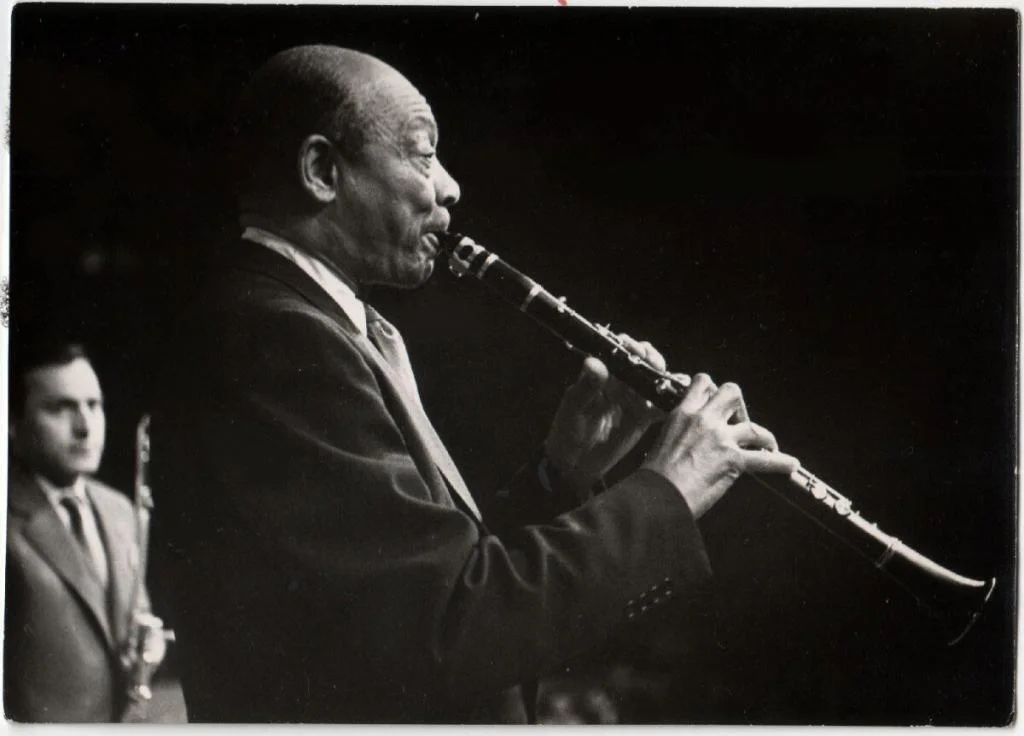

Edmond Hall was one of a handful of jazz musicians who could be identified after one note. Playing on a famous filmed version of “St. Louis Blues” from 1957 with Louis Armstrong’s All-Stars, Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic, a note by Hall changed the entire piece. After Armstrong had played some beautiful ballad phrases with the backing of strings, Hall launched the swinging second half of the performance with a long bent and piercing note, pushing the rendition towards joyful hysteria. Look up that note sometime! (Louis at 2:40, Hall at 3:15)

Hall was such a distinctive soloist that it is strange to think that he did not have his own sound until he was already in his mid-thirties. It was a slow start to his career but he would create memorable solos for 30 great years.

Edmond Hall was born May 15, 1901 in Reserve, Louisiana, forty miles west of New Orleans. He was literally surrounded by music from the start. His father Edward Hall played clarinet with the Onward Brass Band, an ensemble that also included three of his uncles (all brothers of his mother): clarinetist Lawrence, trombonist Jules and guitarist Edmond Duhe. Two of his own brothers, Herb Hall (who later had a strong career) and Robert Hall, became clarinetists. Edmond began on the guitar (taught by Edmond Duhe) but, according to brother Herb), he learned how to play the clarinet within five days.

Hall worked as a manual laborer until 1919 when the 18-year old moved to New Orleans. It did not take him long to find jobs with local groups, working with the legendary but unrecorded cornetist Buddy Petit during 1921-23. Hall spent a period in Pensacola, Florida, playing with Lee Collins, Mack Thomas, the Pensacola Jazzers, and, most significantly, Alonzo Ross’ DeLuxe Syncopators. He made his recording debut with the latter group in 1927, playing clarinet, soprano, alto, and baritone on eight songs. A fine section player and a versatile musician, Hall was still a decade away from creating his own musical personality.

