When he was a floppy-haired 12-year-old kid from working-class western Sydney, Harry Kewell, along with his team-mates in the state title-winning Marconi Stallions’ Under-13s squad, was asked by coach Stephen Treloar to imagine what he would like to have achieved in football by the time he was 40. It might have made as much sense to ask a 12-year-old what life would be like if he were a unicorn, but Kewell, says the highly-regarded Treloar, gave the question serious thought and wrote down his answer.

Treloar then followed up that question with others. What would you like to have achieved in football in 10 years, in five years, in three years, in one? Kewell, says Treloar, though popular with his team-mates, was “his own man” and he had an arrogance born of confidence in his own ability. “And I mean that in a nice way,” says Treloar, today the director of postgraduate studies in the school of business at the University of Notre Dame (Australia). “Harry was the kid who said, ‘C’mon, see if you can get the ball off me’.” Kewell’s written answers, of which Treloar still has the original copy, were reflective of that, while also proving prescient.

Kewell wrote that he wanted to represent the junior NSW side, the Under-17 and Under-20 national sides, to play senior football for Australia, and – by the age of 40 – to be a coach. “Every one of those goals he achieved,” says Treloar, who adds, by way of emphasising the single-minded drive that characterised the young footballer, that when he was asked to rate, from zero to 10, the importance of attaining each of those goals, “Harry wrote down ‘10, 10, 10, 10 and 10’.”

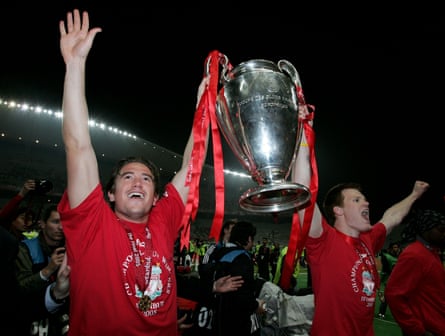

For all Kewell’s achievements there were plenty more than he listed during that Under-13s planning session, including winning the Uefa Champions League and FA Cup with Liverpool, and playing a major role in the success the Socceroos enjoyed before, during and after the nation’s drought-breaking involvement in the 2006 World Cup. A three-time Oceania player of the year and the 1999-00 Professional Footballer’s Association young player of the year in the UK, Kewell was also named Australia’s all-time greatest footballer after a vote in 2012 that took in the verdict of fans, players and media. And on Tuesday evening Kewell, 38, now coaching Watford’s Under-21s team and aiming to be “a top manager in Europe”, will formally accept the Alex Tobin medal – selected by the executive of Australia’s PFA – for his achievements, service and dedication to the game.

And yet, for all that, when Kewell’s name is raised among a collection of Australian football fans or pundits (a “froth” would be a fitting enough collective noun) it’s not unusual to find that the discussion tends to explore various reasons Australia has never quite taken Kewell to its heart. At least in the same, unabashed way it has some of his arguably less-talented, though highly-accomplished, former team-mates like Tim Cahill.

There’s no science to love, of course, but if this is indeed true I wonder if it’s because, at least in part, we hold Kewell responsible for the promise we tend to believe he never quite fulfilled, for clubs and country. That this was largely due to his fragile body is neither here nor there. Quite simply, Kewell, who had as sweet a left foot as Christy Brown, was so exhilarating to watch in the first half of his career that we wanted it to go on forever. And when it didn’t, when he was cruelled by a litany of injuries, we felt he cheated us. So it became easier to define Kewell for what he didn’t give us than what he did.

Kewell’s time at Liverpool, for instance, was an injury-plagued disappointment, and he went under the surgeon’s knife seven times in six seasons. No doubt there were many at Leeds, heartbroken by the manner of his departure, who experienced the bitter-sweet taste of schadenfreude. (Leeds fans would later find more reason to poison the well of their memories when Kewell, released by Liverpool, signed for Galatasaray, eight years after two Leeds fans were stabbed to death by a Turkish football fan in Istanbul before a Uefa Cup semi-final between the two teams). Although, on Merseyside, Kewell provided a few moments of incandescence – brighter still for the gloom surrounding them – even his major successes there had to be qualified. Yes, he played a part in Liverpool’s victories in both the iconic 2005 Champions League final, and the remarkable 2006 FA Cup final, but on both occasions he had left the field at the point in the fairytale when Liverpool were lost in the foreboding woods.

Kewell’s time with the Socceroos was, on the whole, much happier than that. His influential turn on the do-or-die 2006 World Cup qualifier against Uruguay, and his late equalising goal in the 2006 World Cup against Croatia that sent the Socceroos into the second round, would have been enough on their own to cement his star in Australian football. In a golden generation he was Midas, a highly marketable player with boy-band looks and that “cool”-sounding name who was as responsible as anyone for the success of the national side, and for attracting a new generation of Australian fans to the game. Kewell even contributed to changing the way football was played in Australia.

He did this by playing the game in a way that held more natural appeal to children than the prevailing boot-it-to-the-shithouse style built on a bedrock of lungpower and muscle. Kewell had about him trickery, audacity, and a little bit of magic. While other players were chasing rabbits, he was pulling them out of his hat. “He was always a player with finesse,” recalls Treloar. “I think that came about because as a junior he often played in higher age groups than his own. He couldn’t be that robust, knock-em-down player so he developed a different set of skills.”

His former Leeds team-mate and now football commentator, Michael Bridges, says Kewell was a special player with similarities to John Barnes and Chris Waddle, left-footers with Brazilian flair. “I think he came to influence the way the game is played here [in Australia] because kids want to emulate players who are exciting. And Harry was that,” says Bridges (who, as an aside, says he was convinced to drop his “north-east diet of fish and chips” after observing Kewell’s dietary discipline and professionalism). “He could drop the shoulder and be past a player in a flash. He had that quickness, that skill. But he worked at that. In the gym, on the field, always staying back after training to putting in that bit extra.”

But as with his club football it wasn’t all plain sailing for Kewell on the international front. Though debuting as a 17-year-old, Kewell made just 56 appearances for the Socceroos over a 17-year period between 1996 and 2012. One of the games he missed – due to an infected toe – was one of the most significant in Australia’s football history; their round of 16-match against Italy in the 2006 World Cup.

On other less significant occasions Kewell’s loyalty to the jersey was questioned, with many fans and pundits often wondering whether the injury of the day that ruled him of a Socceroos match was real or whether it was an excuse thrown out by Leeds or Liverpool – or indeed Kewell himself – because his absence would be inconvenient. Kewell, more comfortable posing in his underpants for a sponsor than talking into a microphone, was often forced to defend himself against such accusations. And when he did so he sometimes came across as aloof or arrogant.

That’s not who he is, says Bridges. “Harry’s actually a very shy character, and that gets misread by some. I don’t think he’s always been embraced as he should have been by Australians or Football Federation Australia, for that matter.” Kewell’s credibility has been unfairly damaged at times, he says, something which he believes owes a lot to Australia’s so-called tall-poppy syndrome as much as the suspicion over his many injuries. You can’t help but think that Kewell’s decision in 2010 to allow an Australian 60 Minutes team to film him laid out in an operating theatre, with tape over his eyes, getting groin surgery in Sydney, was in some way a means of saying, “See? See? I’m not faking it!”

Ah, but look what’s happened, we’ve gone off track, dwelling on what Kewell never managed to deliver than what he did. Let’s rectify that.

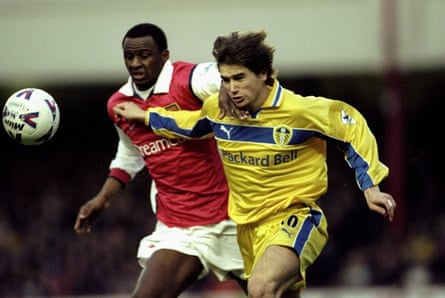

Take yourself back to the years between 1996 and 2003 when Kewell was an instrumental figure in coach David O’Leary’s youthful Leeds side that variously included the likes of Jonathan Woodgate, Alan Smith, Ian Harte and compatriot Mark Viduka. For five seasons between 1997 and 2002, Leeds finished no lower than fifth and they made the Champions League semi-finals in 2000-01. History will show that that wasn’t enough to recover expenditure – and fire sales, and a fall from grace, soon followed – but for a time, Elland Road was a very happy place.

Now there’s no pleasing everyone, particularly Leeds fans as he’d discover for himself in due course, but for that period of time Kewell – dubbed the Wizard of Oz – was doing a pretty good job of it. If you loved football and could see beyond tribal loyalties how could you not enjoy the way in which the young Leeds winger was lighting up the Premier League?

Another former team-mate and England defender Danny Mills recently described Kewell as “the Gareth Bale of his time”, though he was probably closer in skill and style (though not durability) to a contemporary – Manchester United’s rubber-hipped left winger Ryan Giggs. Set loose on Leeds’ left wing, but given licence to roam by O’Leary, Kewell, quickly won over Elland Road as well and Premier League fans who noted, with interest, that the young Aussie had an English father. Might he be nudged into representing England? Like Giggs, Kewell was whippet quick and his close-in dribbling was done with a touch so soft he might have had cushions strapped to his laces. Though he scored plenty of fine goals with his right foot, his left was his weapon and he could use it as an artist uses a brush or as a blacksmith wields a hammer.

In a Premiership match against Arsenal in May 2003, for example, he opened the scoring with a simply stunning strike. Running onto a lofted through ball from Jason Wilcox, Kewell, out-pacing Martin Keown and Oleg Luzhny, allowed the ball to bounce over his left shoulder and into his path. A fraction of a second after the ball bounced for a second time Kewell, a metre outside the left edge of the box, swung his left leg across the flight and drilled the ball into the left corner of the goal, past a diving David Seaman. The sumptuous half-volley drew an orgasmic “Ohh!” out of commentator Andy Gray.

Another day, in 2000, away to Sheffield Wednesday, Kewell picked up the ball in a central position a few metres outside the D. As Wednesday’s players fatally stood off him, Kewell took a soft touch as if contemplating his options. Then, though the ball sat before his right boot, Kewell took the least conventional of those. All but standing still he raised his left and used the outside of it to clip the ball under its chin to send it arcing out and in, finding the top right corner despite the efforts of goalkeeper Kevin Pressman. Then, casually, as if he’d done something as satisfying, but ultimately unremarkable, as successfully reverse-parking a car in front of a new girlfriend, he turned around, kissed his fingers, and gave them a little waggle. He barely raised a grin. In that moment, as in many others, he showed why Leeds fans adored him, why England fans wanted him, and why Socceroos fans were so damn happy to have him.

Kewell did admit, a couple of years ago, that he does sometimes wonder “what if”; what if he hadn’t had those injuries, “what could have been”. In that respect, he’s like many of us, looking at the glass half-happy. Perhaps time will fix this inclination and as the years pass he, like us, will be more inclined to reflect on what was, and enjoy the view. It was spectacular.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion