“You deserve a longer letter than this, but it is my unhappy fate seldom to treat people so well as they deserve…” – Jane Austen

Introduction:

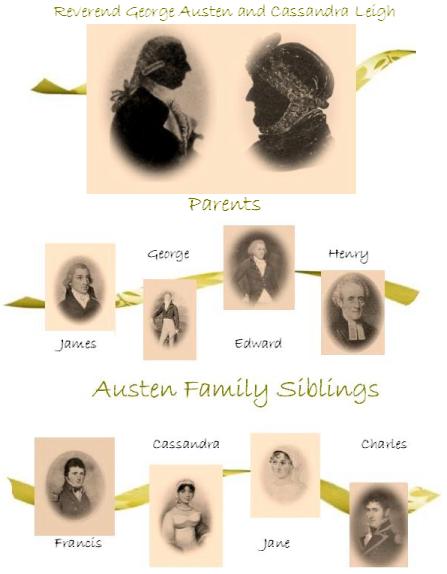

In August, 1798, Rev George and Mrs. Austen and their daughters Cassandra and Jane visited Godmersham, Edward Austen-Knight’s estate near Godmersham, Kent, where he had moved with his family in November, 1797. While Jane and her parents returned to Steventon in October, Cassandra remained behind until March, 1799. Jane wrote the following letter on Christmas eve in the middle of Cassandra’s prolonged visit.

Godmersham Park, 1799, Wikipedia public domain image

Jane Austen’s letter:

Steventon: Monday Night, Dec 24 [1798]

My dear Cassandra

Our ball was very thin, but by no means unpleasant. There were thirty-one people, and only eleven ladies out of the number, and but five single women in the room. Of the gentlemen present you may have some idea from the list of my partners—Mr. Wood, G. Lefroy, Rice, a Mr. Butcher (belonging to the Temples, a sailor and not of the 11th Light Dragoons). Mr. Temple (not the horrid one of all). Mr. Wm Orde (cousin to the Kingsclere man). Mr. John Harwood, and Mr. Calland, who appeared as usual with his hat in his hand, and stood every now and then behind Catherine and me to be talked to and abused for not dancing. We teased him, however, into it at last. I was very glad to see him again after so long a separation…

There were twenty dances, and I danced them all, and without any fatigue…My black cap was openly admired by Mrs. Lefroy, and secretly I imagine by everybody else in the room…Of my charities to the poor since I came home you shall have a faithful account. I have given a pair of worsted stockings to Mary Hutchins, Dame Kew, Mary Steevens, and Dame Staples: a shift to Hannah Staples, and a shawl to Betty Dawkins: amounting in all to about half a guinea…

I was to have dined at Deane today, but the weather is so cold that I am not sorry to be kept at home by the appearance of snow. We are to have company to dinner on Friday: the three Digweeds and James. We shall be a nice silent party. I suppose.

You deserve a longer letter than this, but it is my unhappy fate seldom to treat people so well as they deserve…God bless you!

Yours affectionately, Jane Austen

Steventon Parsonage, Wikimedia Commons

This short letter might reveal very little information to the contemporary reader, but Cassandra knew the context of every sentence Jane wrote. She knew the people, time, place, and setting, since she lived it. No detailed descriptions were needed for Cassandra to comprehend the letter’s full meaning

Thankfully for us, records and books exist that will help us make more sense of Jane’s cryptic words.

The Years Leading to Austen’s Letter

Jane and Cassandra had just experienced a number of eventful years. In 1796, Jane met and danced with Tom LeFroy at Deane. We know the details of this meeting in the first existing letter Jane wrote to Cassandra. In August, 1797, Cassandra learned that Thomas Fowle, her fiance, died tragically of fever in the West Indies months earlier and was buried at sea. A little over a year after the shocking news, she must still have been in deep mourning.

