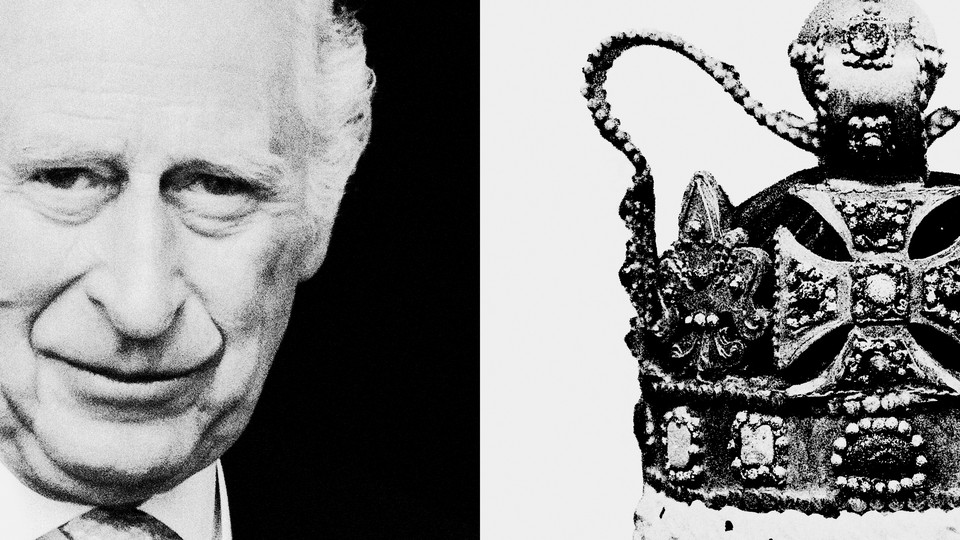

King Charles’s Very Hobbity Coronation

What the new monarch’s investiture will reveal about his character—and Britain’s

It has been 70 years since the world last witnessed the crowning of a new British monarch. On Tuesday, May 2, The Atlantic’s editor in chief, Jeffrey Goldberg, joined the U.K.-based staff writers Sophie Gilbert and Helen Lewis to talk about the new era of the monarchy and its role both within the United Kingdom and on the international stage. Watch the full event here.

One of the stranger aspects of the modern British monarchy is that its special occasions come with an official dish. Where his mother had curried chicken for her coronation, an exotic proposition in 1950s Britain, King Charles III now has a ceremonial quiche. The recipe, according to Buckingham Palace, involves “a crisp, light pastry case and delicate flavours of spinach, broad beans and fresh tarragon.” The quiche is simple to make, can be easily adapted for those with allergies, and—much like the Royal Family’s ongoing revenge on Prince Harry—is a dish best served cold.

I hesitate to read too much into a quiche, but you could argue that the “popular oven-baked savoury tart” (thank you, The Times) is a symbol of the new King’s political outlook. Charles’s worldview is hard to describe, because it blends eco-radicalism with deep traditionalism. He has been talking about green issues since the 1970s—he was way ahead of the curve on organic farming—but his environmentalism is very different from the leftist doomer vibes of Extinction Rebellion or Just Stop Oil. Instead, it springs from an aristocratic sense of merely passing through the world, of being a custodian for the next generation. The Royal Family loves sustainability, as you might too, if you’d inherited all your sofas. A free tip to anyone lucky enough to be among the 2,000 guests who will be inside Westminster Abbey for the coronation: Don’t wear Shein. As of a few years ago, the new King was still wearing a pair of shoes he bought in 1971.

Last year, when Queen Elizabeth II died, my former colleague Tom McTague referred to her son and heir as the Hobbit King: “He is far more interested in the benefits of traditional English hedgerows than the great, global glory of Britain.” How right he was. The invitation to the coronation on May 6 is illustrated with a hedgerow border, complete with a bee, a wren, and a garland of oak leaves. It even features a Green Man, a quasi-mystical symbol of rebirth carved into many English churches. (Sadly, the new King declined to include a carving often paired with the Green Man, the Sheela Na Gig, a female figure “showing pink,” as they say in the porn industry.)

Whenever I write about the British royals, I find myself wondering how a family that owes its position to the illegitimate son of a Norman noble invading Sussex in 1066 can credibly claim to be at the vanguard of social change. The gold coronation coach will trundle through crowds of onlookers squeezed by inflation of up to 80 percent on basic foodstuffs in the past year. Royal visits to the Caribbean are now marked by intense awkwardness over the legacy of slavery and colonialism. And as Meghan Markle discovered sometime between her 2019 Vogue guest-edit and her escape to British Columbia the following year, duchesses are poorly placed to talk about equality.

Nevertheless, King Charles is trying, in his hobbity way, to move with the times. At the coronation, the oil used to anoint him will be vegan-friendly—something that caused consternation among certain tabloids—because it will not be made with ambergris or civet musk (extracted, respectively, from whale intestines and a tree mammal’s anal glands). But family tradition comes into play too: The oil will come from olives harvested from beside the grave of Charles’s grandmother Alice, in Jerusalem. It has been blessed by an Orthodox patriarch with a huge beard.

These attempts to reconcile old and new are everywhere in the ceremony. The oil might be free from feline anal musk, but as with his mother’s coronation in 1953, Charles has decided not to allow cameras to film the anointing—which he considers to be a moment of connection with God. At the same time, he has previously defined himself as a “defender of faiths” as well as “defender of the faith.” (The latter title was conferred on Henry VIII by the Pope in 1521, in one of history’s most spectacular “you’ll never guess what happened next” moments.) The coronation will be overseen by the Anglican archbishop of Canterbury, but also attended by Britain’s chief rabbi, who has been given a room at a royal residence within walking distance of the Abbey so he doesn’t have to use a car on the Sabbath; the Catholic archbishop of Westminster; and London Mayor Sadiq Khan, a Muslim. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, who is Hindu, will read from the New Testament. Not everyone likes these attempts to bring the coronation into the 21st century. One particularly overwrought article in The European Conservative accused Charles of having a “Koraonation” because of his sympathy for Islam, while in The Telegraph, Petronella Wyatt offered my single favorite paragraph on the whole hoopla: “It is particularly disturbing that the Earl of Derby has not been asked to provide falcons, as his family have done since the 16th Century. These little things deprive people of their purpose in life.”

The case against Charles will be well known to anyone who’s watched The Crown; read Prince Harry’s memoir, Spare; or picked up a supermarket tabloid in the past half century. He was cold to his first wife, distant to his second son, and his brother was a friend of Jeffrey Epstein. He used to have an aide to squeeze his toothpaste onto the brush—an aide who later had to resign from Charles’s pet charity after promising to obtain an official honor for a Saudi tycoon in exchange for £1.5 million. Nonetheless, it’s quite funny that the descendant of nearly 1,000 years of mildly inbred aristocrats is less frothingly anti-woke than the average Fox News talking head. To the new King’s credit, Buckingham Palace officially supports academic efforts to research the family’s links to the slave trade, and Charles attended the ceremony in 2021 where the new republic of Barbados formally dispensed with his mother’s services as head of state.

For all his undoubted faults, Charles has recognized something about the British character—that we find change most palatable when we’re wallowing in nostalgia. You can see it in the Brexit vote, which was presented to Baby Boomers less as a leap into the unknown than a reversion to the status quo ante—specifically the early 1970s, before Britain joined the Common Market, a time within living memory. In a similar vein, one of the BBC’s lockdown hits was a show called The Repair Shop, filmed at a historic museum where visitors can see what medieval British houses were like (I’ve been to the museum, so I can tell you: cold, damp, and faintly redolent of pigs). The program, hosted by the furniture restorer Jay Blades, attracts Britons desperate to have their heirlooms revived. If you like the sound of someone spending several hours carefully beating out the dents in a vintage fireman’s helmet, Repair Shop is for you. Last year, the series featured one Charles Windsor promoting the Prince’s Trust vocational-training initiative, in which young people learn how to become blacksmiths and stonemasons.

Blades, a Black Briton who comes from inner London and has a gold tooth, bonded with the Windsor heir, who carried a handkerchief that could have doubled as a bedsheet, over their love of traditional crafts. “The great tragedy is the lack of vocational education in schools; not everybody is designed for the academic,” said Charles, who attended Cambridge University despite performing terribly on his secondary-school exams. “Not me,” agreed Blades, who discovered as an adult that he was functionally illiterate. The moment showed that the new King is desperate to give middle Britain what it loves: the aspiration to judge people not by the color of their skin, but by their ability to restore a 19th-century commemorative tea set.

Which brings us back to the quiche. It was specially designed to be shareable, with the hope that patriotic Britons will host coronation street parties at which it can star as the eggy focal point, the savory showstopper, the shortcrust pièce de résistance. I’m tempted to laugh at that idea, but it’s barely been six months since thousands of people lined up for 12 hours straight to see Elizabeth II lying in state. The anti-shoplifting gates at my local supermarket are now decked with purple banners urging me to celebrate her son’s ascent to the throne. My local park is holding a “South London samba” festival. You can buy a coronation-themed illuminated cushion.

Britain is a strange and unfathomable place, even to those of us who have been here all our lives. I want to tell Americans that we are nothing like Downton Abbey and The Great British Bake Off, and then I remember that our new King has an official quiche.