Velázquez, Diego Rodríguez de Silva y

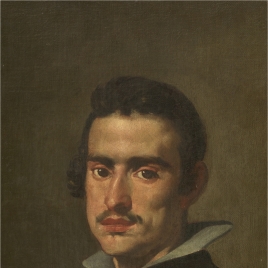

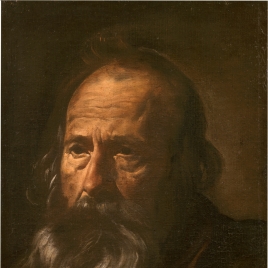

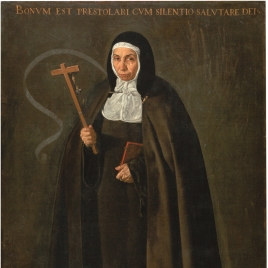

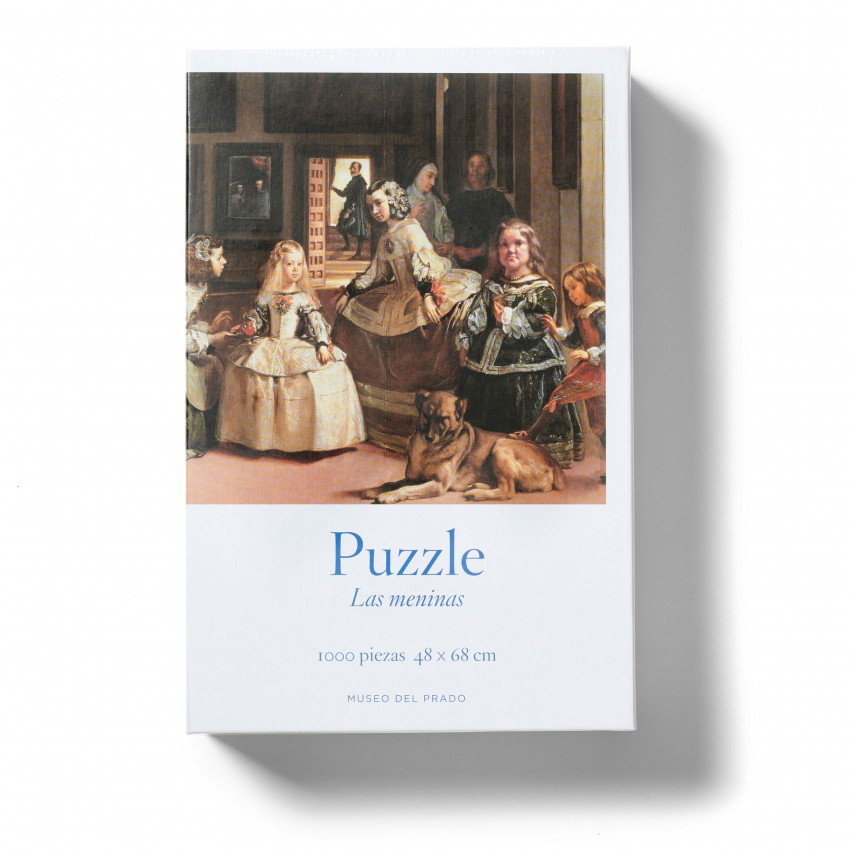

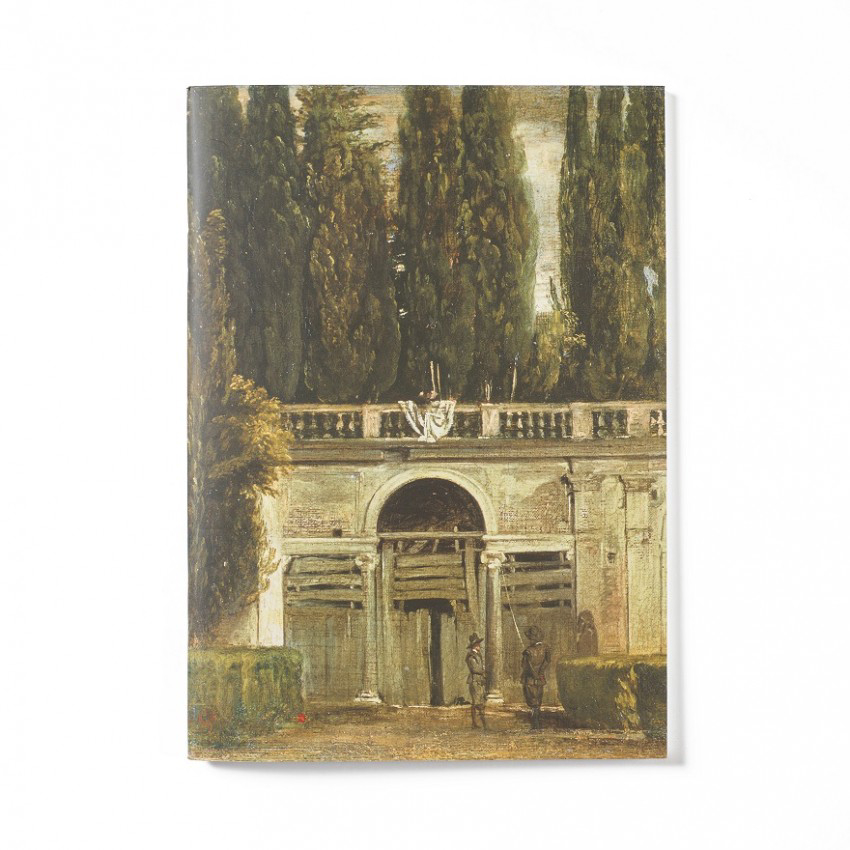

Sevilla (Spain), 1599 - Madrid (Spain), 1660Born in Seville, Velázquez adopted his mothers surname, as was common in Andalusia, signing “Diego Velázquez” or “Diego de Silva Velázquez". He studied painting and worked professionally in his native city until he was twenty-four, then moved with his family to Madrid. There, he entered the king’s service, remaining until his death in 1660. Much of his work was painted for the royal collection and later entered the Museo del Prado, where it remains today. Most of the paintings he made in Seville, however, entered foreign collections, especially from the 19th century onward. Despite a growing number of documents relating to his life and work, much of what we know comes from his earliest biographers. In a treatise completed in 1638 and published in 1649, Velázquez’s teacher, Francisco Pacheco, who later became his father-in-law, furnished important though fragmentary information about his apprenticeship, his first years at court and his first trip to Italy, with abundant personal details. The artist’s first complete biography, by Antonio Palomino, was published in 1724, over seventy years after his death, but its value lies in the fact that it is based on biographical notes written by one of Velázquez’s last disciples: painter Juan de Alfaro. As a court painter himself, Palomino was intimately familiar with Velázquez’s works in the royal collection, and he also had contact with people who had known the painter when they were young. Palomino adds much to the fragmentary data offered by Pacheco, including important information about Velázquez’s second trip to Italy, his activity as a chamber painter, as a palace official and as the person in charge of the king’s artworks. He also includes a list of the favors Velázquez received from Philip IV, along with his responsibilities at the Royal Household and the text of the epitaph written in Latin by Juan de Alfaro and his brother, a physician, and dedicated to the “eminent painter from Seville” (“Hispalensis. Pictor eximius”). In Velázquez’s time, his native city was an enormously wealthy center of commerce with the New World, an extremely important ecclesiastical seat and home to that century’s great religious painters, whose works it conserved. According to Palomino, Velázquez was a disciple of Francisco de Herrera before he entered Francisco Pacheco’s studio at the age of eleven. At that time, Pacheco was the most prestigious teacher in Seville; a man of culture, a writer and a poet. After six years in the “gilded cage of art,” as Palomino called it, Velázquez was certified “master painter of imagery and in oils […] with license to practice his art throughout the realm, to sell to the public and to take apprentices.” We do not know whether he took advantage of that license to employ apprentices in Seville, but it is not unlikely, given the repetitions of the still lifes he painted there. In 1618, he married Pacheco’s daughter, “taken with her virtue […] and the promise of her natural and considerable intelligence.” Velázquez’s two daughters were subsequently born in Seville. Later, when his disciple and son-in-law was already established at court, Pacheco