During the first few days of the trial of Keith Raniere, the man accused of leading a sex cult in the guise of a Randian self-help group, the prosecution presented a remarkable chart. It showed Raniere’s inner circle with photographs of the 25 men and women who co-founded, worked for, or otherwise cooperated in NXIVM, Raniere’s company, and ESP (Executive Success Programs), the “personal development” courses that have ensnared at least 16,000 people over the last 20 years. The faces around Raniere included actress Allison Mack, Seagram heiress Clare Bronfman, co-founder Nancy Salzman and her daughter Lauren, all of whom have pleaded guilty to different charges as part of the process against Raniere.

Coverage of the evidence has mostly focused on Mack or Bronfman, prominent figures who tarnished their reputations to protect a dreadful man. For me, though, the diagram offered a different, more chilling piece of information: Almost half of Raniere’s closest associates were Mexican. The list included Emiliano Salinas, son of former President Carlos Salinas, and Rosa Laura Junco, whose family owns one of Mexico’s most influential newspaper groups. The prosecution then provided another chart. The pictures of eight women around Raniere, all members of Dominus Obsequious Sororium (DOS), an alleged sex ring masquerading as a sorority in which women were enslaved and branded with Raniere’s initials. Five of the eight women were Mexican.

One would think that given the number and nature of Raniere’s Mexican associates, the story would have caught fire in Mexico. In fact, the opposite happened. Raniere’s deep Mexican connections have been conspicuously underreported by the country’s press. Different media outlets offered Salinas, an eloquent speaker whose father served as president from 1988 to 1994, softball interviews and numerous other opportunities to distance himself from Raniere, a man he had defended vehemently in the past, calling him “heroic.” Salinas and his business partner, Alejandro Betancourt, eventually announced they would sever ties with ESP, the self-help program they had helped create, promoted, and managed in Mexico for over 15 years. Salinas then claimed he was unaware of the existence of the alleged sex ring. With two noteworthy exceptions, almost no one in the Mexican press has dared to really probe his claim. The investigative website Aristegui Noticias published five recordings in which Salinas fully acknowledged and justified the existence of the secret branding group, while the news site Univision Noticias (for which I work) ran a series of pieces on Raniere written by journalist Gerardo Reyes. Other than that, the silence from Mexico has been deafening.

It’s unfortunate.

Raniere’s involvement in Mexico was unlike anything he attempted throughout his career as self-anointed cult leader. In Mexico, Raniere found a cult leader’s trifecta: access to the country’s political elite, gullible followers with deep pockets, and a country in crisis that could offer him both influence and money. The documentary film Encender el Corazón (“Turn on the Heart”), one of Raniere’s last projects in Mexico, offers some clues to his intentions. Directed by South African filmmaker Mark Vicente, one of Raniere’s associates, it is set in Mexico during the country’s brutal drug war. When I interviewed him in 2017, Vicente told me the movie was originally meant to suggest a way out for the country’s spiral of violence. Instead, the film became a recruiting video for NXIVM.

Encender el Corazón focuses on Raniere—bespectacled, slightly disheveled, and mild-mannered—surrounded by adoring Mexican followers, many of them Mexicans who would later appear in the prosecution’s trial charts. Raniere indeed offers a solution of sorts for Mexico’s troubles: Follow his teachings to the letter. In his messianic scheme, the country would become an experiment.

The film shows Raniere advising Julian Lebaron, a serious and hardworking man whose brother, Benjamin, had been brutally abducted from his home and killed just outside their Mormon community in northern Mexico in 2009, afer having refused to pay ransom for the kidnapping of another of the Lebaron brothers. Raniere latched onto Lebaron’s story to suggest a path of supposed nonviolent resistance in Mexico. Mexicans (the poor in particular), Raniere said, should lead a “peaceful revolution,” simply declining to take part in unlawful activities, accept extortion, or, like in Lebaron’s case, capitulate to criminal demands. The film’s oversimplified and risky diagnosis of Mexico’s inequality and the country’s convoluted 12-year war on crime could have been harmless if it weren’t a thinly veiled disguise for something different: a massive propaganda effort to raise Raniere’s profile in Mexico. The film ends with a call to action unrelated to Lebaron’s harrowing story or violence in Mexico: Join Raniere’s movement.

When I later spoke to Lebaron, he was stunned. “I never agreed for the film to be used as a recruiting tool of any kind,” he told me. As for the possible consequences of his peculiar strategy to abate Mexico’s violence, Raniere seemed nonchalant. One of the film’s producers would later tell me Raniere was aware that his method could lead to further bloodshed: Nonviolent resistance might be met with an increasingly desperate and violent response from the country’s criminal organizations. It would be, he probably reckoned, a small price to pay to be proved right.

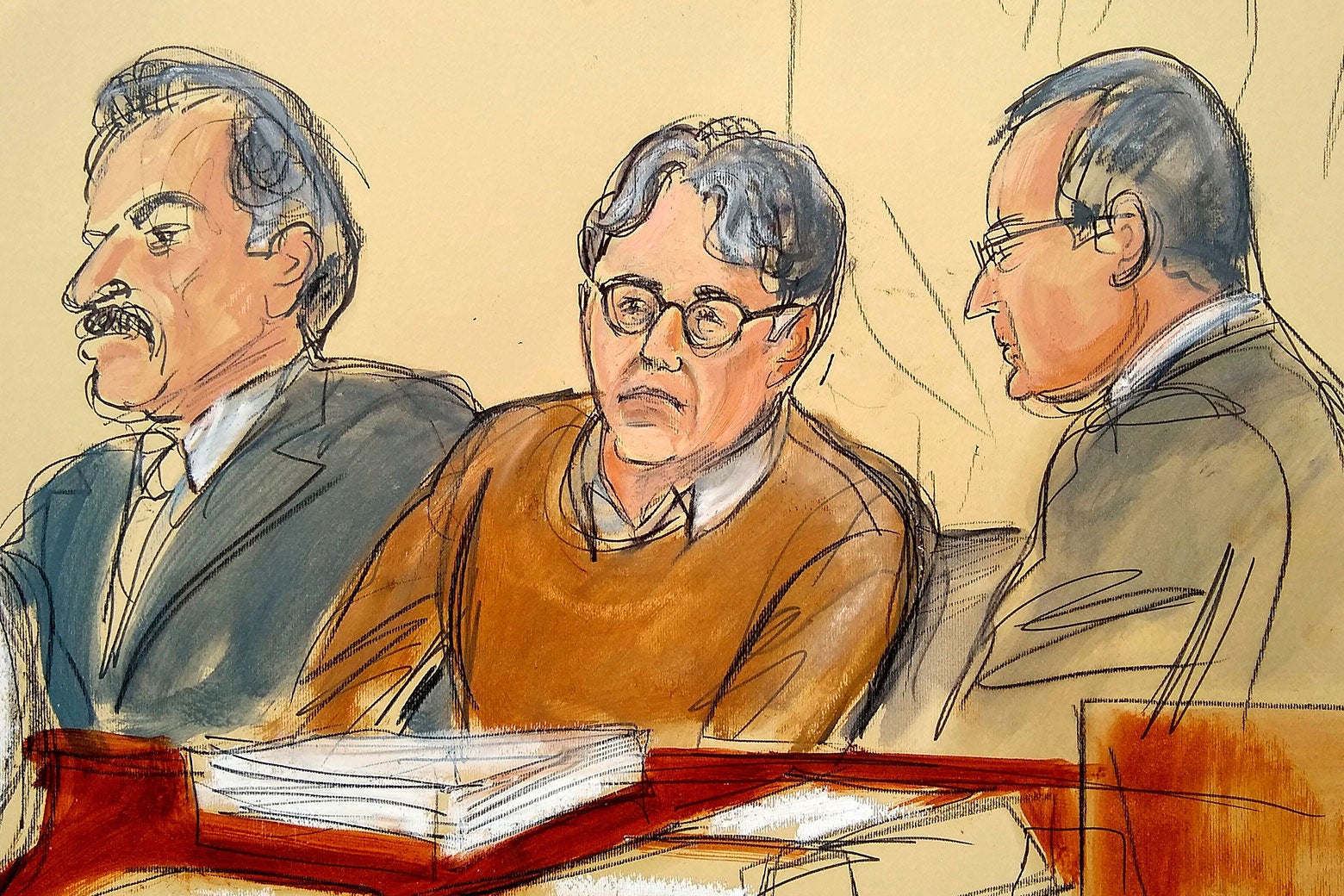

Raniere never got to put his nation-building model for Mexico to the test. In October 2017, the New York Times broke the shocking story that would eventually lead to his capture and trial. One of Raniere’s close associates, a woman named Sarah Edmonson, had fled the group after being branded with a cauterizing device as part of DOS. A few months later, in March 2018, Mexican authorities arrested Raniere in Puerto Vallarta, along the country’s Pacific coast. He would be charged with sex trafficking soon after. Mark Vicente, the film director, was one of the prosecution’s first witnesses. “It’s a fraud, it’s a lie,” Vicente said in court. “This well-intentioned veneer covers a horrible evil.”

If recent revelations are any indication, the prosecution will likely uncover the full extent of NXIVM’s network in Mexico. While he currently doesn’t face charges in the United States, prosecutors recently identified Salinas as one of Raniere’s alleged “co-conspirators.” In her trial testimony, Lauren Salzman named Rosa Laura Junco as the woman who recruited her into DOS. (Junco was also apparently responsible for buying a house for members of the sex ring group near Albany, New York.)

Some of Raniere’s Mexican associates and victims are expected to take the stand in Brooklyn, New York, in the next few days. If that’s the case, major Mexican media outlets, some of which have slowly begun to air pieces mainly about the trial, may have no choice but to treat the story as what it truly is: a shocking and unprecedented affair that transcends the Brooklyn legal proceedings and reached the upper echelons of Mexican society and the country’s political establishment. To do otherwise would not only be journalistic malpractice, it would also offer undeniable proof that, in Mexico, political connections can still be more relevant than the full pursuit of the truth.