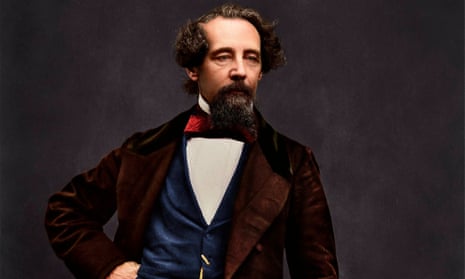

The novels are unlike any other writer’s. People have likened them to poems, to visions, to pantomime, and they are all these things. If you want to see how different he was to all his contemporaries, just try to imagine George Eliot or Thackeray or the Brontë sisters doing those reading tours, when thousands of people, the poor in multitudes, came to hear him. Nothing like it had been seen since John Wesley’s preaching tours.

There have been thousands of books on Dickens. I wanted, nevertheless, in The Mystery of Charles Dickens to set down some of my lifelong obsession with his work. One thing I wanted to winkle out, if I could, was the relationship between the life and the work. Something much more complicated was going on than with most novelists, all of whom take versions of their own lives and turn them into fiction. At a much deeper level than most, Dickens was confronting his own demons – the wretched childhood, the appalling relations with women – and turning them into melodrama, tragedy, farce, burlesque. That sense we all flickeringly retain of our childhood self watching the behaviour of the baffling and often scary grownups – that sense in him was hyper-developed, and it is what turbocharged the books.

1. Selected Journalism 1850-1870 (edited by David Pascoe)

It might seem paradoxical to start my list with the journalism, but Dickens began as a journalist and he never stopped being one. While pursuing a life as a prolific novelist, tireless charity worker, fairly frequent actor, Dickens kept up weekly journalism, and edited two of his own periodicals, Household Words and All the Year Round. Try reading A Nightly Scene in London from 1856, in which Dickens takes us to Whitechapel, where he finds five bundles of old rags thrown down by the walls of the workhouse. The bundles turn out to be women, of course. One of his strongest pieces. Or read Lying Awake, the justly famous account of the joint public hanging of the Mannings, a married pair of murderers.

2. Sketches By Boz

Again, journalism, but journalism morphing into the fiction. He took the name Boz from his brother Augustus’s nickname. Published the year before Victoria became queen, and written when he was in his early 20s, it is so vivid, so warm, so comic, so passionate. London Recreations, whose title is self-explanatory, is not merely descriptive. It contains that hatred of busybodydom and evangelical humbug that burst out in a more mature essay for Household Words, The Great Baby – the baby being the public, patronised by Those Who Know Best.

3. American Notes

A better account of the young Dickens’s take on the US than the one novel I’d deem a failure, Martin Chuzzlewit. He visited America’s prisons, saw its great landscapes, appreciated its hospitality and open-heartedness. But he could not stick the evangelical Christianity. “Wherever religion is resorted to, as a strong drink, and as an escape from the dull monotonous round of home, those of its ministers who pepper the highest will be surest to please. They who strew the Eternal Path with the greatest amount of brimstone, and who most ruthlessly tread down the flowers and leaves that grow by the wayside, will be voted the most righteous”.

4. A Christmas Carol

In many ways this, the most famous of all his books, is his best. Christmas was central to his world-vision that simply trying to be a little kinder to one another both as individuals and as a society might be an experiment worth trying. If, reading these words, you have never tried a book by Dickens, I’d recommend starting with the famous story of how Scrooge was converted from a belief in money and power into someone who saw the power of love. The fact that it is set in the form of a fairytale is a good preparation for the longer fiction all of which, at its most successful, possesses some of the power of such stories.

5. David Copperfield

His own personal favourite among the novels. A book that can make me – and millions of others – weep and laugh out loud, often on the same page. A sort of autobiography, but one in which all his family have been expunged. David’s father is dead before the book begins, his mother dies when he is still very young. And unlike Dickens, David has no siblings. The awful woes and cruelties for which in real life he blamed his parents are the fault of the wicked stepfather Mr Murdstone. This book has some of Dickens’s finest characters – Mr Dick, Mr Micawber, Betsey Trotwood – and, in the storm that engulfs the Suffolk coast, one of his most powerful descriptions of nature.

6. Great Expectations

If Copperfield was a rather benign version of his autobiography, here he takes the gloves off. The person he is beating up is himself. Pip believes he has inherited wealth from the sinister Miss Havisham, the rich woman of Rochester, whereas in fact the source of his wealth is the convict, Magwitch, to whom as a child Pip had shown kindness. The mistake which Pip finds so shattering reveals, to him and to us, all his skewed values, all his cult of wealth and status. Technically the most flawless of the fictions, and one that makes for truly uncomfortable reading.

7. Little Dorrit

In Copperfield, Dickens’s improvident father was depicted in the benign, comical figure of Mr Micawber, whose spells in the debtors’ gaol are a kind of joke. In Little Dorrit, the actual experience of Mr Dickens senior in the Marshalsea prison fed into one the most powerful of all his mature works. Equally terrible, presumably because it was unconscious on Dickens’s part, is his expression of profound mother-hatred in the figure of Mrs Clennam, the power-mad businesswoman exercising control from the darkened sick-room of her tottering house. An amazing masterpiece.

8. Bleak House

Another great masterpiece. One of the things that overpowered me, as I reread and reread Dickens in preparation for my book, was how he confronted and analysed the sheer beastliness of the 19th century. In this book, famously, he satirised the slow, corrupt processes of the law and the high court of Chancery, but really, when you read of the death of Little Jo the Crossing Sweeper or listen to the slow drip-drip-drip of boredom and rain at the aristocrat’s house, or work out the tangles of the plot through the life and death of society solicitor Mr Tulkinghorn, you realise that it is the 19th century itself on trial, swathed, like London in November, in fogs of cruelty .

9. The Old Curiosity Shop

A relatively early one, and very like a fairytale or a panto. It contains some of his most vivid characters, not least Mr Quilp, a furious, crazy self-projection, which tells you much more about Dickens than does the rather vapid self-portrait in Copperfield. Quilp’s cruelty to his wife is, we now realise, all too true a portrait of his own behaviour as a husband to his harmless wife. The relationship between Little Nell and her gambling-addict grandfather, and their attempt to escape Quilp, leads us on a journey out of London, with vivid landscape and cityscape pictures of the nightmare that was Victorian England. One of his best.

10. The Mystery of Edwin Drood

In the book he did not live to finish, he returns to the Rochester of his boyhood. It seems to be very VERY different from the others, not least because, as far as we can judge from remarks he made to friends and family, he intended to end it with a monologue by a convicted murderer who had committed his crime while under the influence of opium. But there are many theories about who killed Edwin Drood, or, indeed, whether he was killed. The book shows signs of Dickens’s weak health, and some of the chapters are as dead as anything he wrote. But there is a flare of genius, like the glory of sunset, in the pages he penned.

The Mystery of Charles Dickens by AN Wilson is published by Atlantic Books. To order a copy, go to guardianbookshop.com.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion