Wexler and Barnes co-directed and co-produced The Living City (1953), nominated for an Oscar for best documentary short.

An instructional film, it dealt with urban problems such as how existing slums are to be eliminated and how to deal with congestion. “How did our cities get this way,” narrated Studs Terkel. “I was in bombed-out cities in Europe in the war. And then I came back to Chicago to this. We need to tear down the slums, and build up new affordable housing.”

Wexler continued in the documentary tradition, mixing cinéma vérité and fiction narrative conventions. The first feature Wexler shot was the low-budget Stakeout on Dope Street (1958), directed by Irvin Kershner, about three teenagers (one played by Yale, Wexler’s brother), who find two pounds of uncut heroin and try to peddle it. Because he had difficulty becoming a member of the restrictive Hollywood Guild, Wexler shot the film under the pseudonym of Mark Jeffrey (the names of his two sons). Using handheld cameras for the first time, he shot the film on location rather than in a studio.

After Wexler was allowed to enrol in the Hollywood International Photographers Guild as a first cameraman, he linked up with the director Joseph Strick (who co-directed with Ben Maddow and Sidney Meyers) to make the semi-documentary The Savage Eye (1959). Wexler established an unflinching, realistic style for the film, which looks at the more bizarre aspects of life in Los Angeles seen through the eyes, more jaundiced than savage, of a divorcee.

Wexler remained active in the 1960s, shooting mostly black-and-white naturalistic dramas such as Kershner’s The Hoodlum Priest (1961) and A Face in the Rain (1963), for which he is credited with inventing the handheld running shot by running with an actor down a narrow alley; Elia Kazan’s America, America (1963); Franklin J Schaffner’s The Best Man (1964); and Mike Nichols’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

In the last of these, his penetrating cinematography explored the faces of the two stars, Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, in large, unflattering close-ups as they squabbled bitterly. However, Wexler used dimmers and umbrellas on single-source lights to soften the intensity. The exteriors were dark, broken by washes of light glowing from an unseen source. In the scene where the bickering couple stand outside a roadside restaurant, spotlights glare into the lens while neon lights burn in the background.

When Wexler began to use a handheld camera on the film, “all the old-timers would walk away, and there would be a lot of snickering,” he said. As this was the first movie directed by Nichols, his reliance on Wexler was incalculable.

In contrast, Wexler then turned to making two mainstream films in colour directed by the veteran Norman Jewison. In the Heat of the Night (1967) had a realistic background – a steamy, ignorant town – against which the two main characters, a black detective (Sidney Poitier) and a bigoted police chief (Rod Steiger), played a game of dominance. The quite ingenious plot of The Thomas Crown Affair (1968) was overlaid with multiple images, splitscreen and zooms. For the heist scene, Wexler used four cameras to capture the faces of the robbers and the precision of the robbery from different viewpoints, one with a long lens at a window overlooking the bank.

After this glossy entertainment with Steve McQueen and Faye Dunaway, Wexler turned back to more radical material, mostly documentaries, much influenced by the groundswell of protests against the Vietnam war and the civil rights movement. “The main difference in documentaries is that it’s closer to the skin,” he remarked. “You’re more in control, it’s more yours and maybe two other people that are working with you.”

His first fiction feature as director, albeit semi-fiction, was Medium Cool (1969), shot during the chaotic Democratic convention in Chicago in 1968. It tells of the politicisation of a TV news cameraman (Robert Forster) as he moves from one consciousness-raising assignment to another, while trying to prevent his personal life from collapsing. “Jesus, I love to shoot film!” the character declares, which was Wexler’s credo. The actual footage of the convention comes across dynamically, and there is one unstaged moment when the director is hit by teargas.

Wexler, reunited with Strick, photographed (with Richard Pearce) the 22-minute Oscar-winning documentary Interviews With My Lai Veterans (1971). Although no footage of the massacre of Vietnamese villagers by GIs is shown, it is vividly (and horrifyingly) evoked by the five soldiers interviewed by an off-screen interviewer. The subjects speak candidly about how they learned not to question orders, even commands such as “shoot everybody”.

Wexler further investigated the American “crimes” in Vietnam with his 1974 documentary Introduction to the Enemy, which followed Jane Fonda and her then-husband Tom Hayden on a visit to Hanoi during the war, lending a sympathetic ear to the North Vietnamese. Also with Fonda, Wexler shot Hal Ashby’s Coming Home (1978), a tearjerker with a built-in criticism of the US policy in Vietnam.

Previously, also for Ashby, he had filmed Bound for Glory, a biopic of the folk singer Woody Guthrie (whom Wexler had met during his time in the navy), which splendidly evoked the trappings of the depression – migrant crop pickers, soup kitchens, hobos hopping freight trains, dust storms – in desaturated colour. It was the first feature in which the Steadicam was used, especially in an audacious shot where the cameraman started on a fully elevated platform crane that jibbed down until it reached the ground, where he stepped off and walked with the camera through the set.

Wexler was fired half-way through shooting One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) because of “artistic differences” with the director Milos Forman, and replaced by Bill Butler; they were jointly nominated for the best cinematography Oscar. But it was documentaries that most occupied Wexler in the 70s, including Underground (1976), a clandestinely shot interview with five leading members of the Weather Underground, a fugitive group seeking the violent overthrow of the US government. “We have a responsibility to show the public the kinds of truths that they don’t see on the TV news or the Hollywood film,” he explained. Wexler was in the files of the FBI as “potentially dangerous because of background, emotional instability, or activity in groups engaged in activities inimical to the United States”.

In the 80s, Wexler continued to use non-fiction film techniques creatively to heighten the tension and mood of a narrative film. “I don’t think there’s a movie that I’ve been on that I wasn’t sure I could direct it better,” Haskell said in the documentary Tell Them Who You Are (2004), directed and produced by his son Mark.

His radicalism undimmed, Wexler’s second fiction feature as director, Latino (1985), had an underlying criticism of American support of guerrilla forces attempting to overthrow Nicaragua’s Sandinista government, and in his later years, he made films that gave voice to the voiceless – from The Sixth Sun: Mayan Uprising in Chiapas (1995) to From Wharf Rats to Lord of the Docks (2007), about a union leader.

He is survived by his third wife, the actor Rita Taggart, his children, Mark, Jeff and Kathy, and by his sister, Joyce.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion