By Blaine Taylor

In his 1969 memoir, Albert Speer asserted that Adolf Hitler would never have appointed him Third Reich minister of armaments had not his predecessor in that post, acclaimed engineering genius Dr. Fritz Todt, been killed in a still unexplained airplane crash in early 1942.

Indeed, that was the universally and historically accepted version of this event until 1982, four decades later, when young German postwar historian Dr. Matthias Schmidt began questioning Speer’s motives a year after that top Nazi’s own death in London in the company of a woman who was not his wife.

Ostensibly, the night before his sudden death Dr. Todt had a furious argument with Hitler at the latter’s Eastern Front military headquarters at Wolf’s Lair, Rastenburg, East Prussia.

The contested topic reportedly was the engineer’s bold assertion to his Führer that the war could no longer be won now that the Third Reich was fighting the world’s greatest land power in the Soviet Union, its best sea force in the British Royal Navy, and the globe’s mightiest heavy industrial nation in the United States.

Dr. Speer was already there, waiting in the wings, having made his first trip to Wolf’s Lair that very day, perhaps even for the purpose of succeeding Dr. Todt.

That night, Drs. Todt and Speer agreed to fly back together to Berlin the next morning, but Speer decided instead to sleep in and cancelled. Shortly after takeoff, Todt’s Heinkel He-111 plane blew up in mid-air and crashed on the Rangsdorf airfield near Rastenburg on February 8, 1942. All aboard were killed in a fiery blaze.

Immediately and ever since, dark suspicions of an assassination plot centered on Hitler and the main trio of Todt’s rivals for power within the Nazi German state, Reich Marshal Hermann Göring, Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler, and even Speer himself, then Hitler’s architect and general building inspector for Berlin.

As for the latter suspect, members of the slain Dr. Todt’s family alleged that Speer was capable of anything.

According to Speer in his memoirs, as Göring hurried to Rastenburg allegedly to induce his Führer to appoint him to succeed Dr. Todt, Hitler instead suddenly and surprisingly named Speer to all of Todt’s many offices. The portly Göring was checkmated in another round of Nazi insider power politics.

Hitler may have been keeping Speer in reserve for just such an opportunity. Hitler was also just beginning to realize that the arms industry was not producing as much as needed in the third year of an ever-expanding global war.

Thus, Speer’s presence at Wolf’s Lair proved to be very propitious.

But just who was Dr. Fritz Todt, and why was his loss so lamented by his brother Nazis, at least publicly?

Organization Todt: The Nazi’s Construction Unit

The master builder of the Third Reich, Todt was Nazism’s engineer supreme, the man who erected the much acclaimed Autobahn prior to the war, the East Wall facing Russia, and the vaunted Siegfried Line in the West, as well as the startup of the Atlantic Wall opposite Great Britain across the English Channel. Finally, he served as the first minister of the German armaments industry, upon which Hitler depended to win the war.

The Nazis were fond of naming important groups after their top leaders, such as Organization Todt and its derivatives. Its members wore a brown Nazi Party uniform with a yellow armband on the left with its name lettered in black Germanic runes: ORG. TODT (OT).

Established in 1933 as the Nazis’ construction unit, OT became especially active in the wartime occupied territories, used mainly for rebuilding roads, bridges, and railway lines destroyed in the fighting.

Although commanded first by Todt and then by Speer, OT was ultimately placed under the overall aegis of the armed forces’ engineering command in a typical Third Reich division of authority.

In addition to its native German members, OT ultimately included thousands of POWs, foreign civilian slave laborers, and even Jews. More than 1.4 million men built above-ground bunkers and bridges, and had Todt survived the war he might well have been indicted by the Allies as a war criminal, as was his successor, Speer.

A highly specialized unit independent of the Nazi Party’s own bureaucracy, OT carried out the most impressive construction program since the Roman Empire. By 1945, up to 80 percent of its membership was non-German.

Like Speer later, Dr. Todt worked well with other Nazi organizations such as Dr. Robert Ley’s German Labor Front, the DAF, and Konstantin Hierl’s Reich Labor Service, the RAD.

In the Balkans, OT mined ores essential to the war effort and built roads in Greece and Yugoslavia. It constructed concrete and bomb-proof U-boat pens on the French coast, airfields to the far north to bomb Allied Murmansk convoys, and the Atlantic Wall to defeat the projected Allied cross-Channel invasion.

In the east, OT took part in the thinly disguised “anti-Partisan” combat operations that really meant killing Russian civilians and Jews. Fully armed as a military unit in 1944 and newly named the OT Front, it contained construction worker, administration, works direction, signals, medical, propaganda, and even musical, sections.

OT also built all of Hitler’s many headquarters across Nazi-occupied Europe. Like all other Nazi organizations, OT had regional headquarters as well, at Berlin, Kiev, Belgrade, Paris, and Oslo, plus Rastenburg, Essen, Weimar, Heidelberg, Munich, Villack, and Prague.

After the war, the Allies disbanded OT, thus dashing Dr. Speer’s hope to use it to rebuild the new West Germany from scratch.

An Early Member of the Nazi Party

Friedrich “Fritz” Todt was born at Pforzheim, Baden, Germany, on September 14, 1891, the son of a jewelry factory owner. After the completion of his secondary education, young Fritz continued his studies at Munich’s College of Technology from 1911 to 1914, and again during 1918-1920 at Karlsruhe.

Todt served in World War I, starting as an infantryman with two years on the Western Front from 1914 to 1916. Awarded the Iron Cross for bravery in action, Lieutenant Todt then became an aerial observer directing ground artillery fire for the German Army and was wounded in air combat.

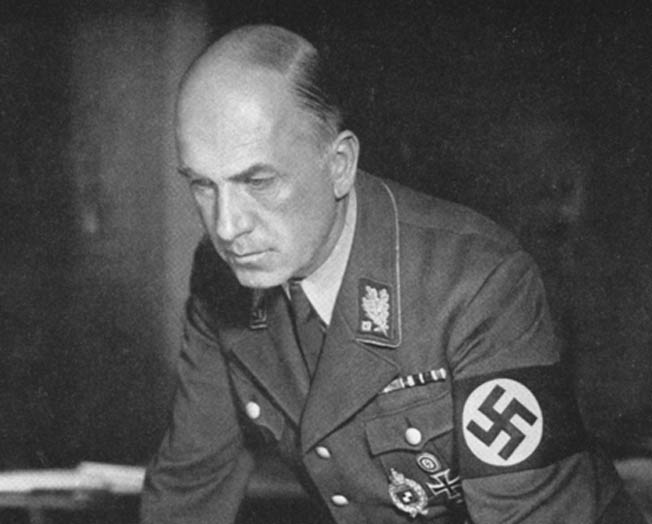

Upon graduation from technical college in 1920, Todt worked as a construction engineer for the firm of Sager & Worner, writing his doctoral dissertation on concrete roadway surfaces and being awarded his doctorate in 1931. Combat veteran Todt joined the Nazi Party on January 5, 1922, and by 1931 was an SS colonel on Himmler’s staff.

Constructing the Führer’s Roads

In 1933, Hitler, upon his appointment as reich chancellor, placed Dr. Todt as head of the government’s construction group that later bore the engineer’s own name. Dr. Todt’s official title was Inspector General of the German Road and Highway System—later known as the Führer’s Roads, the world famous Autobahn, which Hitler commissioned him to build in 1933.

Begun during the last years of the reign of German Kaiser Wilhelm II, the roads were continued in 1921 with the debut of the privately funded AVUS experimental racing circuit. Initially, Hitler opposed the building of the new roads as a means of denying any credit to the hated Weimar regime, but once in office, he swiftly claimed the entire project as his own idea.

Dr. Todt began with 30,000 workers, and soon this figure was more than doubled. Hitler’s stated goal was an ultra-modern network of 7,300 miles of four-lane highways, and a quarter of this was completed by 1938. Even now, many older Germans still recall Hitler as “the man who built the Autobahns.”

The first gala groundbreaking occurred at Frankfurt on September 23, 1933, the initial stretch to Darmstadt being duly opened to the public on May 19, 1935. The first 1,000 kilometers of the Autobahn were completed by September 27, 1936; the second such benchmark was achieved by December 17, 1937; and the third and final 1,000 kilometers by December 15, 1938.

Militarily, Dr. Todt’s motorways could transport 300,000 troops from the eastern border of the Reich to its western frontier in two days of hard driving. From 1935 to 1939, Dr. Todt’s Autobahn facilitated Hitler’s bloodless occupations of the Saar, the Rhineland, Austria, the Sudetenland, and the Czech capital of Prague, as well as the overt invasion of Poland in 1939 and of Western Europe the following year.

World War II was in its second year when Chancellor Hitler named Dr. Todt as inspector general for roads, water, and power, thus increasing his influence. He later added the Head Office for Technology to his growing list of governmental portfolios. By the time Hitler invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, Dr. Todt was also responsible for road building in all the territories occupied by the Germans, stretching from the northernmost tip of Norway to southern France.

Todt was thus in charge of all civil and military engineering for Nazi Europe. This included electrical and mechanical units, port operations, and naval U-boat bunker pen construction on the Continent’s Atlantic coastline.

Building Up Fortress Europe

During the last four months of his life, Dr. Todt found an ever-increasing amount of his time occupied with new road building in the vast regions of the Soviet Union to the far-off Ural Mountains, the expected final eastern expansion of Hitler’s new Nazi empire.

Dr. Todt had built Nazi Germany’s Siegfried Line facing the French Maginot Line during 1938-1939, and he supervised the construction during 1935-1942 of the lesser known East Wall. The East Wall included a trio of lines, the Oder-Warthe Bend, the Pomeranian Line, and the Oder Line, stretching along the eastern German provinces of Pomerania and Silesia.

