Since it came out five months ago, a debut work by an 87-year-old has become a publishing phenomenon. Lady in Waiting: My Extraordinary Life in the Shadow of the Crown by Anne Glenconner has sold more than 200,000 copies in the UK and retains a tenacious hold on the bestseller lists. Written by the former lady-in-waiting to Princess Margaret, its broad appeal might seem surprising, not least because Margaret was hardly the most popular royal. But Lady Glenconner’s book has two things going for it: the first is that it is not what it seems; it is definitely not “a lavender sort of scented memoir”, as Glenconner put it when she appeared on The Graham Norton Show last November. And its other great strength is Glenconner herself.

“Are you really tired after your journey? Did you find a taxi when you got off the train?” she asks when I arrive at her home on the Norfolk coast. She has the accent of the Queen – “really” becomes “rill-eh”, “off” is “orff” – and is dressed like her too, in a blouse, cardigan, pleated knee length skirt, tights and loafers. It is easy to picture her striding around the world, making small talk with Imelda Marcos, which is what she used to do with Princess Margaret. I lean in to kiss her, but then ask if she’s refraining because of the coronavirus. Glenconner looks at me as if I’ve left my marbles on the train: “I’ve been through the second world war and lived with someone with Aids at the beginning [of the Aids crisis]. I’m not scared of a little virus, you know,” she says. She turns on her heel and marches down her long hallway, and I have to scoot to keep up with her.

Glenconner was born Anne Coke (pronounced Cook), the daughter of an earl. “So I married down somewhat,” she says with a satisfied smile, as her husband, Colin Tennant, was merely the Baron Glenconner. In her book, Glenconner describes her current home as “a cottage” but these things are relative: compared to the nearby Holkham Hall where she grew up, and Glen, the enormous estate in Scotland belonging to her late husband’s family, I guess it is a cottage. To me, it looks like a sizable house, with a warren of rooms filled with family portraits and vintage toys that are now kept for her grandchildren and great-grandchildren. She takes me to the pretty sitting room, where we sit on either side of the fire. “When Princess Margaret would visit the two of us would sit just like this,” she says. “One time she came with her kettle and said: ‘I’m going to be independent, Anne, all you need to do is give me some milk.’ I was a bit doubtful and I was right because suddenly one morning it was ‘Anne! Anne!’ ‘Yes, ma’am, what is it?’ ‘I think the kettle’s broken!’ Of course, she hadn’t turned it on. But she did want to help …” Prince Charles, another “proper friend”, stops by often: “And people are really fond of him now, you know. All that talking to plants and his green things, it’s all come true. People don’t laugh at it.”

I tell her that even the most republican of my friends love the book.

“You know, I’ve never written anything in my life at all, and I thought: ‘Well, people like me might buy it.’ But it’s gone way beyond that. I certainly didn’t think the Guardian would be interested in my book. I know you’re a very leftwing newspaper and somebody like me is not quite your cup of tea, so that’s encouraging.” On a table nearby, a Daily Telegraph is tucked discreetly under a cushion.

Glenconner composed the book in this room, dictating her life story into a recorder. “Somebody said: ‘Do you get writer’s block?’ I said: ‘No, writer’s diarrhoea!’ I just talked and talked,” she says. Glenconner’s distinctive voice has a no-nonsense briskness to it, undercut with a wry but warm sense of humour. She manages to laugh at things others might find less amusing: the patriarchal aristocratic system that meant she couldn’t inherit her family home (“I tried awfully hard to be a boy, even weighing 11lb at birth, but I was a girl and there was nothing to be done about it”); her husband taking her to a “perfectly disgusting” live sex show during their honeymoon; even her son Henry’s funeral when he died from Aids – “I couldn’t help a tiny smile because, as is Buddhist custom, his coffin was covered with pineapples and other tropical fruit, so it looked like a giant fruit salad as it came into the crematorium.”

“It’s no fun for anyone if you’re sitting around being a misery. I’m no snowflake, probably a battle-axe. I was brought up by my mother to get on with things,” she says. Her family crest is an ostrich swallowing a horseshoe, signifying the family’s ability to digest anything.

Glenconner’s family has a long relationship with the royal family: her paternal grandmother was Edward VIII’s mistress and her father was equerry to George VI. Glenconner was Princess Margaret’s devoted lady-in-waiting for more than 30 years, and this is what spurred her into writing her book, as she was horrified by a recent biography about the princess, which she describes as “that horrible book, we won’t mention the name of the somebody who wrote it. I don’t know why people want to rot her like that.” When I ask if she means Craig Brown’s book, Ma’am Darling, she gives a pained, terse nod.

Determined to rectify the common perception of the princess as spoilt and spiteful, Glenconner writes about Margaret’s various kindnesses to her. They were, she says, real friends, even if one called the other “Ma’am” and the other didn’t. “I would have felt quite uncomfortable calling her anything else. But she was so funny, that’s what people don’t get,” she says. After the princess died, the Queen thanked Glenconner for providing her sister with many of the happiest moments in her life.

I’d been warned beforehand not to ask about Meghan Markle so I ask instead if, having spent so much time with Margaret, she has extra empathy for the other spares, Princes Andrew and Harry. But Glenconner knows what I’m up to: “You’re edging closer to asking me about Meghan Markle,” she tuts. “I’m going to put another log on the fire before I answer that!”

Markle’s mistake, she says, was to not understand that all the royals, even the spares, work hard: “I think she thought she could drive around in a golden coach. But it’s actually quite boring. Princess Margaret did so much charity work, and without any photographers, unlike the Princess of Wales.” (Glenconner is a staunch royalist, but her sympathies are with the more traditional branches of the family; even Princes William and Harry, she says, “go on about their mother the whole time. I think it’s a bit much.”)

Coverage of Glenconner’s book has focused on the royals, but it’s the descriptions of her own life that gripped me. First, her marriage to Colin, who had frequent mental breakdowns and was a bully; when Glenconner asked him why he screamed at people so often, he replied: “I like making them squirm.” He insisted on telling her about his holidays with his many girlfriends (“I said, ‘Can we talk about something else?’”), but Glenconner got her own back, and makes one fleeting reference in her book to having a “dear friend”. This is the one subject she won’t be drawn on: “I’ll tell you absolutely nothing at all, except that he made my life possible. We had lunch once a week and the occasional weekend for nearly 40 years, and that’s all I’ll say.”

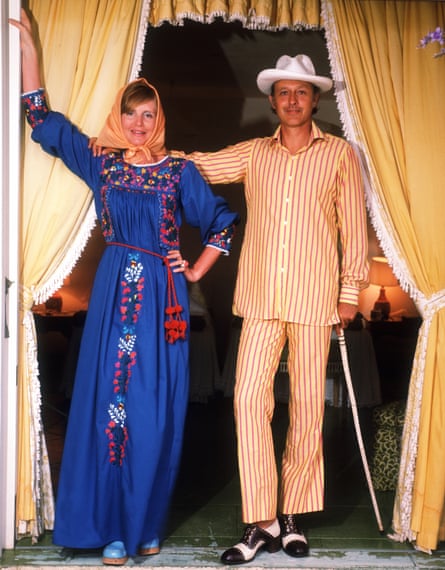

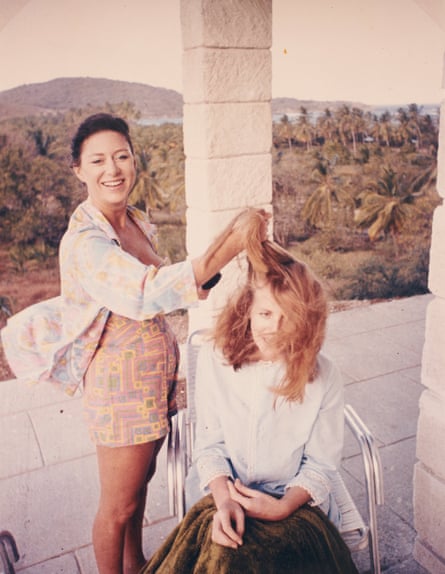

Despite everything, Glenconner painstakingly emphasises her husband’s good qualities in the book, such as his sense of fun and imagination – partly, she says, for the sake of their children, but also because it was true. He turned Mustique from unpromising scrubland into a celebrity pleasure island, where Mick Jagger would lead singalongs in a beach bar. Colin’s parties were legendary for their loucheness, such as the Golden Ball, which was photographed by Robert Mapplethorpe, when Bianca Jagger was carried in by a troupe of boys painted entirely in gold and wearing only “a coconut strategically placed below”. The celebrities revelled in the privacy from the media: on one holiday, Glenconner delicately pointed out to Princess Margaret that her bathing suit was transparent. “‘Oh Anne,’ she said, somewhat exasperated. ‘I don’t care. If [people] want to look, they can look.’ And that was that.” Colin died in 2010 but, Glenconner says, he would be “absolutely delighted” that Mustique is still causing scandals, with questions over who paid for Boris Johnson’s recent holiday there.

The couple had five children: Charlie, Henry, Christopher and twins May and Amy. Glenconner loved being a mother, but, despite not having been entirely happy with aspects of her childhood – absent parents, nannies, boarding school – she repeated it with her own children, leaving them behind as she helped her husband in Mustique. “It’s just what you did, what all our friends did, the shooting parties all winter we went off to – we didn’t think. I didn’t even want them to go to boarding school …” she trails off.

The three youngest children had the same nanny throughout their childhood, but the two eldest, Charlie and Henry, had many different ones, their father sacking their favourites on a whim. By the age of eight Charlie had severe OCD. As a teenager, he got into drugs. Henry married and had a son, but in the late 80s he came out as gay and within 18 months he had Aids, at a time when the diagnosis turned you into a pariah. “I would take Henry to A&E, and it was full when we arrived and within half an hour everybody had left and I was alone with him. He was so ill that we would sit on the floor, with his head in my lap. That was quite hard to write about.”

Meanwhile her youngest son, Christopher, suffered a catastrophic head injury while on a gap year in Belize. He was in a coma and a doctor told Glenconner that she should forget about him. Instead, she nursed him and when he woke up four months later she took him home and cared for him for the next five years. He was left with life-changing injuries, but he has married twice and has two children.

After Henry died and Christopher recovered, Charlie also seemed to be recovering from his addictions. But it was too late: he died from hepatitis, and Glenconner buried her second child. “Often people don’t talk to me about the children, maybe because they’re interested in the other things. But I like talking about them, and perhaps the book has given me a way to do so,” she says.

Her book’s success has thrilled her: “Aren’t I lucky?” She is planning a trip to New York, where Tina Brown will throw a party for the US launch. She is also working on her first novel, Murder in Mustique: “I’m the new Miss Marple!” she says delightedly.

Glenconner talks me through the family photos that surround us: Charlie as a handsome teenager, Henry’s son and his children, one of the twins getting married. A photo of Glenconner holding Charlie and Henry as babies is so bittersweet I can hardly look at it. “Oh I know,” she says when she sees me wince. As I’m about to leave, she touches my elbow gently. “I’m glad you asked me about the children, it was kind of you,” she says. “Because the book really is about them, you know.”