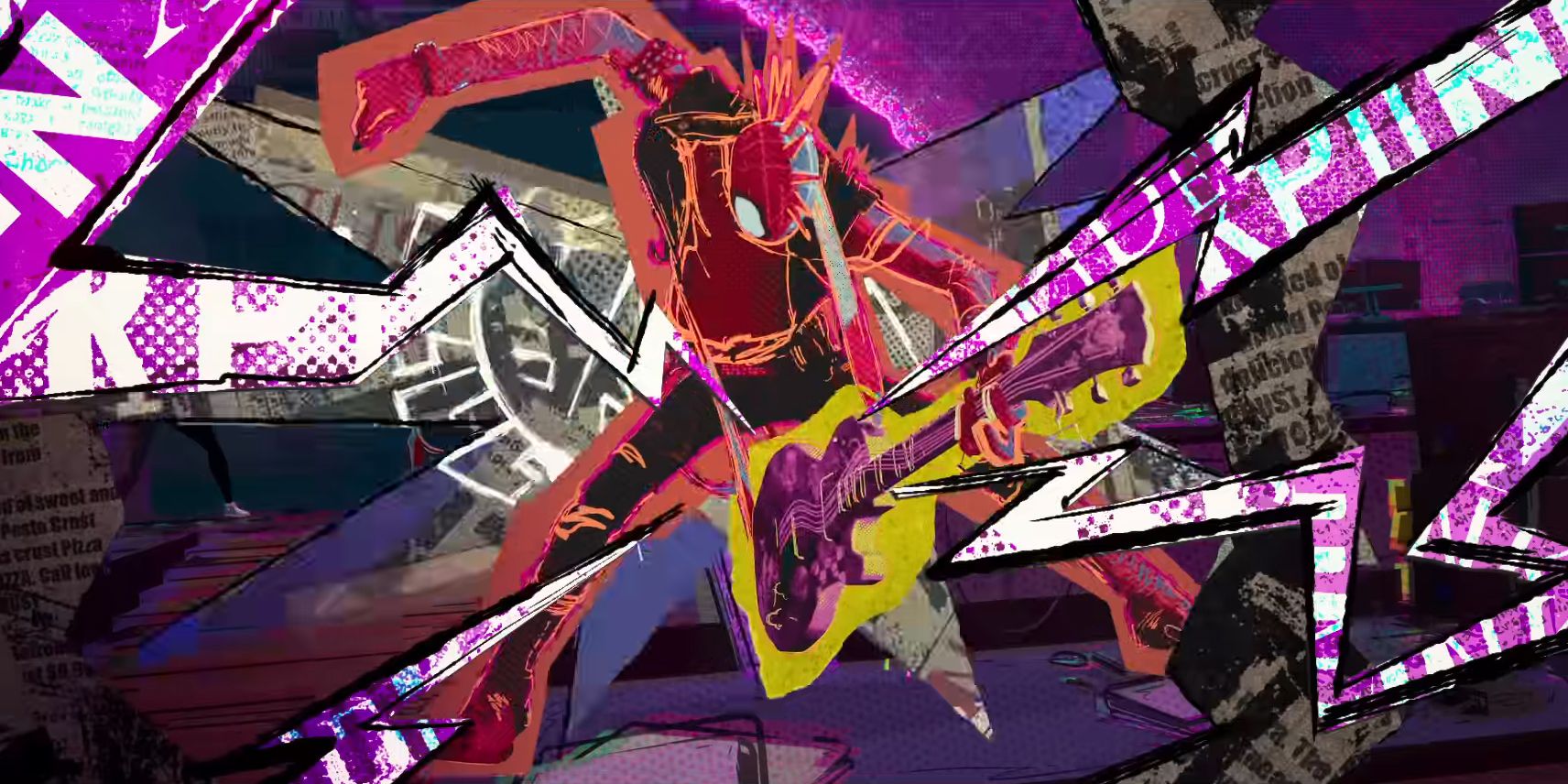

A film's score can make or break important emotional beats in a movie, and composer Daniel Pemberton is among the greats when it comes to film scores. Following the massive success of Sony Pictures’ Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse, Collider’s Steve Weintraub got the chance to sit down with Pemberton during the Mediterrane Film Festival to pick his brain on everything from the inevitable influence of AI in entertainment to Michael Mann’s long-anticipated Heat 2 and composing the music for Ferrari in a week.

Pemberton began his career in television and skyrocketed when, for his second feature film ever, the composer worked alongside Ridley Scott on The Counselor—a favorite of Guillermo del Toro’s, he tells Weintraub. Since then, he’s gone on to earn an Emmy, multiple Golden Globe nominations, and an Academy Award nomination for his work on Aaron Sorkin’s The Trial of the Chicago 7. Other notable features you’ll hear Pemberton’s work on include The Man from U.N.C.L.E., Birds of Prey, and Ocean’s Eight.

During their conversation, Pemberton shares his thoughts on the pros and cons of AI within the industry and otherwise, working with Mick Jagger for Apple TV’s Slow Horses, the influences and Easter eggs to look out for in Across the Spider-Verse, what it’s like working with Guy Ritchie, and scoring Mann’s upcoming Ferrari, starring Adam Driver, in a week. For this and tons more, check out the full interview below.

COLLIDER: I’ve been a fan of yours for a while, you've done a lot of cool things. If someone has never heard anything you've composed, any movie, whatever it may be, what's the thing you want them to start with?

DANIEL PEMBERTON: I'd probably say King Arthur [Legend of the Sword] because, for me, it's like trying to see how you can kind of subvert what a traditional film score can sound like on a big blockbuster and how experimental you can be within that idiom because the bigger the film, the harder it is to push the boundaries of what it can sound and feel like. I think with King Arthur, we ended up with this crazy score which features more of me than maybe any score I'll ever do because it’s got me breathing, got me screaming… I did this thing where I had to explain that when I recorded that score, I had to actually phone my neighbor up who lived above me to tell them I'm going to be screaming for about 15, 20 minutes. “Don't worry, I'm just recording something.” I think the mix of experimentation and the kind of viscerality and the rawness of that score is probably a good starting point.

Yeah, that's a good score. I'm a fan of Guy Ritchie.

PEMBERTON: You haven't worked with him. [Laughs]

I've been around him, but no, I haven't worked with him.

PEMBERTON: Working with him is a different experience. Let's put it that way.

I've been asking this of everyone. This is a bigger, heavier question than I normally do this early in an interview, but everyone's talking about AI right now and I'm just curious what your take is on it? Are you scared of AI or are you looking forward to seeing how it can help you with your work? What are your thoughts? Because it does seem to me that we're on the precipice of a whole new thing.

PEMBERTON: I think AI has applications within it which are incredibly exciting and applications within it which incredibly terrifying. The thing that's difficult for me is I grew up– I actually used to be a journalist. I used to write about tech, and I used to write about the internet in the ‘90s. I had a website in, like, ‘94, which at that time was kind of crazy shit. I met a guy called Daniel Pemberton who literally emailed me because we had the same name and I met him, he's a construction designer, I met him at Warner Brothers like 25 years later. Weird story, but very moving. But I went from watching the internet be this utopian ideal of how we can share information and reset the way the world was ordered into a terrible dystopian version of just the worst instincts of humanity being amplified.

I think about it; if you think you've got this device in your pocket that has access to all the world's music, all the world's knowledge, you'd think people, society would have gotten amazing, but I sort of feel it got worse in terms of– You know, there’s great stuff about the internet, but the bad stuff’s won out a lot of the time. My worry with AI is, while I think that there's gonna be really great usages of it, the trouble is the people. The corporations are more interested in, like I say, reheating meals. I talked about this, I talk about cinema. It's like the best cinema is stuff that's new and different, and a lot of cinema recently has been just reheating the same dish over and over again, and AI is the ultimate reheater of dishes. It's like, “Here's the cooking you liked before that people say they like. We're just going to reheat it and do it this way.”

I thought about this with regards to [Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse] because one of the most interesting things about Spider-Verse, I think, is how kind of anti-AI the film is in terms of it's such a reflection of people's human experiences with art and creativity. I even look at the score; the first [Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse], and the new one, it is the way it is because of experiences I've had through my life. I went to some hip-hop clubs when I was a teenager, like 18, and I saw record scratching for the first time, and that blew my mind. Like proper experimental record scratching where I was like, “This is something I've never seen done to this level, and this is like an amazing piece of artistry. I'd love to use this in a musical way.” I kept that in my head for like 15 years until the right moment, which was Spider-Verse. I was like, “Finally, I can then use this in a score,” where we basically recorded orchestral parts, put them onto vinyl, and then re-scratch them back into the score, which is why the score feels very different. And the same thing, I went to these techno clubs when I was 16 and got exposed to really extreme electronic music. And again, in the new Spider-Verse, when we go to Miguel’s 2099 world, all those experiences I've had at that age I decided to pull upon and put into the score.

Those are decisions that I've made based on my own personal cultural experiences, and that's hopefully what makes the Spider-Verse score not feel like any other score that's out there. I think AI could be interesting in terms of helping me create a wider range of ideas within that, but as we saw with the internet, we have the world's knowledge in our pocket and we use it mainly to post photos of people's feet on the beach or sipping cocktails. The sort of power of capitalism to reduce things to its– Capitalism doesn't like art unless there's a value attached, and we as a society don't really like art when there’s a value attached.

Weird story: I remember Bansky, who used to graffiti a lot near where I lived, did this piece called Checkbook Capitalism. He had done this huge piece around this scaffolding hoarding near the Tate—this is when no one cared about Banksy—and the council one day did this thing and said, “We’re cleaning up the neighborhood,” and they had a photo of the Banksy piece, which had been there for like months and months and months. They had a photo of how they painted over it gray. I was so angry that they were saying how proud they were that they got rid of this piece. I actually wrote them a letter saying, “As a constituent, I cannot believe you have painted over this interesting critique of capitalism, and you're proud of that. You’ve used my money to do it, and you're showing off about it.” I was like, “If this guy's work was worth millions of pounds, you would bend over backwards to preserve it.” And then years later, his work is worth millions of pounds, which I never thought would happen, and councils now just bend over backwards if it turns up, and that's because there's a value attached.

I’m sort of going off on crazy tangents here, but the power of art, the most powerful bits of art, don't always have a value attached. I think capitalism pushes everything to look through the value, and AI is a very powerful way to really focus in on where value is created and crowd out everything else. I think the biggest problem is the crowding out of other ideas.

Yeah, the biggest thing, and I don't mean to have this go into a deep dive into AI, but I do believe that there is a lot of good. For example, how doctors can use AI to research new medicines.

PEMBERTON: Yeah, I have a friend who's– So, I basically know a guy in AI who's like an AI gazillionaire, and I saw him three weeks ago in LA. I haven't seen him for ages, and so I'm like, “Okay, tell me what you're up to.” And I’m like, “Oh good, you're doing the good AI. I feel better about this.” He's built this whole infrastructure which is basically taking every medical journal and being able to take diagnosis information from doctors because one of the hardest things in medicine is actually just accurate information, and it mines everything a doctor puts in and gives them so much detail. It's really fascinating, and that side of stuff is amazing.

I've read about how AI is creating new medicines that they're testing that are going to solve really big problems because they can do the computational things that would take us forever. They just zoom through it, and that's amazing. And I do think that someone in, like, Lincoln, Nebraska will be able to use AI to break in by creating something cool, but they're gonna shape it with their brain using the AI technology. But then I think about the studios and what they're going to do.

PEMBERTON: I think as a technology, AI could be artistically unbelievably exciting. The thing that is problematic is the noise that's going to be created by corporation studios to crowd out and destroy that stuff. Even if you look at something like Spotify, which is in some ways an amazingly democratic force for music, even though I have loads of issues with Spotify, one of the things that’s interesting is anyone anywhere in the world can get their music on that platform relatively easily, and they can be as accessible as a new Beyoncé record. But that whole market is controlled by the majors; they control the playlists, they gatekeep, they've created this form of gatekeeping that is even more extreme than it was before, and that's gonna be the big issue.

We're gonna switch off this, but we're also not even talking about the fact that AI in five years is going to diagnose and be able to replicate what hit songs are. There's some scary shit coming because of the power of the computer, and being able to just look at 1,000 hit songs and break them down by beats, how often things happen, and it's going to be rinse-and-repeat.

PEMBERTON: Like I say, it's a reheater. It's a reheater of the same meal.

Exactly.

PEMBERTON: If you look at all the often-great works of art that change things, you look at The Beatles, [Igor] Stravinsky, these would not come through that system. You’d get things that feel like more of the same. And there are definitely things that are interesting, like, what if we put Stravinsky with The Beatles with the sound of a tube train? Maybe that's going to create something amazing. But then the problem is you're going to drown in noise. There's going to be constant [noise].

There's stuff to do with film production, which is both very exciting and very scary. I personally think it's very overall kind of terrifying from a more– Creativity exists because people can make a living out of creativity. People can always be creative, but when people can make a living out of creativity, creativity gets incredibly exciting. All the great works are often done because there is some sort of financial support behind them. Even like Mozart, if Mozart wasn't getting paid to write his pieces or perform for people, he probably wouldn't keep writing that music and have to do something else or have the time and space to do it.

Completely. Also, think about this, there are a lot of corporations that are currently buying life rights. At some point in the not-so-distant future, someone is going to come out with Humphrey Bogart, Bruce Lee and Marilyn Monroe in a movie together.

PEMBERTON: I always used to joke that the way the movies are going—this is a while ago now, but I can see it happening—they're going to bring out a movie that's basically James Bond teaming up with Predator and Indiana Jones to take on RoboCop and Mickey Mouse, who are driving the Batmobile around 1920s New York. And I'd be like, “I'd probably watch that movie.” [Laughs]

The scary part is I would watch that movie. But that is the problem is that there's going to be a period of time with AI where the product will come out, it will be new and exciting, it's going to hook people, but then eventually, people are going to want to go analog again. Anyway, let's jump in if you don't mind because I could talk about this for an hour. So, you did The Counselor with Ridley Scott. That was your first film, I believe?

PEMBERTON: I did a film before that called The Awakening with Nick Murphy, which no one really caught. But then, obviously one person did, which totally changed my career. Actually, I just saw him a few hours ago. He’s with the Gladiator 2 set. It's fucking insane. We're not doing on the AI thing, but the Gladiator 2 set is all physical. It's insane. That's one of those things where you're like, “This is amazing to see this level of artistry across everything.” He is so fucking on it, and his energy is fantastic.

I begged them to let me go to Gladiator 2, even under an NDA, and I could not. I took photos from a distance. That's the closest I could get, but I'm very, very excited. Anyway, so the thing about The Counselor was with a lot of Ridley's movies, they get shorter in the editing room. When you were working on that, did you ever see a way longer cut of that movie?

PEMBERTON: Oh yeah, there's loads of different cuts of that movie. There's like a whole character that they had to cut out for length.

I think there's a longer cut on Blu-ray, but I've heard it's not even close to what could be.

PEMBERTON: Yeah, there are whole extra story beats that aren't in there. That film is interesting. I have a lot of love for that film because it meant so much to me. It's so interesting the responses from people where they’re just like, “I fucking hate that movie,” or people love it. Guillermo del Toro loves that movie. Ridley was like, “There’s this crazy Mexican guy who's watching it like every day.” Then I find it out, and I’m like, “Oh, you mean Guillermo del Toro?”

That’s funny. I wonder which version Guillermo is watching, if it's the longer cut or the actual cut?

PEMBERTON: Yeah, I don't know.

I'm gonna ask him about this. Jumping on to the next thing, which score that you worked on ended up being the one where you're like, “Fuck this. I'm quitting this project?” Or has that ever happened to you?

PEMBERTON: Luckily, that hasn't happened to me yet. I've had some very difficult processes. King Arthur, in particular, was a very difficult process, but you just keep on. Guy Ritchie once said I've got the thickest skin of anyone he's ever met, so that tells you what you need to know about that project. [Laughs]

That's funny. Some composers I’ve spoken to are writing the second they get the gig, and like they're looking at the screenplay, or they're just thinking about characters, just seeing what's gonna happen. Others won't do a thing until they see footage. So where are you?

PEMBERTON: Every time I do a film I try and mix it up and do it differently. So some films I get involved really early on, like as soon as the script comes in. Let's say, Steve Jobs, Danny Boyle, I was writing the stuff before they even start shooting. Danny's playing it on set, it’s inspiring him to shoot things differently. And then there are other films where– Let's give you an extreme example; I just did Ferrari with Michael Mann. I scored that entire movie in a week. It was crazy, and they'd finished the film pretty much.

How did you do the score in a week?

PEMBERTON: It's like being a Ferrari driver. It's like, foot on the pedal and just go.

Okay, wait. The movie has to be at least two-hours-and-something.

PEMBERTON: Yeah.

How do you write that much music in a week?

PEMBERTON: Quickly. [Laughs]

No, I’m being really serious.

PEMBERTON: Basically, he– How do I put this? He has a colorful reputation for how he deals with composers, but he's a really fucking amazing director, and so many of his films I absolutely love. So, I couldn't do it, and then they kept asking me, and I was like, “I can't do it, I’m doing other stuff.” Then suddenly, I had a window, but a very small window, and I was like, “Okay, let me have a look.”

I was originally just to come on to just do the racing scenes. He just wanted help. The racing scenes weren't working, and he just wanted to feel better. With Michael, the sound is so focused on sound and visuals and the impact of everything, and one of the big things with this film is the sound of those cars is the score in some ways, and the score must not tramp on that. The sound of those cars is a really important part of the story, so musically, I have to give it energy but create a space for the engines. So I just wrote really high frequency, high strings energy there, and very low stuff, so the engines could become part of the score as well. So I did a whole bunch of those sequences, and he's like, “This is great,” and then he just said, “Just score the rest of the movie.”

So I started writing on a Thursday, and we were recording the following Wednesday with an orchestra. It was really intense, but it meant—without it being like a crap cliché—being like a Ferrari driver of like, you just have to rely on your gut instincts and almost not think about it and just move incredibly quickly. Yeah, it's a pretty extreme experience.

I've never heard of anyone on a big project like that work that fast.

PEMBERTON: Yeah, even I'm like, “It's kind of nuts.”

So I'm assuming Michael then was happy.

PEMBERTON: Michael is really happy. He's a difficult man to please, apparently, with music. But I saw him last week, and he was just like big hugs, and he was like, “The film sounds great.” I mean, I'd say it's a sort of slightly more understated score than I normally do, but again, it's what works for his process and what works for the film.

Sure. I haven't seen the movie, obviously, so what do you think of Adam as Ferrari?

PEMBERTON: Adam's great. I think Penelope Cruz is amazing in it. I mean, for me, the thing that's most exciting in the movie is the racing. The racing sequences are phenomenal. They're just so visceral, and it really throws you into that fucking crazy world of racing where they're just basically sitting on rockets and guiding them somewhere with no seatbelts.

Well, the other thing that people aren't realizing, that maybe they don't know yet, is that it takes place in the ‘50s, and that's a different world.

PEMBERTON: Oh, yeah. I think the thing that's interesting about the film is it really gets you into the madness of what motor racing is. How motor racing started and why motor racing exists is crazy. Around that period, your friends are dying all the time. The film deals with a lot of grief as much as it does racing. The film is a complex drama with some really awesome racing sequences.

Yeah, I want the movie to be awesome. I'm totally rooting for it. And I’m obviously rooting for Heat 2 to happen.

PEMBERTON: Yeah. He pitched me Heat 2. I was like, “I don't know if I can do another one…” and then he pitched me Heat 2, and I’m like, “Fuck, this sounds really good.”

Well, Heat’s a fucking masterpiece. The original is insane.

PEMBERTON: Yeah, I mean, again, the way the music was used in that film has had such a big impact on me as a composer. And that's what I mean about him as director. It's like, you know, people like him, Danny, Ridley, when they've used music in certain ways, it's so powerful because it's different.

100%. So, I'm going to see what I can get out of you, have you started on [Spider-Man: Beyond the Spider-Verse] or no?

PEMBERTON: No one talks about Beyond. There’s a pact at the moment because we're all like, “We don't want to talk about it.”

Yeah. I've said this to (writers) Phil [Lord] and Chris [Miller] and everybody else, I learned after watching Across the Spider-Verse that all the titles are very literal. You know, it's Into the Spider-Verse, it's Across the Spider-Verse, and it's Beyond the Spider-Verse, so I've been asking them, is there any chance of live-action in Beyond the Spider-Verse?

PEMBERTON: Oh, that's above my pay grade.

Yeah, I'm making a joke about it, but they're very literal titles, so what does “beyond” mean?

PEMBERTON: I don't know. It's probably like, it just sounds cool, right? Like, if you look at Alien, Aliens…

Sure. But the first one is Into, the second one is Across, which it is, and then– You're right. It could just be a fun time.

PEMBERTON: Yeah, it's like, are they gonna call it Across the Spider-Verse again?

Sure. Maybe I'm digging deep, but I don't care. I'm holding out hope it's going to be something like that. I love those films, they're incredible, but I would imagine after the success of the first film, did you apply or did you feel any individual pressure because of the success of the first film, or were you sort of like, “I can do anything in this now?”

PEMBERTON: No, everyone in that film felt a huge responsibility after the first film, and sort of anxiety, like, “We’ve got to take the first film and push it even further.” Because I think the first film gave us license to be creative, and we can either sit back and just do more of the same, and people would still love it, or, “Let's see how far we can push this.”

If you look at Terminator and [Terminator 2: Judgement Day], or Alien and Aliens, how both those movies took a concept and just blew it up even wider, I think that's kind of what they're doing with this movie where you've got something where rather than take the easy way out, they took the most extreme way out they could. I'm not gonna lie, Across the Spider-Verse was really, really fucking hard, but everyone was pushing to make something that felt like nothing you'd seen in the cinema before, nothing you'd heard in the cinema before, and I think that's why people have responded. They're so excited about it because that's what people want in the cinema; they want to hear stuff that doesn't sound like scores they've heard before, they want to see things that don't look like things they've seen before. I think we all knew we had a responsibility to, when you have that situation where you can do that and get away with it, and it'd be popular, you've got to take it.

It's so exciting to see how well that film has done and the reaction to it because it really justifies the economics of being groundbreaking. If people start to realize that's what people want, they don't want the AI-driven algorithm telling them to do more the same, they want human-driven stories that are based on the individual, it involves the need to do something new and creative and different.

I'm also going to say, though, that you have a lot of stuff. For example, you have a Spider-Man character. Spider-Man is very popular. You have a great script, you have great innovative animation. You have everything coming together, and it's all working, and that's going to get people to come out. But the truth is, if that screenplay sucks, even with everything else, you know…

PEMBERTON: Every time there’s a great movie, the thing I've really learned about doing movies is when you see a great, great movie, it’s because every single person in that movie did not drop the ball. Let's look at Die Hard; everyone in that movie, from the score by Michael Kamen, the direction, to the acting, to the script, to the production design, everyone's at the top of their game. As soon as one of those things is a bit hokey, it takes you out of it. And when that happens it is very, very special, and I am aware, more now, of how lucky you are to get involved in just one or two of those things in your life.

100%. There are obviously Easter eggs in these Spider-Verse movies that are still being discovered or hidden away because they’re really random. So since the movie's been out now for a little bit, what's an Easter egg or two that you have in there or that you've noticed that people haven't found?

PEMBERTON: I wouldn't necessarily call it Easter eggs, but there were so many references within the score to each other. So the first film and the second film, musically, they all connect. So everything in that film connects to do with melodies, sounds, themes, and the way things adapt. There's really obvious stuff like each character has a sound and a theme, but then there’s things like certain noises representing certain sounds. My favorite thing is that the noise that opens the very first film, this kind of like white noisy—I can't really make the sound of it—that is the sound of the Multiverse. So when Miguel really explains canon event and the Multiverse, that's the sound you hear.

Do you know about the goose? In the first one there’s record scratching, so in this new one I wanted to try and scratch everything we see on screen, so I got the sound department to give me all the noises. So in that sequence, we're scratching the car crash, then we scratch the felt tip pens as he draws, then we scratch the spray cans, the punch sounds in the fight. Then when we get to the goose. You know the bit where he's with the goose and they're fighting? I was like, “We've got to scratch a goose sound,” so we have a record scratch goose. It's one of these things that's in the score, and it's such a ridiculous thing, but a film that allows you to record scratch a goose as part of its soundtrack is something, which for me, that's great at pushing the boundaries.

The thing that I don't think people realize is, and what I give credit to Sony and anyone who was involved in green-lighting for, is the fact that this doesn't happen in Hollywood. These kinds of movies where it's, like, extreme taking a chance with a big IP and letting the artists be artists.

PEMBERTON: I think because it was animated, I think on the first film we definitely didn't feel like we had the same kind of pressure that we did on the second film because the first film was a bit of an under-the-radar, leave-you-alone. For the second one, I definitely felt like there was a lot more expectation for it. The thing about the first film was the first film established, “Let us be creative. If you let us be creative, we'll create something cool.”

100%. My thing, and I said this to Chris and Phil, is that once a studio has a winner like that, something that wins the Oscar, where it makes money, where people just love it, then all of a sudden, that's when the executives start saying, “What else can we do with this?”

PEMBERTON: Yeah. And I think the success of this film has shown that it is smart to let the creatives go crazy because if you can keep that energy in a film– I hope we can keep that going because it is why people are connecting with the film because they're connecting for the same reasons we connect with it when we make it.

Sure. I'm wondering what's going to happen after Beyond. Obviously, the studio is not going to do anything until Beyond comes out, and then the question becomes, what does the studio want to do?

PEMBERTON: Yeah, I know what you mean because, first of all, to work at that level for more than three films, I don't think it's possible because it is so extreme. The amount of creative juice we've all given to the film is crazy. You remember, you watched that movie, and think of the level of intensity and creativity on the screen, and then imagine how much is not even on the screen, the ideas that got thrown out, things that we chucked, things we redid millions of times. There was so much of that.

That's why I'm very thankful that they were made. And will Chris and Phil want to continue making these kinds of movies, or will they be like, “We're taking a 10-year break?”

PEMBERTON: [Laughs] Right now, I think everyone wants to be like, “We're taking a 10-year break,” but we've got these other movies, so we're not.

Completely.

PEMBERTON: Also, I think a bit of wait between films is exciting. I think everyone's so used to things just being force-fed down them. You look at Star Wars, everyone's got bored of Star Wars because Star Wars films are coming out…

Well, they also weren't all that.

PEMBERTON: Yeah, but let's look at Bond, which also the films, they're not all that, but there's such a big wait between them that when they come you're like, “Oh my god. The new James Bond film.” It's an exciting moment.

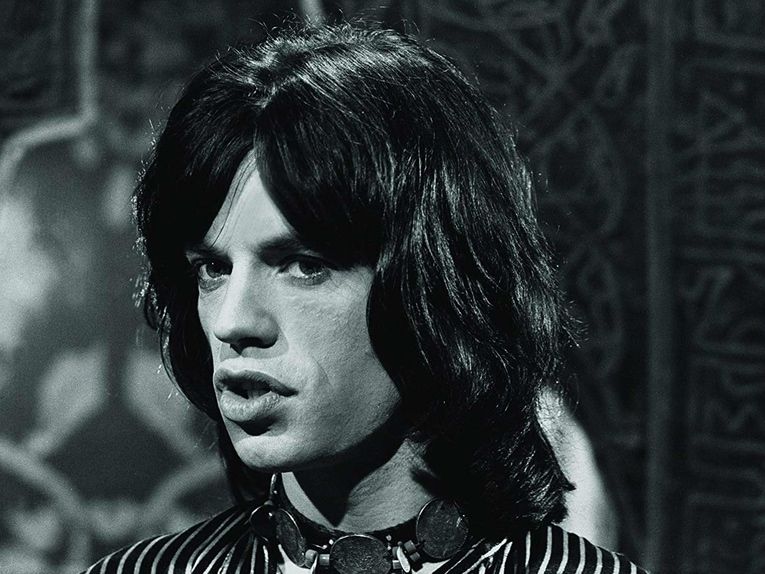

I'm a fan of Slow Horses. I really enjoy that show, and you got to work with Mick Jagger on the theme song, which is crazy. So what has it been like working on that show because it's very well done?

PEMBERTON: Working with Mick was insane. First of all, just from a human level, he's just really lovely, down-to-earth. He just gave me his number and just says, “Just call me or text me.” We wrote that song remotely over text messages and voicemails and phone calls and chatting. But having these long chats with Mick Jagger, and he really cares. “Oh, let me do the vocals,” and I’d say, “I love this bit. Let's change that. Let's change this bit. I’ve got it, it’s fine.” “No, no, no we’ll redo it then.” And also, just working with his voice is amazing because you get this recording of his voice, and it's such an iconic sound, that voice is such an iconic part of the 20th century. It's like having a Picasso painting or a Van Gogh or something, where it's got such an individuality to it. You're like, “Wow, I get to do something with this.” That's been one of the high points of the last two years of just doing that song with him. And also, he's just been really great to deal with, and he just nailed those lyrics really quick. I mean, he nailed that so fast. I was like, “Oh my god, you just summed up the whole show in like 40 seconds,” you know, that opening sequence. It's been brilliant.

Yeah, I don't know what I would do if I had his number. I have the phone number of a whole bunch of people that are cool, and I don't actually use it.

PEMBERTON: No, the Mick Jagger thing is– He came down to a Spider-Man session. He was in Abbey Road doing some Stone stuff and so he came into the Spider-Verse session when we were recording Spider-Verse, and we played him some stuff, and he was like, “Yeah, this is great.” That was quite a cool moment. I had to cut off a brass session very abruptly. “You're all on break.” “Why are we on break?” “I'll tell you in a minute. I've gotta go.” Then the break’s kind of getting to the end, they're all back in the room, and so I walk into the room, and I'm like, “Ladies and gentlemen, so Mick Jagger!”

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse is in theaters now. Check out Collider's interview with writers Phil Lord and Chris Miller below or you can read the full conversation here.