A Historical Overview of Coptic Contribution in Missio Dei[1]

Riad Ghobrial

Riad Ghobrial was born and raised in Egypt. He earned a BSc in Civil Engineering from Cairo University. For many years he has served as a missionary with the Coptic Orthodox Church in Kenya, Tanzania, Nigeria, Congo, and Bolivia. He is the founder and director of Mission of Saint Mark for Evangelism, which aims to reach out to the marginalized villages in Egypt. He is the author of The Journey I and II, a discipleship program for Arabic-speaking Christians (ASFCS, 2021, 2023), Look at Me and Have Mercy (Arabic), a study that examines the Psalms as the cry of the poor (ASFCS, 2022), and headed the team that translated the Coptic Psalmody from Coptic and Arabic to Swahili (2016). Riad is currently working on his PhD at the Oxford Centre for Mission Studies (UK) in the area of Sacramental Theology of the Poor.

Mission Round Table 19:1 (Jan-Apr 2024): 4-11

To read articles in this edition, visit this post on Mission Round Table 19:1.

Introduction

God does not leave himself without witness (Acts 14:17). This is globally true, particularly in the Egyptian lands. Since the first century AD, Christianity has been alive and fruitful among the Egyptians in various ways. And during various ages, Egyptian voices have gone beyond the borders of their country to reach out toward the ends of the world (Ps 19:4). Known now as the Coptic Orthodox Church,[2] the Egyptian church, under diverse, and mostly harsh, circumstances, has contributed faithfully to embodying and spreading God’s salvific message. Since there is a place for recording the unique contributions each church, according to its gifts and personality,[3] has brought to God’s universal mission, in this article, I go on a brief journey to explore the different forms of witness expressed by one of the most ancient and yet surviving churches, the Coptic Church.[4] By looking at the Coptic history of witnessing, this paper seeks to help us identify and reflect on the distinct ways by which a church can give witness to the gospel, and hopefuly bring innovative and inspiring changes for other churches.

Throughout history, Christian mission around the globe has experienced significant waves of change in forms, approaches, and practices.[5] The same is true when examining the Coptic mission, which had its particular paradigm shifts throughout the twenty centuries of Christianity. To help study the history of Coptic witnessing, I divide it into three main eras: (1) The first six centuries, (2) the seventh to the nineteenth century, and (3) the twentieth century to today. During these eras, significant socioeconomic and political changes took place that considerably influenced the witness of the Coptic Church.

First six centuries

Egyptians are deeply religious. As noted by Herodotus: they “are religious to excess, far beyond any other race of men.”[6] Their religious convictions prepared them, in the fullness of time, to receive the message of salvation and embrace it. Furthermore, some extra-biblical accounts see the coming of the child Jesus with Joseph and Mary to Egypt during their flight from Herod’s order to kill the children of Bethlehem (Matt 2:13-15) as mystically paving the way for the gospel to take root and bear fruit among the Egyptians.[7] It is thus not surprising to find indications of Egyptians who believed in Christ from New Testament times. Egyptians were among those who heard the disciples’ testimonies on the day of Pentecost (Acts 2:10), and Apollos, the prominent teacher of Scripture, was a native of Alexandria, Egypt (Acts 18:24).[8]

Saint Mark

Historically, it is nearly impossible to determine how and when Christianity arrived in Egypt. Nevertheless, the third- to fourth-century historian, Eusebius of Caesarea, asserts that John, surnamed Mark, the writer of the Gospel of Mark and the fellow worker of Peter and Paul,[9] was the first apostolic figure to evangelise the lands of Egypt beginning with Alexandria. He is thus considered the founder of Christianity in Africa.[10] Since then, tradition has held this foundational story for the Egyptian church.

The story maintains that Mark was a Jew from Cyrene, a city in Pentapolis of North Africa (modern-day Libya). Due to local disputes, the young Mark with his family had to move to Palestine where he got to know Jesus and his disciples.[11] Some traditions include Mark among the seventy apostles sent by Jesus. According to the History of the Patriarchs of Alexandria (eleventh century), after the ascension of our Lord Jesus Christ into heaven, as the apostles were preaching the gospel to whomever the Holy Spirit guided them, an angel appeared to Peter in a dream and asked him to preach in two cities—Alexandria and Rome—where there was a famine, not of bread and water, but from “ignorance of the word of God.”[12] After this angelic call, Peter took Mark and went to preach in Rome. Later, somewhere between AD 58 and 61, Mark arrived alone in Alexandria as a humble, yet experienced evangelist.[13] As his sandals were torn because of long walks, he turned to a cobbler who, while fixing them, hurt his hand and cried, “God is one!” Mark saw in this cry a divine sign indicating the man’s readiness to receive the gospel. By God’s power, Mark healed Ananius, as the shoemaker was called. After believing in Jesus’ incarnation and salvation, Ananius and his family were baptised. Afterward, Ananius became the first indigenous bishop in Alexandria and his house was the meeting place of the first local church in Egypt. Some years later, around AD 68, when Mark visited the church of Alexandria and planted the seed of the Catechetical School of Alexandria, the local authorities captured him and brutally killed him by pulling him by his neck in the streets of the city.[14] Mark Oxbrow rightly notes, “Planting ecclesial communities of witnessing Christians was the core of Mark’s discipleship and ministry and in a sense a precursor of, if not a contributing factor to, his eventual martyrdom.”[15]

Martyrdom

Apparently, Mark’s martyrdom in Alexandria marked the path of the Egyptian church for centuries to come. From that day till now, martyrdom has never left the Coptic Church. Throughout history, a variety of cruel, pagan Roman rulers, some fanatic Chalcedonian Christians of Byzantium, and groups of extremist Muslim Arabs have all contributed to the persecution of the Copts.[16] It is not an overstatement to regard Coptic history as one of martyrdom.[17] Martyrdom, to bear witness with blood, is conceived as God’s gift bestowed to the church. “For it has been granted to you that for the sake of Christ, you should not only believe in him but also suffer for his sake” (Phil 1:29 RSV).[18] Offering oneself to die for Christ—which is the highest form of love and faith—requires a path of humility and obedience. That is why Matta El-Meskeen affirms that walking on the path of martyrdom is only possible when the believer fully and continuously surrenders to the Holy Spirit.[19] In this regard, Thomas Oden reflects:

No one generation can subdue the consent of the faithful. No century of persecution can defeat it, not even twenty centuries, as we see in Coptic Egypt. The Spirit promises to guard from permanent error the apostolic witness.[20]

The Coptic Church calls its liturgical calendar Anno Martyri, the year of the martyrs, and its New Year is the feast of the Martyrs. It is “a spiritual preparation for starting a new year.”[21] Commenting on the words of Tadros Malaty, Myrto Theocharous writes,

The Coptic Church calls its liturgical calendar Anno Martyri, the year of the martyrs, and its New Year is the feast of the Martyrs. It is “a spiritual preparation for starting a new year.”[21] Commenting on the words of Tadros Malaty, Myrto Theocharous writes,

One can only admire the faith and devotion of our Coptic brothers and sisters, not only to God, but to their community that transcends death. They call death “a new birth,” thus establishing an image in our minds that we, as Christians, … are carried in the darkness of the womb, only to be delivered into a new life, a transcendent life.[22]

A more recent example powerfully illustrates the witnessing through the blood of martyrdom. On 12 February 2015, the unbelieving world was deeply moved by the faith of the twenty-one martyrs who were slaughtered somewhere along the Libyan coast and died calling “Lord Jesus.”[23] Moreover, the whole world could see the martyrs’ families who appeared the following days forgiving and praying for the conversion of the perpetrators.[24] Mightily, the martyrs and their families celebrated the victory of their faith over the hatred of their enemies. Core Christian values like forgiveness, humility, and perseverance were in this way made evident in the life of the Copts more than their words at death.

Spread of Christianity in the land of Egypt

Although early believers in Egypt were most probably residents of Alexandria, with a majority being Hellenistic Jews, by the end of the second century the church had spread to encompass the wider population. Intriguingly, under one of the harshest periods of persecution during the reigns of Diocletian and Maximian, the Egyptian church grew considerably, as noted by Alan Kreider.[25] Based on traditional accounts and recent discoveries, Kreider has concluded that Egyptian Christians, through their position of weakness, were able to attract people from other religious backgrounds to join them.[26] Popular Egyptian Christian piety was therefore the attracting force of evangelism, rather than social, political, or financial power.

The conversion from paganism to Christianity of Pachomius the Great (292–348 AD), the father of Christian coenobitic monasticism, is a wonderful example of how the serving love and generous hospitality instinctively demonstrated by the marginalised Christian communities impacted the faith of non-Christians.[27] The story tells that Pachomius, then aged twenty (around 312 AD), was pressed into joining a military campaign.

As the conscripts were sailing downstream, the soldiers who were keeping them put in at the city of Thebes and held them in prison there. In the evening some merciful Christians, hearing about them, brought them something to eat and drink and other necessities, because they were in distress. When the young man asked about this, he was told that Christians were merciful to everyone, including strangers. Again he asked what a Christian was. They told him, ‘They are men who bear the name of Christ, the only begotten Son of God, and they do good to everyone, putting their hope in Him who made heaven and earth and us men.’ Hearing of this great grace, his heart was set on fire with the fear of God and with joy. Withdrawing alone in the prison, he raised his hands to heaven in prayer and said, ‘O God, maker of heaven and earth, if you will look upon me in my lowliness, because I do not know you, the only true God, and if you will deliver me from this affliction, I will serve your will all the days of my life and, loving all men, I will be their servant according to your command.’[28]

After he returned safely from that campaign and was released from the army, Pachomius was faithful to his promises, became a catechumen, was baptised, and went on his spiritual journey till he became the famous and inspiring Christian figure. All of that was because anonymous devout Christian women and men had acted generously in humility and love to strangers in distress.

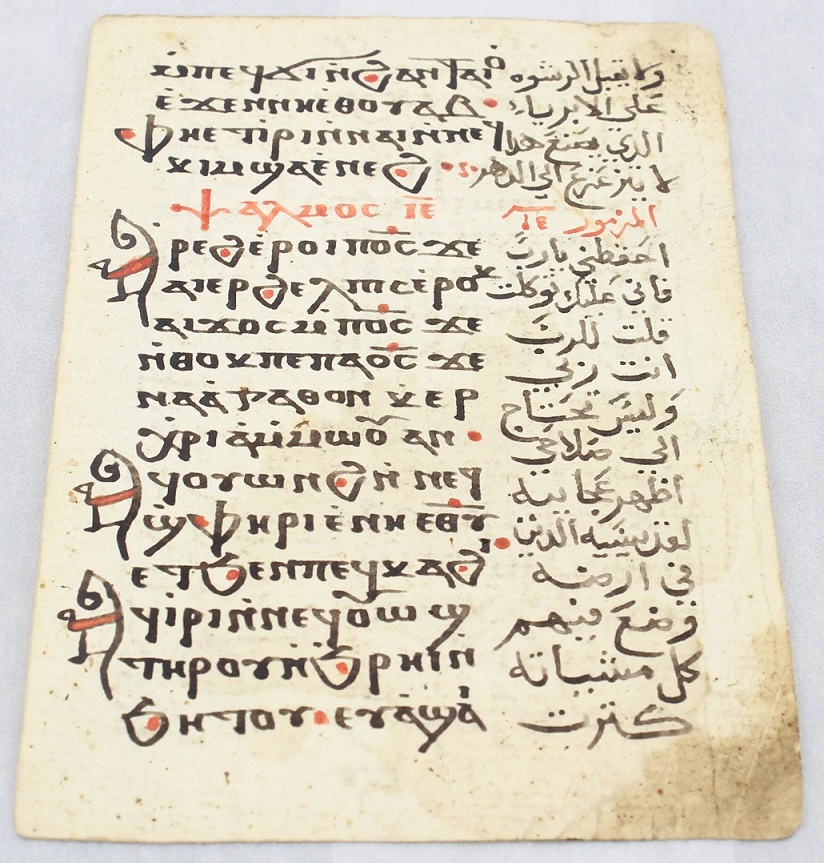

Bible translations and Christian worship

Christianity would not have spread all over the Egyptian lands and survived until this day without the Bible being translated into the local language and the people learning to worship in their mother tongue. Egyptians were predominantly bilingual, speaking Greek and Coptic. Greek was the lingua franca of those times, spoken mostly by those residing in cosmopolitan cities like Alexandria. Coptic, the latest development of the ancient Egyptian language, remained the language of the people, mainly in rural areas. Early Christians who were more familiar with Greek used the Septuagint as the Old Testament, since it was translated from Hebrew to Greek in Alexandria, and gradually adopted the books of the New Testament in their original languages. The growth of the church among Coptic-speaking Christians prompted the translation of the Bible into the vernacular. The Bible was then gradually translated into most Coptic dialects, especially during the times of the Coptic pope Demetrius, who was also known as the Vinedresser (189– 231 AD). It is widely accepted that “by the fourth century, the entire canon of the Old and New Testament books was translated in at least the main Coptic dialect.”[29]

Translating the Bible was not exclusively for catechetical purposes, but also for liturgical ones. Praying the Scriptures is the core of Coptic discipleship. Further, “the believers of the Coptic Church encounter the Bible mostly in its liturgical books, and that applies to the Old and New Testaments, both of which enjoy the same stature.”[30] The church’s orthodox doctrines are thus preserved in the people’s hearts through the thematic hearing of the Scriptures throughout the year, following certain cyclic lectionaries. On the personal level, the faithful are encouraged to read and meditate on the Word of God as God’s personal message for them,[31] and to pray the Psalms daily according to the Book of Hours (the prayer book of the Coptic Church).

Orthodoxy and heresy

It was expected for an active growing church like the Egyptian one to face, from its early age, strong waves of heresies (e.g., Gnosticism, Arianism, Nestorianism, Monophysitism). Nonetheless, these misinterpretations of the Scriptures and wrong understandings of foundational topics of Christianity, such as the Triune God, the incarnation, and salvation, were confronted by two interdependent forces: (1) Christian popular consciousness and piety, and (2) sound biblical and spiritual teachings. The first is nourished organically within Christian communities and families, while the second is strengthened in the churches and through theological education. This combination produced great figures who contributed to global Christianity in a way that still leaves us in their debt. During these early centuries, “Egypt [became] one of the most theologically fertile provinces in the history of Christianity. Persons, events, and institutions have exerted an influence which has extended beyond the limits of the country and has influenced the universal Church.”[32] To name a few of those figures: Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Didymus the Blind, Cyril of Alexandria, Antonius the Great, Pachomius, and Macarius the Great.

Among this cloud of witnesses, one name warrants special attention—Athanasius of Alexandria. Before becoming the twentieth pope and patriarch of Alexandria, Athanasius was one of the leading figures in refuting the Arian heresy. Because of his contribution in presenting the orthodox faith, Athanasius’s name has always been associated with the Nicene Creed which was issued during the ecumenical council held in 325 AD. Athanasius’s role as bishop and pastor is often overlooked in readings on church history. It is therefore important to note that Athanasius’s teachings were mostly liturgical and pastoral; he drew from the people’s spiritual encounters and sacramental experiences to defend the soteriological aspect of God’s mystery for the edification of his flock.[33] Reciprocally, the people loved him, supported him, and on many occasions protected him from his powerful adversaries, whether emperors or local rulers.[34]

For common people to demonstrate this kind of attitude was far from rare. Throughout Coptic history, the Egyptian believers acted as the defenders of the faith. At times, they would support their leaders, but at other times, when the leaders deviated from the orthodox spirit and doctrine, they would stand firmly against them. Somehow, their Christian popular consciousness was well-trained by God’s Spirit and Word to discern orthodoxy from heterodoxy.

Early monasticism

One additional significant contribution of the Coptic Church to God’s mission is monasticism with its various forms. Organised monasticism started in the Egyptian deserts. Thousands of men and women filled with God’s love obeyed the Spirit’s special calling and lived radically by the gospel and for the gospel. Living by the gospel is perhaps evident in the way early monks and nuns in Egypt structured their lives. They sold their properties if they had any, lived modestly with barely the necessities, and consecrated their time for praying, meditating on the Scriptures, and engaging in manual labor. Living for the gospel, however, often goes unnoticed by outsiders. The primary role of monks and nuns is to intercede for the rest of the church and the suffering world. The fruits of their labour go to cover their basic needs and the rest is offered to the poor.[35] In some orders, the monasteries’ responsibility is to offer humanitarian aid to the needy, orphans, widows, and strangers to their region.[36] Additionally, they may support the church in defending the faith,[37] and, when needed, evangelising where no one could go.[38] It was through Egyptian monastics that Nubia and Ethiopia were Christianised. Moreover, evidence suggests that Coptic monks evangelised Ireland and other Western nations.[39]

Seventh to nineteenth century

The Arab invasion of Egypt (AD 641) was a turning point in Coptic history.[40] The series of dramatic geopolitical changes that happened from the seventh century onwards had a strong impact on the Coptic contribution to God’s mission that would last for over twelve centuries. In this regard, Arabic and then Ottoman rule over Egypt closed some doors and opened new avenues for the Coptic witness to walk in.

From Coptic to Arabic

Gradually, the Egyptian community had to adapt itself to the new language brought by the invaders—Arabic. As Arabic became the political and commercial language, Egyptians had to give up their Coptic language, sacrifice their linguistic heritage, and adopt the new language in order to keep their jobs and social status. Within the Christian community, however, a more resistant approach took place. The church became the last refuge for the Coptic language. Prayers, hymns, and Scriptural readings in Coptic have survived until today with some remnant Greek.

Nonetheless, after a few centuries, when the new Coptic generations ceased to understand and communicate using Coptic, the church had to provide an Arabic translation of all its biblical and liturgical books and put them in use for the congregation to be engaged in the services.[41] On another level, this transition from Coptic to Arabic played a pivotal role in the church’s interaction with the new-arriving culture.

Christian-Muslim dialogue

The coming of Arabic Islam into the Egyptian Christian lands created a fresh theological encounter, an encounter between Christians and Muslims. Copts had, for centuries, held theological conversations with pagans, Jews, and Christians from other traditions. Under Arabic rule, their conversation partners come from a completely new religion and culture. As a result, they needed a profound grasp of the challenging new ideas coming to their lands so they could rightly respond using common language and logic. Numerous deep religious and philosophical dialogues were carried out, in Arabic, between scholars from both sides on topics of agreement and disagreement, such as the possibility of the incarnation, God’s oneness and trinitarian nature, fate and free will, the inspiration of Scripture, and many other topics.[42] It is worth noting that those debates were often far from antagonistic and were at times friendly.

Furthermore, in Cairo, towards the end of the tenth century, the Al-Azhar Mosque and its scholar annexes began to stand as one of the most influential centres for Islamic learning, first following Shia Islam. Then, under Saladin (twelfth century), it was converted into Sunni Islam. Scholars from around the world came to Cairo to learn, study, and research Islam. In this context, Christian Arabic literature of that time was not limited to apologetics, but also served to edify the Arabic-speaking churches in general and evangelise when possible. By the thirteenth century, the church of Egypt stood as the leading church in producing Christian literature in Arabic. During this period, some remarkable Coptic scholars led the movement of “manuscript discovery, copying, translating, and original composition of Christian theology in Arabic.”[43]

Socioeconomic pressure

Apart from innovative intellectual activities, Christian Egyptian social life also underwent serious changes. The occupiers’ laws brought unexpected long-lasting socioeconomic pressure on the Copts who were considered Dhimmis.[44] For example,

Dhimmis were required to disarm completely and to submit to Muslim rule. Any person found to be armed was either killed or enslaved. Second, Dhimmis were allowed to practice their own faith within churches or synagogues established prior to the advent of Islam, but building of new religious houses was prohibited. It was understood that liturgies would be performed quietly, without ostentation or the organization of open processions or any other function that might prove offensive to Muslims. Each community was under the hegemony of a religious leader answerable to the Muslim governor. Throughout the Middle Ages, Coptic patriarchs bore the burdens of the community vis-à-vis the Muslim caliph, sultan, or governor.[45]

Furthermore, Arabs and Ottomans forced the jizyah (poll tax) on subject nations that did not convert to Islam. Originally, jizyah was a type of extra tax that was imposed exclusively on non-Muslims in return for providing military security, since the army could not include unbelievers. Gradually, it became the only possible way for the Copts to escape from prison, death, or conversion to Islam. Often, local rulers had to induce their superiors, whether sultans or kings, to maintain their position of subservience. Hence, under corrupt rulers, the jizyah was driven higher and higher. As a result, the Copts had by the fourteenth century ended up as an impoverished numerical minority in Muslim-dominated Egypt, as they had been before the fourth century.[46] Moreover, on many occasions, riots would break out and the Christians’ properties and churches would be destroyed.[47] For instance, “the annalist al-Sakhawi stated that (in the year 1448) no church in Egypt escaped some destruction.”[48] Of course, this kind of violence varied in intensity throughout the centuries depending on the rulers’ tolerance for Christianity and their understanding and implementation of Sharia law. As for the Copts, usually, the money left after paying the jizyah in addition to other types of taxes would typically be spent on supporting their fellow Copts in their immediate needs, and if they had a small sum left to donate to the church, it would go to the support of the clergy and the maintenance or reconstruction of church buildings if local authorities permitted. It was not until 1855 that the jizyah was officially abolished as part of national political reforms.[49]

Foreign missions in Egypt

Towards the end of that era, when Egypt gained partial independence from the Ottoman Empire, the Albanian ruler of Egypt, Mohamed Ali (1769–1849), began to open the country for foreign Christian missions, Catholic and Protestant, to settle in. Most probably, this step was one of the initiatives of Ali’s dynasty (1805–1952) intended to strengthen its political and economic ties with European powers.[50] During that time, Western missions were closely related to colonialism since they mutually benefited from each other. Due to their missional zeal, some mid-nineteenth century European churches saw in the new conditions golden opportunities to spread their presence in the Egyptian lands. Contemporary history of Western missions shows that European and later American missions came to Egypt based on misleading prejudices, namely that Copts are heretics, practitioners of superstitions, and at best nominal Christians. In this regard, Western Christianity has failed, to a certain extent, to grasp the primarily spiritual and experiential Christianity that was alive in Egypt, having in mind their predominantly rational and intellectual Christianity coming out from the Enlightenment period. Further, by doing so, they disregarded the struggle the Coptic Church had to suffer for its survival throughout its long history. Interestingly, when they were unsuccessful in converting Muslims to Christianity, as it was their primary goal, some foreign missions turned their aims to convert Coptic Christians to their own denomination. In the end, instead of learning from them, Western missionaries approached the Copts as objects of study or conversion. Nonetheless, a few Western missionaries chose to cooperate with the local Coptic church with mutual respect and appreciation, especially in providing affordable versions of the Bible, and in poor places, offering substantial humanitarian aid.[51]

Twentieth century till today

The end of the nineteenth and the dawn of the twentieth century witnessed another significant change in the Copts’ socioeconomic conditions in Egypt. Some civil restrictions have been loosened for the Copts, thus allowing them to contribute anew to God’s mission. Refusing to be treated as a minority group in their own land, “the Coptic community has been an important and peaceful agent of cultural, economic and political change.”[52]

Sunday School Movement

At that time, two major movements emerged to renew Coptic witnessing. First, the colonial attitude of foreign missions in Egypt urged the Copts to stand for their forefathers’ faith as they had from the early centuries while facing new challenges and using modern tools. Second, taking advantage of some freedom provided by the new political, social, and economic reforms, Copts took part in waves of revival beginning with its own people. This does not mean that the Coptic Church lost its way and needed conversion; instead, like any church in this world, it needed continuous renewal by the Spirit so that its witness can remain relevant to the current context. It is unfair to limit the credits of revival to certain individuals, as has often been the case in historical records. In Egypt, the nameless multitude of devout people were the heroes and bearers of a profound faith. If any name has come up to lead some aspects of the church’s renewal, it is because of the prayerful life of a mother, the sacrifice of an older brother, the hospitality of a younger sister, or the modesty of an unknown stranger.

That renewal was exhibited through an active discipleship built on two intertwined streams: spiritual formation and theological teaching. In this regard, one of the most significant initiatives is the Sunday School Movement. Well-prepared, educated, and committed youth went to almost every neighbourhood in Egypt establishing catechetical classes. These youth were led by Archdeacon Habib Guirguis and mentored by Father Mina El-Baramosy (who later became Pope Kyrillos VI).[53] In the beginning, this movement was not welcomed by many clerics. By now, however, after more than a hundred years from its beginnings, it is nearly impossible to find a Coptic Church without a Sunday School program for children and youth.[54] Anthony O’Mahony notes that

the Coptic Church stresses family life and strives to draw groups from different social strata, ages, and levels of education into the Church system. Hence there are groups for women, youth, and different age groups for children, university students, young couples, and the like. Service to the Church and a social life that rallies around the church has become central for most Copts.[55]

Besides stressing conscious participation in the church’s mysteries, the catechetical program is usually based on yearly reflection on topics such as biblical studies, Christian ethics, church dogmas, liturgical formation, church history, hymnology, Coptic language, and many other subjects. Sunday School programs are structured in a way to prepare church servants to lead the movement when they reach the appropriate age and level of Christian formation. In addition, regular home visitation is one of the foundational cornerstones of Coptic witnessing. It reflects the profound conviction of pastoral care. Furthermore, the logistics of the whole movement depends on self-funding. Until today, Sunday School teachers in Coptic churches are volunteers who devote most of their weekends and weekday evenings for the service of the church.

Migrating Church

In the second half of the twentieth century, waves of Coptic emigration due to economic, social, or political reasons resulted in the formation of new Coptic communities and churches in Europe, North America, and Australia. Responding to the requests of those communities, the mother church in Egypt sent priests to provide pastoral care to the Copts in their new homes rather than to evangelise in new territories.[56] In every church, priests depended on local church servants to implement Sunday School programs among other activities with special attention given to children and youth. As happened in Egypt a millennium ago, churches in the lands of emigration engage in cultural conservation. Newly formed churches do not provide spiritual care only, but they become in most places “the primary and most important place of Coptic social (and cultural) life.”[57] Nevertheless, Copts gradually began to integrate into society and interact with the wider community in social and political activities. In the last two decades, Copts who were born in the lands of emigration have been ordained priests or bishops and have begun to reflect on their responsibility to witness in these communities. In this way,

Migration has placed Copts in a position of dialogue and explanation regarding their faith, forcing the Coptic Church to formulate its identity in a more pluralistic context rather than against Islam alone. The diaspora has expanded the sphere of Coptic influence in new contexts by encouraging the concretising of identity and the extended hand of ecumenical outreach.[58]

Accordingly, with the blessings of the mother church in Egypt, “missionary-focused” churches were born out of the traditional ones, to reach out to people from different backgrounds and cultures. One of the pressing questions being discussed among the leaders of those churches is what Coptic identity would look like in their multicultural communities.[59]

Evangelistic initiatives

With the freedom of movement that Copts began to enjoy in the twentieth century, and due to their exposure to other nations, cultures, and religions, they began to discern the need and the opportunity to engage in spreading the gospel outside their traditional borders. In fact, moving in an evangelistic direction came first as an answer to African requests. As early as 1918, some Kenyan, South African, Nigerian, and later Congolese independent churches approached the Coptic Church in Egypt asking to join it. It is worth noting that the Coptic Church was an underprivileged church, devoid of attractive financial or political power. Nonetheless, the African Christians were attracted to it because they saw in the Coptic Church an African church, an authentic orthodox and apostolic church, the historical church of Alexandria, and believed that it would not serve colonial purposes nor would it show the slightest trace of racial discrimination.[60] Without hesitation, Copts were prompted to respond to their neighbours’ calls. However, due to political considerations and economic limitations, early attempts failed. Sustainable actions were delayed until the 1960s. Since then, long-term visits, discipleship programs, and liturgical, diaconal, and clerical training in those places resulted in the permanent establishment of tens of local churches and communities in these countries and other African nations.[61]

Towards the end of the twentieth century, other evangelistic steps took place in Latin America. Monks were originally sent to pastor some Egyptian communities in Brazil, Bolivia, and Mexico. While living there, they began to discern the need to widen their service to include locals, from these countries and beyond, who were not part of any other Christian community. Consequently, Coptic communities in Latin America are composed mostly of locals.[62] A decade ago, a similar process took place in some Asian countries, such as the Philippines, South Korea, Indonesia, and Japan.

Wherever the Coptic Church goes, the servants use the most common Bible translation available, and they translate the liturgical books into the vernacular. Furthermore, in most places, Coptic witness often takes a holistic approach. Metropolitan Serapion’s views can represent the Coptic Church’s understanding of holistic service. He says, “The Coptic Orthodox Church is not merely a school involved in research work and teaching dogma, but also an institution that worships God and serves mankind. It works for the renewal of this world, and hopefully awaits for the world to come.”[63]

Epilogue: Missional reflection

This brief historical overview shows how diverse the forms of Coptic witnessing are. Throughout the past two thousand years, the Coptic Church has experienced significant developments and shifts in its contribution to God’s mission while the Holy Spirit has been building up its unique personality.

The foundational story of Mark the apostle reveals how, on the personal level, one’s submission to God’s call within an ecclesial environment is the basis of missional work. Further, the servants’ inner and outer vulnerability is key to planting the seed of faith in people. This voluntary, and in many cases obliged (such as when under foreign rulers), vulnerability remains one of the Coptic features of witnessing that proves well that God’s power is manifested through weakness (2 Cor 12:9). From the locals’ point of view, a mission that starts from below, from the margins, from the lower strata, from the working class, as happened with the shoemaker, has the potential to become more rooted and indigenised.[64]

Closely related to the rootedness of faith is the organic church growth that helped spread and reinforce the Christian faith in the Egyptian lands. As an often-repressed community, the Coptic Church in most of its history was primarily concerned about the survival of its believers’ faith and less concerned with sharing the verbal gospel beyond its borders. Yet, Copts maintained their faith and their witness is alive and flourishes as they fulfil the Great Commandment: Love your God and your neighbour. Under severe circumstances, Egyptian Christians tried in every possible way to engage positively with their neighbours, mostly by their deeds and, when possible, by words. In any case, the incarnate love continues to be the driving force of Coptic witnessing. Thus, loving God and the neighbour, or, better said, loving God in the neighbour can perhaps summarise the Coptic understanding of mission. Serving out of love in any possible way is the fruit of knowing and receiving God’s love. This love should remain the attracting force for other people to believe in Christ and join the church.

The same love was shown in the church’s treatment of the issue of languages: from Greek and Coptic to Arabic, and recently to numerous modern languages. From its very beginning until this day, the Coptic Church expressed flexibility, care, and priority for the gospel to be comprehended by its people, instead of maintaining a language that is alien to the congregations’ minds. Having said that, it remains the Copts’ responsibility to preserve the richness of the church’s legacy for the coming generations to learn from.

Looking at the continuously changing world, it becomes evident that Copts have a duty to refashion once again their tools of reading and interacting with the new contexts in which they live. On the one hand, without forgetting their past, Copts need to remain attentive to the signs of the times and discern how to respond contextually to current challenges. On the other hand, it is painful to see certain Coptic evangelistic initiatives uncritically adopt colonial Westernised approaches to mission. Therefore, since most Coptic servants are more doers than reflectors, perhaps, while they care for their Coptic rootedness, they also need some training so that they gain awareness in terms of research skills and contemporary methodologies. This may perhaps influence other Christians as well and will enhance the ecumenical relationships that the world needs now more than ever.[65]

In the end, Coptic witnessing is historically a popular ecclesial witnessing. It is not the task of certain individuals but of the whole body of Christ. That is one of the reasons why the Coptic Church is often reluctant to adopt the word mission in its ecclesial vocabulary. Instead, they prefer to use words like service, discipleship, and witnessing to express the church’s organic evangelistic responsibility. In that sense, children of light cannot help but shine, even if they are enclosed in a dark prison or worship in a remote desert. Thus, the primary goal of Coptic discipleship is the continuous transformation of its people through the work of the Holy Spirit so that they are shaped into the image and likeness of Jesus Christ, knowing that becoming like him is the only way to redeem the world and extend God’s Kingdom.

[1] Parts of this article appeared in Riad Ghobrial, “Rethinking or Rediscovering a Theology of Mission? A Response to the Current Challenges of Coptic Orthodox Missiology,” Salt: Crossroads of Religion and Culture 2 (2023). The focus there is more on the contemporary mission work and is supplementary to this article.

[2] The word Coptic is a derivative of the Greek word Aigyptos which refers to native Egyptians and their language. After the Arab invasion, it refers to the Egyptian Christian community.

[3] Cf. Henning Wrogemann, Intercultural Theology, Volume Two: Theologies of Mission (Downers Grove: IVP, 2018), 380.

[4] Exploring two thousand years of history in a short article unavoidably entails some sort of reductionism.

[5] Cf. David J. Bosch, Transforming Mission: Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission, 20th anniversary ed. (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2011).

[6] Herodotus, The Histories, II, 37, trans. George Rawlinson (Moscow, ID: Roman Roads Media, 2013), 111.

[7] Cf. C. Wilfred Griggs, Early Egyptian Christianity: From Its Origins to 451 CE (Leiden: Brill, 2000), 17.

[8] In these two accounts, the believers were Egyptian Jews known as diasporic or Hellenistic Jews.

[9] Acts 12:25, 13:5; 2 Tim 4:11; 1 Pet 5:3. Coptic tradition identifies John Mark as the same person mentioned in those verses.

[10] Eusebius of Caesarea, The Ecclesiastical History, 16:1–2.

[11] Coptic tradition holds that Jesus celebrated his last Passover in Mark’s mother’s house and that it is the same house that hosted the disciples after the resurrection and during the events of the Pentecost.

[12] Sāwīrus ibn al-Muqaffa’, History of the Patriarchs of the Coptic Church of Alexandria, Part 1: St. Mark – Theonas (300 AD), Patrologia Orientalis 1, ed. and trans. Basil Evetts (Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1904), 141.

[13] Pope Shenouda III, The Beholder of God: Mark the Evangelist, Saint, and Martyr, trans. Samir F. Mikhail and Maged S. Mikhail (Santa Monica, CA: St. Peter and St. Paul Coptic Orthodox Church, 1995), 43.

[14] Thomas C. Oden, The African Memory of Mark: Reassessing Early Church Tradition (Downers Grove: IVP, 2011), 157–59.

[15] Mark Oxbrow, “Mission and Martyrdom: A Reappraisal of Mark in African Context,” in Living the Gospel of Jesus Christ: Orthodox and Evangelical Approaches to Discipleship and Christian Formation, ed. Mark Oxbrow and Tim Grass, Regnum Studies in Mission (Oxford: Regnum, 2021), 199.

[16] E. Amelineau, Les Actes des Martyrs de L’Eglise Copte: Etude Critique (Paris: Imprimerie Daloux, 1890), 1; Arietta Papaconstantinou, “Historiography, Hagiography, and the Making of the Coptic ‘Church of the Martyrs’ in Early Islamic Egypt,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 60 (2006): 65–86.

[17] Maged S. A. Mikhail, From Byzantine to Islamic Egypt: Religion, Identity and Politics after the Arab Conquest (New York: I. B. Tauris, 2014), 133–34.

[18] Matta El-Meskeen, Martyrdom and Martyrs: A Spiritual Study (Arabic), 3rd ed. (Scetis, Egypt: The Monastery of St Macarius, 1987), 9–10.

[19] El-Meskeen, Martyrdom and Martyrs, 55–56.

[20] Thomas C. Oden, The Rebirth of African Orthodoxy: Return to Foundations (Nashville: Abingdon, 2016), 57.

[21] Tadros Y. Malaty, Introduction to the Coptic Orthodox Church (Alexandria: St. George Coptic Orthodox Church, 1993), 27.

[22] Myrto Theocharous, “Understanding the Blessing of Persecution: Reflections on Philippians,” in Living the Gospel of Jesus Christ: Orthodox and Evangelical Approaches to Discipleship and Christian Formation, ed. Mark Oxbrow and Tim Grass, Regnum Studies in Mission (Oxford: Regnum, 2021), 211.

[23] Martin Mosebach, The 21: A Journey into the Land of Coptic Martyrs (Walden: Plough, 2020), 11. Twenty martyrs were from Egypt and one was from Ghana. They were all simple workers.

[24] Mark Woods, “‘The 21:’ The Story of the Coptic Christian Martyrs,” Christian Today, 15 February 2019, https://www.christiantoday.com/article/the-21-the-story-of-the-coptic-christian-martyrs/131772.htm (accessed 28 February 2024).

[25] Alan Kreider, The Patient Ferment of the Early Church (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2016), 246–47.

[26] Kreider, The Patient Ferment, 247.

[27] Kreider, The Patient Ferment, 116–17.

[28] First Greek Life of Pachomius, 4–5; Pachomian Koinonia Volume 1: The Life of Saint Pachomius and His Disciples, trans. Armand Veilleux (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian, 1980), 300.

[29] Hany Takla, “The Coptic Bible,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Bible in Orthodox Christianity, ed. Eugen J. Pentiuc (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022), 83.

[30] Riad Ghobrial and Myrto Theocharous, “The Bible in the Coptic Tradition,” in Your Word is Truth Volume 2: The Bible in Christian Traditions, ed. Rosalee Velloso Ewell, Ani Ghazaryan Drissi Gunnar Mägi, Vasile-Octavian Mihoc, and Lyn van Rooyen (Swindon: United Bible Societies and Geneva: World Council of Churches, 2023), 97.

[31] Matta El-Meskeen, The Communion of Love (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary, 1984), 16–17; Matta El-Meskeen, “The Bible as a Personal Message to You,” http://www.coptics.info/Frmatta/The_bible_as_a_personal_message_to_you.htm (accessed 28 February 2024).

[32] Fernand Cabrol and Henri Leclercq, Dictionnaire d’archéologie chrétienne et de liturgie, Tome IV (Paris: Librairie Letouzey et Ane, 1921), 2401.

[33] George Habib Bebawi, The Role of Liturgy in Laying the Eastern Theological Foundation (Arabic), (Cairo: Coptology, 2012), 4; Cf. Jaroslav Pelikan, The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine, Vol. 1: The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1975), 217.

[34] Samuel Sharpe, Egyptian Mythology and Egyptian Christianity, With Their Influence on the Opinions of Modern Christendom (London: John Russell Smith, 1863), 104, 108; David M. Gwynn, Athanasius of Alexandria: Bishop, Theologian, Ascetic, Father (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 131.

[35] Bentley Layton, “Social Structure and Food Consumption in an Early Christian Monastery: The Evidence of Shenoute’s Canons and the White Monastery Federation A.D. 385–465,” Le Muséon 115 (2002): 25–55.

[36] As in the Pachomian monasteries. It is recorded that Pachomius’s death was caused by an infection that was transmitted to him as a result of caring for patients during an epidemic that was raging in his time.

[37] For example, we learn that during the Arian tensions, Anthonius the Great left the desert and went to Alexandria to support the believers.

[38] A contemporary treatment of the relationship between monasticism and mission can be consulted in Athanasios N. Papathanasiou, “Monastics as Missionaries of a Subversive Hope,” International Journal of Orthodox Theology 13, no. 1 (2022): 9–27.

[39] Robert K. Ritner Jr., “Egyptians in Ireland: A Question of Coptic Peregrinations,” Rice Institute Pamphlet -Rice University Studies 62, no. 2 (1976): 65–87.

[40] Cf. Sabine R. Huebner, Garosi Eugenio, Isabelle Marthot-Santaniello, Matthias Müller, Stefanie Schmidt, and Matthias Stern, Living the End of Antiquity: Individual Histories from Byzantine to Islamic Egypt (Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, 2020).

[41] Jason R. Zaborowski, “From Coptic to Arabic in Medieval Egypt,” Medieval Encounters 14, no. 1 (2008): 15–40; Adel Sidarus, “From Coptic to Arabic in the Christian Literature of Egypt (7th–11th centuries),” Coptica 12 (2013): 35–56.

[42] Cf. Johannes Den Heijer, “Apologetic Elements in Coptic-Arabic Historiography: The Life of Afraham ibn Zur’ah, 62nd Patriarch of Alexandria,” in Christian Arabic Apologetics during the Abbasid Period, (750–1258), ed. Samir Khalil Samir and Jorgen S. Nielsen (Leiden: Brill, 1993), 192–202; Ann Giletti, “An Arsenal of Arguments: Arabic Philosophy at the Service of Christian Polemics in Ramón Martí’s Pugio fidei,” in Mapping Knowledge: Cross-Pollination in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, ed. Charles Burnett and Pedro Mantas-España (Cordoba and London: CNERU – The Warburg Institute, 2014), 153.

[43] Sidney H. Griffith, The Church in the Shadow of the Mosque: Christians and Muslims in the World of Islam (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007), 65.

[44] Dhimmis referred to Christians and Jews who agreed to live in Muslim territories.

[45] “Ahl Al-Dhimmah,” in The Coptic Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, ed. Aziz Suryal Atiya (New York: Macmillan, 1991), 72–73.

[46] Shaun O’Sullivan, Coptic Conversion and the Islamization of Egypt (Chicago: The Middle East Documentation Center in Chicago, 2006), 65.

[47] Bengt Sundkler and Christopher Steed, A History of the Church in Africa (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 20.

[48] “Mamluks and the Copts,” in The Coptic Encyclopedia, Vol. 5, ed. Aziz S. Atiya (New York: Macmillan, 1991), 1517–1518.

[49] Febe Armanios, Coptic Christianity in Ottoman Egypt (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 151.

[50] Armanios, Coptic Christianity in Ottoman Egypt, 151.

[51] For more details about the complexity of the relationship between Copts and Western missionaries, please refer to Alastair Hamilton, The Copts and the West, 1439–1822: The European Discovery of the Egyptian Church, Oxford-Warburg Studies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006); Paul Sedra, From Mission to Modernity: Evangelicals, Reformers and Education in Nineteenth Century Egypt (London: I. B. Tauris, 2011); Tim Grass, “Evangelicals and Eastern Christianity,” in The Routledge Research Companion to the History of Evangelicalism, ed. Andrew Atherstone and David Ceri Jones (London and New York: Routledge, 2018); Heleen Murre-van den Berg, New Faith in Ancient Lands: Western Missions in the Middle East in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries, Studies in Christian Mission (Leiden: Brill, 2007).

[52] Anthony O’Mahony, “The Coptic Orthodox Church in Modern Egypt,” in Eastern Christianity in the Modern Middle East, ed. Anthony O’Mahony and Emma Loosley (London: Routledge, 2009), 56.

[53] For more details about these two figures, see Bishop Suriel, Habib Girgis: Coptic Orthodox Educator and a Light in the Darkness (Yonkers, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2017); and Daniel Fanous, A Silent Patriarch: Kyrillos VI Life and Legacy (Yonkers, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2019).

[54] It is worth noting that during the lifetime of Guirguis, the Sunday School Movement reached the Coptic dioceses in Sudan. The Coptic Sunday School Movement also influenced other renewal movements in Ethiopia and beyond. See Ralph Lee, “Discipleship in Oriental Orthodox and Evangelical Communities,” Religions 12, no. 5 (2021): 320.

[55] O’Mahony, “The Coptic Orthodox Church in Modern Egypt,” 76.

[56] Wedad Tawfik, “Discipleship Transforming the World: A Coptic Orthodox Perspective,” International Review of Mission 106, no. 2 (2017): 273.

[57] Sara Lei Sparre, Alistair Hunter, Anne Rosenlund Jørgensen, Lise Paulsen Galal, Fiona McCallum, and Marta Wozniak, Middle Eastern Christians in Europe: Histories, Cultures, and Communities (St. Andrews: University of St. Andrews, 2015), 11.

[58] D. A. Ogren, “The Coptic Church in South Africa: The Meeting of Mission and Migration,” HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 70, no. 1, Art 2061 (2014): 3.

[59] Fr. Michael Sorial, Incarnational Exodus: A Vision for the Coptic Orthodox Church in North America (Washington, DC: Agora University Press, 2020), 41–42; Shereen Marcus, An Immigrant Church No Longer: Reshaping Youth Ministry for Coptic Churches in North America (Washington, DC: Agora University Press, 2020), 19–20.

[60] Cf. David B. Barrett and T. John Padwick, Rise Up and Walk: Conciliarism and the African Indigenous Churches, 1815–1987 (Nairobi: Oxford University Press, 1989), 33. There is an increasing interest among Sub-Saharan African scholars in Coptic Christianity and its links with the rest of African Christianity. See for example, Victor Masilo S. Molobi, “Drawing a Connection between Coptic Christianity, Their St Mark Tradition, and Contemporary AICs: A Conversation with Coptic Bishop Markos,” Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae 44, no. 1 (2018): 1–16; Agai M. Jock, “The Coptic Origins of the Yoruba,” Theologia Viatorum 45, no. 1, a124 (2021).

[61] Today, the Coptic Church is present in more than eighteen African countries. Rf. Pope Tawadros II, ‘The Church and Africa’ (Arabic), in Al-Kiraza (27–28) (Cairo: Coptic Orthodox Patriarchate, 2019), 3.

[62] Here, Coptic began to refer to the church’s faith and not necessarily the nationality.

[63] Quoted in Tawfik, “Discipleship Transforming the World,” 275.

[64] Some hold that the disappearance of the churches in North Africa was due to its lack of indigenisation. Cf. Philip Jenkins, The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 21.

[65] In the last two decades, serious initiatives took place seeking better cooperation between the churches based on friendship, respect, and mutual understanding. For example, see David P. Teague and Ralph Lee, eds., Turning Over a New Leaf: Evangelical Missions and the Orthodox Churches of the Middle East (Oxford: Regnum, 2021); Kenneth R. Ross, Jooseop Keum, Kyriaki Avtzi, and Roderick R. Hewitt, Ecumenical Missiology: Changing Landscapes and New Conceptions of Mission (Oxford: Regnum, 2016).