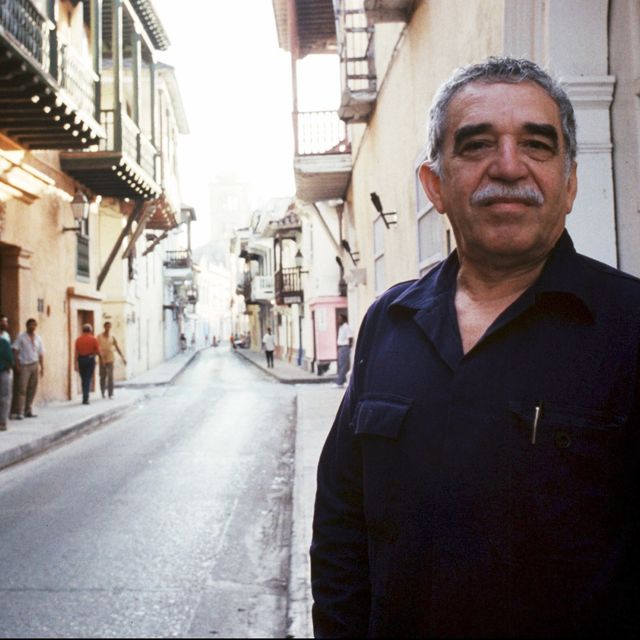

By the mid-1960s, erstwhile journalist Gabriel García Márquez had carved out a respectable professional career in Mexico City after years of itinerancy.

A job writing copy for a prominent advertising agency enabled him to properly care for his wife Mercedes and their two young children. Meanwhile, a successful side career of screenwriting was also bearing fruit, with multiple projects in production.

Yet Gabo, as he was known to friends and family, was profoundly unfulfilled. His four published novels had earned some fans in Spanish-speaking areas of the world but sold modestly. And the story he really wanted to tell, based on his recollections of growing up in the tiny coastal town of Aracataca, Colombia, was still gestating in his mind after two decades of starts and stops.

Fortunately, his luck was about to turn. First came the news that a New York publisher wanted the English-language rights to his four novels. Then came the rush of inspiration that brought about his fifth, One Hundred Years of Solitude (Cien años de Soledad), a work that not only provided the outlet for years of creative frustration but also profoundly impacted the course of Western literature.

García Márquez found himself ready to write en route to a vacation

As told in Gerald Martin's Gabriel Garcia Marquez: A Life, the author's "eureka" moment arrived as he was driving the family to their planned vacation in Acapulco in July 1965 and found himself turning over the line that would soon greet readers at the start of the book:

"Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice."

Depending on the version of this anecdote, García Márquez either immediately drove his family back home to begin writing or spent the vacation scribbling out ideas. Either way, he knew he finally found his way into the story that resisted all previous efforts at being realized.

In addition to the attention-seizing opening came an understanding of how García Márquez would finally present a narrative in which legend and fantasy fused with the mundane details of everyday life. For this, Gabo built on the techniques employed in his time- and narrative-shifting first novel, Leaf Storm (La hojarasca), resulting in a style now known as magical realism. The genre is a predominantly Latin American branch of fiction that incorporates mythical elements into seemingly realistic fiction.

He also found the voice in his head that became the conduit for the tone he was trying to capture. "I remembered that my grandmother used to tell me the most atrocious things without getting all worked up as if she'd just seen them," García Márquez told the Spanish publication Triunfo. "I then realized that that imperturbability and that richness of imagery with which my grandma told stories was what gave verisimilitude to mine. ... How was I going to make my readers believe it? By using my grandmother's same methods."

García Márquez used childhood memories for inspiration

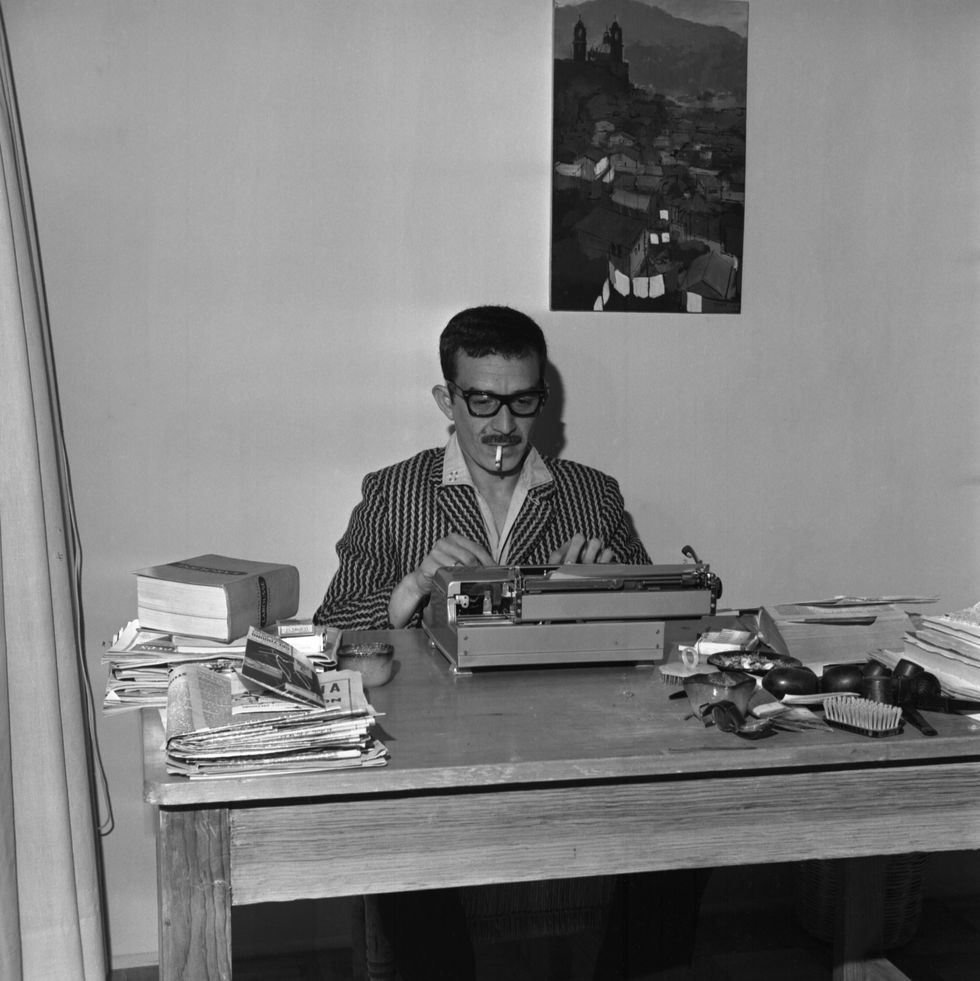

Holed up in his eight-by-ten-foot writer's room, dubbed "the Cave of the Mafia," García Márquez began pounding out his tale on an Olivetti typewriter. He quit his day job with the ad agency in September and built his writing schedule around the window when his children were at school.

Soon, the story about seven generations of the Buendía family in the idyllic-turned-decrepit hamlet of Macondo took shape around fantasy-imbued memories of the author's childhood. Some, like the banana-workers strike, which took place around the year García Márquez was born, became key plot points in the novel. Others, such as a local priest who supposedly levitated, joined a cast of characters who enriched the story with their surreal qualities.

García Márquez also wove in versions of his grandparents, his wife, his friends and even himself—in both Aureliano Buendía and the gypsy leader Melquíades—but never a direct replica of any one person. "All my characters are composites of people I've known," he told Playboy in 1982.

Even if his loved ones weren't fully represented, Gabo poured enough feeling into his creations that he found them difficult to kill off. Both Buendía matriarch Úrsula Iguarán and mistress Pilar Ternera hang on through the story for more than 100 years. And after he finally wrote out the (non-firing squad) death of Aureliano Buendía, the emotionally exhausted author crawled into bed and cried for two hours.

He incurred major debts while devoting time to the book

From the very beginning of his ambitious effort, García Márquez benefitted from a support system of friends who provided crucial feedback. As described in A Life, he would write all morning into the afternoon, dig into his reference books to check some of his facts and then share his day's work with a trusted circle of confidants.

Other friends helped drum up interest in the latest work of this still largely unknown writer. Mexican novelist Carlos Fuentes, a prominent figure in Latin American literature, passed along glowing reviews of the work in progress and saw to it that completed chapters were published in magazines.

Still, despite all the encouragement to continue with his opus, García Márquez took a major risk by pressing forward with no source of income to support his wife and two children. They sold the family car, and when that cash ran dry, Mercedes began beating a regular path to the pawnshop with the TV, radio and jewelry. Somehow, she convinced their butcher to sell them meat on an ever-extending line of credit and the landlord to forego collecting rent for several months.

By this point, García Márquez had generated enough momentum that he was able to ignore these outside pressures and even inject a few inside jokes for his reader friends as the novel reached its conclusion. The title also came to him around this point, as he calculated that approximately 143 years had passed in the story.

By the time he finished One Hundred Years of Solitude in August 1966, García Márquez was 120,000 pesos ($10,000) in debt. He didn't even have enough money to mail the manuscript to the Argentine publishing house Editorial Sudamericana, so he initially sent out half of the pages and returned to the post office after one more trip to the pawnshop. Afterward, Mercedes reportedly quipped, "Hey, Gabo, all we need now is for the book to be no good."

His efforts were validated when the book became a best-seller

Feeling the weight of a year spent without a steady paycheck, García Márquez rejected the opportunity to take a breather and rededicated himself to scriptwriting. Uncertain about the fate of his completed work, he replied to a friend’s inquiry about the book with "I've either got a novel or just a kilo of paper, I’m still not sure which."

All the same, there was a small part of the author that believed he had delivered a critical hit and possibly something monumental about the Latin American spirit. After receiving confirmation of the manuscript’s receipt, he threw out all notes and documentation related to its creation, as part of a preemptive effort to keep prying eyes from looking too closely into his bag of tricks.

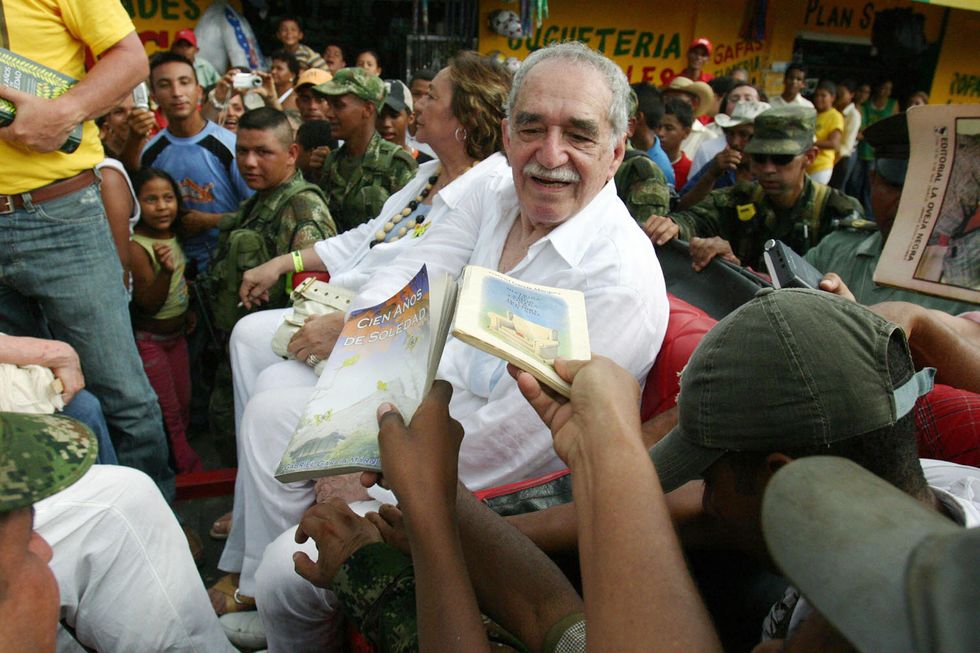

It turned out that instinct was partially correct, though One Hundred Years of Solitude became bigger than even Gabo's expansive imagination could have conceived. Released to a highly receptive South American audience in 1967, the book sold some 50 million copies across nearly four dozen languages, paving the way for García Márquez’s recognition as a literary icon and a Nobel Prize recipient.

Before all the accolades, however, Gabo could finally enjoy the fulfillment that came with achieving his dreams as a novelist. All it took was a lifetime spent reflecting on his formative years, the development of a style to match the magic he remembered from his youth and the devotion of the friends and family who helped carry his vision across the finish line.