If you can tell the difference between Jack Hawkins and John Mills, and between a Stuka and a Sten gun, perhaps after long, wet afternoons watching black-and-white war films, this is the book for you. Max Hastings is a wily operator who knows exactly what his readers want and with Operation Pedestal he has produced it for them again. The latest book off the apparently unstoppable Hastings conveyor belt tells the dramatic story of one of the most ambitious and dangerous naval operations of the war, and tells it well.

Malta, an island slightly smaller than Birmingham, sits at the crossroads of the Mediterranean, 60 miles south of Sicily. A base for the Royal Navy since Napoleonic times, during the second world war it was well positioned for interdicting German and Italian supply lines feeding Rommel’s forces fighting the British and Commonwealth Eighth Army in North Africa.

By the summer of 1942, however, the island had been bombed almost flat. Unable for the moment to do much more than defend itself, it was all it could do to hold out. But hold out it must. To lose Malta, said Churchill, would be ‘a disaster of first magnitude to the British Empire, and probably fatal in the long run to the defence of the Nile Valley’. Neither Churchill personally, nor Britain, could afford another shameful surrender such as had recently taken place at Tobruk and Singapore.

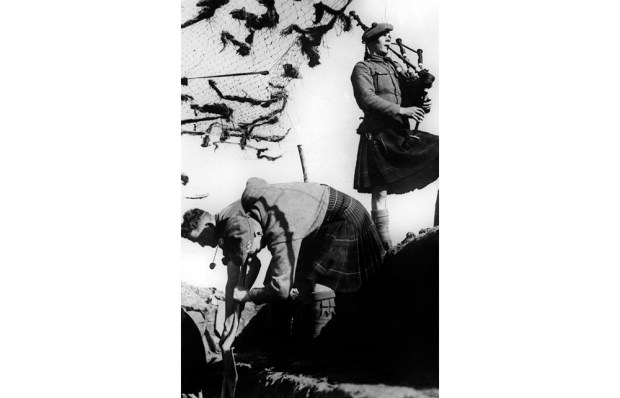

Starving people, however, cannot hold out indefinitely Several convoys had fallen victim to Axis aircraft, submarines and fast attack boats. Provisions were running dangerously low. Civilians pointedly rubbed their stomachs as the governor cycled by. Food, fuel and ammunition simply had to get through or the island would be forced to raise the white flag. The Royal Navy assembled a convoy of 14 fast merchant ships, packed with supplies and escorted by one of the most powerful fleets of the war. This included two battleships, four of Britain’s seven aircraft carriers, and nearly 20,000 men, determined to fight their way through at all costs.

This was Operation Pedestal, one of the most intense naval battles of the second world war. Over the course of just 48 hours, German and Italian aircraft, motor torpedo boats and submarines launched no fewer than 12 attacks on the British fleet. I won’t spoil the ending, but Hastings captures the violence, terror and horror of the fighting as vividly as ever. The accounts of survivors hearing the screams of drowning stokers, trapped in the engine rooms of sinking ships, are haunting.

Most of the time Hastings’s prose rattles along briskly enough to distract the reader from the occasional repetition and cliché. Some phrases really needed more care, though. To say that Albert Kesselring was ‘an ardent, if non-ideological Nazi’, for example, seems either meaningless or contradictory. In either case it is an odd way to describe a man who was sentenced to death for the massacre of 335 Italian civilians in 1944. Still, it’s a cracking story, and if you liked Hastings’s other books, you will enjoy this. I couldn’t put it down.

Yet Operation Pedestal was much more than a tale of derring-do. It lies at the centre of a number of interesting debates about the second world war. The summer and autumn of 1942 was a crisis point. It saw the initiative swing away from the Axis to the Allies, setting the pattern for the rest of the war. But we get little sense here of how Pedestal affected the fighting in north Africa,or the ongoing strategic debates in London and Washington about how to launch the second front. Further, the battle for Malta tested both sides’ ability to work with allies, and to integrate air-, sea- and land-power in revolutionary new ways. In that sense, it represents the Mediterranean campaign, and indeed the whole wider second world war, in miniature. The skills being learnt, often very expensively, in 1942 were critical to the outcome of the war. Capturing this broader picture would have made an exciting book interesting, too.

That, however, is not Hastings’s game. No doubt this book will encourage many to go off and read more history for themselves. Few can have inspired as many readers to do so as he has. After some dull years, we now live in a golden age of second world war history. Authors such as Daniel Todman, Jonathan Fennell and Alan Allport are finding thrilling new ways to tell the apparently stale tale of Britain’s war. If Operation Pedestal stimulates more people to pick up their books, well then, we’ll really be sucking diesel.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.