In 1928 he moved to New York City, spending most of 1929-35 as a member of the Claude Hopkins Orchestra. Hall was one of three reed players, alternating between clarinet, alto and baritone. While he recorded regularly with Hopkins, who led a top-notch early swing band, and was obviously valued for his musicianship, no memorable solos of his were documented.

The real Edmond Hall first emerged on record in 1937 when he was two months shy of turning 36. Most top musicians have their own sound long before that age. Hall became a full-time clarinetist working with Billy Hicks’ Sizzling Six, giving up the saxophones. His recordings with Hicks, Frankie Newton’s Uptown Serenaders, and Henry “Red” Allen heralded his arrival. He also recorded with Billie Holiday next to Lester Young (including “Me, Myself And I” and “A Sailboat In The Moonlight”), Mildred Bailey, and Midge Williams during that period.

Edmond Hall’s big band days were over. No longer would he be reading arrangements while sitting buried in saxophone sections. He worked in hot jazz combos led by Zutty Singleton, Joe Sullivan, and the rambunctious Red Allen (1940-41), and recorded with those three groups in addition to Art Tatum, Ida Cox, Lionel Hampton, Josh White, and even W.C. Handy. He became a regular at Café Society and during 1941-44 was a member of the Teddy Wilson Sextet.

Edmond Hall’s first session as a leader was quite unique. On a set for Blue Note, he led his “Celeste Quartet,” a group matching his clarinet with Meade Lux Lewis on celeste, Charlie Christian (the electric guitar pioneer’s only recordings on acoustic guitar), and bassist Israel Crosby. What better band to record a song called “Celestial Express?” “Profoundly Blue” from the date became a minor hit. Hall also led a heated all-star Dixieland session for Blue Note in 1943 that featured trumpeter Sidney DeParis, trombonist Vic Dickenson and pianist James P. Johnson.

He came in second place to Benny Goodman in Esquire’s All-American jazz poll of 1943, resulting in him getting to record with Coleman Hawkins and the Esquire All-Stars. Hall became a regular for the Commodore label where he played on many hot swing sessions. And in late 1943, he entered the world of Eddie Condon. The result of the latter was a decade that was a whirlwind of constant activity.

Hall originally would play and record with Eddie Condon as a substitute for Pee Wee Russell, but in time he earned his own position, appearing on some of Condon’s famed Town Hall Concerts. The consistently exciting radio broadcasts have been fully reissued by Jazzology. Hall led his own group at Café Society and put together a similar band to back Louis Armstrong during a 1947 Carnegie Hall concert. Armstrong had been debating about breaking up his big band to form a sextet, and the success of this concert helped him to make that decision.

The clarinetist had a group for a time with Wild Bill Davison, was a regular on Rudi Blesh’s This Is Jazz broadcasts, and spent part of 1948-49 in Boston including working with Bob Wilber’s combo. He worked at a few jobs with Bunk Johnson and made quite a few recordings as a leader for Blue Note. Among his many recorded sideman appearances were dates with Art Hodes, Sidney DeParis, James P. Johnson, Eddie Condon, Bud Freeman, Mary Lou Williams, Mutt Carey, Punch Miller, and even Gene Krupa. Everyone wanted to play with Edmond Hall.

During 1950-55, Hall performed nightly at Condon’s in New York, sometimes as the only African-American musician on the bandstand. He consistently broke color barriers throughout his career because of his talent and unique sound. No one else sounded like him. During this period, Hall also took time off for other jobs including with Ralph Sutton, Mel Powell and Jack Teagarden.

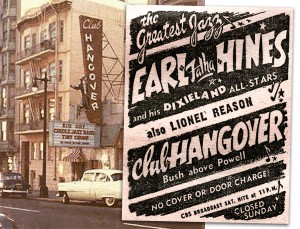

Louis Armstrong remembered Edmund Hall’s playing from the 1947 concert and was delighted when his manager Joe Glaser got Hall as the permanent replacement for the departed Barney Bigard in 1955. Ironically 13 years before, Hall had turned down an offer to be Bigard’s successor in Duke Ellington’s orchestra because he wanted to stick to freewheeling settings. Three days after finishing an album with Condon, Hall was already recording as a member of the Louis Armstrong All-Stars.

The playing of Hall next to Armstrong and trombonist Trummy Young gave the All-Stars a very extroverted, boisterous, and inspired frontline. His period with Armstrong was quite eventful. He was in the film High Society, even having his name mentioned by Bing Crosby during “Now You Has Jazz.” Hall is on the hit version of “Mack The Knife,” the Satch Plays Fats album, and the box set Satchmo – A Musical Autobiography. He appeared regularly on television with the All-Stars including the Timex All Star Jazz Shows.

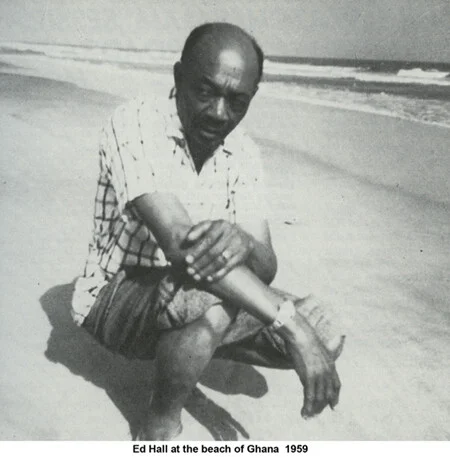

These were the Ambassador Satch State Department-sponsored globetrotting years. In addition to regular performances in the United States, Hall got to perform throughout Europe (including Scandinavia, Italy, Spain, France, and England), Australia, South America, and before huge crowds in Africa including in Ghana; some of this appeared in Edward R. Murrow’s Satchmo The Great documentary. Edmond Hall had the highest visibility of his life.

But the constant traveling got to him and Hall left the All-Stars in 1958. He took a nonplaying vacation in California. Rejuvenated, he returned to New York and his busy freelance career, working with Eddie Condon, Red Allen, Ralph Sutton, J.C. Higginbotham, and Teddy Wilson among others. Hall led a couple albums of his own during 1958-59, welcoming his brother Herb Hall to a few selections.

But the constant traveling got to him and Hall left the All-Stars in 1958. He took a nonplaying vacation in California. Rejuvenated, he returned to New York and his busy freelance career, working with Eddie Condon, Red Allen, Ralph Sutton, J.C. Higginbotham, and Teddy Wilson among others. Hall led a couple albums of his own during 1958-59, welcoming his brother Herb Hall to a few selections.

In 1960 Edmond Hall and his wife Winnie returned to Ghana where he hoped to start a music school. However that venture did not last long and he was soon back in New York. Still just 60, he remained active. Among his activities from the 1961-65 period were recording with Chris Barber both in the U.S. and on a tour of England, working briefly in 1962 and on a 1964 Japanese tour with the Dukes of Dixieland, and performing with the Newport Jazz Festival All Stars. He was also always welcome to play with the Eddie Condon Gang and stayed as busy as he wanted.

In November 1966 Edmond Hall went to Europe for the last time, working with Alan Elsdon’s band and performing in England, Germany, Denmark and Sweden. While in Copenhagen he had the chance to play and record with Papa Bue’s Viking Jazz Band.

Producer John Hammond had been an Edmond Hall fan back in the 1930s, helping to get him jobs and recording dates starting in 1937. On January 15, 1967 he invited Hall to participate in his 30th Anniversary Spirituals To Swing concert at Carnegie Hall. The clarinetist played in a group with trumpeter Buck Clayton, tenor-saxophonist Buddy Tate, and either Count Basie or Ray Bryant on piano, performing “Swinging The Blues” and on numbers with singers Big Joe Turner and Big Mama Thornton. While boogie-woogie great Pete Johnson, who had suffered a major stroke, was only able to play one-handed on “Roll ‘Em Pete” and was obviously not long for the world, no one had the idea that the end was so near for Edmond Hall.

He played a few more concerts, still sounding great on a live set with cornetist Bobby Hackett from February 3, 1967, that was later released on a Jazzology CD. But on February 11, Edmond Hall died of a heart attack while shoveling snow in front of his home in Boston. He was 65.

When one thinks of the greatest clarinetists in jazz history, the name of Edmond Hall usually does not come immediately to mind. But more than a half-century after his death, no clarinetist has emerged on the scene that sounds like Hall or can exceed the excitement he caused every time he picked up his instrument.