Marvel Comics is an American comic book line published by Marvel Entertainment, Inc. Affectionately called the House of Ideas by the fan press, Marvel’s best-known comics titles include Fantastic Four, The Amazing Spider-Man, The Incredible Hulk, Iron Man, Daredevil, Thor, Captain America, and X-Men. Most of Marvel’s fictional characters reside in the Marvel Universe.

Since the 1960s, it has been one of the two largest American comics companies, along with DC Comics. Located in New York City, Marvel has been successively headquartered in the McGraw-Hill Building on West 42nd Street (where it originated as Timely Comics in 1939); in suite 1401 of the Empire State Building; at 635 Madison Avenue (the actual location, though the comic books’ indicia listed the parent publishing-company’s address of 625 Madison Ave.); 575 Madison Avenue; 387 Park Avenue South; 10 East 40th Street; and 417 Fifth Avenue.

Timely Comics

Marvel Comics was founded by established pulp-magazine publisher Martin Goodman in 1939 as an eventual group of subsidiary companies under the umbrella name Timely Comics. Its first publication was Marvel Comics #1 (Oct. 1939), featuring the second appearance of Carl Burgos’ android superhero, the Human Torch, and the first generally available appearance of Bill Everett’s mutant anti-hero Namor the Sub-Mariner. The contents of that sales blockbuster were supplied by an outside packager, Funnies, Inc., but by the following year Timely had a staff in place.

Marvel Comics was founded by established pulp-magazine publisher Martin Goodman in 1939 as an eventual group of subsidiary companies under the umbrella name Timely Comics. Its first publication was Marvel Comics #1 (Oct. 1939), featuring the second appearance of Carl Burgos’ android superhero, the Human Torch, and the first generally available appearance of Bill Everett’s mutant anti-hero Namor the Sub-Mariner. The contents of that sales blockbuster were supplied by an outside packager, Funnies, Inc., but by the following year Timely had a staff in place.

The company’s first editor, the writer-artist Joe Simon, teamed with soon-to-be industry legend Jack Kirby to create one of the first patriotically themed superheroes, Captain America, in Captain America Comics #1 (March 1941). It, too, proved a major sales hit.

While no other Timely character would be as successful as these “big three”, some notable heroes — many continuing to appear in modern-day retcon appearances and flashbacks — include the Whizzer, Miss America, the Destroyer, the original Vision, and Paul Gustavson’s Angel. Timely also published one of humor cartoonist Basil Wolverton’s best-known features, Powerhouse Pepper.

Atlas Comics (1950s)

Sales of all comic books declined drastically in the post-war era as the superheroic übermensch archetype popular during the Depression and the war years went out of fashion. Like other comics companies, Timely — generally known as Atlas Comics in the 1950s — followed pop-cultural trends with a variety of genres, including funny animals, Western, horror, war, crime, humor, romance, spy fiction and even medieval adventure, all with varying degrees of success. An attempted superhero revival from 1953 to 1954, with the Human Torch, the Sub-Mariner and Captain America, failed.

From 1952 to late 1956, Goodman distributed his comics to newsstands through his self-owned distributor, Atlas. He then switched to American News Company, the nation’s largest distributor and a virtual monopoly — which shortly afterward lost a Justice Department lawsuit and discontinued the business. As historian and author Gerard Jones explains, the company in 1956

…had been found guilty of restraint of trade and ordered to divest itself of the newsstands it owned. Its biggest client, George Delacorte, announced he would seek a new distributor for his Dell Comics and paperbacks. The owners of American News estimated the effect that would have on their income. Then they looked at the value of the New Jersey real estate where their headquarters sat. They liquidated the company and sold the land. The company … vanished without a trace in the suburban growth of the 1950s.

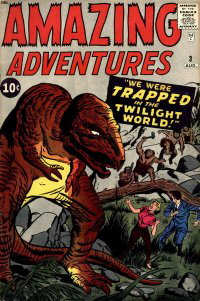

The final comic to bear the Atlas globe logo was Dippy Duck #1, the company’s only release with an October 1957 cover date. The first comic book labeled “Marvel Comics” was the science-fiction anthology Amazing Adventures #3, which showed the “MC” box on its cover. Cover-dated August 1961, it was published May 9, 1961.

Amazing Adventures Vol. 1, #3 (Aug. 1961), the first comic labeled “Marvel Comics” (MC below Comics Code seal). Cover art by Jack Kirby (penciler) & Dick Ayers (inker).At that point, Goodman attempted a new direction by following the current drive-in science fiction-movie trend, launching or revamping six titles to offer that genre of story: Strange Worlds #1; World of Fantasy #15; Strange Tales #67; Journey into Mystery #50; Tales of Suspense #1; and Tales to Astonish #1. Their space-fantasy tales proved unsuccessful, and by the end of 1959, most of these titles (Strange Worlds and World of Fantasy being cancelled) were devoted to B-movie monsters. Most featured a line-up of Jack Kirby-drawn stories (often inked by Dick Ayers) followed by Don Heck’s atmospheric rendering of jungle/prison escapes and weird adventures, or stories by artists such as Paul Reinman or Joe Sinnott, followed by a Stan Lee-Steve Ditko twist-ending bagatelle, which were sometimes daringly self-reflexive.

Amazing Adventures Vol. 1, #3 (Aug. 1961), the first comic labeled “Marvel Comics” (MC below Comics Code seal). Cover art by Jack Kirby (penciler) & Dick Ayers (inker).At that point, Goodman attempted a new direction by following the current drive-in science fiction-movie trend, launching or revamping six titles to offer that genre of story: Strange Worlds #1; World of Fantasy #15; Strange Tales #67; Journey into Mystery #50; Tales of Suspense #1; and Tales to Astonish #1. Their space-fantasy tales proved unsuccessful, and by the end of 1959, most of these titles (Strange Worlds and World of Fantasy being cancelled) were devoted to B-movie monsters. Most featured a line-up of Jack Kirby-drawn stories (often inked by Dick Ayers) followed by Don Heck’s atmospheric rendering of jungle/prison escapes and weird adventures, or stories by artists such as Paul Reinman or Joe Sinnott, followed by a Stan Lee-Steve Ditko twist-ending bagatelle, which were sometimes daringly self-reflexive.

Marvel also expanded its line of girl-humor titles during this time, introducing Kathy (“the teen-age tornado!”) (Oct. 1959) and the short-lived Linda Carter, Student Nurse (Sept. 1961).

1960s

In the wake of DC Comics’ success reviving superheroes in the late 1950s and early 1960s, particularly with The Justice League of America, Marvel decided to follow suit.

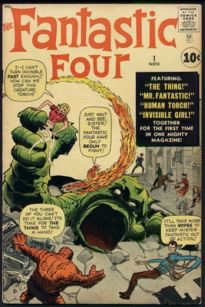

The Fantastic Four #1 (Nov. 1961), the cornerstone of Marvel and the introduction of a new style of superhero. Cover art by Jack Kirby (penciler) & Dick Ayers (inker; unconfirmed).Editor/writer Stan Lee and freelance artist Jack Kirby created the Fantastic Four, vaguely reminiscent of adventuring quartet the Challengers of the Unknown, which Kirby had created for DC in 1957. Eschewing such comic-book tropes as secret identities and even costumes at first, having a monster as one of the heroes, and having its characters bicker and complain in what was later called a “superheroes in the real world” approach, the series, as noted in countless comic-book histories (see References, below), represented a change that helped to make both it and the approach a great success. Marvel began publishing further superhero titles featuring such heroes and anti-heroes as the Hulk, Spider-Man, Thor, Ant-Man, Iron Man, the X-Men, and Daredevil, and such memorable antagonists as Doctor Doom, Magneto, Galactus, the Green Goblin and Doctor Octopus. The most successful new series was The Amazing Spider-Man, by Lee and Ditko. Marvel even lampooned itself, and other comics companies, in a parody comic, Not Brand Echh (a play on Marvel’s dubbing of other companies as “Brand Echh”, a la the then-common phrase “Brand X”).

The Fantastic Four #1 (Nov. 1961), the cornerstone of Marvel and the introduction of a new style of superhero. Cover art by Jack Kirby (penciler) & Dick Ayers (inker; unconfirmed).Editor/writer Stan Lee and freelance artist Jack Kirby created the Fantastic Four, vaguely reminiscent of adventuring quartet the Challengers of the Unknown, which Kirby had created for DC in 1957. Eschewing such comic-book tropes as secret identities and even costumes at first, having a monster as one of the heroes, and having its characters bicker and complain in what was later called a “superheroes in the real world” approach, the series, as noted in countless comic-book histories (see References, below), represented a change that helped to make both it and the approach a great success. Marvel began publishing further superhero titles featuring such heroes and anti-heroes as the Hulk, Spider-Man, Thor, Ant-Man, Iron Man, the X-Men, and Daredevil, and such memorable antagonists as Doctor Doom, Magneto, Galactus, the Green Goblin and Doctor Octopus. The most successful new series was The Amazing Spider-Man, by Lee and Ditko. Marvel even lampooned itself, and other comics companies, in a parody comic, Not Brand Echh (a play on Marvel’s dubbing of other companies as “Brand Echh”, a la the then-common phrase “Brand X”).

Marvel’s comics were noted for focusing on characterization to a greater extent than most superhero comics before them. This was true of The Amazing Spider-Man, in particular. Its young hero suffered from self-doubt and mundane problems like any other teenager. Marvel superheroes are often flawed, freaks, and misfits, unlike the perfect, handsome, athletic heroes found in previous traditional comic books. Some Marvel heroes looked like villains and monsters. In time, this non-traditional approach would revolutionize comic books.

Comics historian Peter Sanderson wrote that in the 1960s,

DC was the equivalent of the big Hollywood studios: After the brilliance of DC’s reinvention of the superhero … in the late 1950s and early 1960s, it had run into a creative drought by the decade’s end. There was a new audience for comics now, and it wasn’t just the little kids that traditionally had read the books. The Marvel of the 1960s was in its own way the counterpart of the French New Wave…. Marvel was pioneering new methods of comics storytelling and characterization, addressing more serious themes, and in the process keeping and attracting readers in their teens and beyond. Moreover, among this new generation of readers were people who wanted to write or draw comics themselves, within the new style that Marvel had pioneered, and push the creative envelope still further.

Lee became one of the best-known names in comics, with his charming personality and relentless salesmanship of the company. His “voice” permeates the stories, the letters and news pages, and even the hyperbolic house ads of many of the Marvel Comics of the first half of the 1960s: his sense of humor and generally lighthearted manner, and the exaggerated depiction of the Bullpen (Lee’s name for the staff) as one big, happy family. The artists — who eventually co-plotted the stories based on the busy Lee’s rough synopsis or even simple spoken concept, in what became known as the Marvel Method — contributed greatly to Marvel’s product and success. Kirby in particular is generally credited for many of the cosmic ideas and characters of Fantastic Four and The Mighty Thor, such as the Watcher, the Silver Surfer and Ego the Living Planet, while Steve Ditko is recognized as the driving artistic force behind the moody atmosphere and street-level naturalism of Spider-Man and the surreal atmosphere of Dr. Strange. Lee, however, continues to receive credit for his well-honed skills at dialogue and story sense, for his keen hand at choosing and motivating artists and assembling creative teams, and for his uncanny ability to connect with the readers.

In 1968, company founder Martin Goodman sold Marvel Comics and his other publishing businesses to the Perfect Film and Chemical Corporation. It grouped these businesses in a subsidiary called Magazine Management Co. Goodman remained as publisher.

1970s

In 1970, Stan Lee saw the opportunity to market a British audience without using reprinted American material. In October 1970, Marvel created “a British hero for British people”, Captain Britain, first released exclusively in Britain and later in America.

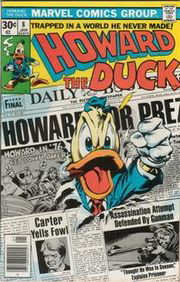

Howard the Duck #8 (Jan. 1977). Art by Gene Colan and Steve LeialohaIn 1971, Marvel Comics editor-in-chief Stan Lee was approached by the United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare to do a comic book story about drug abuse. Lee agreed and wrote a three-part Spider-Man story portraying drug use as dangerous and unglamorous. However, the industry’s self-censorship board, the Comics Code Authority, refused to approve the story because of the presence of narcotics, deeming the context of the story irrelevant. Lee, with Goodman’s approval, published the story regardless in The Amazing Spider-Man #96-98 (May-July 1971), without CCA approval. The storyline was well-received and the CCA’s argument for denying its approval was criticized as counterproductive. The Code was subsequently revised the same year.

Goodman retired as publisher in 1972 and was succeeded by Lee, who stepped aside from running day-to-day operations at Marvel. A series of new editors-in-chief oversaw the company during another slow time for the industry. Once again, Marvel attempted to diversify, and with the updating of the Comics Code achieved moderate success with titles themed to horror (Tomb of Dracula), martial arts, (Shang-Chi: Master of Kung Fu), sword-and-sorcery (Conan the Barbarian, Red Sonja), satire (Howard the Duck) and science fiction (“Killraven” in Amazing Adventures). Some of these were published in larger-sized black-and-white magazines, targeted for mature readers. Marvel was able to capitalize on its successful superhero comics of the previous decade by acquiring a new newsstand distributor and greatly expanding its comics line. Even more importantly, during a time when the price and format of the standard newsstand comic were in flux, Marvel captured a significant piece of DC’s market share by offering a lower-priced product with a higher distributor discount.

In 1973, Perfect Film and Chemical Corporation changed its name to Cadence Industries, which in turn renamed Magazine Management Co. as Marvel Comics Group. Goodman, now completely disconnected from Marvel, created a new company called Atlas/Seaboard Comics in 1974, reviving Marvel’s old Atlas name, but this project lasted only a year-and-a-half.

In the mid-1970s, Marvel was affected by a decline of the newsstand distribution network. Cult hits such as Howard the Duck were the victims of the distribution problems, with some titles reporting low sales when in fact they were being resold at a later date in the first specialty comic-book stores. An attempt by Marvel to buy DC[citation needed] was frustrated by DC’s refusal to sell its entire library of characters (wanting to retain control of Superman and Batman), and DC was later folded into Warner Communications by owner Kinney National Company.

In the mid-1970s, Marvel was affected by a decline of the newsstand distribution network. Cult hits such as Howard the Duck were the victims of the distribution problems, with some titles reporting low sales when in fact they were being resold at a later date in the first specialty comic-book stores. An attempt by Marvel to buy DC[citation needed] was frustrated by DC’s refusal to sell its entire library of characters (wanting to retain control of Superman and Batman), and DC was later folded into Warner Communications by owner Kinney National Company.

By the end of the decade, Marvel’s fortunes were reviving, thanks to the rise of direct-market distribution (selling through those same comics-specialty stores instead of newsstands) and the sales increase of previously borderline books — such as the canceled ’60s title The Uncanny X-Men, revived to become a hit series under the team of writer Chris Claremont and artist John Byrne, or the more naturalistic, urban-crime superhero comic Daredevil, by writer/artist Frank Miller.

1980s

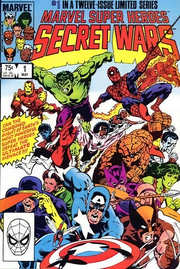

Marvel Super Heroes Secret Wars #1 (May 1984). Art by Mike ZeckBy the 1980s, one-time DC wunderkind Jim Shooter was Marvel’s Editor-in-Chief. Although a controversial personality, Shooter cured many of the procedural ills at Marvel (including repeatedly missed deadlines) and oversaw a creative renaissance at the company. This renaissance included institutionalizing creator royalties, starting the Epic imprint for creator-owned material in 1982, and launching a brand-new (albeit ultimately unsuccessful) line named New Universe, to commemorate Marvel’s 25th anniversary, in 1986. However, Shooter was responsible for the introduction of the company-wide crossover (Contest of Champions, Secret Wars) and was accused by many creators, especially near the end of his tenure, of exercising his job in a draconian manner and interfering with the writers’ creative process.

Marvel Super Heroes Secret Wars #1 (May 1984). Art by Mike ZeckBy the 1980s, one-time DC wunderkind Jim Shooter was Marvel’s Editor-in-Chief. Although a controversial personality, Shooter cured many of the procedural ills at Marvel (including repeatedly missed deadlines) and oversaw a creative renaissance at the company. This renaissance included institutionalizing creator royalties, starting the Epic imprint for creator-owned material in 1982, and launching a brand-new (albeit ultimately unsuccessful) line named New Universe, to commemorate Marvel’s 25th anniversary, in 1986. However, Shooter was responsible for the introduction of the company-wide crossover (Contest of Champions, Secret Wars) and was accused by many creators, especially near the end of his tenure, of exercising his job in a draconian manner and interfering with the writers’ creative process.

In 1981 Marvel purchased the DePatie-Freleng Enterprises animation studio from famed Looney Tunes director Friz Freleng and his business partner David H. DePatie. The company was renamed Marvel Productions and it produced well-known animated TV series and movies featuring such characters as G.I. Joe, The Transformers, Jim Henson’s Muppet Babies, and such TV series as Dungeons & Dragons, as well as cartoons based on Marvel characters, including Spider-Man and His Amazing Friends.

In 1986, Marvel was sold to New World Entertainment, which within three years sold it to MacAndrews and Forbes, owned by Revlon executive Ronald Perelman. Perelman took the company public on the New York Stock Exchange and oversaw a great increase in the number of titles Marvel published. As part of the process, Marvel Productions sold its back catalog to Saban Entertainment (acquired in 2001 by Disney ), and Marvel management closed the animation studio, opting to outsource.

1990s

Peter Parker: Spider-Man #1 (Aug. 1990; black & gold edition), one of many spin-offs of The Amazing Spider Man. Cover art by Todd McFarlane.Marvel earned a great deal of money and recognition during the early decade’s comic-book boom, launching the highly successful 2099 line of comics set in the future (Spider-Man 2099 etc.) and the creatively daring though commercially unsuccessful Razorline imprint of superhero comics created by novelist and filmmaker Clive Barker. Yet by the middle of the decade, the industry had slumped and Marvel filed for bankruptcy amidst investigations of Perelman’s financial activities regarding the company.

Peter Parker: Spider-Man #1 (Aug. 1990; black & gold edition), one of many spin-offs of The Amazing Spider Man. Cover art by Todd McFarlane.Marvel earned a great deal of money and recognition during the early decade’s comic-book boom, launching the highly successful 2099 line of comics set in the future (Spider-Man 2099 etc.) and the creatively daring though commercially unsuccessful Razorline imprint of superhero comics created by novelist and filmmaker Clive Barker. Yet by the middle of the decade, the industry had slumped and Marvel filed for bankruptcy amidst investigations of Perelman’s financial activities regarding the company.

In 1990, Marvel begin selling Marvel Universe Cards with trading card maker Impel. These were collectible trading cards that featured the characters and events of the Marvel Universe, which would spawn several more series of cards and imitations by DC.

Marvel in 1992 acquired Fleer Corporation, known primarily for its trading cards, and shortly thereafter created Marvel Studios, devoted to film and TV projects. Avi Arad became director of that division in 1993, with production accelerating in 1998 following the success of the film Blade.

In 1994, Marvel acquired the comic book distributor Heroes World to use as its own exclusive distributor. As the industry’s other major publishers made exclusive distribution deals with other companies, the ripple effect resulted in the survival of only one other major distributor in North America, Diamond Comic Distributors Inc..

Investor Carl Icahn attempted to take control of Marvel, but in 199 7, after protracted legal battles, control landed in the hands of Isaac Perlmutter, owner of the Marvel subsidiary Toy Biz. With his business partner Avi Arad, publisher Bill Jemas, and editor-in-chief Bob Harras, Perlmutter helped revitalize the comics line.

Creatively and commercially, the ’90s were dominated by the use of gimmickry to boost sales, such as variant covers, cover enhancements, regular company-wide crossovers that threw the universe’s continuity into disarray, and even special swimsuit issues . In 1996, Marvel had almost all its titles participate in the Onslaught Saga, a crossover that allowed Marvel to relaunch some of its flagship characters, such as the Avengers and the Fantastic Four, in the Heroes Reborn universe, in which Marvel defectors Jim Lee and Rob Liefeld were given permission to revamp the properties from scratch. After an initial sales bump, sales quickly declined below expected levels, and Marvel discontinued the experiment after a one-year run; the characters returned to the Marvel Universe proper. In 1998, the company launched the imprint Marvel Knights, taking place within Marvel continuity; helmed by soon-to-become editor-in-chief Joe Quesada, and featuring tough, gritty stories showcasing such characters as the Inhumans, Black Panther and Daredevil, it achieved substantial success.

2000s