Candy Land Was Invented for Polio Wards

A schoolteacher created the popular board game, which celebrates its 70th anniversary this year, for quarantined children. An Object Lesson.

If you were a child at some point in the past 70 years, odds are you played the board game Candy Land. According to the toy historian Tim Walsh, a staggering 94 percent of mothers are aware of Candy Land, and more than 60 percent of households with a 5-year-old child own a set. The game continues to sell about 1 million copies every year.

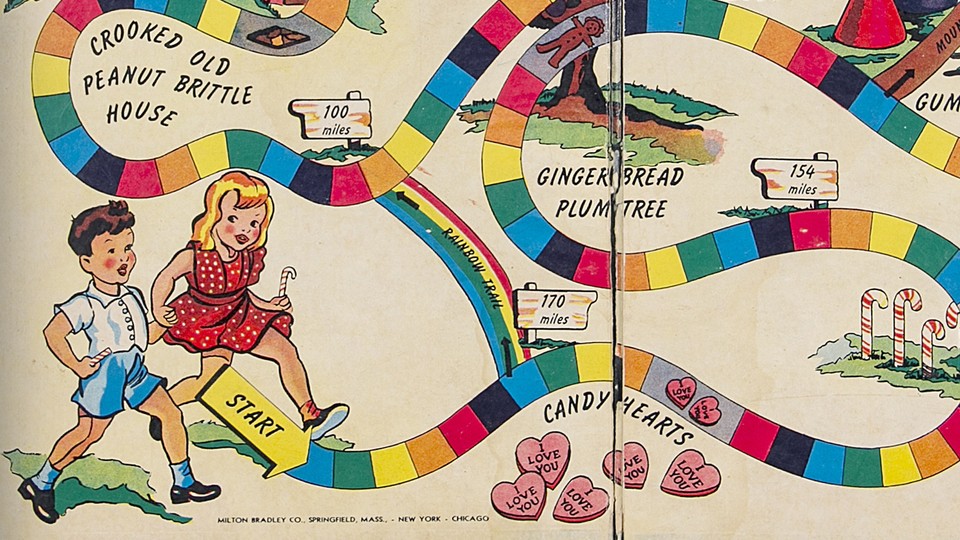

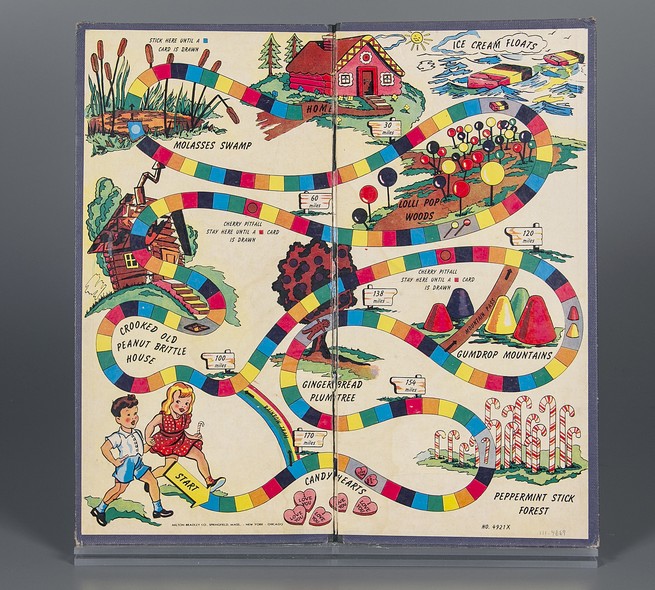

You know how it goes: Players race down a sinuous but linear track, its spaces tinted one of six colors or marked by a special candy symbol. They draw from a deck of cards corresponding to the board’s colors and symbols. They move their token to the next space that matches the drawn color or teleport to the space matching the symbol. The first to reach the end of the track is the winner.

Nothing the participants say or do influences the outcome; the winner is decided the second the deck is shuffled, and all that remains is to see it revealed, one draw at a time. It is a game absent strategy, requiring little thought. Consequently, many parents hate Candy Land as much as their young kids enjoy it.

Yet for all its simplicity and limitations, children still love Candy Land, and adults still buy it. What makes it so appealing? The answer may have something to do with the game’s history: It was invented by Eleanor Abbott, a schoolteacher, in a polio ward during the epidemic of the 1940s and ’50s.

The outbreak had forced children into extremely restrictive environments. Patients were confined by equipment, and parents kept healthy children inside for fear they might catch the disease. Candy Land offered the kids in Abbott’s ward a welcome distraction—but it also gave immobilized patients a liberating fantasy of movement. That aspect of the game still resonates with children today.

Poliomyelitis—better known as polio—was once a feared disease. It struck suddenly, paralyzing its victims, most of whom were children. The virus targets the nerve cells in the spinal cord, inhibiting the body’s control over its muscles. This leads to muscle weakness, decay, or outright fatality in extreme cases. The leg muscles are the most common sites of polio damage, along with the muscles of the head, neck, and diaphragm. In the last case, a patient would require the aid of an iron lung, a massive, coffinlike enclosure that forces the afflicted body to breathe. For children, whose still-developing bodies are more vulnerable to polio infection, the muscle wastage from polio can result in disfigurement if left untreated. Treatment typically involves physical therapy to stimulate muscle development, followed by braces to ensure that the affected parts of the body retain their shape.

Vaccines appeared in the 1950s, and the disease was essentially eradicated by the end of the millennium. But in the mid-century, polio was a medical bogeyman, ushering in a climate of hysteria. “There was no prevention and no cure,” the historian David M. Oshinsky writes.“Everyone was at risk, especially children. There was nothing a parent could do to protect the family.” Like the outbreak of AIDS in the 1980s, polio’s eruption caused fear because its vectors of transmission were poorly understood, its virulence uncertain, and its repercussions unlike those of other illnesses. Initially, polio was called “infantile paralysis” because it struck mostly children, seemingly at random. The evidence of infection was uniquely visible and visceral compared with that of infectious diseases of the past, too. “It maimed rather than killed,” as Patrick Cockburn puts it. “Its symbol was less the coffin than the wheelchair.”

Children of the era faced an unenviable lot, whether infected with polio or not. Gerald Shepherd provides a glimpse of the paranoiac atmosphere of the polio scare and its effects on children in a firsthand account of his San Diego childhood in the late 1940s, at the height of the epidemic. Quarantine and seclusion were the most common preventative measures:

Our parents didn’t know what to do to protect us except to isolate us from other children … One time I stuck my hand through a window and badly cut myself, and despite several stitches and wads of protective bandaging, my father still grounded me that week for fear polio germs might filter in through the sutures.

Kids his age were well aware of what polio could do. “Every time one of our buddies got sick,” Shepherd recollects, “we figured he was headed for the iron lung.” If you caught polio, you would be committed to a hospital with a chance of being forever anchored to a machine. If you didn’t catch it, you would be stuck indoors for the foreseeable future (which, from a child’s perspective, might as well be forever).

For a child of the 1940s or ’50s, polio meant the same thing whether you contracted it or not: confinement.

The Milton Bradley executive Mel Taft said that Abbott, the inventor of Candy Land, was “a real sweetheart” whom he liked immediately. According to Walsh, the toy historian, the two met when Abbott brought Milton Bradley a Candy Land prototype sketched on butcher paper. “Eleanor was just as sweet as could be,” Taft recalled. “She was a schoolteacher who lived in a very modest home in San Diego.”

Details about her life outside this interaction are scant. Curators at the Strong Museum of Play in Rochester, New York, say that the museum has no holdings in its extensive archives from Abbott’s records; they rely on Walsh’s account. Walsh told me that Taft was his only source, and Hasbro, which now owns Milton Bradley, did not respond to a request for records that might verify Abbott as the game’s inventor. Among the few facts researchers have unearthed about her: A phone book containing her number exists in the collections of the San Diego Historical Society (the only trace of her in its archives). And according to some accounts, she gave much of the royalties she earned from Candy Land to children’s charities.

There is reason to believe that Abbott was ideally suited to consider polio from a child’s perspective. As a schoolteacher, she would have been acquainted with children’s thoughts and needs. And in 1948, when she was in her late 30s, she herself contracted the disease. Abbott recuperated in the polio ward of a San Diego hospital, spending her convalescence primarily among children.

Imagine what it must have been like to share an entire hospital ward with children struggling against polio, day after day, as an adult. Kids are poorly equipped to cope with boredom and separation from their loved ones under normal circumstances. But it would be even more unbearable for a child confined to a bed or an iron lung. That was the context in which Abbott made her recovery.

Seeing children suffer around her, Abbott set out to concoct some escapist entertainment for her young wardmates, a game that left behind the strictures of the hospital ward for an adventure that spoke to their wants: the desire to move freely in the pursuit of delights, an easy privilege polio had stolen from them.

From today’s perspective, it’s tempting to see Candy Land as a tool of quarantine, an excuse to keep kids inside in the way Shepherd remembers. The board game gathers all your children in one place, occupying their time and attention. Samira Kawash, a Rutgers University professor, suggests that this is the main way polio informed the game’s development. “The point of Candy Land is to pass the time,” she writes, “certainly a virtue when one’s days are spent in the boring confines of the hospital and an appealing feature as well of a game used to pass the time indoors for children confined to the house.” For Kawash, Candy Land justifies and extends the imprisonment of the hospital, becoming another means of restriction.

But the themes of Candy Land tell a different story. Every element of Abbott’s game symbolizes shaking off the polio epidemic’s impositions. And this becomes apparent if you consider the game’s board and mechanics relative to what children in polio wards would have seen and felt.

In 2010, when he was almost 70 years old, the polio survivor Marshall Barr recalled how only brief escapes from the iron lung were possible. The doctors “used to come and say, ‘You can come out for a little while,’ and I used to sit up perhaps to have a cup of tea,” he wrote, “but then they would have to keep an eye on me because my fingers would go blue and in about 15 minutes I would have to go back in again.” Children would have played Abbott’s early version of Candy Land during these breaks, or in their bed.

Walsh reports that kids loved Abbott’s game, and “soon she was encouraged to submit it to Milton Bradley.” In part, anything that would have reduced boredom would have excited kids during treatment. As the historian Daniel J. Wilson explains, the wards provided little to occupy their young occupants. “In most cases, patients had to find ways to entertain themselves,” he writes.

It was a tall order. The ward’s setup taxed the imagination. The staff, fellow patients, or radio broadcasts would have been a child’s sole company—only doctors and nurses were allowed in the room. Images of polio wards depict a geometry even more rigid and sterile than that of typical hospital settings: row upon row of treatment beds and iron lungs. The children lying supine in iron lungs could see only what was on either side of their head (a line of patients telescoping down the ward) or reflected in mirrors mounted overhead (the floor’s tessellation of bleached tiles).

Candy Land offered a soothing contrast. Repeating tiles line the game’s board, but instead of a uniform, regimented grid, Abbott rearranged them into a meandering rainbow ribbon. Even tracing it with your eyes is stimulating—an especially welcome feature if illness has rendered them the most mobile part of your body.

A colorful chocolate-and-candy landscape seems like the game’s main attraction, but Candy Land’s play revolves around movement. In theme and execution, the game functions as a mobility fantasy. It simulates a leisurely stroll instead of the studied rigor of therapeutic exercise. And unlike the challenges of physical therapy, movement in Candy Land is so effortless, it’s literally all one can do. Every card drawn either compels you forward or whisks you some distance across the board. Each turn promises either the pleasure of unencumbered travel or the thrill of unexpected flight. The game counters the culture of restriction imposed by both the polio scare and the disease itself.

The joy of movement, especially for polio patients, seems to have been integral to Abbott’s design philosophy from the start. The original board even depicts the tentative steps of a boy in a leg brace.

The game also recognizes that mobility entails autonomy. At least part of Candy Land’s appeal is the feeling of independence it provides its young players. In a backstory printed in the game’s instruction manual, the player tokens (in the current edition, four brightly colored plastic gingerbread men) are said to represent the players’ “guides.” They represent the chance to be an active agent, with assistance—an ambulatory adventurer, not a prisoner of the hospital or home. The game may even mark the first time a player feels like a protagonist.

The threat of polio has lessened over time, but Candy Land’s value persists because of what it teaches. This is not to rehash the usual litany of early-childhood skills some Candy Land proponents tout. Yes, the game strengthens pattern recognition. Sure, it can teach children to read and follow instructions. In theory, it shows children how to play together—how to win humbly or lose graciously. But any game can teach these skills.

Candy Land’s lessons are not to be found in the game, but in its results. Now that polio is a distant fear and mobility a power taken for granted, most games of Candy Land disappoint. The rules today are the same as they were in 1949, but something about the proceedings simply does not add up. Eventually, children recognize that they don’t have a hand in winning or losing. The deck chooses for them. An ordained victory is an empty one, without the satisfaction of triumph through skills or smarts.

When children want a more challenging experience, they leave Candy Land behind. And that, in the end, is what makes Candy Land priceless: It is designed to be outgrown. Abbott’s game originally taught children, immobilized and separated from family, to envision a world beyond the polio ward, where opportunities for growth and adventure could still materialize. Today that lesson persists more broadly. The game teaches children that all arrangements have their alternatives. It’s the start of learning how to imagine a better world than the one they inherited. As it has done for generations, Candy Land continues to send young children on the first steps of that journey.

This post appears courtesy of Object Lessons.