Wattstax

| Wattstax | |

|---|---|

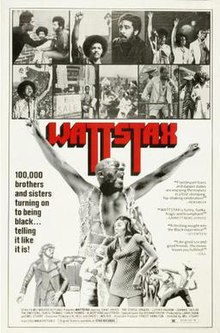

Theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Mel Stuart |

| Produced by | Larry Shaw Mel Stuart |

| Starring | The Staple Singers Richard Pryor Carla Thomas Rufus Thomas Luther Ingram Kim Weston Johnnie Taylor The Bar-Kays Isaac Hayes Albert King |

| Cinematography | John A. Alonzo |

Production companies | Stax Films Wolper Pictures |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 103 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $1,560,000 (rentals)[1] |

Wattstax was a benefit concert organized by Stax Records to commemorate the seventh anniversary of the 1965 riots in the African-American community of Watts, Los Angeles.[2][3] The concert took place at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum on August 20, 1972. The concert's performers included all of Stax's prominent artists at the time. The genres of the songs performed included soul, gospel, R&B, blues, funk, and jazz. Months after the festival, Stax released a double LP of the concert's highlights, Wattstax: The Living Word. The concert was filmed by David L. Wolper's film crew and was made into the 1973 film titled Wattstax. The film was directed by Mel Stuart and nominated for a Golden Globe award for Best Documentary Film in 1974.

In 2020, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Festival production[edit]

Development[edit]

Stax Record's West Coast director, Forrest Hamilton, came up with the idea for the Wattstax concert. Being in Los Angeles during the Watts Riots in 1965, Hamilton later became aware of the yearly Watts Summer Festival that commemorated the revolt.[4]

Hamilton contacted Stax Records' main offices in Memphis, TN and shared his concept of a benefit-concert for the seventh Watts Summer Festival. At first, Stax was not so sure about putting together a small concert, with big stars, for a small community such as Watts. Tommy Jacquette, the founder of the Watts Summer Festival, was contacted about the festival idea. With Jacquette being supportive, the concert idea was slowly developing into something larger.[4]

Stax president Al Bell, who was very involved in planning the concert, decided that if the festival was going to be as big as he imagined, the festival could not just be held at a small park in Watts. It had to be held somewhere like the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. A team of several Stax directors, including Jacquette, contacted the L.A. Coliseum to schedule a meeting. When the meeting took place, the managers at the Coliseum were not convinced that "a little record company" from Memphis could sell enough tickets to fill the stadium.[4]

Marketing[edit]

Stax picked a date—August 20, 1972—which was Isaac Hayes's 30th birthday and a few days after the seventh anniversary of the Watts Riots. The name of the concert—"Wattstax"—was formed to include "Watts", as in the neighborhood, and "Stax", the name of the record company putting the show together. All seats were reserved and priced at only one dollar each, as Stax wanted to make it possible for anyone to attend. Pre-sales were quite successful, easing concerns about the financial viability of the concert.[4]

Construction[edit]

The stage was built the day before the concert, with construction starting in the middle of the night and continuing into the morning. This conflict happened because a football game was scheduled on the night of August 19 between the Oakland Raiders and the Los Angeles Rams, the home team for the Los Angeles Coliseum.[4] Immediately after the football game, trucks full of long wood-planks drove onto the field. The stage was built right in the center of the field and was built high enough where artists could walk/sit under (a little less than 20 feet tall).[4]

A platform was built that led from the road (where artists would walk from) to the side stairs of the stage. The seats were hand-cleaned and trash was picked up all around the Coliseum. Also, due to the Coliseum's policy, there could be no seating on the field to prevent the grass being ruined for the Rams' next game on August 21.[5] During the Wattstax concert in fact, an issue arose when much of the audience poured onto the field to dance while Rufus Thomas performed "Do the Funky Chicken". Stax executive Larry Shaw immediately asked Thomas to get the audience to return to the stands, leading to a memorable moment in the documentary film when one particular straggler refuses to leave and Thomas makes pointed fun of him.[5]

The bleachers were set-up so that there would be more seating that included a better view of the stage, and a fence was built around the stage for the artists' safety. In addition, a large group of African-American policemen from the LAPD were requested to be scattered inside and outside the Coliseum.[6]

The dressing rooms for Stax's artists were outside/behind the stadium, and two vans were rented to drive the artists up to the stage and back to the dressing rooms. Portable restrooms were rented (for the artists to use before and after their sets) and placed right under the side of the stage. Colored stage lighting was hammered onto poles on each corner of the stage. Stacked speakers were placed in each corner of the fenced area. Below the stage, a long table was placed to hold several open reel tape recorders, capturing the concert performances for later release on records.[4]

A film crew, made up of a significant number of African-Americans at Stax's request,[5] was scattered from the top-row of the stadium to the corners of the stage where the artists were zoomed-in-on. The film crew was told to capture the artists singing, but also get shots of the crowd dancing. The attendance of 112,000 was said to be the largest gathering of African-Americans outside of a civil rights event to that date.[4]

Festival[edit]

At around 1:45 p.m., the Coliseum grounds began filling with attendees. Guards stamped tickets and told concertgoers where their seats were located. The stadium's seats filled up quickly, while the production team was making sure everything was ready. The concert's orchestra (dubbed The Wattstax'72 Orchestra) and its composer, Dale Warren, sat until 2:38 p.m. ready to play their warm-up instrumental titled "Salvation Symphony". At 2:38 p.m., the first song was performed to a crowd of 112,000 (mostly African-American).

Performing artists[edit]

- 2:38: "Salvation Symphony" by Dale Warren

- 2:57: "The Star-Spangled Banner" by Kim Weston

- 3:01: Speech by Tommy Jacquette

- 3:05: Speeches by Anonymous Speakers

- 3:13: Introduction/"I Am Somebody" by Jesse Jackson

- 3:19: "Lift Every Voice and Sing" by Kim Weston

- 3:23: Speech and Staple Singers Intro by Melvin Van Peebles and "Heavy Makes You Happy" by The Staple Singers

- 3:27: "Are You Sure" by The Staple Singers

- 3:31: "I Like the Things About Me" by The Staple Singers

- 3:37: "Respect Yourself" by The Staple Singers

- 3:42: "I'll Take You There" by The Staple Singers

- 3:47: "Somebody Bigger Than You and I" by Jimmy Jones

- 3:52: "Precious Lord, Take My Hand" by Deborah Manning

- 3:57: "Better Get A Move On" by Louise McCord

- 4:01: Unknown Performance by Eric Mercury

- 4:04: Unknown Performance by Freddie Robinson

- 4:09: "Them Hot Pants" by Lee Sain

- 4:13: Unknown Performance by Ernie Hines

- 4:17: "Wade in the Water" by Little Sonny

- 4:21: "Pin The Tail on the Donkey" by The Newcomers

- 4:24: "Explain It to Her, Mama" by The Temprees

- 4:27: "I’ve Been Lonely Too Long" by Frederick Knight

- 4:31: "I Forgot to Be Your Lover" by William Bell

- 4:34: "Knock on Wood" by Eddie Floyd

- 4:38: "Old-Time Religion" by The Golden Thirteen: William Bell, Louise McCord, Deborah Manning, Eric Mercury, Freddie Robinson, Lee Sain, Ernie Hines, Little Sonny, The Newcomers, Eddie Floyd, The Temprees, Frederick Knight

- 4:42: "Lying on the Truth" by Rance Allen

- 4:46: "Up Above My Head" by Rance Allen

- 4:50: "Introduction" by David Porter

- 4:54: "Ain't That Loving You (For More Reasons Than One)" by David Porter

- 4:58: "Can't See You When I Want To" by David Porter

- 5:09: "Reach Out and Touch (Somebody's Hand)" by David Porter

- 5:12: "Son of Shaft" by The Bar-Kays

- 5:18: "Feel It" by The Bar-Kays

- 5:23: "In the Hole" by The Bar-Kays

- 5:26: "I Can't Turn You Loose" by The Bar-Kays

- 5:31: Unknown Performances by Tommy Tate

- 5:41: "I Like What You're Doing (To Me)" by Carla Thomas

- 5:46: "Gee Whiz (Look at His Eyes)" by Carla Thomas

- 5:49: "B-A-B-Y" by Carla Thomas

- 5:52: "Pick Up the Pieces" by Carla Thomas

- 5:55: "I Have a God Who Loves" by Carla Thomas

- 6:00: "Matchbox Blues" by Albert King

- 6:05: "Got to Be Some Changes Made" by Albert King

- 6:11: "I'll Play the Blues for You" by Albert King

- 6:17: "Killing Floor" by Albert King

- 6:21: "Angel of Mercy" by Albert King

- 6:26: "The Breakdown" by Rufus Thomas[7]

- 6:32: "Do the Funky Chicken" by Rufus Thomas

- 6:39: "Do the Funky Penguin" by Rufus Thomas

- 6:45: "I Don't Know What This World Is Coming to" by The Soul Children

- 6:52: "Hearsay" by The Soul Children

- 7:00: Speech by Fred Williamson and Jesse Jackson

- 7:03: "(If Loving You Is Wrong) I Don't Want to Be Right" by Luther Ingram

- 7:06: "Theme from Shaft" by Isaac Hayes

- 7:12: "Soulsville" by Isaac Hayes

- 7:17: "Never Can Say Goodbye" by Isaac Hayes

Film production[edit]

The 1973 documentary release of Wattstax includes, in addition to the festival sets by Rufus Thomas, Carla Thomas, the Staples Singers, the Bar-Kays, and many others, musical performances by artists who were unable to perform during the actual Wattstax concert. The Emotions perform the gospel song "Peace Be Still" from the pulpit of the Friendly Will Baptist Church in Watts in a sequence shot several weeks after the Wattstax concert.[8][9] Johnnie Taylor performs his 1971 hit single "Jody's Got Your Girl and Gone" onstage at the Summit Club in Los Angeles in a sequence filmed September 23, 1972.[10] Little Milton performs "Walking the Streets and Crying" in a lip-synced performance staged near train tracks adjacent to the Watts Towers.[11]

Rev. Jesse Jackson, head of Operation PUSH, was the MC of the Wattstax concert.[4] Richard Pryor appears as the host of the film via interstitial stand-up scenes filmed at a bar following the Wattstax concert.[12] Interspersed between the musical performances is documentary footage of the residents of Watts going about their daily lives, local businesses, as well as interview segments with Black Los Angelians. Rather than being fully candid, these segments feature actors discussing predetermined topics.[4] Among these actors is Ted Lange, later one of the stars of the TV series The Love Boat.[13]

Film releases[edit]

As originally edited, the Wattstax film concluded with two performances by Isaac Hayes of hit songs from the motion picture Shaft: "Theme from Shaft" and "Soulsville." Following Wattstax's premiere on February 4, 1973, at the Los Angeles Music Center,[14] but before its wide release in the United States, Stax Films and Wolper Films were informed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), producers and distributors of Shaft, that Wattstax could not be released with Hayes' performance numbers.[15] MGM's contracts for the music in Shaft prevented any use of those songs in any other film until 1978.[15]

As a result, Isaac Hayes was pulled from a tour in the Netherlands to return to Los Angeles and film a new performance number based around his next scheduled single, "Rolling Down a Mountainside."[15] This number concluded the original theatrical release of Wattstax from Columbia Pictures and most subsequent television and home video exhibitions.[15]

Because of profanity used throughout the film's interview segments, Wattstax was rated "R" by the MPAA in the United States, preventing children under 17 from attending the film unaccompanied by an adult. Despite that rating, Stax promoted the film to family audiences, spinning the "R" rating with the promotional tagline "Rated 'R' Because it's Real."[16]

Wattstax was restored and remastered in 2003, using Apple's Final Cut Pro and Cinema Tools to create new film and HD video elements from its original 16 mm film negatives. The original audio elements were used to create a new surround sound soundtrack and new stereo elements for soundtrack album releases.[17] "Theme from Shaft" and "Soulsville" were restored to the film at this time as well.

The restored film first played in limited release in the United States during the summer of 2003.[18] In January 2004, the restored version of the film played at the Sundance Film Festival, followed by a theatrical reissue in June by Sony Pictures Repertory. In September 2004, the PBS series P.O.V. aired a new documentary about the concert and the movie. That same month, the movie was released on DVD by Warner Bros., which obtained the video rights when it purchased the Wolper library (Warner's former sister company, Warner Music Group, coincidentally owns the rights to most pre-1968 Stax recordings).[19] Warner Bros. also acquired the distribution rights from Sony as a result of their ownership of the library of current copyright holder The Saul Zaentz Company.

Album releases[edit]

Stax released Wattstax: The Living Word on January 18, 1973.[20] This double-LP album release included live recordings from the Wattstax concert event, as well as a handful of studio recordings—The Staples Singers' "Oh La Di Da" and Eddie Floyd's "Lay Your Loving on Me"—overdubbed with audience reactions.[21] The Living Word sold over 220,000 copies and a second two-disc release, The Living Word: Wattstax 2, followed later that year.[20] Wattstax 2 featured additional live performances from both the concert and related performances seen in the film, as well as studio tracks by other music artists and Richard Pryor.[22]

Coinciding with the preparation for the 2004 reissue of the film, Stax Records (by this time an imprint of Fantasy Records and later Concord Music Group) released the Wattstax: Music from the Festival and Film three-disc collection, containing remastered versions of live performances from the Wattstax concert and the ancillary Los Angeles shows seen in the film.[23] A 35th-anniversary version was released in 2007.[24]

In 2004, Stax released Wattstax: Highlights from the Soundtrack, a single-disc audio CD featuring only the songs included in the documentary film.[25]

Songs in the film[edit]

In order of appearance:

- "Whatcha See Is Whatcha Get", performed by The Dramatics

- "Oh La De Da", performed by the Staple Singers

- "We the People", performed by The Staple Singers

- "The Star-Spangled Banner", performed by Kim Weston

- "Lift Every Voice and Sing", performed by Kim Weston

- "Someone Greater Than I", performed by Jimmy Jones

- "Lying on the Truth", performed by the Rance Allen Group

- "Peace Be Still", performed by The Emotions

- "Old-Time Religion", performed by The Golden Thirteen: William Bell, Louise McCord, Deborah Manning, Eric Mercury, Freddie Robinson, Lee Sain, Ernie Hines, Little Sonny, The Newcomers, Eddie Floyd, The Temprees, Frederick Knight

- "Respect Yourself", performed by The Staple Singers

- "Son of Shaft/Feel It", performed by The Bar-Kays

- "I'll Play the Blues for You", performed by Albert King

- "Walking the Back Streets and Crying", performed by Little Milton

- "Jody's Got Your Girl and Gone", performed by Johnnie Taylor

- "I May Not Be What You Want", performed by Mel and Tim

- "Pick Up the Pieces", performed by Carla Thomas

- "The Breakdown", performed by Rufus Thomas

- "Do the Funky Chicken", performed by Rufus Thomas

- "(If Loving You Is Wrong) I Don't Want to Be Right", performed by Luther Ingram

- "Theme from Shaft", performed by Isaac Hayes[26]

- "Soulsville", performed by Isaac Hayes[26]

Production credits[edit]

- Directed by: Mel Stuart[27]

- Produced by: Larry Shaw, Mel Stuart

- Executive Producers: Al Bell, David L. Wolper

- Associate Producer: Forest Hamilton, Hnic.

- Consultants: Rev. Jesse Jackson, Tommy Jacquette, Mafundi Institute, Rev. Jesse Boyd, Teddy Stewart, Richard Thomas, John W. Smith, Sylvester Williams, Carol Hall

- Cinematography: Roderick Young, Robert Marks, Jose Mignone, Larry Clark

- Edited by: Robert K. Lambert, David Newhouse, David Blewitt

- Assistant Director: Charles Washburn

- Concert Unit Director; Sid McCoy

- Production Coordinator: David Oyster

- Music Supervisor: Terry Manning

- Music Recording: Wally Heider, Inc.

- Post Production Supervisor: Philly Wylly

- Concert Artist Staging: Melvin Van Peebles

- Music Conductor: Dale Warren

- Lighting: Acey Dcey

- Production Staff: Jim Stewart, Johnny Baylor, Gary Holmes/Mind Benders, Humanities International, Edward Windsor Wright

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1973". Variety, January 9, 1974. pg 60.

- ^ Maycock, James (19 July 2002). "Loud and Proud". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ Kennedy, Gerrick (18 August 2015). "Perspective: Remembering the 1972 Wattstax concert brings us to crucial voices of Kendrick Lamar, Prince". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Gordon, Robert (2015-02-03). Respect Yourself: Stax Records and the Soul Explosion. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 303. ISBN 978-1-60819-416-2.

