This has already been a World Cup of records for France, who are chasing a third title in less than a quarter of a century on Sunday. The captain, Hugo Lloris, will celebrate his 145th cap against Argentina, three more than the previous record holder, Lilian Thuram. Olivier Giroud equalled, then surpassed, the 52 goals that Thierry Henry had scored for Les Bleus. Antoine Griezmann, one of this tournament’s standout performers, has now played a barely believable 72 consecutive games for France.

Then there is Didier Deschamps, who will be attempting to win the World Cup for a third time to go level with Pelé, the only other person to have achieved that feat; Deschamps, one of only three men, the others being Brazil’s Mário Zagallo and Germany’s Franz Beckenbauer, to become a world champion as a manager and as a player; Deschamps who, if France win on Sunday, will have a legitimate claim to be considered the most decorated man in the history of the game; Deschamps, who only joined a football club at the age of 11, and has certainly made up for lost time since then.

Quick GuideQatar: beyond the football

Show

It was a World Cup like no other. For the last 12 years the Guardian has been reporting on the issues surrounding Qatar 2022, from corruption and human rights abuses to the treatment of migrant workers and discriminatory laws. The best of our journalism is gathered on our dedicated Qatar: Beyond the Football home page for those who want to go deeper into the issues beyond the pitch.

Guardian reporting goes far beyond what happens on the pitch. Support our investigative journalism today.

He had barely ever left his native Basque country when he became a boarder at La Jonelière, the sports centre where Nantes housed its young players. He was 14 at the time, 250 miles away from home. He felt lonely, and fearful, as the boys he roomed with, most of whom were much older than him, did not hide their dislike of the wonderboy whom a number of high-profile clubs had fought over before the teenager’s family had opted for the Breton club.

For the first but certainly not the last time in his life, Deschamps had to fight off the bullies to impose himself; and if he succeeded, it was not just down to his strength of will, but also thanks to a man 30 years his senior, Jean-Claude Suaudeau (“Coco” to everyone), a key player of José Arribas’s great 1960s Nantes side, who had just taken over the club’s senior team.

The age gap does not seem to have mattered for either. The older man was struck by his protege’s insatiable appetite for learning, as well as by his intelligence and his natural air of authority, making him the captain of one of the top teams in France at the age of 19, at a time when many of Les Canaris were full internationals. The younger one, who would look out from a dormitory window to see when Coco was walking his dog, and then would rush to join him, relished being taught by one of French football’s most eloquent teachers, the quasi-mystic who had refined and perfected the jeu à la nantaise, which, to quote its inceptor Arribas, was “not a system, but a state of mind in which each player must put his trust in his teammates and try to merge his own self in a whole”.

On the field of play this was translated – especially when Suaudeau became head coach of the side – into a style of play that verged on the poetic. Suaudeau’s Nantes were ravishing to watch, a living organism that moved as one, as if through liquid air; and Deschamps, hard as it can be to fathom now, was part of this work of art.

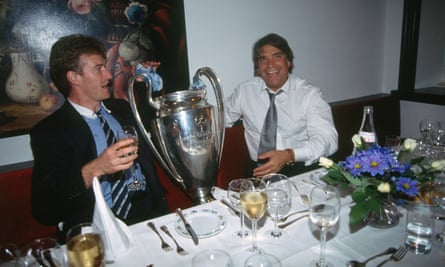

Yet Deschamps, product of the école nantaise that he is, Suaudeau’s spiritual son that he could have been, was to become one of football’s arch-pragmatists, at ease with the idea that he would often have to negate his impulses and qualities to succeed. The midfielder whom Eric Cantona derided as a “water-carrier” had started as a prolific striker and, according to Suaudeau, could have played in every position on the field. But he found that it was from midfield that he could assert his authority on the game; so a midfielder he turned himself into. Deschamps is the coach who, in his first managerial role, made Monaco one of Europe’s most attractive attacking sides and took them to a Champions League final in 2004, but was sacked a little over a year later, after his team, bereft of three of its best players, Ludovic Giuly, Fernando Morientes and Jérôme Rothen, failed to qualify for the same competition. Lesson learned. “A manager only exists through his results,” he said.

This would have been anathema to Suaudeau, and perhaps even to the young Deschamps; but the young Deschamps would not stay with his mentor long enough for Coco’s teachings to turn into articles of faith. He was sold, just as every one of the better nantais graduates was sold – Karembeu and Desailly and Makélélé– and ended up at Marseille. There his relationship with the owner, Bernard Tapie, was so fractious, contrary to what Cantona later suggested, that Deschamps – just like Cantona – was sent on loan to Bordeaux and had to fight like mad, again, to regain his place at Marseille when Tapie was bent on getting rid of him.

Deschamps won, and became a European champion in 1993. When he moved to Juventus a year later, a serious achilles injury forced him to sit out six months of his first season there and, again, he had to fight; and again, he won, to the extent that his manager, Marcello Lippi, trusted him more than anyone, including Antonio Conte, to be his messenger on the pitch. Whereas for Suaudeau, who defines himself as an educator, winning is “powerful but ephemeral”, for Deschamps, the born competitor, “pleasure can only exist in success”. The most revealing word here, of course, has to be “only”.

The two men met again in 2012 at the invitation of France Football magazine, just as Deschamps was about to succeed Laurent Blanc as the head of the France national team. Put in the presence of a man he still revered, Dédé lowered his guard as he rarely did then, and never does now. “I know that progress also means going through failure”, he told his mentor, “but, today, high-level football [‘le football de haut niveau’, an expression which pops up in all of his press conferences] is about winning. When I stopped playing, I asked myself the question: ‘Do I want to become a coach? And, above all, what kind of coach? Pass on what I know to the young ones?’ After all I’d been through, I couldn’t be satisfied with that. Impossible. I wouldn’t have been faithful to myself.” To which Suaudeau responded: “I never saw you as an educator. That’s because you’re not convincing enough. You’re a fantastic winner, but not a persuader.”

after newsletter promotion

Yet Suaudeau’s lesson has not been totally lost on Deschamps, judging by the way he has managed to take a team riddled with injuries, before and during the tournament, to a second consecutive World Cup final, with something that could, almost, pass for abandon when compared to France’s fun-free approach to previous tournaments.

He’s looked far more relaxed. He’s been seen smiling. France have played with more freedom and imagination than they have for quite a while in a proper competition.

Deschamps has not clipped Kylian Mbappé’s wings to compensate for Théo Hernandez’s obvious defensive frailties. Griezmann has dazzled in a protean role that appears to have been of his manager’s design. Responding to his player, who had said that “every match, every move is like a thank you I send [the manager]”, Deschamps commented: “I don’t have to love my players,” sounding like a gruff drill sergeant who has just been given a lovely Christmas present by his squaddies and can’t quite hide how chuffed he is by it all. “I’m not about to talk about love for my players … I don’t have to love them, I have to know them. With Antoine, as with other players who’ve been here for a long time, a relationship of trust has grown.”

And what was it that Arribas said the foundation of the jeu à la nantaise was? “Not a system, but a state of mind in which each player must put his trust in his teammates and try to merge his own self in a whole.” Perhaps the lesson was taught after all.