On both projects, Dr. Todt’s OT worked with the Army’s own elite Fortress Engineering Corps. In November 1939, Hermann Göring, in his capacity as chief of the Nazi economic Four-Year Plan (1936-1940), named Dr. Todt to take overall responsibility for the entire construction sector of the Third Reich proper and its conquered Polish lands.

He faced yet another formidable task, the startup of Hitler’s projected Fortress Europe, the outer shell of which was to be the “impregnable” Atlantic Wall barring a Western Allied seaborne invasion of Nazi Europe. Beginning in 1942, a popular Nazi slogan trumpeted, “The West Wall shields the Reich, while the Second Wall protects Europe!” On December 12, 1941, Hitler gave the new Atlantic Wall the highest construction priority. It became equivalent to 51/2 Hoover Dams and was the largest construction project of the entire war, with 1.5 million tons of steel, enough for 57 Chrysler Buildings.

By D-Day in 1944, there were half a million people from the OT working on the Atlantic Wall. “I needed a job,” stated one. “Those Germans were expert with concrete—I take my hat off to them!” By June 6, 1944, more than 8,500 bunkers had been both designed and built by the OT.

The Atlantic Wall was designed by Dr. Todt during December 1941-February 1942, but was built mainly by his successor, Speer, during 1942-1943, and then improved upon by Field Marshal Erwin Rommel in December 1943-June 1944. Despite all this, however, the fact remains that the Allies breached it in a single day in Normandy, June 6, 1944, because it was strong in line, but nowhere in depth. Via Nazi propaganda, however, the 1942 “Front by the Sea” morphed in the public imagination into the mighty Atlantic Wall.

Engineering Germany’s Armaments Production “Miracle”

By early 1940, Hitler was dissatisfied with the Army’s direction of German wartime weaponry production, and so on March 21, 1940, the Führer named trusty paladin Dr. Todt as the Reich’s first civilian minister for armaments and munitions. Despite his best efforts at reform, though, on December 3, 1941, Minister Todt told Hitler that 60 arms experts had warned him that the overall war economy was at the breaking point.

On March 24, 1940, Dr. Todt told the head of the Army Weapons Office, General Georg Thomas, “From 1941 on, time works against us,” in regard to the overwhelming U.S. industrial potential.

Another problem was that the industrial war effort was dominated by two segments only, aircraft and ammunition, and these claimed more than two-thirds of all German resources. Indeed, as of April 1940, there was even an ammunition supply crisis, just as Nazi Germany was invading Norway and Denmark.

Dr. Todt began reorganizing German armament production and munitions supply, planning to replace the Nazi bureaucracy overseeing them with a permanent industrial council. In effect, this would return them to private business concerns and responsibility. His proposed reforms included greater self-regulation by industry, modifying the harsh system of price controls, a better distribution of government procurement contracts, and an overhaul of the raw materials rationing system among the four competing armed services. These now also included Himmler’s new Waffen SS. A regional ammunition committee was established as well.

In the future, the Army procurement offices would issue orders directly to these committees, with German industrialists themselves taking responsibility. This, in effect, was the very same “self-responsibility of industry” for which Speer was later given full credit, resulting in the 1942-1944 German armaments production “miracle.”

An Aerial Accident or an Assassination?

As for Dr. Todt’s sudden and violent death on February 8, 1942, if not an outright, covert assassination how can the mysterious explosion be explained? The answer may have been provided by Hitler’s personal pilot, SS Lt. Col. Hans Baur, who noted in his postwar memoirs that eyewitnesses to the crash recalled seeing a blue jet of flame exiting from the rear of the aircraft. Like all German military airplanes during the war, the He-111 had a kilogram of dynamite stowed beneath the pilot’s seat that was set off by a tiny looped pull string.

Dr. Todt’s normal place during his aerial trips was in the cockpit next to the pilot. Baur theorized that in squeezing his way into the small cabin and into his passenger’s seat, Todt may have accidentally caught the loop of this pull cord on a side button of his boot, activating both the box’s timer and detonator.

When this fatal sequence of events was noticed, Todt’s plane had been airborne about two minutes, beginning a macabre death race to disarm the explosive device, known as a “destroyer.” The aircraft had reached only the end of airfield tarmac when it exploded, with the plane flipping over at a 30-meter altitude and crashing to earth.

Dr. Todt’s charred body was duly identified when pulled from the grisly wreckage. Baur concludes, probably correctly that there was no plot, only an aerial accident, pure and simple.

Ironically, however, the official Luftwaffe accident report of March 8, 1943, was never published. It is missing, and the enduring mystery continues.

I don’t remember where I heard it first but todts son initiated a investigation into his father’s plane crash which is quite extraordinary considering hitlers personality.