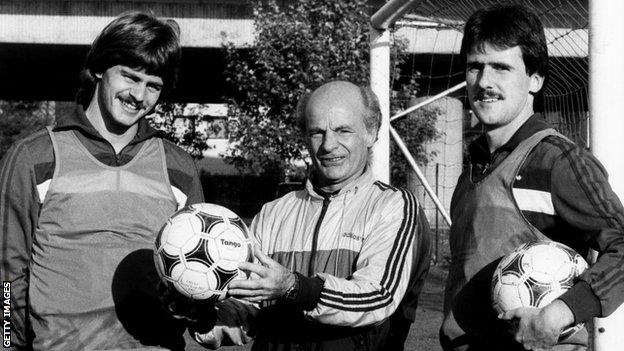

Dirk Schlegel and Falko Götz: The East Berlin footballers who fled from the Stasi

Last updated on .From the section European Football

Dirk Schlegel and Falko Götz had been friends for years by the time they decided to risk everything.

They had grown up together, two football-obsessed kids from the same side of a divided Berlin. They lived close to the wall that had defined their city since it was built in 1961. Their world as children was divided into good and bad, west and east, capitalist imperialism and communist utopia. They both knew not to mention the western TV they secretly watched at home.

Schlegel and Götz rose through the same Dynamo Berlin youth teams. They were part of a sporting organisation embraced tightly by the Stasi - East Germany's brutal and invasive secret police. Erich Mielke, the infamous Stasi leader, was Dynamo's honorary president.

The two players had something else in common. In the eyes of the state, neither could be fully be trusted.

"We both had problems with the authorities and with Dynamo because our history was the same," Schlegel says.

"He had family in West Germany and I had an aunt in England. That kind of thing was not good for our future. There was suspicion. But it was better for our friendship."

Götz made his senior debut for Dynamo in 1979, at the age of 17. Schlegel made his two years later, aged 20.

The two friends broke into their country's strongest team, despite difficult years in the youth academy. They say they were often wilfully overlooked, and their parents were told it would not be correct politically to see them rewarded - not with their background.

But their talent was impossible to ignore. As they developed, both players also began to appear for East Germany's national youth teams. As athletes, they were part of a very select number of citizens who travelled abroad - always under close scrutiny.

The Stasi monitored every aspect of East German daily life, gathering intelligence through a network of informers - and informers who informed on the informers. Some estimates suggest it employed one in every 63 of the population. The structure was sophisticated, bold, all-powerful. The purpose was to keep order: to further the Communist cause. Football also played its role.

Mielke believed Dynamo should become the most successful side in East Germany. They won the league a record 10 consecutive times between 1979 and 1988. There were often accusations of officials giving them preferential treatment, and - as Schlegel recalls - opposition fans hugely resented their victories.

While playing for East Germany's Under-21s in Sweden, Götz began to seriously consider an alternative.

"As I started to play regularly for Dynamo's first team, and internationally too, I began to understand more about what a career in football could mean," he says.

"I had to then ask myself the question: Where do I want it to take me? Do I want to play all the time in East Germany with a club that doesn't offer the best treatment? That from one day to the next could say, 'thank you but now because of who you are, football stops'?"

Schlegel was having similar thoughts, brought to a head by the experience of playing abroad in May 1982 at a youth competition in France.

By the summer of 1983, the friends had decided. They had to get out of East Germany. And they had a plan. But they would have to be careful.

You couldn't just talk anywhere, not about something like this. Schlegel and Götz did a lot of walking - just the two of them. They would go off for hours in the forest. It was the only safe place.

"We discussed it," says Schlegel. "Could we do this big thing? It was not so easy.

"We had to think about the Stasi and the other people in our club. It was a big secret for me and Falko - no-one else."

As champions of East Germany, Dynamo would qualify each year for the European Cup. In those days, the competition featured a straight knockout format - home and away in each round. The best Dynamo achieved was reaching the quarter-finals in 1980, when they lost to eventual winners Nottingham Forest.

The first idea was to try to escape wherever the competition might take them that season - 1983-84. The draw was kind.

In the first round came Jeunesse Esch - champions of Luxembourg. It was an easy tie that would guarantee another chance to escape if the opportunity didn't present itself. And they had a friend who they thought might be able to help.

The first leg was at home. Götz opened the scoring in a 4-1 victory. The second leg was on 28 September 1983.

Their friend had recently been granted permission to move to West Germany - there was an official process by which it was difficult, but not impossible, to legally emigrate - and was living close to the border with Luxembourg.

They had considered the possibility of getting him to meet them and whisk them away in his car, but the timing was off. The friend wouldn't be able to help - he still hadn't received his full identification papers and so couldn't travel across the border into Luxembourg from his new home in West Germany.

Still, Götz and Schlegel thought there might be a chance.

In private, Götz told his father about their intentions. All he said was there was a possibility he would be leaving for good - sometime soon. He was 21 at the time. Schlegel, then aged 22, did not say a word to anyone - not even his mum and dad.

The match was played in Esch-sur-Alzette, right on the border with France. Belgium was only another 10km to the west and West Germany about half an hour's drive to the east. Götz and Schlegel were on the lookout for anything they could take advantage of. Any moment of quiet or confusion that might allow them to slip away.

"It just wasn't possible," Schlegel says. "We had no opportunity at all.

"Everywhere we went - to the hotel, to lunch, to training, to the stadium - we were all together, accompanied by a lot of our 'friends' from the Stasi. We had even flown there in Erich Mielke's private plane. It wasn't an ordinary tourist trip. It was simply too dangerous for us."

Dynamo won 2-0, and the players returned to Berlin. Just days after discussing the possibility of not seeing him again, Götz's father welcomed his son home.

They would have another chance very soon.

Dynamo were next drawn against Partizan Belgrade - the champions of what was then Yugoslavia. This was even better.

In Luxembourg security was tight, but this would be different. Yugoslavia was a fellow Communist country, though not in the Eastern Bloc of states officially allied with the Soviet Union, like East Germany. Surely it would be considered low risk?

Again, Dynamo were at home in the first leg. Again, Götz scored the opener - in the first minute. It finished 2-0 to the East Germans. Bring on the return fixture - in Belgrade.

At about midday on the day of the match - 2 November 1983 - the team travelled together by bus into the centre of Yugoslavia's capital city.

As they pulled up, a member of Dynamo's staff rose out of his seat and told the players: "You have one hour free time. We meet back here at 13:00."

Schlegel and Götz were sitting on opposite sides of the bus.

"We didn't talk; we only looked each other in the eyes," says Schlegel. "We realised it was the moment. And we knew how dangerous it was going to be."

As their team-mates filed off, Schlegel and Götz had still not spoken. They said nothing of the risk they were taking, nothing of the gravity of this one pivotal moment in a life's course.

"I remember we were angry about all the moments we'd already tried to get away but couldn't," Götz says. "On the first day after training it was too risky, the same thing next morning after breakfast. There were too many people around.

"But now in these few seconds we were totally clear on what had to happen. We had everything in our pockets. Papers, a little money. One view of it was enough - this was our chance. Now or never."

The clock was ticking. The rest of the Dynamo squad wanted to spend the hour shopping. Götz and Schlegel tagged along. Their first stop was a record store close by.

As the two went in, Götz spotted something to the side of the building - a slightly hidden entrance and exit, separate to where they had come in. He and Schlegel gave nothing away.

"We tried to stay very close to each other," Götz says. "All the guys around us were buying used records for their families.

"The one special moment was when we saw the door. We saw there was a way you can get out of the shop without anybody noticing. When the time was right, that's when we said: 'Let's go.'"

They steadily peeled away from the larger group. They made sure they weren't being watched. They moved to the door, then went through it. And ran.

"Once we'd made it outside, you're not really thinking about anything," Götz says. "We were only thinking about running. To quickly get as far away from our team as possible.

"We ran for about five minutes in one direction. Then we saw a taxi. We got in but then there was a panic because he didn't want to take us to the West German embassy.

"We had to hail a second cab. As we got in I gave the driver 10 Deutschmarks. He must have driven us about one kilometre - it probably would have been easier to go by foot.

"We looked back to see if anyone had followed us. We couldn't see anybody."

Half an hour earlier, they had been sitting with their team-mates. Now they were inside the West German embassy, talking to staff about what they should do next.

"We were incredibly nervous," says Schlegel. "It was just very incredible what we'd done. Suddenly we were discussing a plan to get us out of Yugoslavia and into West Germany. We were coming up with a schedule for our lives."

The plan began to take shape. First they would be driven to Zagreb, about four hours away. The embassy staff thought it best to get them out of the building - and out of Belgrade - as quickly as possible. The embassy would be the first place the authorities would come looking.

As their car emerged from the underground car park, the players were sitting in the back seats.

"On the way, the deepest thinking was only about surviving this situation," says Götz.

"You are afraid something might happen because you made the first step in a big story. That is why the biggest emotion is just to live through it. That you can do it, you have to do it. Because in something like this, when the end is not good you will have a lot of trouble. A lot of trouble."

In Zagreb, the plan was finalised. At the West German consulate there, Götz and Schlegel were given false papers - two new West German identities to help get them out of Yugoslavia.

Staff told them that driving out, across the Yugoslav border with Austria, would normally cause no issues. But things were a little different that week, they said, and it wasn't totally safe. The pair never got a full explanation but it was decided it would be best to go by train. They were to say they had been on holiday, had lost their passports and had to get new ones, and were on their way 'home' to Munich.

The advice was to travel on the night train from Ljubljana. It would leave at midnight, and they should arrive as close to departure as possible. It was now about 6pm - they had been on the run for six hours.

They were given some food. The staff seemed relaxed - this had been done before, and they were calm and confident of the plan's success. To some extent, this succeeded in soothing the pair's worries. But still, the level of danger they faced was hard to ignore.

Back in Berlin, Götz's father tuned in to watch Partizan v Dynamo. The broadcast began at 7pm. Kick-off was 8pm. His son wasn't in the starting XI. Strange - he was one of their best players. Schlegel was missing too, and neither were even on the bench. No explanation was given, but he knew. It must have happened. Had they been successful? Or had they been caught?

There was one final hurdle to clear.

Schlegel and Götz were driven to Ljubljana. They arrived at the station just before their train was set to depart, tickets in hand, the owners of new identities. Schlegel's name was Norman Meier. Götz can't recall who he was supposed to be.

The train set off. There were about 30 kilometres to cover before it would arrive at the border and Yugoslav customs.

Then the train halted.

In the half light, sitting up in their sleeping compartment, the pair could hear the taps on doors.

They could hear the approaching sound of heavy boots, the guard dogs panting and the jangle of their chains.

"We were both so incredibly nervous but the policeman looked at our documents and said 'OK, fine' and left. It was maybe 20 seconds," Götz says.

"It was so easy. It was nothing.

"For the whole day, we had existed in this state of high tension, where in your mind you are always worried.

"We didn't know what we had started. We didn't know what kind of dangers we might face. But when we got past the Austrian side and the train hadn't been stopped to get the two footballers off, we knew we were safe.

"I think we arrived in Munich at about 6am. I can't believe it today, but we even slept a couple of hours."

In the newspaper stands around the station that morning, their names were already in the press. The headlines read: 'East German players escape to West.'

But the story wasn't quite over. There would be consequences.

The West German diplomatic staff who arranged their false papers had given Schlegel and Götz instructions on what to do. They were to travel to Giessen, where there was a facility that processed refugees.

They arrived late in the afternoon. It was about 7pm by the time either could make a phone call home. Schlegel rang his mum.

"She was a little bit worried," he says.

"It was a big surprise. She knew nothing of our plans but she had heard about our escape from reports on West German TV. I said it was all OK, that I was safe and that was it. We knew the Stasi would be listening."

Götz also rang home.

"My parents directly gave me word to say they were not alone," he says.

"It was: 'OK fine, you are OK, good, we talk later.' Because when something like this happens, you know the authorities are in reaction mode."

Both players realised they would have to be very careful.

"When a player from Dynamo Berlin leaves the club, he is not a good boy," Schlegel says.

"Falko and I had decided that in all interviews we should not talk at all about politics, not about any criticisms of the East, to only talk about football. It would not have been safe - for us or our families.

"We knew that the Stasi also have a lot of people in the West too. That there were people watching us. Spies."

Götz and Schlegel called upon Jorg Berger, a former East Germany youth coach who had fled to the west in 1979.

Berger helped arrange contact with prospective new clubs. They chose to sign for Bayer Leverkusen, but would have to wait a year to make their debuts - Dynamo Berlin would not acknowledge the move. Fifa's 12-month playing ban was seen as a compromise to smooth over their illegal transfer.

At the time, Berger was manager of KSV Hessen Kassel, then in the West German second tier. Before he died in 2010 at the age of 65 after suffering from cancer, he wrote an autobiography in which he claimed he was targeted for assassination in the 1980s, that he was poisoned by a Stasi agent.

Berger also spoke several times about Lutz Eigendorf, a former Dynamo player who defected to the west on the way back from a match in Kaiserslautern in 1979. He had been especially vocal in his criticisms of East Germany after defection.

In March 1983, eight months before Schlegel and Götz arrived secretly in Munich, Eigendorf died in a car crash. Berger believed the accident showed the signs of a Stasi operation - where the driver of a vehicle would be blinded by a bright light while driving at high speed. Tests showed alcohol in Eigendorf's blood, but his friends said he had not been drinking before getting into his car.

Götz and Schlegel had made it to the Bundesliga. They trained with Leverkusen, they settled into their new surroundings, but their old lives were never far behind. They were being watched very closely.

"That's why the Stasi was so famous - for what they did," says Götz.

"They watched us in Leverkusen, and they followed my parents all day long. Not in secret, they wanted them to see. There were interviews, interrogations, pressure. When I was able to access my files at the Stasi archives, when they were made available after German reunification, I found things that I would now rather not talk about.

"But for me at that time, it was important not to say that everything in East Germany is bad, that communists are bad, not only because I knew what the reaction to this would be but also because it wasn't.

"My time in Dynamo made a very good player of me. I had 12 years at the club. They helped me start a professional career. Our motivation was not politics."

As the Cold War thawed towards the end of the 1980s, both players were able to keep up more regular contact with their families, while also contributing on the pitch after their suspensions expired. That they would appear every Saturday night on the Bundesliga highlights programmes - still watched secretly in so many East Berlin homes - was a source of great pride for their parents.

Götz stayed at Leverkusen until 1988. After winning the Uefa Cup, he left to join Cologne.

Schlegel left Leverkusen in 1985 and had a season with Stuttgart before signing for Blau-Weiss Berlin in 1986. He now lived on the west side of the city where he was born. But of course, he could never cross to the other side.

He only managed to see his mum and dad again in 1987, in Czechoslovakia. For Götz it was the summer of 1988, in Hungary.

Then came 9 November 1989.

Schlegel was in a hotel with his team-mates when he heard the news. He'd just got back from training when someone shouted over from the bar: "Hey Dirk, the wall has come down."

He thought it was a joke - for at least five minutes he wouldn't believe it, even after he'd seen the TV pictures, the thousands of smiling East Germans walking through checkpoints, past the barbed wire, past the spotlights, past the stunned border officials. What now exactly?

"I said: 'Oh come on! The wall came down and I was not in Berlin!' We could hardly have been further away in Germany too - we were playing an away match against Schalke," says Schlegel.

"That was just a crazy experience for me; it was unthinkable. Watching it, I thought maybe it's a drama or a movie. It was something unbelievable.

"On the weekend, I came back from the game at Schalke and my family finally came over to visit me with two friends. We had dinner at home, talking, drinking."

It wasn't until December that Götz returned to the East side of Berlin for the first time since he and Schlegel had left with their Dynamo team-mates in 1983. He went back home - "nothing had changed, it was exactly the same" - and spent time with his family during that season's winter break. His mother could finally pass on the few belongings she had been able to hide and keep safe for him.

Thirty years on, Schlegel, 58, and Götz, 57 are still close friends.

They enjoy looking back on their daring feat and speak regularly - usually by phone as Götz still lives on the other side of the country.

"My son is very proud," says Schlegel as we talk at a cafe near his west Berlin home.

Now he has to go. He and Götz are employed as scouts; work is calling.

I don't even have to ask the final question.

"I have been asked on many occasions," Schlegel says. "Would I do it again?

"Absolutely. Without question. Every time. I did it for my life. It was about setting up my future, shaping my life, choosing my own path."

Comments

Join the conversation

It struck me very hard that people were still being shot and killed in 1989 - I'd thought all that was in the past. Sadly not. Crosses by the Reichstag bore their names.

It's really not that long ago. Peace and freedom in Europe need protecting.

A great football story, a great human story and one, which I am so pleased had a happy ending.

KGB v Stasi.

It must be a rare occasion where the authorities knew nothing about the opposition players & everything about their own.

this is why we need to leave de EU #no-deal brexit

—

Really? You read this story and the only thing you have to say is some meat-headed nothingness about brexit?

I actually feel sorry for people like you.

This is why I pay my license fee.