Boundless US History

HomeStudy GuidesBoundless US History

Menu

Ancient America Before 1492

European Encounters with the New World

Britain and the Settling of the Colonies: 1600-1750

Expansion of the Colonies: 1650-1750

The Colonial Crisis: 1750-1775

The American Revolution: 1775-1783

Founding a Nation: 1783-1789

The Federalist Era: 1789-1801

Securing the Republic: 1800-1815

Democracy in America: 1815-1840

The Market Revolution: 1815-1840

Religion, Romanticism, and Cultural Reform: 1820-1860

The Westward Movement and Manifest Destiny: 1812-1860

Slavery in the Antebellum U.S.: 1820-1840

A House Dividing: 1840-1861

The Civil War: 1861-1865

Reconstruction: 1865-1877

The Gilded Age: 1870-1900

The Gilded AgeThe Second Industrial RevolutionThe Rise of the CityThe Rise of ImmigrationLabor and Domestic TensionsThe Transformation of the WestCorruption and ReformCivil Service ReformThe Agrarian and Populist MovementsCulture in the Gilded AgeAmerican ImperialismConclusion: Trends of the Gilded Age

The Progressive Era: 1890-1917

World War I: 1914-1919

The Roaring Twenties: 1920-1929

The New Deal: 1933-1940

From Isolation to World War II: 1930-1945

The Cold War

Politics and Culture of Abundance: 1943-1960

The Sixties: 1960-1969

The Conservative Turn of America: 1968-1989

Bush, Clinton, and a Changing World

Hamilton's Economic Policy

Hamilton's Legacy

Alexander Hamilton's broad interpretation of Constitutional powers has influenced multiple generations of political theorists.Learning Objectives

Describe Alexander Hamilton's vision of federal governmentKey Takeaways

Key Points

- Alexander Hamilton was President Washington’s Secretary of the Treasury and an ardent nationalist who believed that a strong federal government could solve many of the new country’s financial ills.

- Hamilton published a series of essays with James Madison and John Jay known as the Federalist Papers, through which Hamilton supported the ratification of the Constitution and defended its separation of powers.

- In the aftermath of ratification, Hamilton continued to expand on his interpretations of the Constitution to defend his proposed economic policies as Secretary of the Treasury.

- Credited today with creating the foundation for the U.S. financial system, Hamilton wrote three reports addressing public credit, banking, and raising revenue.

- In addition to the National Bank, Alexander Hamilton founded the U.S. Mint, created a system to levy taxes on luxury products (such as whiskey), and outlined an aggressive plan for the development of internal manufacturing.

- Hamilton's political vision remained consistently at odds with the Democratic- Republican belief in strict interpretations of the Constitution and limited power of a centralized government.

Key Terms

- republican: A political-values system stressing liberty and inalienable rights that has been a major part of American civic thought since the American Revolution.

- Federalist Papers: A series of 85 articles or essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay promoting the ratification of the U.S. Constitution.

Hamilton's Political Vision

Alexander Hamilton was President Washington’s Secretary of the Treasury and was an ardent nationalist who believed a strong federal government could solve many of the new country’s financial ills.Background

Born in the West Indies, Hamilton had worked on a St. Croix plantation as a teenager and was in charge of the accounts at a young age. He knew the Atlantic trade very well and used that knowledge in setting policy for the United States. A leader of the Federalist Party, he believed that a robust federal government would provide a solid financial foundation for the country.Constitutional Convention and Ratification

By 1787, Alexander Hamilton had served as assemblyman from New York County in the New York State Legislature and was the first delegate chosen for the Constitutional Convention. Even though Hamilton had been a leader in calling for a new Constitution, his direct influence at the Convention itself was quite limited; the Convention adopted very few of his proposals in the final draft of the document.However, after signing the Constitution, Hamilton took a highly active role in the successful campaign for the document's ratification in New York. He recruited James Madison and John Jay to defend the proposed Constitution through a series of essays (known today as the Federalist Papers) and made the largest contribution to that effort by writing 51 of the 85 essays published. Hamilton's essays and arguments were influential in New York state and elsewhere during the debates over ratification. In the Federalist Papers, Hamilton argued that the separation of powers in the new republican system would prevent any one political faction from dominating another (at the state and federal level) and, therefore, preclude the possibility of tyranny. Hamilton also expressed support for the Federalists' vision of a nation of self-sacrificing men of talent who could be trusted to contribute and partake in the political process.

Alexander Hamilton: Alexander Hamilton was the first secretary of the U.S. Treasury.

Hamilton's Programs

In the aftermath of ratification, George Washington became the first President of the United States in 1789 and appointed Hamilton as Secretary of the Treasury. In his new role, Hamilton continued to expand on his interpretations of the Constitution to defend a series of proposed economic policies.The United States began to become mired in debt. In 1789, when Hamilton took up his post, the federal debt was more than $53 million, and the states had a combined debt of around $25 million. The United States had been unable to pay its debts in the 1780s and was therefore considered a credit risk by European countries. Credited today with creating the foundation for the U.S. financial system, Hamilton wrote three reports offering solutions to the economic crisis brought on by these problems. The first addressed public credit, the second addressed banking, and the third addressed raising revenue.

The National Bank

In Hamilton's vision of a strong central government, he demonstrated little sympathy for state autonomy or fear of excessive central authority. Instead, he believed that the United States should emulate Britain's strong central political structure and encourage the growth of commerce, trade alliances, and manufacturing. In response to the debate over whether Congress had the authority to establish a national bank, for example, Hamilton wrote the Defense of the Constitutionality of the Bank, which forcefully argued that Congress could choose any means not explicitly prohibited by the Constitution to achieve a constitutional end—even if the means to this end were deemed unconstitutional.Hamilton justified the Bank and the broad scope of congressional power necessary to establish it by citing Congress' constitutional powers to issue currency, regulate interstate commerce, and enact any other legislation "necessary and proper" to enact the provisions of the Constitution. This broad view of congressional power was enshrined into legal precedent in the Supreme Court case McCulloch v. Maryland, which granted the federal government broad freedom to select the best means to execute its constitutionally enumerated powers. This ruling has since been termed the "doctrine of implied powers."

Opposition

Hamilton's political vision, which included an aggressive expansion of federal power, remained consistently at odds with the Democratic-Republican belief in strict interpretations of the Constitution. Furthermore, Hamilton intensified this split through his public criticisms of Jefferson, Madison, Adams, and Burr in the elections of 1796 and 1800. After he maligned Burr in the 1800 presidential election, Hamilton and Burr fought a fatal duel that resulted in Hamilton's death in Weehawken, New Jersey. The Burr-Hamilton duel has since become an event emblematic of the violent political divisions between Federalists and Democratic-Repuclicans in the early years of the republic.Lasting Legacy

Alexander Hamilton's broad interpretation of Constitutional powers has influenced multiple generations of American leaders and political theorists. Though the Constitution was ambiguous as to the exact balance of power between national and state governments, Hamilton consistently argued in favor of greater federal power at the expense of the states, especially in his efforts to strengthen the national economy. Hamilton's economic policies as the Secretary of the Treasury influenced the development of the U.S. federal government from 1789 to 1800. In addition to the National Bank, Hamilton founded the U.S. Mint, created a system to levy taxes on luxury products (such as whiskey), and outlined an aggressive plan for the development of internal manufacturing, arguing that Americans needed to produce their own goods to avoid excessive dependence on European powers. His constitutional interpretation of the Necessary and Proper Clause set precedents for broad federal authority that are still upheld in courts and are considered an authority on constitutional interpretation.Hamilton's Economic Policy

Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury, strongly influenced the financial policies of the United States during the Federalist Era.Learning Objectives

Analyze Hamilton's economic policy and how it contributed to his image of FederalismKey Takeaways

Key Points

- Hamilton wrote a series of reports offering solutions to the economic crisis during the early years of the Republic; these reports addressed public credit, banking, and raising revenue. Hamilton outlined three types of national debt that needed to be paid in full to stabilize U.S. currency and to give investors faith in the new political system: foreign debt, federal debt, and state debt.

- Hamilton proposed that the federal government assume all of the state debts remaining after the Revolutionary War as a means of efficiently streamlining repayment and ensuring that no state government defaulted on its loans.

- This proposal was vehemently opposed by Jefferson and Madison, who argued that taxpayers in states with little debt (such as Virginia) should not be required to assume the burden of other state debts.

- Against opposition, Hamilton proposed the First National Bank to improve the nation's credit under the newly enacted Constitution.

- Hamilton also helped draft proposals for the U.S. Mint, encouraged the development of American manufacturing, and drafted an elaborate system of duties, tariffs, and excises. Within five years, the complete "Hamilton program" had replaced the chaotic financial system of the Confederation era.

Key Terms

- Federalists: Statesmen or public figures who supported ratification of the proposed Constitution of the United States between 1787 and 1789.

- Whiskey Rebellion: An uprising in southwestern Pennsylvania caused by Hamilton's excise tax of 1791.

Hamilton in Brief: Secretary of the Treasury

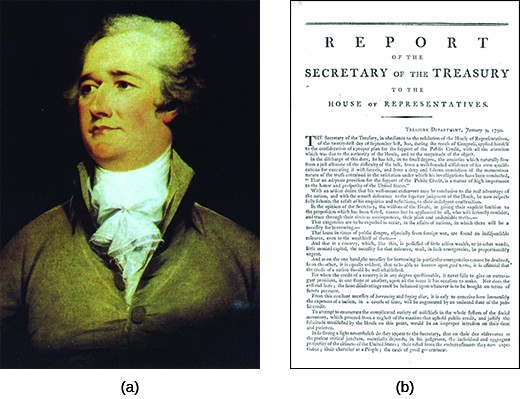

George Washington appointed Alexander Hamilton as the first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury in 1789, a position he held until January 1795. During those five years, much of the structure of the government of the United States was developed, beginning with the function of the executive cabinet itself. According to historian Forrest McDonald, Hamilton saw his office, like that of the British First Lord of the Treasury, as a position from which he would not only direct fiscal policy, but also oversee his cabinet colleagues under the elective reign of George Washington. Washington did indeed request Hamilton's advice and assistance on matters outside the purview of the Treasury Department.In 1789, Congress authorized Hamilton to assess the public debt situation and to submit reports with recommendations for strengthening the government's credit. Within the next two years, Hamilton submitted five influential reports that detailed his economic vision for the United States:

- First Report on the Public Credit

- Operations of the Act Laying Duties on Imports

- Second Report on the Public Credit

- Report on the Establishment of a Mint

- Report on Manufactures

Hamilton's economic policies: As the first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, shown here in a 1792 portrait by John Trumbull, released the “Report on Public Credit” in January 1790.

A Contested Repayment Strategy

In his "Report on Public Credit," Hamilton also made a controversial proposal to streamline debt repayment by assuming state debt into the federal debt, essentially making the federal government responsible for all debt repayment and giving it much more power. With this in mind, Hamilton called the debt "a powerful cement of our Union."Thomas Jefferson (then the Secretary of State) and James Madison vigorously opposed Hamilton's proposals. Some states, such as Jefferson's home state of Virginia, had paid almost half of their war debts, and their federal representatives argued that their taxpayers should not be assessed again to bail out other states. To ground their claims, Jefferson and Madison also argued that the plan passed beyond the scope of federal powers as outlined in the Constitution.

The First National Bank

In Hamilton's "Second Report on the Public Credit," submitted to Congress in 1790, he recommended the chartering of a national bank, modeled on the Bank of England. Hamilton's proposed national bank would function purely as a depository for federal funds, rather than as a lending bank. The money would come from public funds and private investors willing to lend to the federal government. Unlike the Bank of England, the National Bank would be a business on behalf of the federal government that would serve as a depository for collected taxes, making short-term loans to the government to cover real or potential temporary income gaps and serving as a holding site for both incoming and outgoing monies.There was a heated debate between Democratic-Republicans and Federalists over the constitutionality of a National Bank. Jefferson and Madison, leading the opposition, argued that taking the centralization of power away from local banks was dangerous to a sound monetary system and unfairly designed to benefit northern business interests at the expense of southern agricultural development. Furthermore, they contended that the creation of such a bank violated the Constitution, which specifically stated that congress was to regulate weights and measures and issue coined money, rather than mint and bills of credit, and prohibited the chartering of private corporations.

While Democratic-Republicans proclaimed the National Bank unconstitutional, Hamilton, in his Defense of the Constitutionality of the Bank, used a broad interpretation of the Constitution to argue that any congressional actions not specifically prohibited by the Constitution could be employed by Congress to achieve an end for the common good. Later in the Supreme Court case of McCullough v. Madison, this interpretation was described as the "doctrine of implied powers" left ambiguous in the Constitution. After reading Hamilton's defense of the National Bank Act, Washington signed the bill into law.

Other Economic Programs

In his reports, Hamilton also helped draft proposals for the U.S. Mint, encouraged the development of American manufacturing, and drafted an elaborate system of duties, tariffs, and excises. Within five years, the complete "Hamilton program" had replaced the chaotic financial system of the Confederation era with a modern apparatus that gave the new government financial stability and investors sufficient confidence to invest in government bonds.One of the principal sources of revenue that Hamilton recommended Congress should approve was an excise tax on whiskey. Strong opposition to the whiskey tax by cottage producers in the remote, rural regions of western Pennsylvania erupted into the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794. The mainly Scotch-Irish settlers there, for whom whiskey was an important economic commodity, viewed the tax as discriminatory and detrimental to their liberty and economic welfare. After many public protests, rioting broke out in 1794 against the central government's efforts to collect the tax. Troops called out by President Washington quelled the rioting, and resistance evaporated. President Washington pardoned the two rebels who were convicted of treason, and the tax was repealed in 1802.

Promoting Economic Development

In order to foster economic development in a financially shaky new nation, Hamilton stressed the development of manufacturing and commercial interests.Learning Objectives

Describe the financial difficulties confronting the early American republic and the central actions taken by the new federal government in responseKey Takeaways

Key Points

- Hamilton’s financial program helped to rescue the United States from near bankruptcy in the late 1780s and marked the beginning of American capitalism. Hamilton's economic project included several incentives designed to encourage the development of American manufacturing and commerce.

- The "American System" utilized semi-skilled laborers to make standardized, identical, interchangeable parts, which could be assembled quickly and with minimal skill; this system allowed industrialists to greatly reduce costs. Unlike the Democratic- Republicans, who believed that agriculture formed the backbone of the American economy, Hamilton believed that overall commercial development would foster the republican virtues of self-reliance and autonomy, as well as American independence in the world economic system.

- Establishing economic autonomy and free-trade alliances meant that the United States could foster an independent presence in the world economic system and remain unfettered to the interests of other nations in its commercial activity.

- One of the principal sources of revenue that Hamilton recommended Congress approve was an excise tax on whiskey. Strong opposition to the whiskey tax by cottage producers in the remote, rural regions of western Pennsylvania erupted into the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794.

Key Terms

- manufacturing: The transformation of raw materials into finished products, usually on a large scale.

- commerce: The exchange or buying and selling of commodities; especially the exchange of merchandise, on a large scale, between different places or communities; extended trade or traffic.

- autonomy: Self-government; freedom to act or function independently.

