Bassist Chris White reminisces on his rock career, Cher’s cover of a Zombies classic, more

By Catherine Frumerman

Christopher Taylor White hardly needs an introduction to Goldmine readers. Among his abundant accomplishments, he is The Zombies’ original recording bassist and the composer of many of their songs, including seven numbers on the iconic album Odessey and Oracle. Although he no longer tours or records with them, White is forever a part of The Zombies’ soul as the band perform several of his songs in concert.

GOLDMINE: Hello, Chris! So many good things are happening for you and for The Zombies. As we speak, The Zombies will have celebrated their 62nd anniversary with a long weekend of events called The First Annual Begin Here Festival in St Albans, England. Under grey, mid-November skies the festival saw the opening of a permanent Zombies display at the St. Albans Museum + Gallery, a stunning unplugged set by [vocalist] Colin Blunstone and [guitarist] Tom Toomey, and a screening of The Zombies documentary, Hung Up on a Dream, at the local cinema, which is appropriately designated The Odyssey. Knowing you, you must have thought it was hilarious that The Zombies would become a museum attraction. What was your first thought?

CHRIS WHITE: First of all, I’m still alive. And to be a museum exhibit is quite funny, to be honest. But I loved it. It’s the first time we’ve really been recognized in St. Albans, although we all went to school in St. Albans. I went ’round the corner where the museum is to the art college with [illustrator] Terry Quirk. So, I was at the art college when I joined The Zombies.

GM: The Blacksmiths Arms is seen as the cradle of The Zombies. But you didn’t even meet with [keyboardist] Rod Argent, Colin Blunstone, [guitarist] Paul Atkinson or [drummer] Hugh Grundy that day outside of this pub in April 1961. Outside, because they were too young to go inside! I assume first bassist Paul Arnold was there. Do you remember when you first did a rehearsal with the band? Strangely, you weren’t even introduced around. I think [bassist] Paul Arnold’s brother Terry just gave you the rehearsal’s address. So, you just showed up and played?

CW: That’s right. Well, I was at school with Paul Arnold’s brother. He was in the same year and class as me. He knew his brother was leaving the band and he knew I played in a small group. And so, he said would I be interested? So, I went down to a church hall St. Etheldreda in Hatfield and met them all and got on with them very well.

GM: But there was that story about how you would show up at rehearsal and Hugh Grundy didn’t know who you were.

CW: Well, Hugh at that time was going out I think with the dean’s daughter so every time we took a break at rehearsals he nipped out. He asked Colin several gigs later what my name was because he’d never really spoken to me till then. His love life was interfering with his playing. Simple as that.

GM: I think you saw the documentary Hung Up on a Dream a few times already. The latest edit is just under two hours, and I know there’s a lot more to The Zombies’ story — details that now exist only in memories.

My husband and I met a few people, while waiting in line, at the St. Albans Museum + Gallery where Jo Kendall from Prog magazine later interviewed you and Colin Blunstone and Hugh Grundy. Several people told us they had seen The Zombies perform at the Pioneer Club and the Ballito Hosiery Mill. One of the women told us that as a 12-year-old living across the street, she would go by Rod Argent’s house and ask his mum if he could come out to play. She remembers times when his mum said no since he was practicing piano. Peeking through the front window, the neighborhood girls would see him doing just that. Also, we met someone who was in The Vincents (named for the motorcycle brand) who also joined in the Herts Beat competition in 1964. But he couldn’t remember any details!

The Herts Beat competition, searching for the best upcoming beat-group in England, was where The Zombies beat out 99 other bands, won 250 pounds, and, separately, met someone from Decca Records, which resulted in the recording contract that gave us “She’s Not There.”

CW: When we won the contest we were approached by lots of dodgy managers wanting to manage us and there were no business lawyers or show business lawyers in England at that time that we knew of anyway. But my uncle Ted White was an arranger and was with a big band and worked for the BBC. So, my father said, “Let’s go and ask his advice.” And he said, “Well, I don’t know anything about recording, so why don’t you meet someone called Ken Jones who does records and produces?” So, we went along to meet [producer] Ken Jones and we all sat around and asked him. We gave him all the contracts and asked his advice and he read through each contract and said, “Well, that’s a good clause. That’s terrible, that’s terrible.” He went through all the contracts and then Colin or Rod, I can’t remember which one, said, “Can you do anything for us?” He said, “Yes, I’ll give you all the best clauses in the contract and we’ll do a production deal with Decca. You won’t sign with them, so we are control of the tapes.” He and [publisher] Joe Roncoroni were honest, we always got paid.

But then we had to have a manager and that was Tito Burns. He ripped us off about two million pounds. But that was standard for the day. People were just ripped off the whole time.

GM: Back to another memory, I can only wish I’d been a fly on the wall, a time-traveling fly with an iPhone, when Jimi Hendrix sang “Time of the Season” to you at the bar of Eric Burdon’s house in California. Would you tell us about that dreamlike moment?

CW: Oh, yes. Well, after The Zombies finished, Rod and I were producing, and we put Argent together and we were touring in America. We were playing one of the venues in Los Angeles and Eric Burdon was there and invited the band up to his house in Beverly Hills. He had a new group called War. I think it was the start of the group. And so, he had all the musicians in his garden outside. It was a lovely day and inside were lots of people as well. I sat at the bar in the house and Jimi Hendrix was sitting there and he said, “Oh, you were in The Zombies. I remember that song ‘Time of the Season.’” And he sang it acapella to me, just to me. No guitar, just him singing. And he was a lovely man, that was a great experience.

GM: How do you feel about Hung Up on a Dream, which I think director Robert Schwartzman called, “The most wistful psychedelic story ever told”?

CW: I was incredibly encouraged by the video and so was Rod. He wasn’t looking forward to it because he didn’t think there would be much stuff about us because we finished in ’68. We were only together really for three, four years. I don’t think there was anything else available. But I was quite impressed. And it was wonderful because Rod saw a film of his dad playing piano, which he’d never seen. They did some great research. They picked up loads of stuff, including my 21st birthday where we were playing.

GM: There was no sound on home videos back then. Do you remember what song that was?

CW: I showed it at a party and someone said it was the Isley Brothers’ “Twist and Shout.” We were all head shaking and everything.

GM: The Zombies very recently gained control of their 1960s catalog, acquiring it from Marquis Enterprises Ltd., to which you signed as teenagers in 1964. The new licensing company is aptly called Zombies Partners LLP, and it is owned by the four original Zombies and the estate of the late Paul Atkinson.

So, how does it work when someone like Cher, who just recorded “This Will Be Our Year” for her new Christmas album, wants to cover one of your songs. Are you personally involved? Can you say no?

CW: I could, but now that publishing has been sold to Wise. Carole Broughton who was secretary at Marquis bought the company off Ken [Jones] and Joe [Roncoroni], who’ve since died, obviously. She sold the publishing side to Wise [Music Group]. We still retain the rights of the stuff we did in the ‘60s. That’s just the recording rights and they’re separate from the publishing rights. So, I could stop Cher singing my song, but I wouldn’t want to! I think ‘Yes, please’ comes into it more likely!

GM: Were you surprised by Cher recording your song?

CW: Yes. I didn’t know anything about it until your email that Cher had recorded this “This Will Be Our Year,” which, of course, has become the perennial wedding song. I’ve played it at two of my sons’ weddings and it’s lovely to have someone else record it. It’s wonderful. Cher did a great version.

(Note: “This Will Be Our Year” wasn’t Cher’s first cover of a White song. Sonny and Cher also recorded White’s 1964 song “Leave Me Be.” White recalls producer Ken Jones saying, "Cher’s got more balls than Sonny.")

GM: Do you have a favorite cover of any of your songs?

CW: Everybody does it differently and I just love them all, to be quite honest. It’s so nice to hear someone singing a song.

GM: Would you tell us how your song “Hold Your Head Up” came about?

CW: What happened is we were sharing a flat at that time. Rod lived in one room, Terry Quirk lived in another room. And, basically, we wrote things by ourselves and then we played it to each other. I had practically written all of “Hold Your Head Up” when I was living in Spain with my first wife when she was pregnant with our first son, who’s now 51. She was having a rough time. It was a hope song. Rod liked it and his contribution was the arrangement and the big solo in the middle. And of course, when we finished Odessey and Oracle, Rod and I started our own production company. He’d had two hits in America by that time, but he said to me one day, “Look, why don’t we put our joint names on all the songs we write because one song will keep us going.” So that was very generous of him. Then the first song we wrote together was “Hold Your Head Up.”

GM: You’re up to Volume Six – The Production Sessions of The Chris White Experience CD series. There are some outstanding songs on each disc. Volume Six includes “High Windows” where Colin Blunstone sings lead. This song was considered for The Zombies’ album New World. And “Ghosts,” which is very haunting (pardon the pun). There’s beautiful piano on “Ghosts” from Rod Argent. Moreover, there’s an interesting story about how the writer of the song, Brian Cullman, found his perfect guitarist. He was standing on a movie line with his girlfriend. And when they got to the ticket office, they heard music from a boombox and it turned out to be Mark Knopfler before he became famous.

CW: Oh, yes, it was. This was just after I’d done demos for Dire Straits. I’ve also got a song which they haven’t released yet. I’ve still got the tapes. The manager denies it exists.

Brian Cullman asked me, because Rod was busy with Argent, to produce his demos. He came over from New York. He said, “I love this guitarist called Mark Knopfler.” I’d already met Mark Knopfler because I was asked to do the Dire Straits original demos. I did it for free. The idea was that if I got a deal for them, I would produce it. But that didn’t happen. Story of my life, basically. But Mark later said, “Oh, I listened to the demos we did the other day.” He said, “It’s much better than the final album we did. You should have got the job.” So, I said, thanks very much, Mark. Yeah.

I’d forgotten that my wife and I, when we moved out of our flat, put loads of tapes into my mother-in-law’s attic. When we took them out, we found about 800 unreleased tapes of songs I’ve been working on the past 50 years. And then Jamie and Matthew [White’s sons who founded their own label, Sunfish] gave up their jobs and are working putting out all these CDs of stuff that was never released. They’re up to six at the moment, and they’re just working on a Record Store Day vinyl as well, which is a selection from those CDs. They like to make sure everybody gets credited and paid.

GM: Also, there is an attention-grabbing bass, a bass-y twang, on “Ghosts.”

CW: It’s Dill Katz. He was just so good.

Matthew worked at studios and did some time at Abbey Road himself when he was younger. Because the one thing I said, years ago, whatever you do, don’t go into the music business or go out with actresses. And they both ignored it. Jamie then had his own band [Et Tu Brucé, who opened for The Zombies tour many years ago in America], but he was doing accounting and working for advertising companies. And then both of them got together and decided to put these CDs out, which I totally encouraged. So, they gave up their day jobs. There’s at least another three CDs coming out.

GM: How do you write a song? Is it with the intention that you’re going to sit down at the keyboard and write? Or does inspiration hit at odd times, and you find you’re leaving little notes to yourself around the house?

CW: Absolutely correct. Yeah. I used to keep a notebook in my pocket, but I keep losing that and keep losing bits of paper. I remember Mark Knopfler always said he used to listen to conversations that were going on and someone would say something. And then I met another writer when I was living in Spain, and he said he gets ideas from American magazines like Time magazine, chapter headings or paragraph headings, and they suddenly spark something off in your mind. So, sometimes it happens with just a thing you’ve read in the newspaper, something someone says, or a drum rhythm, or you hear a chord and that starts going, but I have no idea where it comes from. It’s in the ether. And sometimes you write a song and find somebody else has written a similar song at the same time. Ideas are flowing around in the ether, I think, basically.

You can’t tell what’s going to happen because I’ve written lyrics for other people’s music and I’ve written music for other people’s lyrics, so it’s just the song, it happens to you and sometimes it’s unbelievably fast, but normally it takes time to get it right. I like to work very hard on it.

GM: Do you work on a keyboard?

CW: Yes. Well, nowadays you can record patterns and I’ve got a keyboard right here. When we first recorded, it was only on four tracks in Abbey Road, so Odessey and Oracle was done on a four track. As you probably know, we went in as The Beatles finished Sgt. Pepper’s. The Beatles got fed up with just four tracks. And in America they had some eight track machines, but it wasn’t in England, so they got the engineers there, like Geoff Emerick and Peter Vince, to link two four tracks together. So, we recorded drums, bass and guitar on one track, keyboards on one track, lead vocal on the third one and then anything else on the fourth one and then we just had to bounce it down to another four track. At the time we were only asked to mix in mono, you see. So, we finished the mono, we only had 1,000 pounds to do the whole album, and then they said, “Oh, look, stereo is very interesting, so can you now mix it in stereo?” Which was a ridiculous thing because it was all mostly on mono tracks, so we just had to spread it out.

It’s quite true that we rehearsed very thoroughly to get the songs right because we only had the 1,000 pounds to do the whole album. So, we went in having rehearsed in village halls and different places. We knew the songs inside out. But then we walked in and when we saw John Lennon’s Mellotron, Rod’s eyes lit up. There were no synthesizers in those days. So, Rod jumped on it so he could have strings, flutes and all sorts of things. And that was all because of The Beatles.

It was like a keyboard, really and what it was, the Mellotron, in those days was just loads of tapes up the back and you played a note, it came up, then it sprung back down again, so you only had a few seconds on each note. Nowadays it’s all electronic, of course, but in those days it was manual, and it broke down quite often.

GM: Your early career objective was to be a visual artist and teach art. When did you realize you can write good songs? Was “You Make Me Feel Good,” which was on the B-side of The Zombies’ first single “She’s Not There,” the first complete song you wrote?

CW: I’d written some rubbish when I was playing in small groups and skiffle groups, and I’d written probably one more song, but I never recorded it. The first song I wrote was for our first recording sessions, “You Made Me Feel Good,” because Ken Jones said to us, “Well, you can always write something.” As most people know nowadays Rod came up with “She’s Not There.” And I wrote “You Make Me Feel Good.” And Rod, to this day, thinks it should have been the second single rather than the B-side. But in those days, you just use what you have.

GM: At the time The Zombies recorded these two songs, there was a question of which one would be the A-side on that first venture. How did you decide that it would be “She’s Not There”?

CW: We didn’t decide. It was the producer decided, but it was a difficult decision.

GM: On most of the songs in the growing Chris White Experience CD series you were acting in the role of producer, not performer. How have you found this to be creatively different from being a songwriter performer?

CW: No, it’s all involved with the songwriting and then you do those things and people like what you’ve done with the production and then it’s ‘would you like to produce this album?’ So that’s what’s happened most of my life, really. And production isn’t much different from songwriting, except songwriting is, when it’s successful, worth more money. You can afford to live then.

GM: Was there a song or two where your input as producer changed the direction or structure of the piece from what the composer performer brought to you at first?

CW: Yeah, I did an album with American singer called Michael Fennelly, who had a group called Crabby Appleton, and he came over to London to record an album with me. And I got on with him very well and have met with him since. He had one lovely song on there and I said it sounded like those New Orleans dirge songs, funeral things. It wasn’t a sad song, but I got some musicians I knew to come in, brass players, and they totally changed his arrangement. And that’s the main thing I remember because I love that song.

GM: Who were your early musical influences? Did you come from a musical family?

CW: We all came from working-class backgrounds. My father was a London bus inspector and then he left them after an argument and opened a shop in Markyate. So, he was a shopkeeper, but he played upright bass, double bass in bands and things. And my Uncle Ted was a sax player, and he did the big band arranging and everything. My sister played piano. I played guitar, first of all, because it was rock and roll.

Then he suggested I start learning to play the bass, so he started teaching me the bass. Then I discovered [electric] bass guitar with rock and roll. And it was much easier to carry around. My father used to carry a double bass on the back of his little, tiny car. Then I learned how to put a double bass into a mini later through the side door and then the fretboard sticking out the front window side door. So, yeah, it was quite an experience playing upright double bass and electric guitar. And then, of course, my father, he had a grocery store and furniture store. When we started getting equipment, we bought things on the never-never, as we called it here. He advanced us some money to buy amplifiers, microphones and things like that. We paid him back from the gigs, which wasn’t much money. As Colin says, we used to get six quid a night between us five. Five of it went to the equipment and the rest was just our bus fares.

GM: Did you have to get on a bus with a double bass ever?

CW: No, I bought somebody’s homemade bass, which ended up in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. (In Cleveland.)

GM: The last time I saw you perform with The Zombies was March 2019 at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony in New York City. Do you think you’ll ever be onstage with the rest of the band or record with The Zombies again?

CW: I will struggle on a few days if I’m asked to. But of course, traveling now I’m 80, the insurance doesn’t cover me. And Rod and Colin are going to find that soon as well because they’re approaching 79, 80. I would go up onstage, but I’d have to practice before I did it. I remember when Rod and Colin were thinking of us coming up to do a couple of numbers from Odessey and Oracle, and I said to Hugh Grundy, I think we should rehearse for that. So, every weekend I got together with Hugh and we ran over the Odessey and Oracle tracks. And we were well rehearsed when we met up with Rod and Colin and they couldn’t remember a thing! We knew the songs better than they did. But you have to work, you have to exercise and do proper stuff.

The nice thing is we’re still friends. Which great rarity for a ’60s band, to be quite honest, of those who still of us who are still alive. But we’ve toured with lots of people who don’t even stay in the same hotels. They don’t speak to each other outside of being onstage. But we started as friends and school kids, basically, so we got that bond, and we grew up and learned our trade together, which is a rarity.

It could happen. Yeah, I would definitely consider it because it’s great. When we were touring in America in the last 10 years, I looked across the line of people onstage and they looked 25 not in their seventies. And that’s the fun of being onstage. And the feedback from the audience is most marvelous thing of all. It energizes you.

When I was living near Barcelona an Irish musician said to me, “We’re going to see this fella called Bruce Springsteen.” I said, oh no. I’d heard about, you know, I’ve seen the future of rock and roll and it’s Bruce Springsteen. I said no. I don’t think I want to go. And he, Francie Conway, talked me into going. And the sum result was I stood up for three hours and lost my voice because I was so excited. It energized me totally. And then when we went down to see the documentary in Texas (The Zombies’ documentary, Hung Up on a Dream, at the South By Southwest Festival), Rod and his group played and I had the same feeling, the same excitement. So, I was really energized by that as well.

GM: What about recording again with The Zombies? A formal recording? Would you ever do that?

CW: I don’t think that’s going to be in the cards because Rod has a great group ‘round him now.

GM: Your dear friend Terry Quirk, who is famous for painting the Odessey and Oracle cover, died in 2020. You were working with him on a musical about The Zombies up until that time. Have you done more work on it?

CW: No, I tried a few things, but other things have taken over — the CDs and other work and things, and I’m not sure which way to go at the moment, though I’ve had lots of people interested in it. It’s a matter of money and putting a musical on is very expensive. I know Tim Rice very well, and he’ll tell you that because he’s lost so much money on things. I haven’t got the energy at the moment because I’m working on so many other things, but I still like it. I still think the idea of telling the story about us in the Philippines (Which was a near disaster: Contracted to play the second largest arena in the world for ten nights, the band were kept under lock and key and accompanied by armed guards if they ever went out, in order to protect the concert promoter’s investment. Moreover, the band ended up paid pennies.) and how Odessey and Oracle came out of it. It’s a good story, I think, but you need a lot of backing and a lot of money. And, of course, COVID finished a lot of theater things and musicians. So, let’s hope for the future. I’ve got 10 years at least! It’s the joy of creating, and the energy, really. It’s difficult, but you have to keep trying things.

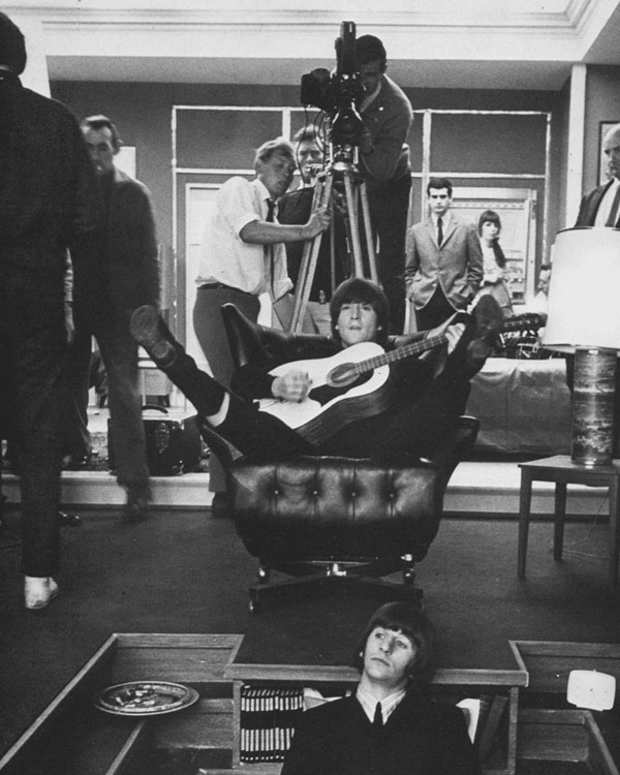

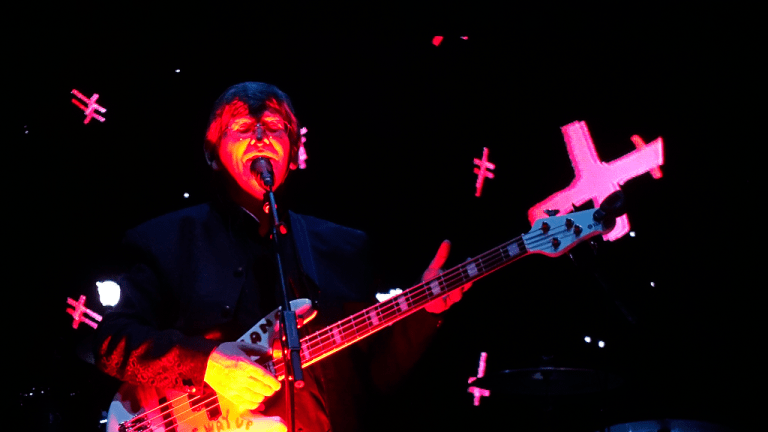

Rod Argent, Hugh Grundy, Chris White and Colin Blunstone of The Zombies (original band members on Odessey and Oracle tour) -

Photo © by Bruce Frumerman

GM: Are you mentoring any younger bands right now?

CW: The only one is Jamie and his writing and his band. He still writes songs and puts stuff in the studio. He’s having an album coming up soon on Sunfish Music. I’m getting old to mentor groups because it’s a young generation thing. New things. They’ve got to find their own way.

I’d encourage them to work with people they were brought up with. It’s not always easy, but nevertheless, he’s got a small cachet of people he works with who aren’t working musicians but do it in their spare time. And he just likes creating.

Who was it? Dave Grohl. Yeah, he said, “You should go into a garage and suck.” Basically, just mess around, just enjoy yourselves and feel the passion.

GM: Bonus question — Rod Argent quotes Shakespeare on the back of Odessey and Oracle, and Colin Blunstone was lead singer for a one-album band named Keats. Later you helped found a Zombies project and recorded an album in order to save the band’s name from imposters who were stealing it. The title track is called “New World (My America),” borrowed from the English metaphysical poet John Donne. Was that your way of giving tribute to, perhaps, your favorite poet? And can you tell us how Donne has influenced you? And have we seen him elsewhere in your songs?

CW: I loved his poetry because it was very sensual. And “New World” came from a poem, which was called “To His Mistress Going to Bed.” He wrote, “Oh, my America, my new-found land.” It’s just full of sensual images. And of course, then he became a bishop, didn’t he? Later he tended to disown his sexual poetry. But he’s a lovely writer. [The influence of] the images and the poetry and the rhythms sink into your mind and it comes out another way. I mean, we all borrow things from things we’ve heard and it just comes out a different way. It’s not copying or plagiarism. It’s just exciting you in a different way.

GM: Is there something else you’d like to add for your fans; for aspiring musicians?

CW: I’d like to thank the fans because I’m still here after 55 years or 60 years, I can’t remember. Basically, we have gone through a hell of a journey and we’re still friends. Young writers, as I said before, should keep on writing because it’s creative and it’s energizing. So, it’s very important to keep writing or creating things. It’s what we need in the world, especially in this time when it’s all destructive. So, yeah, just keep working on creative things and different ideas. Whatever the form, keep writing music.