- ^ a b c Bell, Al (January 10, 2006). Wattstax: Audio commentary with Al Bell, Isaac Hayes, et al (DVD). Burbank, CA: Warner Home Video. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- ^ Bowman, Rob (Historian) (January 10, 2006). Wattstax: Audio commentary with Rob Bowman and Chuck D (DVD). Burbank, CA: Warner Home Video. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (13 June 2003). "Wattstax". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ Bowman, Rob (Historian) (January 10, 2006). Wattstax: Audio commentary with Rob Bowman and Chuck D. (DVD). Burbank, CA: Warner Home Video. Event occurs at 0:25:05-0:26:30. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- ^ Glick, Joshua (2018-01-23). Los Angeles Documentary and the Production of Public History, 1958-1977. Univ of California Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-520-29370-0.

- ^ "Stax Reissues Johnnie Taylor's 'Live at the Summit Club' Album, Recorded in South L.A., at the Time of Wattstax". PRWeb. Retrieved 2020-04-18.

- ^ Lawrence, Novotny (2014-10-24). Documenting the Black Experience: Essays on African American History, Culture and Identity in Nonfiction Films. McFarland. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-7864-7267-3.

- ^ Saul, Scott (2014-08-12). ""What You See Is What You Get": Wattstax, Richard Pryor, and the Secret History of the Black Aesthetic". Post45: Peer Reviewed. Retrieved 2020-04-18.

- ^ "Remembering the 'black Woodstock'". TODAY.com. September 2004. Retrieved 2020-04-18.

- ^ "Wolperized Black-Angled Ballyhoo For 'Wattstax'; Columbia's Angles". Variety. February 7, 1973. p. 5.

- ^ a b c d Bowman, Rob (Historian) (January 10, 2006). Wattstax: Audio commentary with Rob Bowman and Chuck D. (DVD). Burbank, CA: Warner Home Video. Event occurs at 1:31:20 - 1:35:03, 1:36:50 - 1:39:35. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- ^ Lawrence, Novotny (2014-10-24). Documenting the Black Experience: Essays on African American History, Culture and Identity in Nonfiction Films. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-7267-3.

- ^ "Wattstax". Mixonline. 2003-06-01. Retrieved 2020-04-18.

- ^ Howe, Desson (2003-06-06). "It's Back and It's Proud". Washington Post. Retrieved 2020-04-26.

- ^ "Film Description | Wattstax | POV | PBS". 27 September 2004. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ a b Bowman, Rob (2011-08-01). Soulsville, U.S.A.: The Story of Stax Records. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-85712-499-9.

- ^ "Wattstax: The Living Word (Concert Music from the Original Movie Soundtrack)—Various Artists". AllMusic. Retrieved 2020-04-26.

- ^ "Wattstax: The Living Word, Vol. 2—Various Artists". AllMusic. Retrieved 2020-04-26.

- ^ "Various Artists: Wattstax". Pitchfork. Retrieved 2020-04-26.

- ^ Beets, Greg (Dec 14, 2007). "Wattstax: Music from the Wattstax Festival and Film: Wattstax: Music From the Wattstax Festival and Film Album Review". Austin Chronicle. Retrieved 2020-04-26.

- ^ Kubernik, Harvey (2006). Hollywood Shack Job: Rock Music in Film and on Your Screen. UNM Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-8263-3542-5.

- ^ a b "Wattstax". Mixonline. 2003-06-01. Retrieved 2020-04-18.. Save for the version screened at the film's premiere, prints of Wattstax prior to 2004 omit these numbers in favor of Isaac Hayes performing "Rolling Down a Mountainside," a re-shot number added to prevent legal issues with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

- ^ Canby, Vincent (16 February 1973). "Film: 'Wattstax,' Record of Watts Festival Concert". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

External links[edit]

- Official website

- Wattstax at IMDb

- Wattstax at AllMovie

- P.O.V. Wattstax companion Web site (featuring streaming audio of performances and a podcast interview with director Mel Stuart)

- MP3 audio interview with Stax Records expert Rob Bowman on the radio program The Sound of Young America regarding Wattstax

- MSNBC article

- National Review article

- 1973 films

- 1972 in music

- American documentary television films

- Music festivals in Los Angeles

- Concert films

- 1970s English-language films

- POV (TV series) films

- Films directed by Mel Stuart

- 1973 documentary films

- Documentary films about African Americans

- Documentary films about Los Angeles

- Columbia Pictures films

- The Wolper Organization films

- Documentary films about music festivals

- United States National Film Registry films

- Works about soul

- 1970s American films