By 1798, Jane had already written the first drafts of Pride and Prejudice, initially entitled First Impressions, and Sense and Sensibility, originally drafted as an epistolary novel entitled Elinor and Marianne. Just five months previously, her dear cousin Lady Williams (Jane Cooper) had died in a carriage accident, another cause for mourning.

Timeline of events:

| 1795 | (?) | Cassandra engaged to Thomas Fowle. |

| May | Mrs. James Austen died. | |

| 1795 | -6 | Mr. Tom Lefroy at Ashe. |

| 1796 | First Impressions (Pride and Prejudice) begun. | |

| 1797, | Jan. | James Austen married Mary Lloyd. |

| Feb. | Thomas Fowle died of fever in the W. Indies. | |

| Nov. | Jane, with mother and sister, went to Bath. | |

| First Impressions refused by Cadell. | ||

| Sense and Sensibility (already sketched in Elinor and Marianne) begun. | ||

| 1798, | Aug. | Lady Williams (Jane Cooper) killed in a carriage accident. |

| Mrs. Knight gave up Godmersham to the Edward Austens. Jane’s first visit there. | ||

| 1798, | Aug. | First draft of Northanger Abbey begun. |

About Austen’s Letters

Deidre Le Faye in Jane Austen’s Letters, 4th Edition, listed Austen’s known letters in chronological order. At a glance one can see when and where the sisters were apart. Many casual readers think of Jane as a spinster and a homebody, but the list demonstrates how often and how extensively she and Casssandra traveled, largely in the south of England. This link leads to an interactive map of her travels in Smithsonian Magazine.

Le Faye chronicles the ten letters Jane sent to Cassandra during her visit to Godmersham. They were written from October 24, 1798 to January 23, 1799. This letter, which described past and future events, was dated December 24th, Christmas eve. The ball had already occurred. Christmas festivities in 1798 were rather simple compared to festivities introduced during Queen Victoria’s time, (Click on this link to a Georgian Christmas). Jane must have missed her sister even more on this occasion.

Deirdre Le Faye, in her descriptive article for Persuasion #14, 1992, entitled Jane Austen’s Letters, described the letters as “often hasty and elliptical–the equivalent of chatty telephone conversations between the sisters, keeping each other informed of the events at home…interspersed with news of the day, both local and national.” (p. 82, Jane Austen’s Letters)

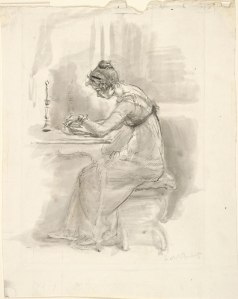

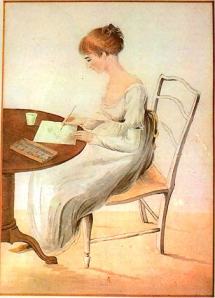

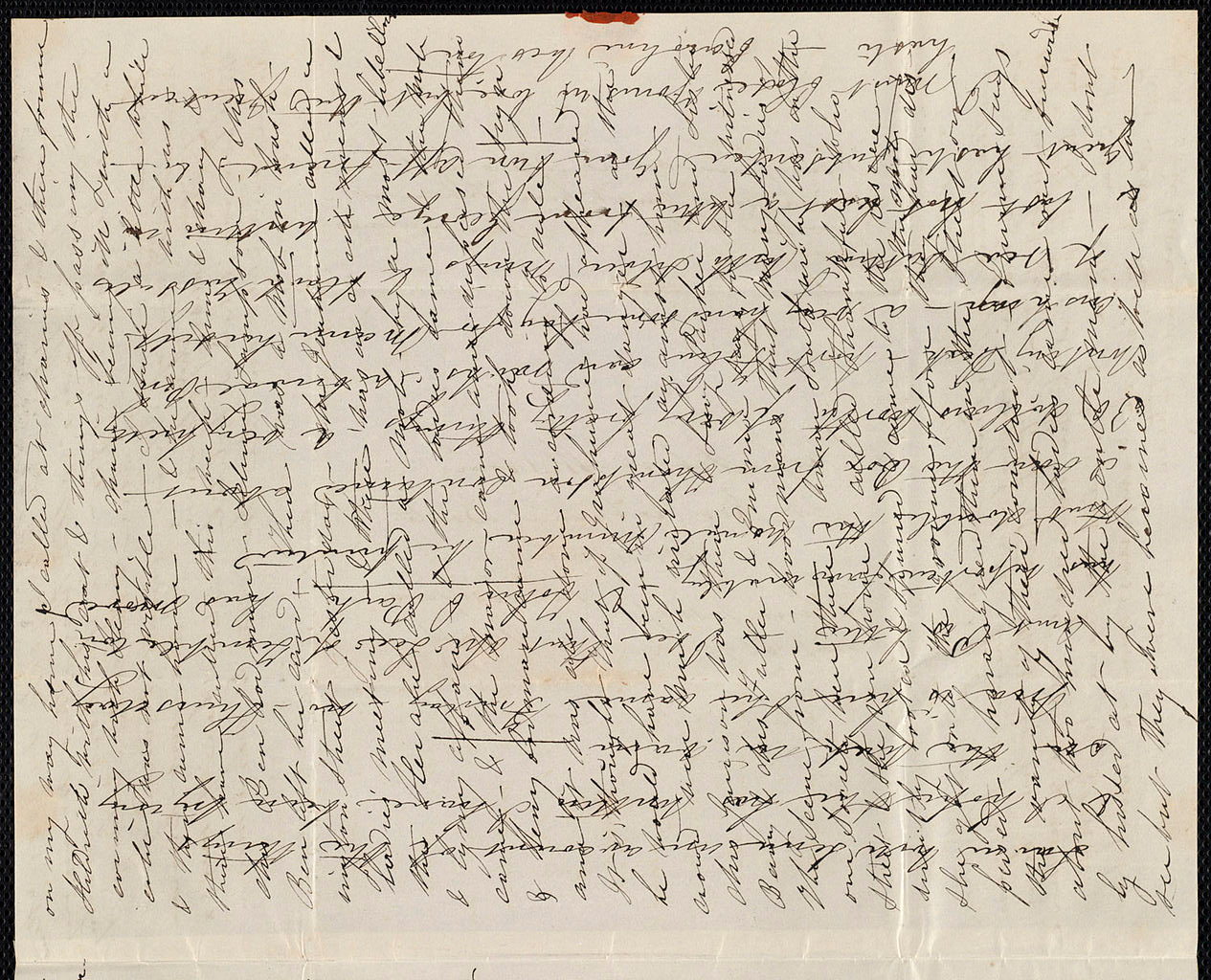

Example of a cross written letter to save paper and postage, much as the Austens sent to each other. The recipient of the letter paid for the postage. Paper was saved by cross writing. Image in the public domain.

When Jane and Cassandra were apart, they wrote each other every three days, or five letters in a fortnight. As soon as one was sent, they began to write the next one. The letters followed a pattern, telling the other of the journey, then about daily events and how life was at home, then talking about the visit at the destination, and finally of the journey home. This pattern helped Le Faye determine which letters (or set of letters) were missing or destroyed by Cassandra.

When Jane was ready to mail her letter, Mr. Austen dropped it off at the post box in Deane as he made his rounds throughout his parish. Cassandra bequeathed this letter to Fanny Knatchbull, née Austen-Knight, which eventually made its way into her son’s, Lord Brabourne’s, publication of Jane’s letters.

Events in the Letter: The Ball, the People, and the Setting

The setting

In her December 24th letter, Jane indicated her physical fitness – she danced all twenty dances without any fatigue. As a country girl who helped her family in the kitchen garden or with breakfast, and who walked into town, to church, or to visit neighbors at Deane or Ashe, she was in prime physical condition. View this map of Steventon, Deane, and Ashe.

She described the ball as being thin.

“There were thirty-one people, and only eleven ladies out of the number, and but five single women in the room.“

It is hard to tell if the ball was public or private. The word “thin,” however, indicated that it must have been public to anyone who had a subscription. If the ball had been private, then the hosts would have ensured that the correct number of persons of both sexes would have been invited. Once they accepted the invitation, good manners would have obliged them to show up. If the December ball had been private, Jane would surely have known who and how many were coming. There would have been few surprises.

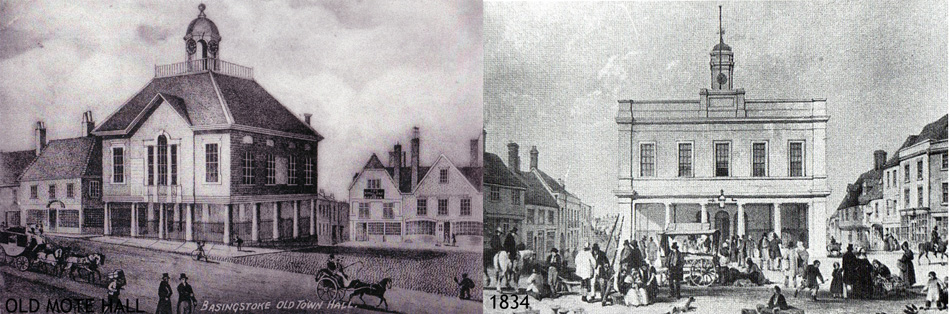

Basingstoke Town Hall in the late 18th early 19th centuries.

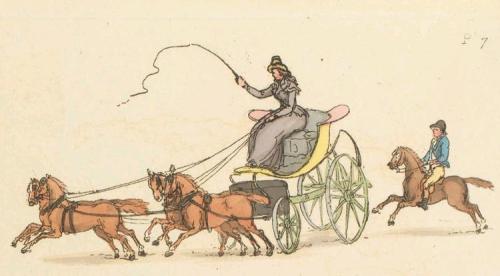

Public assembly balls were held in Basingstoke’s town hall, which was a little over 7 miles from Steventon (an hour’s carriage ride in good weather, since horses pulling carriages traveled 6 miles per hour on average). Dancing was performed in a ballroom on the first floor that also held a card room for gentlemen like Mr. Austen, who might not have felt like dancing.

“Frequent allusions are made in the “Letters” to the county balls at Basingstoke. These took place, it seems, once a month on a Thursday during the season. They were held in the Assembly Rooms, and were frequented by all the well-to-do families of the out-lying neighbourhood; many of them, like the Austens, coming from long distances, undeterred by the dangers of dark winter nights, lampless lanes, and stormy weather.” – Jane Austen: Her Homes & Her Friends, Constance Hill, Illustrations by Ellen G. Hill, John Lane, The Bodley Head Limited, first Published 1901. Downloaded August 30, 2020.

The people

Dancers Jane described in her letter were:

Rev George and Mrs Anne Lefroy (née Brydges). The reverend obtained his living in Ashe in 1783, and Madam Lefroy, as she was locally known, was Jane’s good friend and mentor. In her letters, Jane talked of visiting friends and neighbors, such as the Lefroys of Ashe Park, which was within easy walking distance. In 1800, Jane wrote:

“We had a very pleasant day on Monday at Ashe (Park). We sat down fourteen to dinner in the study, the dining-room being not habitable from the storms having blown…down its chimney. There was a whist and a casino table…” – Constance Hill

Ashe Rectory. Illustration by Ellen Hill

Mr. Wood: All we know about John Wood is that he was Jane’s dance partner.

Rice is most likely Henry Rice, who married Jemima-Lucy Lefroy. He was known to be a fun-loving spendthrift who was often bailed out by his mother.

Mr. Temple, mostly likely Frank, who served in the navy. His friend was Samuel Butcher.

Mr. Butcher (belonging to the Temples, a sailor and not of the 11th Light Dragoons.) Samuel Butcher was five years older than Jane. He was appointed to HMS Sans Pareil in 1795.

Mr. Wm Orde (cousin to the Kingscler man) of Nunnykirk “perhaps.” He remained unmarried.

Mr. Calland, who Penelope Hughes-Hallett identified as the Rector of Bentworth. The joke in the Austen family was that he always appeared at any function with a hat in his hand, which Mrs. Austen made fun of with a poem. On this day, Jane and her friend Catherine teased him into dancing.

Catherine is Catherine Bigg, daughter of Mr. Bigg Wither of Manydown Park, and Jane’s good friend.

“Manydown is within easy reach of Basingstoke, and Jane often stayed there when the Assembly balls took place. She had done so on the present occasion.”- Constance Hill

18th century engraving of Manydown Park

Of my charities to the poor…

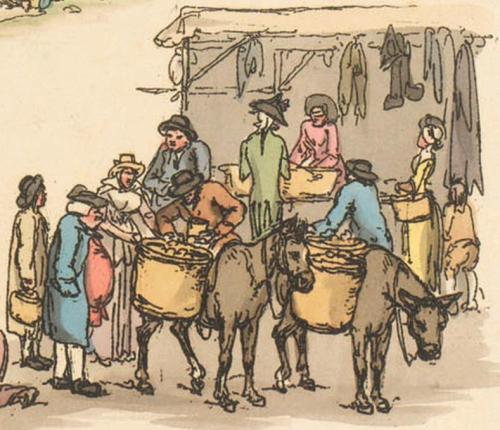

In this section of the letter, Jane listed the Steventon villagers who received her largesse:

“ I have given a pair of worsted stockings to Mary Hutchins, Dame Kew, Mary Steevens, and Dame Staples: a shift to Hannah Staples, and a shawl to Betty Dawkins:”

Hannah was Dame Staples’ daughter. Jane Austen, as a rector’s daughter of the most influential man (not the richest) in the parishes he served, was obligated to support the many poor ladies in Steventon. Her gifts, simple as they seemed, were multiplied by the gifts of food and clothing from the community at large and kept the villager women from dire extremes. Mrs. and Miss Bates in Emma depend on the kindness of neighbors to survive, as Jane wrote in scene after scene.

The Austens, while influential in Steventon, were not rich. They belonged, as Lucy Worsley writes in Jane Austen at Home, to the pseudo-gentry.

“Jane belonged to the pseudo-gentry; there was land in her family, but her parents and siblings didn’t own land, so they had to make do and mend and gloss things over.”

Pseudo-gentry kept up appearances even though their means fell short of their richer neighbors, friends, and relatives. Still, Jane managed from her meager yearly-pin money of around £20 to spend a sum “amounting in all to about half a guinea….”

Half a guinea was a gold coin minted from the Guinea Coast in Africa, which ceased to be minted around the time of this letter. The idea that Jane possessed a gold coin is far fetched. In Austen’s day, a guinea had a value of 21 shillings–this value could change depending on the quality of the coinage in use. Interestingly, the gold coin’s purchasing power (comparing Austen’s time to now), remains a little over 1 pound today. (CPI Inflation calendar).

The ball and dances

“Balls in the days of Miss Austen consisted mainly of country dances, for the stately minuet was going out of vogue, while the rapid waltz had not yet come in. We must picture to ourselves the ladies and gentlemen ranged in two long rows facing one another, whilst the couples at the extreme ends danced down the set; the most important lady present having been privileged to “call” or lead off the dance.”… Constance Hill

Which dances did Jane Austen dance?

Country dances as late as 1798 had very little variation, with long lines of couples progressing up and down a set that could last from twenty minutes to as much as an hour. This and other dances mentioned by Austen included cotillions performed as a square by four couples. The boulanger was known as a “finishing” dance performed at the last. It was physically an easy dance to do and one that after a night of physical exertion was probably most welcome. – (“What did Jane Austen Dance,” Capering & Kickery, 2009)

Dances Austen might have danced in 1798, since they were popular during that time, were the Scotch reel, the minuet (rapidly going out of fashion), and Sir Roger de Coverley, another finishing dance (although no record exists of Jane mentioning this dance). One dance she and her contemporaries decidedly did not dance during this period was the waltz, although Jane might have heard its music. (Capering & Kickery.)

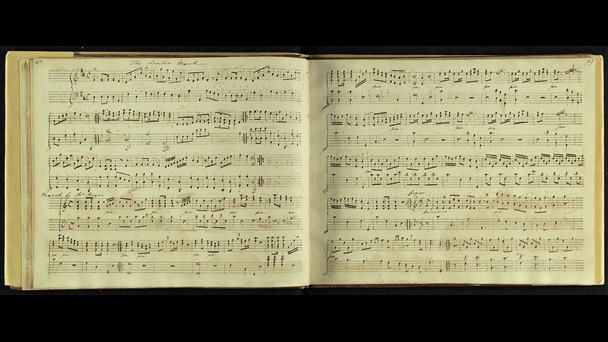

The Music

Jane adored music and she made eight volumes of her own collections, two of which she wrote by hand (copying sheets of music). The music included songs by Handel and English composers, and instrumental pieces by Correlli, Gluck and J.C. Bach. (Jane Austen and classical music: how Bath brought them together, Discover Music.)

‘The London March’, manuscript music copied by Jane Austen, image in the public domain

Susan of Capering and Kickery reminds readers that dancers during the end of the 18th century and in the Regency era paid attention to fashionable “music in the moment.” Dancers would not have chosen to dance to music popular in the 17th or early 18th centuries. “Austen was no more likely to dance a 75- or 100-year old dance than she was to wear fashions from a hundred years earlier.”

Many contemporary comments regarding the music in the recent mini-series of “Sanditon” and the film, “Emma.” 2020, were scathing regarding the raw country tunes that were played in the dance scenes, many of which were Scottish airs and folk music, like “The Water is Wide,” which is popular to this day. Yet these movies have it wrong.

“… dances like “Hole in the Wall,” “Mr. Beveridge’s Maggot,” “Childgrove,” and “Grimstock” (all dating from 1650 to 1710) are nothing Jane Austen or her characters would have been caught dead dancing.”- Capering and Kickery

Yet, due to films, such as 1995’s “Pride and Prejudice” (an adaptation I admire), modern audiences accept these dance choices as authentic. Neither Cassandra nor Jane would have.

The Musicians

Well-paid musicians in London would have played more sophisticated pieces from the Continent interspersed with popular English music. Country balls, however, employed traveling musicians (from 5-6) who sought work from town to town. Villagers and townsmen might have sought out local talent, who consisted of anyone who could play an instrument, no matter the quality of their play. Think of Mary Bennet, whose talent at the piano forte was bad, versus an impresario like Jane Fairfax. Elizabeth Bennet could play tolerably well and Anne Elliot was called upon to play at the piano forte as the family rolled up the carpet for an impromptu dance in the evening.

Henry Raeburn, violinist and composer, 1727-1807

Ball dress:

The only reference Austen makes to her dress is:

“My black cap was openly admired by Mrs. Lefroy, and secretly I imagine by everybody else in the room…”

At twenty-three years of age, Jane was almost on the shelf and in danger of becoming a spinster. She had begun to wear caps earlier than most other unmarried ladies, and in this respect her quote was not surprising. It is hard, however, to find a black cap in the fashion magazines of her day and before. Black hats were shown in the magazines, but not caps in that color. They were generally made of white muslin and sewn by the women who wore them. Tom Fowle’s death hit Cassandra hard (she was not to learn of his passing until months after the event when the ship made it back to port.)

Cassandra knew exactly what Jane was writing about regarding the cap; but we can only conjecture. Regency mourning customs were not as strict as in Victorian times, but wearing a black cap was perhaps Jane’s way of honoring his memory and perhaps Jane Cooper. The following quote from The British Library states:

“The Gallery of Fashion shows a lot of mourning dresses. A woman might spend a considerable part of her life wearing mourning of some sort, for distant relatives as well as close ones, so it is not surprising that there was a pressure to remain fashionable while doing so.” – Gallery of Fashion, The British Library.

In any case, little is known of the black cap. The closeup of this image is the only 1798 full dress example I found online after hours of searching.

Detail, Fashion Plate, ‘Full Dress for Dec. 1798’ for ‘Lady’s Monthly Museum’

In 1798, ladies’ dresses made the transition from round gowns (so prettily drawn in Nicholas Heideloff’s Gallery of Fashion (1794-1802) to sleeker, more figure hugging gowns popular in the early 19th century.

Fashion Plate, ‘Full Dress for Decr. 1798’ for ‘Lady’s Monthly Museum’, LACMA (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

Women’s dresses during this decade sported trains. Austen’s gown in the ball she attended in 1798 was probably a full dress gown, since the senior Austens were too often strapped for income to afford a full array of morning gowns, walking gowns, dinner gowns, full dress gowns, and ball gowns for their two girls.

Jane began to write Northanger Abbey in 1798, when gowns with trains were fashionable. This extra fabric must have gotten quite dirty during country walks and work around the house, and might have tripped the dancer and her partners if left to its own devices. This passage from her novel provided the solution:

“The progress of the friendship between Catherine and Isabella was quick as its beginning had been warm, and they passed so rapidly through every gradation of increasing tenderness that there was shortly no fresh proof of it to be given to their friends or themselves. They called each other by their Christian name, were always arm in arm when they walked, pinned up each other’s train for the dance, and were not to be divided in the set;” – Chapter 5, Northanger Abbey

“Pinned up each others trains”, Northanger Abbey illustration in the public domain, Hugh Thompson. British Library.

Shoes and the accoutrements of a lady’s dance wardrobe

Interestingly, many shoes made for dancing lasted for only one evening or two. The slippers, constructed of cloth or delicate kid, barely lasted the full hours of physical exertion. The slippers were festooned with rosettes made with a fabric that matched or complimented the ladies’ gowns. Mrs. Austen made dance slippers of fabric for her grandchildren, much in this tradition.

Gloves not only came above the elbow, but were often made of kid leather, which were a buttery color. The gloves also were made with white or an assortment of pale, soft colored cloths. Gentlemen wore gloves as well, for it was unseemly for a gentleman and lady to touch each other with bare hands. Another necessity, especially on warm nights, or when candlelight and exertion overheated the ballroom, was a fan.

Dance cards were not yet as popular as in the 19th century, but a lady knew not to commit to too many dances ahead of the ball in case a likely prospect entered the room later in the evening. A couple could dance only two sets together, for dancing more than two was considered ill-mannered.

As mentioned in this letter, only five single women danced in a room with twenty men, which meant that each female was quite busy and exhausted at the end of the night. After supper, served around midnight, the ladies and their partner sat with the lady’s family or chaperones. The etiquette of the ballroom was quite strict. Once a lady refused to dance with a gentleman, she had to sit out the rest of the dances for the evening.

In her novels, Jane used this convention to differentiate the villains from the obedient or the heroes and heroines, or to demonstrate personality quirks. Mr. Elton’s rudeness in refusing a dance with poor Harriet Smith in Emma humiliated the young woman and spoke ill of his character. Mr. Knightley, in inviting Harriet to dance, showed his heroic instincts. These actions demonstrated a gentleman’s quality better than any exposition Jane could have written. Her contemporary readers knew this, but we in the 21st century must learn these quirks of etiquette through research and reading.

Post Ball mentions

“I was to have dined at Deane today, but the weather is so cold that I am not sorry to be kept at home by the appearance of snow. We are to have company to dinner on Friday: the three Digweeds and James. We shall be a nice silent party. I suppose.”

Image of Deane House, Ellen Hill.

