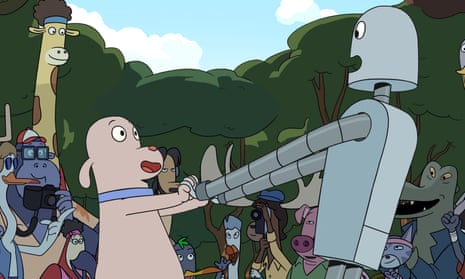

It’s an almost entirely dialogue-free animation, captured with pleasingly simple, almost naive 2D character design. The warm and disarming storytelling is bolstered by the film’s unassuming use of humour. But come to Robot Dreams well stocked with tissues: Pablo Berger’s exquisite, bittersweet, Oscar-nominated buddy movie about the bond between a dog and a robot matches Spike Jonze’s Her as one of cinema’s most devastating and profound studies of loneliness and the fragility of emotional connections. If any further evidence were needed to support the theory that we are enjoying a new boom time for quality animation, then this is it.

The appealingly clean, uncomplicated character design is based on that of the source material, a graphic novel by American author and illustrator Sara Varon. She has made something of a career from exploring odd-couple relationships: one of her other books, Bake Sale, is about the friendship between a cupcake and an aubergine. Another, Chicken and Cat, is playfully referenced in Robot Dreams, namechecked on the buzzer for the apartment below that of Dog.

Home for Dog is a modest third-floor apartment in New York’s East Village in the 1980s. It’s a solitary existence: the shelves are full of jigsaw puzzles and the freezer is well stocked with microwave macaroni cheese meals for one. But life in 80s New York City is not designed to be experienced solo. Bathed in the borrowed light from his TV screen, Dog slumps on his sofa and plays Pong against himself. Picking listlessly at his cheesy pasta gloop, he scrolls through the television channels for something to distract himself from the happy couple snuggling in the window across the street. And then he sees it: an advertisement for a robot companion, the Amica 2000. Pretty soon, accompanied by a jaunty, optimistic piano and xylophone ditty, Dog assembles his new flat-packed friend.

The bond is instant. Bucket-headed and wide-eyed, Robot approaches the city with a sense of wonder. And through his friend’s hunger for discovery, Dog starts to rediscover New York as a place to be embraced and experienced, rather than watched, wistfully, from his living room window. In a blissful montage set to Earth, Wind & Fire’s September (a recurring musical motif, used to increasingly wrenching effect), the buddies scoff down hotdogs from street vendors, watch an octopus busker bashing drums on the subway, rollerskate together in Central Park. At the end of a fun-packed summer the pair venture to the beach at Coney Island, where Robot flings himself, literally, into the seaside experience.

Then disaster strikes. The saltwater short circuits his power bank and Robot is left, immobile, on the beach. Unable to lift his metal bestie, Dog returns the next day with his toolkit, only to discover that the beach has closed for the season and won’t reopen until the following June. Rusting at the edges and exposed to the elements, Robot lies patiently in the sand. When he sleeps, he dreams of reuniting with Dog. The ache of enforced separation is dulled by brief connections – Robot with a family of birds that nest in his armpit; Dog with a cool female Duck, who rides a motor scooter, wears Air Jordans and knows how to fly a kite. But both Robot and Dog are counting the days until they can be reunited again.

There’s such tenderness to the storytelling, such empathy and emotional depth, that it broadens the film’s potential audience from kids, who will respond to the cute characters and gentle wit, to adolescents and adults, who will recognise the angst and awkwardness of trying to function alone once again. What is perhaps remarkable is that this is Berger’s first animated film. The multi-award-winning Spanish director was previously best known for Blancanieves, a reimagining of the Snow White story set in 1920s Seville, and Torremolinos 73, a droll comedy about a struggling encyclopedia salesman who stumbles into the world of adult cinema.

What Berger has created with Robot Dreams is not just one of the finest animations of recent years; it’s also one of the most persuasive love letters to the city of New York. The time and location are etched in affectionate details into every frame, from the period-specific graffiti to the cultural references (Dog is visited by a trick-or-treating sloth dressed as Freddy Krueger), to the East Village in-jokes (a rented VHS of The Wizard of Oz comes from Kim’s Video, a now fabled video store that was run from the back of an East Village dry cleaners). It’s a city that is vibrantly present in the film’s evocative sound and meticulously captured in the background design. But, as Dog and Robot discover, it fully comes to life when it’s shared.