Financial Difficulties of a New Nation

The United States was born mired in debt. In 1789, when Alexander Hamilton was appointed as Secretary of the Treasury, the federal debt was more than $53 million, and the states had a combined debt of around $25 million. The United States had been unable to pay its debts in the 1780s and was therefore considered a credit risk by European countries. In his new office, Hamilton wrote a series of reports offering solutions to the economic crisis brought on by these problems. The reports addressed public credit, banking, and raising revenue and encouraged the development of an elaborate system of duties, tariffs, and excises.With the support of Washington, the entire Hamiltonian economic program received the necessary support in Congress to be implemented. In the long run, Hamilton’s financial program helped to rescue the United States from its state of near bankruptcy in the late 1780s. His initiatives marked the beginning of American capitalism, making the republic creditworthy, promoting commerce, and establishing a solid financial foundation for the nation. His policies also facilitated the growth of the stock market, as U.S. citizens bought and sold the federal government’s interest-bearing certificates.

The country's first economic policy: As Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton would propose influential economic policies during Washington's term as President.

Advances in Manufacturing

In the 1790s, Hamilton and the Federalist Party extolled innovation in manufacturing (demonstrated by the development of the "American System") as the supreme virtues of American republicanism. The "American System" featured semi-skilled laborers using machine tools and jigs to make standardized, identical, interchangeable parts, which could be assembled quickly and with minimal skill. Because the parts were interchangeable, it became possible to separate manufacturing from assembly, which then could be carried out by semi-skilled laborers on an assembly line—an example of the division of labor. The system allowed industrialists to greatly reduce costs.In his Report on Manufactures, Hamilton argued that an expansion of manufacturing (particularly of textiles) was necessary in order to produce nationally made finished goods—and thereby reduce American dependence on European products. Arguing that continued dependence on Europe for manufactured goods jeopardized U.S. independence, Hamilton encouraged Congress to implement protective tariffs, invest in new mechanization processes and technical innovations, import foreign technicians and laborers to foster mechanization, and encourage loans for business entrepreneurs.

Furthermore, Hamilton and the Federalists believed that the values of successful industrialists—self-reliance, autonomy, innovation, and entrepreneurship—were the bedrock on which the national political system should be modeled. According to Hamilton, the commercial classes were talented, industrious, and virtuous men who could be trusted to wield federal political power. Hence, for the Federalists, manufacturing was of primary importance to federal policy because it served as a breeding ground for new generations of talented, virtuous republican leaders.

As opposed to his Democratic-Republican contemporaries who espoused agriculture and farming as the backbone of the American economy, Hamilton believed that overall commercial development would foster the republican virtues of self-reliance and autonomy, as well as American independence in the world economic system. Hamilton's distinctive lack of an agricultural policy, in favor of this commercial plan, alienated him from some of his political contemporaries; however, his vision for American manufacturing later influenced the development of the United States' textile industry after the invention of the cotton gin increased American cotton cultivation in the 1800s.

The Whiskey Rebellion

As part of his economic policies designed to address the national debt, Hamilton urged Congress to impose a tax on domestically distilled liquors. He believed this "luxury tax" would not cause much consternation in the American public. However, farmers on the western frontier operated private distilleries to generate extra income, and for many poor farmers, whiskey was a medium of exchange, rather than a source of cash. For these farmers, the whiskey tax constituted an unfair income tax that favored wealthy farmers and eastern distilleries who could afford to pay a flat tax per barrel.In 1794, outbursts of violence against tax assesors in western Pennsylvania evolved into a large mob of poor farmers who, motivated by other economic grievances as well as the whiskey tax, demanded independence from the United States. President Washington sent a militia of more than 12,000 men to subdue the rebellion, which occurred without bloodshed. Washington later pardoned the two rebels who were convicted of treason, and the tax was repealed in 1802.

The Washington administration's suppression of the Whiskey Rebellion was met with widespread popular approval and demonstrated that the new national government had the willingness and ability to suppress violent resistance to its laws. Historians such as Steven Boyd have argued that the suppression of the Whiskey Rebellion prompted anti-Federalist westerners to finally accept the Constitution and to seek change by voting rather than by resisting the government. Federalists, for their part, came to accept that the people could play a greater role in governance.