wrote that his success was the result of his studies, insisting on the importance of working from life and drawing. Apparently, Velazquez had a young villager who posed for him, and while none of his drawings of this model has survived, his early works are striking in their repeated depiction of the same faces and persons. Pacheco makes no mention of religious paintings from Seville, although he would have had to approve them, both as a specialist in religious iconography and as a censor for the Inquisition. What he does mention as praiseworthy are Velázquez’s still lifes. These kitchen and tavern scenes with figures include objects arranged as still lifes that constitute a new type of composition whose popularity in Spain is largely due to Velázquez. In such works, as well as in his portraits, Pacheco’s disciple attained “the true imitation of nature,” following in the footsteps of Caravaggio and Ribera. In fact, Velázquez was one of Spain’s first exponents of the new naturalism drawn directly or indirectly from Caravaggio. Indeed, The Waterseller of Seville (ca. 1619, Ellington Museum, London) was attributed to Caravaggio when it arrived in London in 1813. This was one of the first works to make Velázquez’s great talent known in Madrid, but when he moved to that city for the first time in 1622, it was with the then futile hope of painting the monarchs. That year, Pacheco asked him to make a portrait of poet Don Luis de Góngora y Argote (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), and the resulting work was much admired and later copied in drawings and engravings. This undoubtedly helped to strengthen his reputation as a portrait painter in the capital. When he returned to Madrid the following year at the behest of the Count-Duke of Olivares, he painted Philip IV’s likeness. The young monarch, who had only been king for two years, rapidly appointed him chamber painter, and this was the first of his many palace occupations, some of which included burdensome administrative responsibilities. From then on, he did not return to Seville. In fact, he rarely left Madrid except to accompany the king and his court. He only left the country twice, visiting Italy on a study trip, and later returning there with a commission from the king. The new atmosphere at court, which was famous for its ceremonial extravagance and rigid protocol, allowed him to contemplate and study the masterworks in the royal collections—especially the Titians. Like that great master from Venice, Velázquez painted portraits of the royal family, courtiers and distinguished visitors, and he undoubtedly drew on his workshop for the replicas of his royal likenesses. According to Pacheco, his first equestrian portrait of the king was exhibited on the calle Mayor “to the admiration of the court and envy of those in the arts.” It was hung in a place of honor, across from Titian’s famous equestrian portrait of Emperor Charles V on horseback at Mühlberg (Prado), in the hall decorated for cardinal Francesco Barberini’s visit in 1626. Velázquez’s portrait of the cardinal, however, was not appreciated due to its “melancholy and severe” depiction, and the following year, he was accused of only knowing how to paint heads. This affront led Velázquez to compete with three of the king’s painters, and he won with his Expulsion of the Moors (now lost). While his portrait of Barberini did not please its sitter, according to Pacheco, his works and his “modesty” were rapidly praised by the great Flemish painter, Peter Paul Rubens during his second trip to Spain in 1628. The two painters had already written to each other, and had collaborated on a portrait of Olivares that Paulus Pontius engraved in Antwerp in 1626. In that work, the Count-Duke’s head was drawn by Velázquez, while the allegorical setting was designed by Rubens. During the Flemish painter’s stay in Madrid, Velázquez was probably able to watch him painting royal portraits and copying works by Titian, and that must have increased his admiration for the two painters who most influenced his own work. Rubens’ example undoubtedly inspired the Spanish painter’s first mythological work, The Triumph of Bacchus, also known as The Drunkards (1628-1628, Museo del Prado), a subject that, in Velázquez’s hands, seemed closer to his still lifes than to the world of classical Antiquity. Apparently, a visit to El Escorial in Rubens’s company renewed the Spanish painter’s desire to visit Italy, and he began the journey in 1629. According to Italy’s representatives in Spain, the young portrait painter and favorite of both the king and Olivares intended to complete his studies there. Pacheco affirms that he copied Tintoretto in Venice and Michelangelo and Raphael at the Vatican. He then asked permission to spend the summer at the Villa Medici, where there were ancient statues to be copied. None of those copies has survived, and the self-portrait he painted at Pacheco’s request is also lost. Pacheco praised that latter work, affirming that it was executed “after the manner of the great Titian and (if I may say so) not inferior to his heads.” Proof of Velázquez’s advances in that period are two large canvases he brought back from Rome. Vulcan’s Forge (1630, Prado) and “Joseph’s Tunic” (1630, El Escorial) amply justify his friend Jusepe Martínez’s observation that “he arrived with a much better sense of perspective and architecture.” Moreover, in Velázquez’s hands, both the biblical and the mythological scene brought the independence with which he interpreted ancient statues to the nude torsos he depicted from live models. Returning to Madrid in 1631, Velázquez again concentrated on portraiture, entering a period of considerable and varied production. He also supervised and participated in the two main projects taking place in the realm at that time: the decoration of the new Buen Retiro Palace on the outskirts of Madrid, and the king’s hunting pavilion, known as the Torre de la Parada. His five royal equestrian portraits soon sumptuously adorned the new palace’s main hall, the Hall of Realms (completed in 1635), alongside his contribution to the series on military triumphs: The Surrender of Breda (Museo del Prado). The large canvas of Saint Anthony Abbot and Saint Paul, the First Hermit (ca. 1633, Museo del Prado) for the altar at one of the hermitages in the Retiro Palace gardens, reveals his talent for landscape. Indeed, it is so notable that it stands out among many other such works brought from Italy to decorate the palace. For the Torre de la Parada, Velázquez painted portraits of the king, his brother and his son, all dressed as hunters and with landscapes in the background, much like the equestrian portraits for the Buen Retiro and the Royal Cloth or Hunting Wild Boars in Hoyo de Manzanares (ca. 1635-1637, National Gallery, London). He also painted the figures