The myth of Eldorado (or El Dorado: “the golden”) arose following the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus in 1492, as numerous Spanish adventurers and soldiers, the conquistadors, embarked on the conquest of this new continent, drawn by its reputation for immense wealth. This fabulous country, rumored to be brimming with gold in its subsoil, exerted an extraordinary fascination on these men eager to enrich themselves, further reinforced by the magnitude of the spoils obtained by Cortés in Mexico and Pizarro in Peru, which confirmed the belief that this kingdom truly existed.

Gold: An Indispensable Metal

Gold has always played a special role in the history of nations, but its importance has varied over time. Thus, after the fall of the Roman Empire, this metal lost much of its value because the contraction of trade made the use of currency less necessary.

However, the resurgence of commerce in the late Middle Ages, combined with the depletion of traditionally exploited gold mines, once again greatly increased the thirst for gold. The discovery of America in 1492 raised hopes for the emergence of new supply sources for Europe.

Spain, in particular, emerged very impoverished from its struggle against Muslim occupation (Reconquista) and, with ambitious political designs, saw it as an extraordinary opportunity. Therefore, Queen Isabella of Castile and then Charles V endeavored to promote the expeditions of the conquistadors in search of El Dorado.

What Is the Myth of El Dorado?

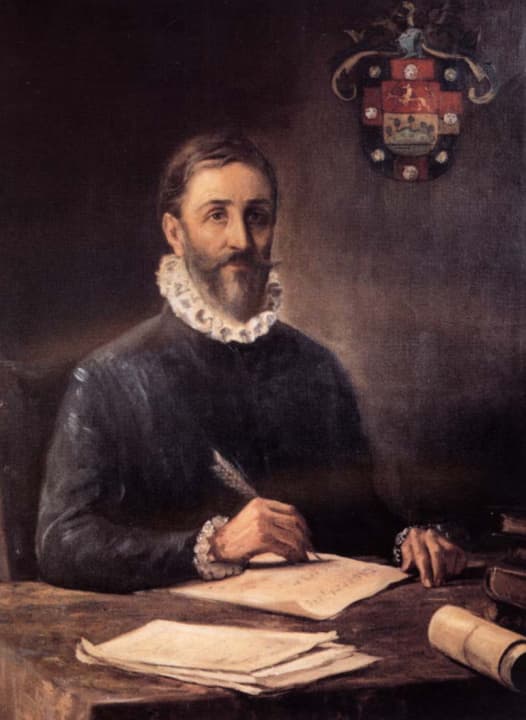

The myth of El Dorado finds its origin in the legend of the “golden man.” The chronicler and historian Gonzalo Fernandez de Oviedo made their first official appearance in 1534. However, for several years before that, the Spanish had been hearing persistent rumors about this kingdom located somewhere inland.

The Chibcha Indians, natives of Cundinamarca, the “land of the Condor” (present-day Colombia), celebrate a strange ceremony every year. During this ceremony, a cacique, or local sovereign, covers himself with turtle grease and gold powder and then advances, sparkling, amidst his subjects, who sing with joy and beat on drums. The king and nobles then board canoes and, in the middle of Lake Guatavita, cast gold and emeralds into the water as offerings to the gods. Finally, the cacique plunges into the lake and reappears amidst thunderous applause.

Thus, the legend of the golden man, El hombre dorado, is born, soon shortened to El Dorado, who is supposed to reign over a fairyland. But over the years, the myth continues to transform, and El Dorado, in one word, becomes the kingdom of gold itself, where streets are paved with nuggets and where houses and objects are covered in precious metal.

The Conquistadores’ Quest

The first to embark on the search for El Dorado was a cruel man, the German Ambroise Alfinger, who financed his expeditions between 1529 and 1538 by selling Indians marked with a red-hot iron as slaves in Santo Domingo. Departing from Coro, the capital of Venezuela, he sailed up the Magdalena River, massacring numerous indigenous tribes along the way in order to crush any sense of rebellion within them. But Alfinger, lost and with his troop decimated, abandoned his quest after several years of unsuccessful efforts, though he was only a few dozen kilometers away from Cundinamarca. He suffered a poisoned arrow wound to the neck during a combat with Indians and passed away shortly after.

This failure did not deter other conquistadors. Only one, however, succeeded: the Spaniard Gonzalo Jimenez de Quesada, a former lawyer enamored with adventures, nicknamed “the knight of El Dorado” by his biographer Germán Arciniegas. After a long and arduous journey during which his men were harassed by Indians and plagued by tropical fevers, he entered Cundinamarca in January 1537 and conquered its capital, Bogotá. Indeed, he found gold and diamonds there, but nothing resembling the inexhaustible reserves that were supposed to be contained in the Kingdom of Gold. This disillusionment convinced the conquistadors that El Dorado lay elsewhere, leading them, albeit in vain, to turn their attention to the eastern part of the continent, to the Orinoco and the Guianas (1559–1569).

Despite the failures, the dream of El Dorado persisted into the 16th century. The marvelous accounts of the English explorer Sir Walter Raleigh contributed to its propagation in the 17th century, and in the 18th century, Voltaire still placed an adventure of Candide there.

Two Centuries of Unsuccessful Expeditions

For over two centuries, the conquistadors embarked on dozens of expeditions, most of which ended in tragedy and bloodshed, but gradually allowed for the exploration and colonization of the northern part of South America. Jorge de Spira reached the foot of the Andes (1535–1538) but had to retreat after losing most of his men to the Indians and exhaustion. Nicolas Ferdermann and Sebastian de Belalcazar, following Gonzalo Jimenez de Quesada, each reached the high plateau of Bogotá (1537–1539), only to encounter the same disappointments as their predecessors.

From 1584 to 1597, the tireless Antonio de Berrio fruitlessly searched for the Manoa lagoon in the Llanos and Guyana. It was believed at the time that this was the location of the mythical kingdom. At the age of sixty, he was even appointed governor of El Dorado and Guyana, but he died fifteen years later without ever finding the kingdom he theoretically governed! Furthermore, repeated attempts to dredge or pump the waters of Lake Guatavita to recover the gold and jewels thrown during ceremonies took place between 1540 and 1912. They consistently yielded almost no results.

The End of the El DoradoMyth

The legend definitively died out in the early 19th century with the German scientist Humboldt. At the request of the Spaniards, who still believed in El Dorado, he explored the valleys of the Apure and Orinoco. His highly precise topographic surveys left no doubt: El Dorado did not exist.

In 1954, Colombian archaeologists established that a meteorite fell thousands of years ago into the waters of Lake Guatavita. The ceremony of the Golden Man perhaps only marked the memory of this event, combined with a tribute to a god believed to have descended to the bottom of the lake. And the Spanish conquerors, at the cost of much suffering, may have been chasing a shooting star that had been extinguished for centuries.