James Taylor

The singer-songwriter genre was named around 1970, give or take, and was said to apply to me and, among others Joni Mitchell, Cat Stevens and Jackson Browne. Why that supposed movement didn’t begin with Bob Dylan or even Woody Guthrie or Robert Johnson beats me – maybe they were still “folk”. But, if it means anything, Carole King deserves to be thought of as its epitome. I’d been deep into her songs – Up on the Roof, Natural Woman, Crying in the Rain – for a decade before Danny Kortchmar introduced us in Los Angeles in 1970. She played piano on my Sweet Baby James album while working on the songs for her own Tapestry. Our collaboration, our extended musical conversation over the next three or four years was really something wonderful. I’ve said it before, but Carole and I found we spoke the same language. Not just that we were both musicians but as if we shared a common ear, a parallel musical/emotional path. And we brought this out in one another, I believe.

It was a big change for Carole to leave New York for LA. She left behind an established, hugely successful career as a Brill Building [era] tunesmith, with her husband and lyricist, Gerry Goffin, and went west, on her own, with two young daughters. She started writing by herself, about herself – that is to say, from her own life. It came out of her so strong, so fierce and fresh. So clearly in her own voice. And yet, so immediately accessible, so familiar: you knew these songs already. I had that experience the first time I heard Carole sing You’ve Got a Friend from the stage of the Troubadour: “Oh yeah, that one.” Incredible that this song didn’t always exist. Carole’s focus was her family: [children] Louise and Sherry, and imminently, Levi and Molly. She had no time for the stuff the rest of us in Laurel Canyon were up to. She had her family and her songs. Certainly she would have her adventures, dramatic emotional switchbacks, in years to come. But in those days, she seemed to watch the dancers with a kind, wry detachment. To me, she was a port in the storm, a good and serious person with an astonishing gift, and, of course, a friend.

Roberta Flack

I first heard the Shirelles’ version of Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow when I was working as a school teacher in Washington DC. The song stuck with me – I included it in my repertoire at [pub] Mr Henry’s on Capitol Hill and later recorded it for my album Quiet Fire. It was for me a time of deep introspection and this song expressed a vulnerability that each of us experiences in the course of finding and embracing love. Donny [Hathaway] and I loved the songs on Tapestry and worked out our arrangement of You’ve Got a Friend in a way that expressed how we felt about what it means to help each other through the best and the worst of times. My friend and fellow Aquarian Carole King has shaped our musical landscape with the songs that she wrote that touch each of us in such deeply personal ways.

Tori Amos

In 1971, a cool teenage babysitter put the new album Tapestry on the stereo, and, at seven years old, my mind was blown. It was almost as if Mother Earth herself was singing to us. There was a clarity to the storytelling, whether the songs had us dancing with them or haunting us as we sat cross-legged on the worn Methodist rug. And after we had laughed and cried during the playing of the album, we were both very sure that in Carole King we had both found a new friend for life.

MC Taylor, Hiss Golden Messenger

They don’t make records like Carole King’s Tapestry any more. They can’t, because I don’t think the people who might attempt to do so have ever totally reckoned with the kind of magic she was working on that album. Consequently, the types of records that Tapestry made it possible to make and sell in large numbers – records that are vulnerable, confessional, sung and played by the person who wrote the songs and “classic” in sound and sentiment – often feel emotionally supercharged, where Tapestry feels plain-spoken and easy. As someone who makes music that shares at least some kind of DNA with King’s iconic album, I can attest that making a record as compelling as Tapestry requires the mastery of a language that Carole King invented. It’s sort of a musical Rosetta stone, and a huge testament to what an incredible interpreter of the human experience she was, and continues to be.

Rickie Lee Jones

I first heard of Carole King when I was about 16. James Taylor brought her to the attention of the wider world when he asked her to open for him in 1971. But the truth is I had been listening to her most of my life, through the voices of the many women and men who recorded her music.

Up on the Roof, recorded by the Drifters, never grew old on my record player. I didn’t have to live in the city to understand how much it meant to have a place to call your own, to feel how hard life is after working all day and looking up at the stars and finding a smile in your heart. Carole and Gerry delivered a Valentine that day, one the whole world opened year after year. The sum of the song was greater than the words themselves: “Hustling crowd”, “tired and beat”, “right smack dab” – phrases that could become dated, but never did because the sentiment was so kind. Somewhere in there are the seeds that blow all the way to New Jersey, and plant themselves into young Bruce Springsteen who, like me and Chuck E and Junior Lee, invited Wendy, Kitty, and all the others Up on the Roof. It was the safest place a kid standing in the shadow of city life could find, on top of the world listening to the stars.

Folk rock had long dominated the FM airwaves when music began to make a move back to the fundamentals of songwriting: the three-minute song, the chorus sung thrice, the bridge – an endangered passage from one end of the song to the other. I was happy to hear songs again coming from Cat Stevens, James Taylor and Carole King. She wrote from a genre she had been part of creating, the rock’n’roll of soul.

Tapestry was the most important record of its time. I won’t qualify it by saying female, songwriter or any of that. It signalled the country and the people’s desire to have a simple and beautiful song to sing. With Carole King, matters of personality and the adoration of the star are set aside. She is first a working woman. Her hit You’ve Got a Friend was written for Gerry, who had mental illness, to let him know that even though she may not be by his side, she was always on his side. I know nothing about the two of them except this: they wrote great songs, and the culture that I call mine is shaped in part by the music they wrote while Carole was still just a kid.

Tapestry’s success roots us to our musical history. It overcame whatever current trend would render it passé and continues to sell year after year. That woman on the cover of Tapestry evoked a calm and peaceful soul. I used to just sit and stare at it. She looked like an educated woman who took care of her life. Fifty years later, Tapestry remains undaunted and timeless as it is reflected in the voices of women who discover the songs as if they were just written last year. Easy enough to remember, haunting enough to want to remember, that is the mark of a great song – and great songwriter.

Randy Newman

I think you could make a pretty good case that Carole King and Gerry Goffin were the best popular songwriters of the last half of the 20th century. I love Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow. Everything she sings is deeply felt.

Sharon Van Etten

Tapestry was one of the first records my mother and I bonded over. It was so meaningful to sing in unison with my mom to a guttural, honest account performed by a stranger to whom I felt so inexplicably connected: a friend, a sister, a mother, and somebody’s daughter, a low voice and an attitude. From that point onward, I carried her music and spirit with me.

I reconnected with King’s music when I was in high school. I was about to audition for choir. I always leaned toward rock in the classical world. The three songs on my list to audition with were: You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away by the Beatles and I Feel the Earth Move and Natural Woman by Carole King. I narrowed it down to the two Carole King songs and was given the choice of show choir or madrigals.

Carole’s songs made me want to sing her melodies and her harmonies and I felt closer to her while finding my path as a singer even at that young age. In my 30s, watching her musical on Broadway, I was overwhelmed with feelings of gratitude for her story. It showed the way in which a woman can pursue her own career, have a family and achieve happiness. That is a delicate balance that I strive for in my own life every day.

Joan Armatrading

One of the best albums, ever, by one of the best songwriters, ever. Period.

Devendra Banhart

The cover of Tapestry has the same welcoming atmosphere of the record. It’s this musician saying: “Here I am. I’m not wearing a bunch of makeup. This is my home. I wrote these songs, and I’m not perfect.” It was the opposite of what was being sold at that time. She’d written a lot of hits for other people, but the message of Tapestry is that once you drop the artifice and be yourself, that’s when the voice rings true.

I got into the album as a teenager in California where I was longing for a bygone era that only existed in record covers: the Doors at the Whiskey-a-Go-Go or whatever. Tapestry is a very California-sounding record and has something of that Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young getting-back-to-nature side, but without any of the theatrics. The landscape is internal, not external. It has themes of self-discovery. She’s also the master of sentimentality, nostalgia and homesickness but delivered without any syrup. She has a crystal-clear voice, and a way of expressing perfect longing and melancholy like no one else.

Lucinda Williams

I would have just turned 18 when Tapestry came out, when I was really being influenced by singers and songwriters. Carole King was an inspiration. She was a woman, and she wrote amazing songs – so you’d learn by listening to It’s Too Late or whatever, over and over. She set the stage for other singer-songwriters who came along after her, because there wasn’t a market yet and the industry didn’t know what to do with us.

None of us singer-songwriters were known for our voices, and we had to get past that. I had to get past the fact that I wasn’t going to sound like Linda Ronstadt or Joni Mitchell or Carole King, but from Carole I learned that you can accept your own voice and work within your limitations, which was liberating.

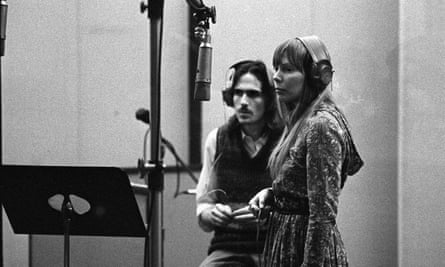

Danielle Haim

When my sisters and I were growing up, Tapestry was a key record in the house. Our mum also loved James Taylor and Joni Mitchell, who played and sang on it, so it was on in the car a lot. Our mum was from Philly on the east coast, so it was always in my mind that Carole was also a Jewish east-coast girl. She’d write these amazing, emotive songs and sing them in an almost optimistic or carefree voice.

Once she left the songwriting world and started writing for herself, it got less straightforward and more personal. So Far Away is really complex. The bridge is just insane. I’ve heard that song so many times, but a few weeks ago it came on the radio when I was driving, and I was totally stunned.

When you write a song it’s almost mystical. It feels as if the words just come out and it can be months or even years later you realise: “That’s what was happening.” I’d love to know who those songs are about. I think female artists are great at just letting it all show. As artists, my sisters and I feel like having Carole always in our lives definitely inspired us.

Margo Price

Tapestry is exactly that: a sonic tapestry of some of the greatest songwriting and a masterclass in blending the roots of folk, soul, rock and blues while never feeling forced. My father told me about the album when I was about 18, and it shook me to the core. It became one of the blueprints that I measured smart pop music by. Many have tried to imitate Carole’s sound, and great artists like Aretha Franklin have interpreted her work because her songs are timeless, limitless and, in a way, defy genre. This album has been one of my constants during quarantine. Even in its saddest moments, Carole’s voice can lift my spirits and move mountains.

Natalie Merchant

It is a shock to admit that I could have been cognisant of an event that occurred 50 years ago, but my summer of 1971 memories are quite vivid. I was just seven, but I could feel the seismic changes of the times: they were shaking the foundations of my home. The earth was moving under my feet and the sky was tumbling down. My parents’ marriage was in pieces – my mother had thrown it against the kitchen wall in an effort to shatter the mould of her postwar, Catholic-American girl-self. She got a job, she wasn’t home when we came back from school, she didn’t drag us to mass on Sundays any more, she stopped wearing a bra, and she stopped loving our father.

Her new friends were young single women. They drank red wine and communed deep into the night over the ecstasies and sorrows of their unattached, sexually liberated, self-actualised lives. They idolised Gloria Steinem, read Susan Sontag and dressed like Jane Fonda. And without exception, they all listened to the ladies of the canyon, that trinity of confessional singer-songwriters: Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon and Carole King.

To say Tapestry was part of the soundtrack of my childhood would be a woeful understatement. It was a speckless mirror where we girls and women saw ourselves reflected: natural, beautiful, powerful, fragile, lonely, joyous, regretful and resolute. It was a handful of songs and simple contradictions that were all truths. It was a brimful cup of intoxicating freedom, and it was the souring aftertaste of all that headiness. It was realising the price of striking out alone was growing weary of the world and craving the same ties that had made us feel so bound-up.

A skilled craftswoman, Ms King wrought something durable with Tapestry that has not outworn its usefulness. Her 12 songs have been ringing clear and true for 50 years. We all understand when she mourns constancy and asks: “Doesn’t anybody stay in one place any more?” We know how people shift, how they change, how they go away, and oftentimes leave us longing. When “something inside has died”, or we are “down and troubled” and turn to music for shelter and consolation, we will always find it in this album.

Rufus Wainwright

Tapestry was around our house when I was growing up, but I connected with it more when I moved to California because it’s the blueprint for anybody who’s starting off in songwriting in LA. Carole King made this incredible transformation from Brill Building songwriter to performer, but she didn’t go crazy or self-destruct. She was able to remain a good parent and – especially now I’m a father – she has always been a role model for me.

Tapestry is a bundle of emotions, and she doesn’t sound like anybody else. She wasn’t necessarily the greatest singer, but she has a unique style and attack. She’s not pulling any punches: it’s a great lesson in how to be yourself and be successful. She’d worked with great songwriters and artists, and knew all the great recording engineers and session players, and was able to channel everything she’d learned in her own way. Tapestry is the ultimate in terms of doing what you want artistically and just surviving as a human being in the record business. She made this amazing milestone in music without having to sacrifice her soul to do it.

Natalie Mering, Weyes Blood

Tapestry is part of the American songbook. I heard those songs even before I knew who she was. I love that book Girls Like Us, a trio of biographies of Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon and Carole King and the story behind Tapestry. The record before it [1970’s Writer] hadn’t performed that well, so she had it in her head that this one had to be great. She was meditating a lot. She was probably in some mental-spiritual prime, and then when she realised what fame entailed she was like: “No way.” She cared more about her personal life.

Even though she made Tapestry in LA, she’s very New York. It’s witty and spicy. I can relate to her musical sensibility – being classically trained like I was, but writing pop songs and singing these very deep things. Tapestry is as good a meeting point as you get between popular and some sort of underground feel. She was really living all that hippy stuff – vegetarianism, hippy skirts – and I think that’s why it resonated. She’s the nice motherly side of it. You can imagine her making you a sandwich after the crazy hippies stole your stuff.

Stephin Merritt, the Magnetic Fields

The radical thing about Tapestry is its refusal to be iconic. The original Shirelles version of Will You Love Me Tomorrow, arguably the best song of the 60s, is so clearly a masterpiece that King’s own version could never compete with it. Instead, she sings it slowly and plaintively, with no flattering reverb, making the answer to the title, heartbreakingly, “Probably not”. Ouch!

Lucy Dacus

When I listened to Tapestry from my mom’s CD collection, I was young enough that it didn’t register as good or bad – it just defined what music sounded like to me, and it’s still a foundation of how I understand songwriting. She’s clever in the good way – queen of internal rhyme – and I love how her melodies reinforce the tone of the lyrics. She keeps it simple, but that’s what makes it universal.

I’ll be honest that the song of hers I’ve heard the most is Where You Lead as the Gilmore Girls theme – the version she sings with her daughter. How many hours have I spent sitting on the couch with my mom harmonising to that song? It’s a tradition we’ve carried on a few times during quarantine over the phone.

I also got to see the Broadway show about her, which was wonderful, and really made me realise how special and rare it is to write one song that will carry on a life that is bigger and longer than any human could hope for. And Carole King wrote tons of them! I’ll never forget watching her tribute at the Kennedy Center in 2015 on TV, when Aretha Franklin sang Natural Woman and she stood up from her seat of honour and sang along, arms in the air. I looked up the video to remind myself of it and had a good little ugly cry. I recommend it.

Merrill Garbus, Tune-Yards

Tapestry was a little confusing to me when I first heard it as a full album, maybe in my early 20s. I’d heard plenty of those songs on oldies radio growing up. But why this down-to-earth, subtle take on Natural Woman, on that song by James Taylor? And then that awakening: holy shit, Carole King wrote all those songs? A songwriter I’d known all my life, without knowing her.

Tapestry is performed and produced without pretence. You can hear clearly the subtle twists and turns of the chord progressions, the nuanced choices in harmony. Those vocal harmonies at the end of It’s Too Late and the bridge on Beautiful! Is it wrong to pine for songs of such quality? Songs allowed to shine through as they are, unadorned and utterly remarkable.

I also have to mention the cat on the cover. It may sound trivial, but that was the most “me” I’d ever seen on a record cover, and maybe opened up the possibility that a person could be humble and modest and human rather than superhuman, and be a triumphant musician.

Bethany Cosentino, Best Coast

It was a record my mom used to listen to a lot on the weekends when she could clean the house. I would dance around the living room “helping” her and singing along to I Feel the Earth Move – even though I really didn’t know the lyrics at all, I knew the melody and I knew I loved it. Listening to that album with my mom always made me feel really special because I could tell how much she loved it. To this day, whenever I listen to it, I vividly can remember those Saturday mornings in the house I grew up in.

When I was coming up with a concept for the album cover of our latest record, Always Tomorrow, I used the cover of Tapestry as a big reference point. I knew I wanted it to be shot on film, and I wanted it to showcase a window in my home at the time. Our final album cover changed over time, but the photo on the back is a bit of a homage to Tapestry. I’ve always been really drawn to that album cover. It is so simple, yet it says so much. And it honestly looks the way the album feels: cool, relaxed, cosy and somewhat dark.