of Aesop, Menippus and Mars (all in the Museo del Prado) for the Torre de la Parada, which were appropriate subjects for that location and not unlike the mythological scenes that Rubens and his school in Antwerp had been commissioned to paint. Around that time, Velázquez also painted his portraits of buffoons and dwarves, including four seated figures outstanding for their characterizations and for the adaptation of diverse postures to their deformed bodies. That same sensitivity is clear in the festive air he brought to The Crowning of the Virgin (ca. 1641-1642, Museo del Prado), which he painted for the queen’s prayer chapel at the Alcázar. This work is a vivid interpretation of a Rubens composition in Velázquez’s own language. Similar in its rich colors, although more reminiscent of Van Dyck than of Rubens, Velázquez’s striking Philip IV at Fraga (1643, Frick Collection, New York) was painted to celebrate one of the army’s most recent victories. From then on, he did not paint another portrait of the king for over nine years. Despite many military, economic and family problems, Philip IV never lost his passion for art, nor his desire to continue expanding his collection. He therefore commissioned Velázquez to return to Italy in search of paintings and ancient sculptures for his collection. The painter left Madrid in January 1649, shortly after his appointment as the king’s chamber aide. His baggage included paintings for Pope Innocence X on his Jubilee. Velázquez’s second trip to Italy had important consequences for both his personal life and his career. In Rome he had an illegitimate son, Antonio, and he also freed his slave of many years, Juan de Pareja. As to his commission: we know how successful he was, thanks to Palomino and to the relevant documents, and also that he was honored with an appointment as academician to the Academy of San Lucas and member of the Congregation of the Virtuous. Moreover, he received the patronage of the Curia during his stay in Rome. After his portrait of Juan de Pareja (1650, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) was exhibited at the Pantheon in Rome, Palomino stated that “according to all painters of all nations [who saw that work], everything else looked like painting, while this one looked real.” Velázquez’s greatest triumph at that time was earning the Pope’s permission to paint his portrait, which few foreigners had ever received. The result (Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome) later garnered him the Pope support when he sought permission to enter one of the military orders. Painted in the summer of 1650, it “stunned all of Rome, was copied by everyone as a study, and was admired as a miracle,” as Palomino stated without an ounce of hyperbole. There are multiple copies of this work that has inspired innumerable painters from the time it was painted to the present day. The impression of forms and textures created with light and color using free brushstrokes recalls Velázquez’s debt to Titian and foreshadows the advanced and highly personal style of his final works. On the basis of its style, originality and subject, The Toilet of Venus (1650-1651, National Gallery, London) would also seem to have been painted during his stay in Italy. This is the only surviving female nude by his hand, and it is filled with reminiscences of both Titian and ancient statuary, but its concept of a goddess in human form is characteristic of Velázquez’s own personal language, which was unique in his time. Returning to Madrid in 1652, with a new job as Palace lodging master (aposentador de Palacio), Velázquez took charge of the decorations of the Alcázar’s halls, using some of the artworks he had acquired in Italy. According to surviving statements, these included some three hundred sculptures. In 1656, the king ordered him to take forty-one paintings to el Escorial, including works purchased at the London auction of the executed English King, Charles I. According to Palomino, he drafted a report on those works that revealed his erudition and vast knowledge of art. Later, for the Hall of Mirrors, where the king’s favorite Venetian paintings were hanging, he painted four mythological canvases and designed the project for its ceiling, including the distribution of subjects to be painted by Bolognese artists that Velázquez contracted in Italy. And despite these occupations, Velázquez continued to paint, finding new models in the young Queen Mariana and her children. Queen Mariana of Austria (ca. 1651-1652, Museo del Prado) and The Infanta Maria Teresa, who was the king’s daughter by his first wife (1652-1653, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), closely resemble each other in these portraits. Their faces and figures are linked by the extravagant new fashions: enormous panniers, exaggerated hairdos and make-up that Velázquez captures with free brushstrokes and without defining their details. And with that same free hand, he manages to bring out the tender vitality of the young infantes, despite their stiff clothing. The final two portraits of Philip IV, copied in oils and engraving, are quite different (1653-1657, Museo del Prado; ca. 1656, National Gallery, London). These straightforward busts of the king dressed in dark suits are informal and intimate, and they reflect the physical and moral decay of which he was well aware. Philip had not been painted in nine years, and as he himself put it in 1653: “I am not inclined to be exposed to Veláquez’s phlegm, nor to see how I am aging.” In the final years of his life, despite his well-known phlegm and many worries, Velázquez added two masterful canvases to his oeuvre, both of which were original, new and practically unclassifiable: The Spinners or Fable of Arachne (ca. 1657, Museo del Prado), and the most famous of all, Las Meninas (1656, Museo del Prado). Both works show how Velázquez’s then-modern naturalism, his detailed realism, had evolved over the course of his career into a fleeting vision of the figure or scene. Up close, his audacious brushstrokes seem incoherent, but at the proper distance, they are optimal and exact in a way that somehow foreshadows the art of Édouard Manet and other 19th-century painters so powerfully influenced by Velázquez’s work. His final public act was a trip to the French border with the court to decorate the Spanish pavilion on Pheasant Island with tapestries for the infanta María Teresa’s wedding to Louis XIV (June 7, 1660). Just a few days after returning to Madrid he fell ill, dying on August 6, 1660. His body was dressed in the uniform of the Order of Santiago, which he had been awarded the year before, and he was buried, as Palomino put it, “with the greatest pomp and enormous expense, but not at all too much for such a great man” (Harris, E. in "Enciclopedia Museo Nacional del Prado", 2006, VI, pp. 2148-2156).