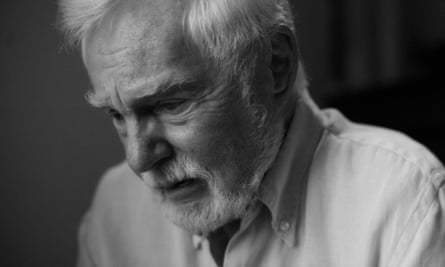

Derek Jacobi is having a bad hair day. “Oh, he butchered it,” wails the actor in mock despair. “It’s the worst haircut I’ve ever had.” Considering he is about to turn 84, there must be a fair few haircuts to choose from. The photographer and I reassure him that his snowy locks are rather dapper, and he seems instantly placated. “Do you think so? Oh, I take it all back then.” His voice is as soft and warm as butter melting on a crumpet, his manner sparkly and self-deprecating. When he is politely asked not to let his arm droop over the side of the chair while his picture is taken, he raises a hand in horror: “Was I being limp-wristed? We don’t want any of that!”

We are in the living room of the London home that Jacobi shares with his husband, the actor-director Richard Clifford, who has been his partner since the late 1970s. The paintings on the walls would make the house feel like a minor wing of the National Gallery were it not for the couple’s russet-coloured Irish terrier, Daisy, padding around the place. Jacobi, who is wearing a grey wool waistcoat, white shirt, blue jeans and navy running shoes, got back a few days earlier from his second home near Toulouse. “We watched the Queen’s funeral there,” he says. He still remembers his parents buying their first television specially for the coronation. He was 14. “We sat there with the curtains drawn, watching it in the dark.” It was only three years ago that he played the dying Duke of Windsor in The Crown. Art colliding with life, the past flooding in: no wonder the funeral hit him hard. “I cried the whole time. It was all done so well. Not a foot wrong, nothing out of place. Immaculate.” He could almost be reviewing a first night.

Through the windows behind him lies the garden, and beyond that the home studio where he does his voiceover work, such as the audiobook of Captain Sir Tom Moore’s autobiography, which he recorded during lockdown. Another job that came his way during that period was the British film A Bird Flew In, which follows the scattered lives of assorted creative types whose work is halted by the pandemic. Jacobi plays a veteran performer resting at home in France – which is precisely what he was doing at the time. He turned the role down at first. “I said, ‘No, no, I’m on holiday.’ My agent said, ‘They’ll come to you.’”

Jacobi hasn’t yet seen A Bird Flew In, so we move on instead to the film version of Alan Bennett’s play Allelujah, in which he stars as a patient in a geriatric hospital that is facing closure. Jennifer Saunders is the head nurse and Russell Tovey a go-getting management consultant, but it is Jacobi, as a former teacher, who supplies the pathos. “Ah, yes. Allelujah. That’s the hospital one, is it? I haven’t seen that either.” Still, he laughs when I remind him of one line from the film: “Even old people don’t like old people.” That’s very true, he says, though he keeps in mind a quote from Clint Eastwood, for whom Jacobi played himself briefly in the 2010 drama Hereafter. “He was asked how he copes with age, and he replied: ‘I don’t let the old man in.’ Inevitably things drop off or seize up. Whenever you get a pain here or an ache there, you think: Oh dear, this is it.” Jacobi should know, having come through prostate cancer. “But you don’t let the old man in.”

Despite this pledge, he claims not to possess the stamina of his friend Ian McKellen, who last year took on Hamlet, when he was 82. “Rather him than me! Full marks, though.” Of all the parts Jacobi has played, that is the only one he can still remember in full. “I quote it endlessly,” he says. Indeed, it was the springboard for his entire career. At 18, he played Hamlet at school in Leyton, east London. That production went on to the Edinburgh fringe, catching the attention of the theatre critic Kenneth Tynan, who singled out this “dashing, wounded sulky-looking boy” and called him “a fine recruit … for modern prose drama”.

Jacobi studied at Cambridge then joined Birmingham Rep, where he was spotted by Laurence Olivier and recruited for the new National Theatre. (He and Olivier later became the only actors to receive both British and Danish knighthoods.) The day Jacobi turned 25, in 1963, he was back in Hamlet again, this time as Laertes, opposite Peter O’Toole. Shirley Bassey sang Happy Birthday to him at the afterparty. It was all an awfully long way from helping at his dad’s sweet shop in Chingford in east London. “Those were the days of rationing. I used to cut the coupons out. I wasn’t very good. I’d stand behind the counter and as soon as someone came in I’d yell, ‘Dad, you’ve got a customer,’ and I’d run out the back.”

His parents had cheered on his acting ever since his high-school Hamlet. “My mother said, ‘It was very nice but you ought to smile more in the curtain call.’ Three-and-a-half hours of Shakespeare and that was her only note. I wish all critics were like that!” There were never any expectations that he would follow in the family business. “I was a bit odd. I liked dressing up, that sort of thing. As a child, I ran down the streets in my mother’s wedding veil, and caught it on the privet.” His mother thought acting was a phase, which was also her response when he told her at 21 that he was in love with a man. A different man was also in love with Jacobi around the same time: McKellen, his Cambridge chum, was harbouring an unspoken crush. “I had no idea at all,” he says.

It is commonplace now to talk of pride in your sexuality; Jacobi and McKellen, who played a bitchy couple in the retro-styled 2013 sitcom Vicious, even served as grand marshals of the New York City Pride march in 2015. “There we were, sitting up in the car all the way down Fifth Avenue, doing a lot of this,” he says, twirling his hand in a royal wave. But pride wasn’t what he felt when he was growing up. “It was just the card I’d been dealt. When I was young, I didn’t know what ‘gay’ or ‘homosexual’ meant. I knew I was attracted to my own sex. That was a worry to start with: ‘I’m not supposed to be like this.’ Nothing to do with legality. It wasn’t really until university that I fell in love with somebody.” An upset with that boyfriend prompted him to come out to his mother. “Now she knew, and I didn’t need to say it again. Life went on.”

So, too, did acting. It was his performance as the stammering Roman emperor in I, Claudius, a runaway hit that was intelligent, savage and radical, that made him a star in 1976. What he remembers now is that it took an eternity to remove the makeup after the old-age scenes. “I’d submerge myself in a hot bath and gradually the entire thing would peel off. I had one of those wax faces in my cupboard for years.” There are whole trunks full of mementoes and memorabilia up in the attic. “One day, I’ll go through it all. My father saved a lot of newspaper cuttings and whatnot.” Perhaps there are toys, too, from In the Night Garden; Jacobi provided the lulling, melodious narration for every episode of that beguilingly surreal CBeebies series, making it sound like Edward Lear or Lewis Carroll. Mention it now and he launches into a roll call right there in the living room: “Upsy Daisy, Igglepiggle … Oh, that was a lovely one to do.”

For an actor not associated with malevolence, it is striking how easily and economically Jacobi can invoke it. He has played Hitler and Pinochet, and even came within sniffing distance of Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs. (It was down to Jacobi, Daniel Day-Lewis and the eventual star, Anthony Hopkins.) He has never been more insidious, though, than as Francis Bacon in John Maybury’s 1998 psycho-drama Love Is the Devil. Jacobi had only recently played Alan Turing on television in Breaking the Code, a role he originated on stage in 1986, and the contrast between that and Love Is the Devil alone is testament to his versatility. His Turing is emphatic, single-minded, vivid with curiosity. As Bacon, he is a shark in human skin.

I had hoped we might discuss that performance but he is foggy on the details. “Remind me,” he says. I mention his co-star, a pre-Bond Daniel Craig, and their sado-masochistic bedroom scenes with lit cigarettes. “Danny and I had great fun. But I don’t remember too much about it. I’m sorry.” He does recall attending a cabaret show by Anne Reid, his on-screen wife in Sally Wainwright’s joyous BBC comedy-drama Last Tango in Halifax. On stage, Reid referenced her sex scene with Craig in The Mother. Jacobi couldn’t resist calling out: “I did a film with Daniel Craig, too. And I went to bed with him twice!”

He has always complained in the past about his looks, writing in his 2013 autobiography, As Luck Would Have It: “Mine isn’t a face of which you think, ‘Ah, he’s suffered’ or ‘There’s something violent about him.’” Love Is the Devil is the exception that proves the rule. “I always longed to be chiselled,” he says now. “I was fluffy and round. Totally bland and uninteresting.” When did he stop feeling that way? “I didn’t.”

You would grow old waiting for him to sing his own praises. “I think I lost out in the ego stakes. I’m a shrinking violet. The only ego I’ve got is when I’m performing. Then I have the drive to succeed and not to fall flat on my face.” Michael Grandage, who directed him as King Lear in 2010, expressed concern for the way Jacobi puts himself through the mill each night, rejecting any shortcut to emotional effects. “It’s bloody tiring,” Jacobi says. “You certainly earn your money.” Then, a booming laugh: “Which, in the theatre, ain’t much!”

When he was last on stage in 2016, it was as Mercutio, with Richard Madden, 47 years his junior, as Romeo. The director, his friend Kenneth Branagh, convinced him that a long-in-the-tooth Mercutio could be a kind of Oscar Wilde figure, trading quips and crossing swords with the handsome young blades. “Toward the end, I would stand in the wings, terrified,” Jacobi admits. “Really frightened of going on. And that had been my life, you know? I suddenly got nervous. I wasn’t in control. And I thought: no. I can’t do my best like that, and an audience would pick up on it immediately.”

That part of his life now seems to be over. “I’ve got a feeling I won’t be on stage again,” he says faintly. “It’s not stage fright exactly. But I’m not comfortable like I used to be. And it’s far easier to do telly and films. They throw money at you for very little, and you get to do it until you do it right.” How does he feel, knowing he might never again set foot on stage? “Regretful. I do miss it. Whatever ‘it’ was, it’s faded.”

No more theatre, then. But what memories. I tell him I wish I had seen his Cyrano de Bergerac in 1983. “I adored doing that,” he says, suddenly upbeat. “I resisted it at first. I said, ‘I’m no swashbuckler.’”

Earlier I had asked him whether he had a catty side, like his character in Vicious. “Oh, I can be as camp as Chloe if you want me to be,” he replied. Nasty with it? “Not really. I’m a Libra: balanced, even-tempered and gentle.” Rather wonderfully, he proves otherwise just as our time together is ending. As we finish chatting about his RSC days, the conversation turns to Prospero, whom he played the year before Cyrano de Bergerac. Also in that production of The Tempest was a young upstart named Mark Rylance as Ariel. I ask whether it’s true, as rumour has it, that he felt Rylance upstaged him. Jacobi gives a look that could maim, if not kill. “He tried to,” he sniffs. “The little cunt.”

No sooner has the word left his mouth than he is giggling away, tickled pink at his own naughtiness. So, he does have claws after all. Hidden they may be. But they are there just the same.

A Bird Flew In is released on digital rental on 7 November and DVD and digital download on 12 December. Allelujah is released next year.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion