Christopher Walken Thinks Heaven's Gate Got More Hate Than It Deserved

Christopher Walken always disagreed with the mostly negative critical response to 1980's "Heaven's Gate." He plays a supporting role in the legendary flop of a Western, giving one of his most subdued and haunting performances as the morally-conflicted cattle baron enforcer Nate Champion. Walken had only just won an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor in director Michael Cimino's previous film, "The Deer Hunter," when the pair reunited for "Heaven's Gate." He couldn't have known what he was getting into.

He stands by it, however. As he told IndieWire in 2012, Walken "always thought it was good" and that the hate it received was undeserved. To critics like Vincent Canby of the New York Times, the film was "an unqualified disaster," one with flimsy themes and shoddy craftsmanship unbecoming of a filmmaker with such strong ambition as Cimino. Stories of the movie's troubled production and massive budget had been public knowledge since its first week of filming.

The poettry of Cimino's controversial 1978 Vietnam film "The Deer Hunter" was suddenly perceived as a fluke after "Heaven's Gate." Canby was just one of many critics who called the movie shallow, pretentious, and overlong. It was a disaster, with disastrous consequences for the film industry.

Still, Walken told IndieWire he felt that "Heaven's Gate" was "disproportionately beat up at the time, including by people in the business. I never understood that." To watch the movie now in its restored four-hour director's cut, it's easier to see the intention and majesty of Cimino's vision — one that was obscured by industry gossip in 1980.

The Johnson County War

Like many epics (misunderstood or not) of its era, "Heaven's Gate" uses its milieu –- rendered lovingly in specific, eccentric detail –- as a means of exploring larger questions about America. In particular, it deals with the circumstances of European immigrants in the West, zeroing in on the punishing struggles and minimal rewards of their new lives.

The movie dramatizes the real-life Johnson County War (the film's original title according to Peter Biskind), taking many liberties. The poor men and women at its fringes are trying to make any kind of life for themselves in America, stealing cattle from the wealthy just to survive. To hear men like capitalist Canton (Sam Waterson) talk about them, they're a cancer on his booming frontier civilization. He wants them dead.

Marshal Averil (Kris Kristofferson) becomes involved with the conflict. A former Harvard graduate whose commencement takes up much of the movie's first half hour, his heroic involvement in the frontier conflicts is mysterious. He seems to be putting on the role of adventurer. By the time of the movie's epilogue, he will be hanging out with New England WASPs again.

In the middle of Canton and Averil is Champion (Walken), who does the dirty work of keeping the county's immigrants in line, mostly through violence. If Walken's primary concern while acting is keeping himself amused, there's little that's funny in "Heaven's Gate."

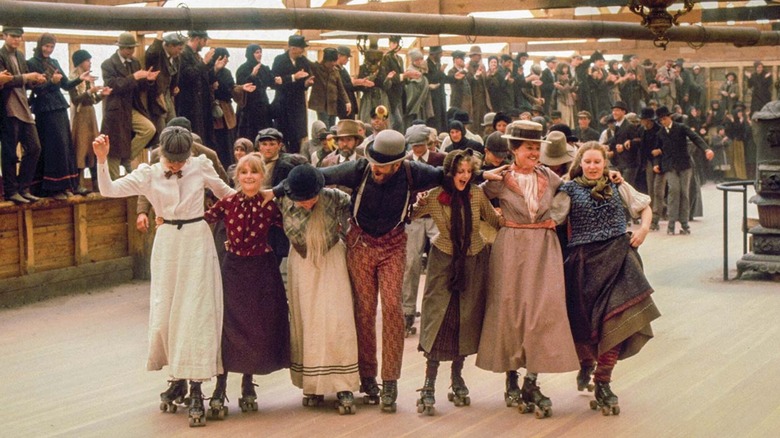

The film's story is thoughtful and grim, even in scenes like the protracted roller skating sequence (one scene that's iconic for the wrong reasons, looking out-of-touch and silly in a 19th-century Western). Difficult scenes of sexual assault and brutal slayings ensure the movie is appropriately depressing and uncommercial.

Making an epic

Being difficult and uncommercial would not have been the kiss of death for "Heaven's Gate" if it had won critical praise or awards. But it got nothing.

For some time, the movie was synonymous with a particular kind of Hollywood disaster: The overambitious, expensive, self-indulgent flop that was capable of practically killing a famous studio, United Artists. Peter Biskind, author of "Easy Riders, Raging Bulls," called the movie a "sorry end to New Hollywood," a cinematic movement throughout the 1970s that saw serious filmmakers taking advantage of the fractured studio system to make personal art. After "Heaven's Gate," those studios refused to let a "Heaven's Gate" happen. Never again would they pour that kind of money (a hefty $44 million in 1980 dollars) into a destined turkey.

Cimino was accused of dictatorial tendencies. Stories of his micromanaging perfectionism and wild expenses have been repeated since the movie's first week of production. Per Biskind, the director was shooting 30-plus takes per scene and going through $1 million a week. Speaking to Rolling Stone in 2016, Walken claimed "everyone was optimistic" during filming. He probably wasn't talking to the movie's producers, who saw the production spinning wildly out of control and sought in vain to steer it towards completion.

When the movie was finally released in November 1980, the New York premiere screening was so disastrous that Cimino and United Artists had to cut over an hour of its runtime before releasing it wide in April 1981. Walken, ever the movie's champion, told The Hollywood Reporter in 2020 that he walked out of that screening thinking he had "watched a good movie."

Reappraisals

Walken would only find his opinions vindicated over 30 years after the movie's release in 2012, when Michael Cimino was given the chance to recut "Heaven's Gate," bringing it closer to the version that screened at the catastrophic 1980 screening. It is, indeed, a "good movie."

"Heaven's Gate" is bold, muddy, and broken-hearted, a loose and rambling epic retelling of an obscure skirmish in late 19th-century U.S. frontier history. It deals with the unromantic details of human living that often get skipped over in history books, and it uses every second of its nearly four-hour runtime to help construct and deepen its sprawling drama.

The wealth of period detail in its production design is worth seeing as well. Walken, infamous for his tendency to steal something here or there from the sets on which he worked, would have had a field day. Walken told IndieWire that it "was always a beautiful movie to look at," impeccably designed and shot on location in Glacier Park, Wyoming, with enormous care by the great cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond.

As time passed, others who worked on the movie also admitted to having affection for it, showing that even if the film was designated a "disaster," it's worthy of admiration. In a conversation with the Financial Times promoting the movie's 2012 cut, Zsigmond called Cimino a "master painter." In that same article, Isabelle Huppert, who plays a madame named Ella in the movie, claimed to "love the film" as well. Walken is in good company.