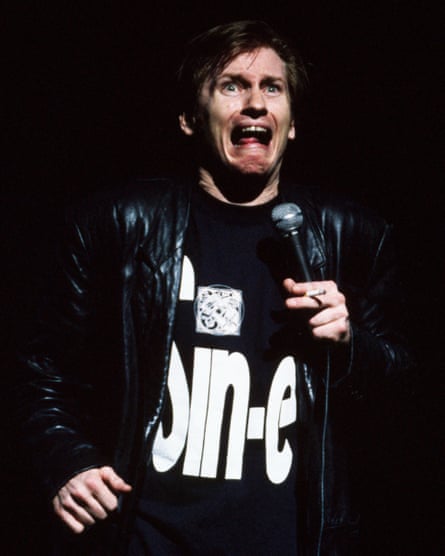

‘I’m an asshole,” sings Denis Leary in a signature number at the start of No Cure for Cancer, first televised 25 years ago this month. Still regularly cited among the great standup sets of all time, the show – performed off-Broadway, directed for TV by Ted Demme and released as a book and CD – launched Leary as a superstar, in the US at least. There was a follow-up, Lock’n’Load, along with countless movie roles and an Emmy nomination for his TV series Rescue Me. He’s still a fixture of the US entertainment scene and appeared last year in a double act with James Corden on The Late Late Show. Leary dressed as Bill Clinton, Corden as Hillary, and together they sang Trump’s an Asshole.

“No Cure for Cancer’s caustic spirit not only hasn’t waned in 25 years,” wrote one critic recently, “it’s been heightened considerably.” I can see why you’d argue that, but having just watched the special for the first time in years, I only partially agree. Yes, it’s a masterclass in standup technique. Yes, it inhabits a certain mindset with electrifying conviction, but the show seems more hymn to assholery than satire.

The comedian-as-asshole has a long lineage, and you can see why. It can be funny – or can, at least, provoke a kind of appalled laughter – to see someone cast off civility on stage, to unleash the raging id the rest of us spend our lives keeping under control. You could cite early-career Brendon Burns or Jim Jeffries: self-styled bad boys ramping up the boorish for our entertainment. Like those early Burns and Jeffries shows, I find Leary’s set off-puttingly macho and aggressive. And cynical. Where others see (and where Leary presumably intends) sendup, I can’t see past the relish with which Leary animates his thuggish persona, shouting the odds about non-smokers, vegetarians, the French.

The issue isn’t that No Cure has dated: I had the same reservations when I first saw it. Twenty-five years on, you could claim equally that Leary’s set hasn’t aged well, and that, by contrast, it’s never been more topical. It’s certainly not unusual in 2018 to see a middle-aged male comic lamenting PC, modernity and (Leary doesn’t use the word – but he means it) snowflakes. Maybe, in our snowflake era, No Cure would attract more flak for its mocking jokes about suicides. But equally it might resonate more in an age where angry white guys hating on the present day have gone mainstream.

So, to quote Leary’s lyrics, would the sort of “regular Joe with a regular job … your average white suburbanite slob” who roots for Trump find himself and his world view undermined or endorsed by No Cure? I’d say the latter, because I can discern hardly any critical distance between Leary and the persona (“life sucks, get a fuckin’ helmet, alright?”) he’s using on stage. No Cure barely registers as social satire. It’s far more effective as a standup version of the “eight-balls” Leary rants about in its opening sections: a crack-cocaine comic rush, a fever dream, a sonic overload from an act in which punchlines arrive less often as words than as very loud noises.

In those terms, No Cure is undeniably a striking set. Leary is in gripping command of his standup stylings, switching on a dime from psycho-on-the-edge to barking Tasmanian devil, sucking hungrily on cigarettes, swaggering and (self-consciously) cool. Too bad if we can’t quite get out of our heads the similarities to his (ex-)friend Bill Hicks – accusations of plagiarism followed Leary throughout his subsequent career. Hicks – who died of pancreatic cancer in 1994 – cried foul when he first saw Leary’s breakout set, and ever since, a joke has done the rounds asking: “Why is Denis Leary a star while Bill Hicks is unknown?” Answer: “Because there’s no cure for cancer.”

I certainly prefer Hicks’s work. There’s more tonal variety, and Hicks has a soulfulness, self-irony and subversive streak that’s absent from No Cure. You’re never in any doubt where Hicks stands vis-a-vis jock culture. The same goes for asshole-comics like Jerry Sadowitz and Doug Stanhope, who play obnoxious without ever giving obnoxiousness a free pass. The idea that there are hidden depths to Leary’s persona rests on the third quarter of No Cure, when he takes a seat, has a deep breath, and gets contemplative about his alpha male Irish dad. It’s a strong section – at least until the earnest and sentimental conclusion, which Leary addresses to his two-year-old son.

Other comics have more successfully integrated the emotional significance with the jokes. Here, the gears crunch loudly as Leary moves from one to the other. To his credit, that moment of intimacy must have seemed more radical than it does a quarter century later, when so many standups wear their hearts on their sleeve. No Cure for Cancer is still worth watching in 2018: still pungent, still pertinent, and the smoke still makes your eyes sting.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion