Daniel Pratt (eccentric)

"General" Daniel Pratt, Jr. (April 11, 1809, in Prattville, Chelsea, Massachusetts – June 21, 1887, in Boston) was an American itinerant speaker, author, performance artist, eccentric, and poet.

Life and work[edit]

Pratt trained as a carpenter but abandoned this craft and wandered about the country doing freelance lecturing. He claimed to have walked over 200,000 miles, from Maine to the Dakotas, visiting 27 states and 16 Indian tribes.[1] He was widely known as the "Great American Traveler," which was how he referred to himself with his characteristic disdain for modesty. His visits to American colleges came to be regarded by the students almost as a regular feature of campus life.[2]

He was often an appreciated and honored guest and speaker, though usually met with tongue-in-cheek praise. At times, though, his welcome came pre-worn-out, as when he rushed in on Leonard Bacon as he was entertaining guests at home, shook his hand and announced expectantly, "I, Sir, am no less a man than Daniel Pratt – Daniel Pratt, Sir, the great American traveler!" Dr. Bacon, unimpressed, replied, "All right – Travel!"[3]

Pratt was a prolific and generous generator of ideas, but in spite of this was heard to complain that "it was utterly impossible for him to talk fast enough to get out his ideas, so rapidly did they grow in his fertile brain."[4]

Lectures[edit]

Pratt lectured widely, not only on university campuses, but in town halls, churches, and wherever he could find an audience. He would attend meetings of many varieties, from religious ceremonies to city government meetings to women's suffrage conventions, with the hopes of being able to address the assembly.

One newspaper announcement from 1853 invited readers to "a LECTURE on The Laws of Mind and Matter, at the lecture-room of Hope Chapel… The Universe is a globe of laws, and the whole animate creation exists and is governed by them. There is an infinite power above them all, and manifested in different bodies, subject to the will of the Law giver of Nature. Ladies, free; gentlemen, 25 cents."[5] Another, from 1864, advertised "the Hon. DANIEL PRATT, the Great American Traveler and editor of the famous Gridiron, and author of a work entitled the 'Beacon Light,' and candidate for the Presidency, on the power of Master Leading Mind and the War Equilibrium, interspersed with poetry and anecdotes, at the Apollo Rooms… Tickets admitting a gentleman and ladies, fifty cents. Single tickets twenty-five cents, to be had at the door on the evening of the oration."

Pratt would appear in "threadbare coat,"[6] "battered tall hat, seedy attire, and imperturbable solemnity of countenance"[7] and deliver his talk, "characterized by a dazzling faculty for word-creation, a complete mastery of the non-sequitur, and a lambent humor."[8] Afterwards, if there had been no admission price, he'd pass the hat.

One author remembers seeing Pratt on campus:

Toward the close of a September day in the year 1864, a crowd of students was collected on the Bowdoin campus near the Thorndike oak. Each class was not only represented, but present almost in its entirety; still, as the college at that time bore upon its rolls only about a hundred names, the reader is not to imagine the assembly as one of remarkable proportions. The several classes, without being grouped as separate bodies, were in a measure distinct, as if their members were drawn together by community of sentiment or interest. The center, of the throng was composed mainly of Sophomores who, to the melody of tin horns, devil's fiddles and watchmen's rattles, from time to time added vocal effects scarcely less loud and discordant. Next to them stood the open-eyed Freshmen, eagerly appreciative of the novelty of the scene; while most of the upper-class men were ranged along the outer edge or a little apart, and were endeavoring to preserve looks and attitudes of aloofness and indifference. The object of attraction appeared to be a tall, spare man who was standing upon a rude plank-and-barrel rostrum, and, whenever the uproar would permit, launching his remarks in a violent manner at the bystanders. He was apparently some sixty years of age. His head was uncovered, showing his hair thin and streaked with gray. His face was smooth except for a stubbly two days' growth of beard, and was wrinkled and browned by exposure to the weather. Beside him upon the platform rested a dilapidated silk hat which, as well as his suit of rusty black, looked as if it might have been discarded some years before by its former owner. They were not, however, incongruous with the rest of his attire, since both his dickey above and his shirt below his black stock bore the same signs of poverty and neglect.

...I was late in my arrival at the scene on the campus and in consequence heard only the conclusion of the speaker's harangue.

"Gentlemen," he was saying as I approached, "what do we mean when we say that a man is 'some pumpkins'? We mean that he is full of ideas just as a pumpkin is full of seeds. What do we mean when we say that he is a 'brick'? Why, a brick is part of a building. Let us now consider the attraction of gravitation, that mysterious force which binds together atoms and worlds, princes and parallelograms, cones, pyramids and the Sphinx. A traveler is lost on a Western prairie. He has wandered all day, far from home and with nothing to eat. Night comes on. The wolves begin to howl in the darkness. At last he reaches a log cabin, almost in ruins. No matter, it will afford him shelter for the night. Scarcely has he entered and composed himself to rest when a violent storm arises. Thunders roar. Lightnings flash. The snow heaps against the door. It grows bitterly cold. What shall he do? He can't stay there and freeze to death. Let me illustrate. Two darkies, walking down Broadway, saw a quarter of a dollar on the sidewalk. One of the colored gentlemen said to his companion, 'Sambo, don't you freeze to dat quarter. I seed it first.' That is just the idea. He can't stay there and freeze. His soul—but what do we know about the soul? Is it homogeneous or heterogeneous? Who can tell? Who except me, Daniel Pratt, the Great American Traveler, and soon to be President of the United States? Why not? Was not imperial Rome once saved by the cackling of a goose?"

The applause, by which the orator had been frequently interrupted, at this point became so vociferous and long continued that it was impossible for him to proceed. He at last desisted from his attempts to do so and descended from the platform. He had been speaking more than three-quarters of an hour, and the students, tired of listening to his rambling and incoherent remarks, had adopted the most efficacious method of bringing his address to its conclusion.[9]

The students then nominated Pratt for the US presidency, and passed the hat to buy him a new pair of shoes and a meal.

One journalist recalled an occasion on which Pratt lost his notes but did not lose his composure:

His remarks were written in two-inch-caliber chirography on the reverse of a roll of wall-paper, which the orator unwrapped as he proceeded until he was almost lost to view in the billows of white. Once an unprincipled sophomore crept up behind him and touched a lighted match to the manuscript. For a moment the perpetual candidate resembled a plate in Fox's "Book of Martyrs"; but without the slightest change of expression he trampled out the flaming Vocabulary Laboratory and went on calmly…[7]

Only partial transcripts of Pratt's lectures have been found, but many times they were referred to by title or subject in the popular press of the time. The Brooklyn Eagle considered "Equilibrium" to be Pratt's signature lecture topic. George H. Genzmer noted topics like "The Four Kingdoms," "The Harmony of the Human Mind," "The Solar System," and "The Vocabulaboratory of the World's History."[8]

A journalist paraphrased one of Pratt's lectures thus:

Gentlemen, I have come up through great tribulation. I am in possession of a vast profundity of knowledge on the sciences of the universe, that when written out and published will be worth thousands of millions of dollars to our nation. God has favored me physically and mentally from my birth. The time has come for the industrial and educational sciences to be represented at the head of the American Government. And I have been speaking over twenty-five years on different subjects, almost without pay. I have spoken thousands of times without one cent or a crumb of bread or a place to lay my head. I have also spoken over a hundred times since last June from New York City to Toledo, Ohio, and all the presidents of the railroads have paid me was one dollar and a half. Man is the architect of his own weal. My circular entitled 'The Pratt Intellectual Zenith' is progressing.[7]

Because of his high self-regard and his eccentric subject matter and delivery, Pratt was often subjected to mockery, sometimes of a cruel nature. On one occasion during the U.S. Civil War, he was lecturing to a regiment of Union army troops, who slipped forged correspondence from Confederate president Jefferson Davis in his pockets. Pratt was arrested on charge of being a spy, sentenced to death in a mock trial, blindfolded, and "shot" by a dozen riflemen using blank cartridges.[10]

Debates[edit]

Pratt periodically challenged the intellects of his day to debates. He once challenged William Lloyd Garrison and Wendell Phillips to a debate on "the virtues of the Abolition Party and Political Platform."[11] On another occasion he challenged Henry Ward Beecher, Edwin H. Chapin and Andrew Jackson Davis to a debate on "which is the smartest man in all points of view."[12] In April 1854, he shared the stage with an all-star cast of eccentrics, including Father Lamson and John S. Orr ("The Angel Gabriel") before an audience of thousands in Boston.[13]

Writing[edit]

Pratt wrote a periodical, the Gridiron, as a tribune for his considered opinions, and also published broadsides and a book or two. In 1852, he announced the publication of "a work… on the glories and wonders of the universe, in map form."[14] In 1882 The Tech — MIT's student newspaper – gave this description of Pratt's work:

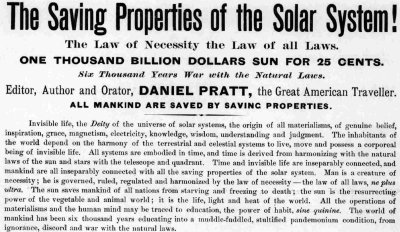

We take pleasure in giving publicity to the next great work of Gen. Daniel Pratt, the travelling encyclopedia and universal genius, the library of facts, the original oratorical author, the great favorite of the students of all the colleges, the greatest pedestrian in the world; been talked of for the mayoralty, the governor, member of Congress, and the President of the United States for the last twenty years; the general of generalities, the harmonizer of the laws of the solar system, the only value of knowledge and wealth of the universe of worlds, non terra sed cosmos. Following is a synopsis of the contents of the work: Mark the March of Intellectual Developments of Mind. — The Great American Travelling Luminary. — The Perpetual Repeating of Immutable Images. — The Medium Criterion of all Professions of Men. — One Thousand Billion Dollars Address. — The Sun the Saver of Savers of All the Properties of Life. — The Vocabulary Laboratory of the Universe of Ideas. — The City of Chelsea, Mass., the Medium of the Ingenuity of the World. — The Law of Necessity the Law of All Laws. — The Solar Systems are not One Thousand Millionth Part Developed; a Vast Field for the Observation, Investigation, and Reflection of the Students of all the Colleges in the World. By the Editor, Author, and Orator Daniel Pratt, the Great American Traveller, Boston.[15]

Political campaigns[edit]

Pratt witnessed the inauguration of five presidents, and is said to have believed that he himself had been elected president but defrauded of the office.[1] He was a frequent presidential candidate. One of his abbreviated campaign platforms was printed as a letter-to-the-editor in 1855:

Fellow Citizens, As I am a Member of the Press, Editor, Author and Publisher and Candidate for the next President of the United States of America in 56, It is due the People, that I give them some idea, of my Political Platform, I am for the Constitution right or wrong, I know no East, west, north or South, but my country, the People, the whole, People. If it had not been for Emigration, America would be people by the Indians and the wild beasts, Emigrants has built up and inriched America, I am in favor of holding up our identity as an Nation, to all Nations in the world, to Nationalize all Nations who come under the stars and stripes of the American Flag. It will take eight years to right up, and set the broken limbs of the People who compose our Nation. I want a Lady, of talent, and a little money, who never was Married to address me, by Letter at the New York Post office, in good faith, all confidential. I challenge in good faith the Hon. George Law, to meet me in some good Hall in this City, to give the People an opportunity of Judging who is the most available man for the President of the U.S.A.[16]

Pratt occasionally came into conflict with another Boston eccentric with presidential aspirations, George Washington Mellen. At one point, Mellen accused Pratt of accepting £250,000 from the Pope in preparations for raising a large army of insurgents to take on the United States government. Pratt responded to this slander by accusing Mellen with high treason.[17]

Pratt spoke at the 22nd Anniversary of the founding of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1856, as the New York Times reported:

Daniel Pratt, Esq.… Let him that is sent of God preach. Listen, for I am not going to make a speech. In this great country the Government was founded by the people; it was founded by the people for the people; and I am for the laboring classes. I don't think it is right for man to enslave his fellow-man. It is to God and this great and glorious country's institutions that I owe my present high, exalted position. [Applause.] It is to it that I owe my many hair-breadth escapes, during my great travels and perils by land and sea and mountain. [Great applause.]

A Gentleman on the Platform — I submit, Mr. President, Is the gentleman in order?

The President — I trust the audience will bear with this particular case. I think it will not last long. (Turning to Mr. Pratt) Please, Sir, to be as short as possible.

Mr. Daniel Pratt, (continuing) — I'll wind up with a poem. [Enthusiastic applause] But, perhaps, as my name has not been announced, some of you may not know who I am, and so I'd better tell you, so that you may know. I am Daniel Pratt, Esq., the great American traveler and independent candidate for the Presidency – and I won't flinch a hair, [Enthusiastic applause and a few hisses.] Now I'll read the poem, It is

A SENTIMENTAL POEM.

May the load of oppression be banished afar,

And poverty never be heard on the lea;

May peace and contentment be thy polar star,

And justice and equity grow like a tree.

May learning and commerce forever increase,

And science and genius in every degree;

May the loud cries of war be changed into peace,

And each party spirit join hands and agree.

Ne'er again may the prisoner be heard from chis cell,

To mourn and complain for the crime he has done,

Make the Bible the compas by which thou dost steer,

Then safely thou'lt ride o'er the rough dashing wave

[18]

In 1864, Pratt went to see President Lincoln at the White House, and "left a roll of printed and written paper" for the president to peruse. The president, busy with the duties of his office, did not understand what he had received and returned the papers to Pratt via a White House staffer, with instructions to receive no further papers. Pratt felt this insult sorely, as he, in spite of his regular campaigning to himself fill Lincoln's office, considered himself one of the president's most hard-working supporters. The newspapers from Washington reported the encounter in the most unflattering terms, saying that "a crazy man had got into the White House, had harrangued the President, and had endeavored to convince that functionary that he (the crazy man) had been elected President in 1856.… [Guards] seized the intruder and bore him from the sight of the offended Executive."[19]

In 1867, the students of Trinity College in Connecticut, in response to one of Pratt's speeches (which the papers described as "a highly polished, scholarly affair, abounding in flowers of rhetoric and striking similes"), unanimously nominated Pratt to run for the United States presidency. They nominated a favorite African-American janitor, "Professor" James Williams, as his running mate.[20]

"Persistency finds its practical incarnation in the person of Pratt," the Brooklyn Eagle wrote, in an editorial endorsement of sorts of Pratt's 1867 campaign. "[H]e has been nominated by over twenty colleges, and if he can only get the Electoral College, of which there is little doubt, he will be all right."[21] Pratt eventually abandoned this campaign so as not to hurt the candidacy of Ulysses S. Grant.[22]

Honors[edit]

The June 1870 Hamilton Literary Magazine reported:

Among the many trophies in the State Police Headquarters, in Boston, is a pewter pitcher, seized at a saloon on Causeway street, which is inscribed: "Presented to Daniel Pratt, Jr., Chelsea, the Great American Traveller, Orator and Patriot; the Friend of Humanity, the Ladies, and a Free Country generally; the Defender of the Rich and Juicy, wherever found, and however bound. Testimonials from Citizens and Admirers, at Grove Hall, Dorchester, August 15, 1845.[23]

George H. Genzmer wrote that Pratt was "the most widely known and affectionately remembered man of his class, the subject of innumerable anecdotes, reminiscences, rhymes, and allusions. This fame he owed in large measure to his devotion to the New England colleges, where … by the students he was received with an enthusiasm that quickly permeated the community and mounted to a height of ebullient demonstration scarcely distinguishable from a riot.… An impressive but quite unofficial convocation at Dartmouth College conferred on him the degree of C.O.D."[8]

A poem in Pratt's honor has been preserved, though its context does not indicate who composed it and hints that it may have been Pratt himself:[24]

Oh, where is the man so lean and fat[a]

Who has not heard of Daniel Pratt,

Who gathers his wings and flies away

To parts of earth were the light of day

Shines but a little or not at all

In the course of the awful waterfall?

I ask you, friends, what muddy minds

Have never conceived, unfurled to the winds

That glorious banner that springs like a cat

Into the air for Daniel Pratt.

There never was nor ever will be

Such a mighty man to stand like thee,

I say, most magnificent Daniel Pratt,

Above the throne where Plato sat!

Quotations[edit]

My Parents said to me one day about 10 years ago, you cannot be a Henry Clay or a Daniel Webster, for you have not had a college education – said I, I can be a Daniel Pratt, Jr., and that is all I want to be.[25]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ other sources say this line should read "Where is the man so rich and fat"

See also[edit]

- Pratt, Walter M. (1930). Seven generations: a story of Prattville and Chelsea.

- Wright, Richardson (1927). Hawkers & Walkers in Early America.

References[edit]

- ^ a b "End of a Wanderer's Life: 'The Great American Traveler' Makes His Last Trip". New York Times. June 22, 1887. p. 5.

- ^ Wilson JG, Fiske J, eds. (1900). "Pratt, Daniel, vagrant". Appleton's Cyclopædia of American Biography. Vol. V (Pickering-Sumter) (Revised ed.). New York: D. Appleton and Company. p. 101. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ^ "Some Hit And Miss Chat". New York Times. September 7, 1885. p. 2.

- ^ "Grand Demonstration: Arrival in Brooklyn of the Celebrated American Traveler, Gen. Daniel Pratt, Jr. — Eloquent Discourses of Prof. Ambrose and the General". Brooklyn Eagle. October 11, 1859.

- ^ "Special Notices". New York Daily Times. New York, N.Y. February 3, 1853. p. 1.

- ^ "Dan Pratt Dies: The Great American Traveler's Career Closed: His Earthly Wanderings Ended by Paralysis in the Boston City Hospital — The Old Man's Eccentricities". Brooklyn Eagle. June 21, 1887. p. 6.

- ^ a b c Mitchell, Edward P. (1924). Memoirs of an editor: fifty years of American journalism. New York: C. Scribner's Sons. pp. 70–71.

- ^ a b c Genzmer, G.H. (1935). "Daniel Pratt". In Malone, Dumas (ed.). Dictionary of American Biography. Vol. XV. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 170–171.

- ^ Webster, H.S. (1901). "In the President's Room". In Minot, J.C.; Snow, D.F. (eds.). Tales of Bowdoin. pp. 127–136.

- ^ "(untitled)". Chelsea Telegraph and Pioneer. June 7, 1862. pg. 2, col. 6.

- ^ Monti, Daniel J. (1999). The American City. p. 132.

- ^ "Personal". New York Times. May 2, 1860. pg. 1, col. 2.

- ^ "Birds of a Feather". New York Times. April 12, 1854. pg. 3, col. 4.

- ^ "City News & Gossip". Brooklyn Eagle. April 2, 1852. p. 3.

- ^ "The Title of a Great Work". The Tech. 1 (9): 102. March 8, 1882.

- ^ Pratt, Daniel (December 5, 1855). "Letter from Daniel Pratt, of Boston – Challenge to George Law". New York Daily Times. p. 4.

- ^ "Presidential". New York Daily Times. July 20, 1855. p. 4.

- ^ "The Anniversaries". New York Daily Times. May 9, 1856. p. 7.

- ^ "Pratt Versus Lincoln: The Difficulty between Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Daniel Pratt, Jr.: Pratt's Account of the Affair". Brooklyn Eagle. March 31, 1864. p. 2.

- ^ Proctor, C.H. (1873). The life of James Williams, better known as Professor Jim, for half a century janitor of Trinity College.

- ^ "The Next Presidency – The Campaign of 1867 – Probable Chances of Daniel Pratt, the Great American Traveler, and Author of the Great Cosmographer". Brooklyn Eagle. June 21, 1867.

- ^ Mitchell, Edward P. (1924). Memoirs of an editor: fifty years of American journalism. New York: C. Scribner's Sons. p. 71.

- "Topics of To-Day". Brooklyn Eagle. November 20, 1868.

- ^ "Editor's Table". Hamilton Literary Magazine: 357. June 1870.

- ^ Grant, Robert (1897). "Harvard College in the Seventies". Scribner's Magazine. XXI (5): 559.

- ^ Pratt, Daniel in the Gridiron No. 6, which was in turn quoted in the Boston Post (date unknown), which in turn was quoted in "Pratt v. Bachanan" New York Daily Times 25 June 1856, p.4

External links[edit]

- The saving properties of the solar system! The law of necessity the law of all laws. One thousand billion dollars sun for 25 cents. Six thousand years war with the natural laws. — one of Pratt's broadsides from Boston in 1882, from the Library of Congress's Printed Ephemera collection