“[Emily] had to think – she was the only one of us who had that to do. Father believed; and mother loved; and Austin had Amherst; and I had the family to take care of.”

– Lavinia Dickinson (Emily Dickinson’s Home, pp. 413-414)

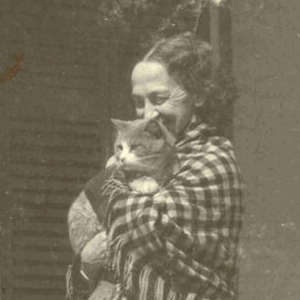

Lavinia Dickinson, ca. 1896

One of the most significant people in Emily Dickinson’s life was her sister Lavinia. Born two years after Emily, on February 28, 1833, the two were raised as if of an age. They began attending Amherst Academy together in the spring of 1841 at ages ten and eight, and shared a room and a bed into their twenties. Each, however, had her own circle of friends and very different personality. As Emily once told a friend, “if we had come up for the first time from two wells where we had hitherto been bred her astonishment would not be greater at some things I say” (Sewall, Lyman Letters, 70).

Vinnie grew to be the practical sister, who did the errands and managed the housekeeping. “I don’t see much of Vinnie – she’s mostly dusting stairs!” (L176) Emily once sighed. Clever and pretty, musical and an accomplished mimic, Vinnie had a sharp tongue and sometimes shaded the truth, nor was she a serious student. After eight years at Amherst Academy and two terms imbibing an “abbreviated course” at Ipswich Academy, she settled into an active social life in Amherst for several years. Her friendly flirtatiousness attracted the Amherst College students, but despite several proposals of marriage, including a long-term “understanding” with the Dickinsons’ friend Joseph Lyman, Vinnie, like her sister, remained unwed.

“Upon her, very early, depended the real solidarity of the family,” her niece Martha later wrote. “It was Lavinia who knew where everything was, from a lost quotation to a last year’s muffler. It was she who remembered to have the fruit picked for canning, or the seeds kept for next year’s planting, or the perfunctory letters written to the aunts” (Bianchi, Life and Letters, p. 13). Vinnie shared her mother and sister’s horticultural talents. Her passion for colorful, overflowing flower beds was exceeded only by an equally abundant love of cats, which followed her in procession about the Homestead.

Different as they were, the sisters were extremely close. While Austin was often exasperated by his youngest sister, the poet called her bond with Lavinia “early, earnest, indissoluble” (L827). Indeed, from young womanhood, Emily depended upon Vinnie’s physical presence when engaged in social activities or even going through the seasonal construction of new clothing, for Vinnie worked with the dressmaker and served as model for both of them. As she neared age thirty, the reclusive poet admitted, “Vinnie has been all, so long, I feel the oddest fright at parting with her for an hour, lest a storm arise, and I go unsheltered” (L200).

Vinnie’s pride in her brilliant sister was as strong as her devotion to protecting her. After their father’s death in 1874 and their mother’s stroke the following year, Vinnie and Emily, with the help of their maid Margaret Maher, cared for their invalid mother until her death in 1882. When Emily died in May 1886, Vinnie burned her sister’s correspondence, as requested, but to her amazement discovered hundreds of poems about which Emily had given no instructions. Determined to share these with the world, Vinnie spent the next thirteen years successfully urging and cajoling others – Susan Dickinson, Mabel Loomis Todd, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, the publishers Roberts Brothers – to publish her sister’s poems and letters. Without what Emily called Vinnie’s “inciting voice” (L827), we would know little or nothing of Dickinson’s great lyric poetry.

Lavinia Dickinson died at age 66 of an “enlarged heart” on August 31, 1899. Her health and spirits suffered greatly the last two years from the strain of the lawsuit with Mabel Loomis and David Todd, the death of her nephew Ned, and recriminations that flew between the Homestead and The Evergreens.

Further Reading:

Bianchi, Martha Dickinson. The Life and Letters of Emily Dickinson. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1924.

Bingham, Millicent Todd. Emily Dickinson’s Home. New York, Harper & Brothers, 1955.

Sewall, Richard B. The Life of Emily Dickinson. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1974. 138-157.

Sewall, Richard B. The Lyman Letters: New Light on Emily Dickinson and Her Family. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1965.