Dining at Deane meant dining in the old manor house of Deane with Squire Harwood and his family. In this house Jane had danced with Tom Lefroy in 1796. The Harwoods were very well off according to late 18th century standards, but this was not to last. Upon his death in 1813, it was discovered that John Harwood had mortgaged his estate to the hilt, leaving his heir in ruin and his widow and daughter with nothing.

As for not dining with the Harwoods in December, 1798, the narrow country lanes between Steventon, Deane and Ashe were filled with deep ruts. Wet snow would have deterred the company from visiting their good friends.

Austen’s letter ends with a planned dinner with the Digweeds on Friday, December 28th. The Digweeds were tenants of Steventon Manor in Steventon Parish, who rented the land from Mr. Knight in Godmersham Park. (p. 18, Jane Austen’s Country Life.) The Digweeds and the Austens grazed hundreds of sheep around the village. (p. 21, Country Life.) Harry and William-Francis Digweed (who, with their brothers, were playmates with the Austen siblings) were joint tenants until 1798. James Digweed, ordained in 1797, became curate of Steventon in 1798. Jane, it seems, anticipated a quiet (boring?) evening.

Gentle reader: This analysis ends my research into this letter, which was sent shorthand to Cassandra. She would have mentally filled in the gaps easily and fluently, gaps that we today struggle to understand.

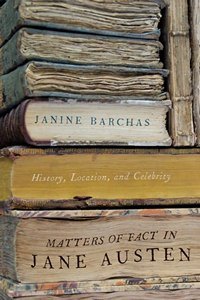

Deirdre Le Fay, who passed away just a few weeks ago, painstakingly researched Austen’s letters and their corresponding information for her massive undertaking, Jane Austen’s Letters, 4th edition. With its lists of letters, the letters, abbreviations and citations, notes and general notes on the letters, select bibliography, biographical index, topographical index, subject index, and general index is 667 pages long. This world has lost a scholar of the first rank.

References:

Jane Austen’s Letters, Deirdre Le Faye, Oxford University Press, 4th Edition (December 1, 2011), ISBN-10 : 0199576076, ISBN-13 : 978-0199576074

Jane Austen’s Country Life: Uncovering the rural backdrop to her life, her letters and her novels, Deidre Le Faye, Frances Lincoln (June 1, 2014) ISBN-10 : 0711231583, ISBN-13 : 978-0711231580

Jane Austen at Home: A Biography, Lucy Worsley, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 2017. Hardcover, 400 pages. ISBN-13 : 978-1250131607, ISBN-10 : 125013160X

A Dance With Jane Austen: How a Novelist and her Characters went to the Ball, Susannah Fullerton, Frances Lincoln, 2012. ISBN-10 : 0711232458, ISBN-13 : 978-0711232457

“Historian Lucy Worsley goes around the houses with Jane Austen at York Literature Festival,” By Charles Hutchinson, The Press, 19th March 2018: Downloaded 8/25/2020, https://www.yorkpress.co.uk/news/16097178.historian-lucy-worsley-goes-around-houses-jane-austen-york-literature-festival/

A Visitor’s Guide to Jane Austen’s England, Sue Wilkes, https://visitjaneaustensengland.blogspot.com/2015/07/down-on-farm.html

“The Three Churches of Steventon, Ashe, and Deane.” Downloaded 8-29-2020: https://www.alltrails.com/trail/england/hampshire/the-three-churches-of-steventon-ashe-and-deane?u=i

“Steventon, Basingstoke, Deane survey,” downloaded 8-29-2020: https://getoutside.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/local/steventon-basingstoke-and-deane

Shoe roses: downloaded August 30, 2020. https://janeausten.co.uk/blogs/fashion-to-make/make-shoe-roses “No aunt, no officers, no news could be sought after; — the very shoe-roses for Netherfield were got by proxy.”–P&P Netherfield Ball

“What Did Jane Austen Dance?” Capering & Kickery, Nov 1, 2009: Downloaded Aug 30, 2020. https://www.kickery.com/2009/11/what-did-jane-austen-dance.html