San Marino, California

San Marino, California | |

|---|---|

|

Counter-Clockwise: Huntington Library, Huntington Gardens, El Molino Viejo; Huntington Library, El Molino Viejo. | |

| Motto(s): | |

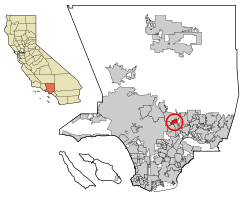

Location of San Marino in Los Angeles County, California | |

| Coordinates: 34°7′22″N 118°6′47″W / 34.12278°N 118.11306°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Los Angeles |

| Incorporated | April 25, 1913[1] |

| Named for | Republic of San Marino |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council Manager |

| • Mayor | Dr. Steven W. Huang[2] |

| • Vice Mayor | Gretchen Shepherd Romey[3] |

| • City Council | City council[4] |

| • City Manager | Philippe Eskandar[5] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3.77 sq mi (9.77 km2) |

| • Land | 3.77 sq mi (9.75 km2) |

| • Water | 0.01 sq mi (0.02 km2) 0.18% |

| Elevation | 564 ft (172 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 13,147 |

| • Estimate (2019)[7] | 13,048 |

| • Density | 3,464.68/sq mi (1,337.85/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| ZIP codes | 91108, 91118 |

| Area code | 626 |

| FIPS code | 06-68224 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1652789[1] |

| Website | ci |

San Marino is a residential city in Los Angeles County, California, United States. It was incorporated on April 25, 1913.[1] At the 2020 United States census the population was 12,513,[8] a decline from the 2010 United States census.[9] The city is one of the wealthiest places in the nation in terms of household income.[10] By extension, with a median home price of $2,699,098,[11] San Marino is one of the most expensive and exclusive neighborhoods in the Los Angeles area.

History[edit]

Origin of name[edit]

The city takes its name from the ancient Republic of San Marino, founded by Saint Marinus who fled his home in Dalmatia (modern Croatia) at the time of the Diocletianic Persecution.[12][13]

The seal of the City of San Marino, California is modeled on that of the republic, depicting the Three Towers of San Marino each capped with a bronze plume, surrounded by a heart-shaped scroll with two roundels and a lozenge (of unknown significance) at the top. The crown representing sovereignty on the original was replaced with five stars, representing the five members of the city's governing body. Beneath the city's seal are crossed palm fronds and orange branches.[12]

The city celebrated its centennial in 2013, including publication by the San Marino Historical Society of a 268-page book, San Marino, A Centennial History, by Elizabeth Pomeroy.[14] In September 2014, this book and author Elizabeth Pomeroy received a prestigious Award of Merit for Leadership in History from the American Association for State and Local History (AASLH).[15]

Early history[edit]

The site of San Marino was originally occupied by a village of Tongva (Gabrieleño) Indians located approximately where the Huntington School is today. The area was part of the lands of the San Gabriel Mission. Principal portions of San Marino were included in an 1838 Mexican land grant of 128 acres to Victoria Bartolmea Reid, a Gabrieleña Indian. (After her first husband, also a Gabrieleño, died in 1836 of smallpox, she remarried Scotsman Hugo Reid in 1837). She called the property Rancho Huerta de Cuati. After Hugo Reid's death in 1852, Señora Reid sold her rancho in 1854 to Don Benito Wilson, the first Anglo owner of Rancho San Pascual. In 1873, Don Benito conveyed to his son-in-law, James DeBarth Shorb, 500 acres (2.0 km2), including Rancho Huerta de Cuati, which Shorb named "San Marino" after his grandfather's plantation in Maryland, which, in turn, was named after the Republic of San Marino located on the Italian Peninsula in Europe.[16][17]

History (1900s)[edit]

In 1903, the Shorb rancho was purchased by Henry E. Huntington (1850–1927), who built a large mansion on the property. The site of the Shorb/Huntington rancho is occupied today by the Huntington Library, which houses a world-renowned art collection, research and rare-book library, and botanical gardens.[18] In 1913 the three primary ranchos of Wilson, Patton, and Huntington, together with the subdivided areas from those and smaller ranchos, such as the Stoneman, White, and Rose ranchos, were incorporated as the city of San Marino.[12]

The first mayor of the city of San Marino was George Smith Patton (1856-1927), the son of a slain Confederate States of America colonel in the U.S. Civil War (also named George Smith Patton, 1833–1864). He married Ruth Wilson, the daughter of Don Benito Wilson. Their son was the World War II general George S. Patton Jr.

To a prior generation of Southern Californians, San Marino was known for its old-money wealth and as a bastion of the region's WASP gentry. By mid-century, however, other European ethnic groups had become the majority.

In the 1980s, San Marino was home to serial killer and con-man Christian Gerhartsreiter.[19] Posing as a member of the British aristocracy and relative of Louis Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten,[19] Gerhartsreiter murdered John and Linda Sohus in 1985.[19][20] Gerhartsreiter then fled to Greenwich, Connecticut and assumed a new alias. The body of John Sohus was discovered in San Marino in 1994[20] and Gerhartsreiter was later convicted of the killing in 2013. Linda Sohus' body has never been found.[19]

In 1970, the city was 99.7% White.[21] By 1990, the city's households were 23.7% Asian.[21]

In 2000, the city's Asian households increased to 40%.[21]

In recent decades, immigrants of Chinese and Taiwanese ancestry have come to represent more than 60% of the population, perhaps due to its location in the San Gabriel Valley, known to be a popular destination for East Asian immigrants.[22]

Geography[edit]

The city is located in the San Rafael Hills, and it is divided into seven zones, based on minimum lot size. The smallest lot size is about 4,500 square feet (420 m2), with many averaging over 30,000 square feet (2,800 m2). Because of this and other factors, most of the homes in San Marino, built between 1920 and 1950, do not resemble the houses in surrounding Southern California neighborhoods (with the exception, perhaps, of neighboring portions of Pasadena). San Marino has also fostered a sense of historic preservation among its homeowners. With minor exceptions, the city's strict design review and zoning laws have thus far prevented the development of large homes found elsewhere in Los Angeles.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 3.8 square miles (9.8 km2), virtually all land.

San Marino is highly restrictive of commercial operations in the city. It is one of the few cities that requires commercial vehicles to have permits to work within the city. The rationale is that commercial vehicle operators and service providers, such as gardeners, pool service providers and maintenance workers, are more likely to cause social disruption within the city, and so must be preauthorized for crime control and prosecutorial purposes. This regulation and others, including the bans on apartment buildings, townhouses, and overnight parking, are some of the more obvious examples.

Demographics[edit]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 584 | — | |

| 1930 | 3,730 | 538.7% | |

| 1940 | 8,175 | 119.2% | |

| 1950 | 11,230 | 37.4% | |

| 1960 | 13,658 | 21.6% | |

| 1970 | 14,177 | 3.8% | |

| 1980 | 13,307 | −6.1% | |

| 1990 | 12,959 | −2.6% | |

| 2000 | 12,945 | −0.1% | |

| 2010 | 13,147 | 1.6% | |

| 2020 | 12,513 | [23] | −4.8% |

| 2022 (est.) | 12,039 | [24] | −3.8% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[25] | |||

2020[edit]

The 2020 United States census[8] reported that San Marino's population was 12,513 residents. This is a decline from the 2010 census, where the population was 13,147.[26] Asian Americans constituted the majority of San Marino residents at 8,061 (64.4%). White Americans were the second-largest group at 4,484 residents (35.8%). African Americans were the third-largest group at 109 residents (0.9%). American Indians or Native Americans represented 94 residents (0.8%). Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders represented 92 residents (0.7%). 722 residents responded as 'some other race' (5.8%).[8] 888 residents identified as Hispanic or Latino American (7.1%).

The largest age demographic were 15-19 year olds, representing 1,064 residents (8.5%). The second-largest age demographic were 55-59 year olds, representing 1,016 residents (8.1%). 9,892 residents (79.1%) were 18 years old or older and 3,519 (28.1%) were over the age of 62.[8]

According to the 2020 Census, San Marino had a median household income of $174,622, with 6.1% of the population living below the federal poverty line.[27]

2010[edit]

The 2010 United States Census[26] reported that San Marino had a population of 13,147. The population density was 3,483.4 inhabitants per square mile (1,344.9/km2). The racial makeup of San Marino was 5,434 (41.3%) White (37.1% Non-Hispanic White),[28] 55 (0.4%) African American, 5 (0.0%) Native American, 7,039 (53.5%) Asian, 2 (0.0%) Pacific Islander, 198 (1.5%) from other races, and 414 (3.1%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 855 persons (6.5%).

The census reported that 13,066 people (99.4% of the population) lived in households, 81 (0.6%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 0 (0%) were institutionalized.

There were 4,330 households, out of which 1,818 (42.0%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 3,220 (74.4%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 367 (8.5%) had a female householder with no husband present, 143 (3.3%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 42 (1.0%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 22 (0.5%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. Of all households, 531 (12.3%) were made up of individuals, and 359 (8.3%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.02. There were 3,730 families (86.1% of all households); the average family size was 3.28.

The population was spread out, with 3,422 people (26.0%) under the age of 18, 712 people (5.4%) aged 18 to 24, 2,353 people (17.9%) aged 25 to 44, 4,351 people (33.1%) aged 45 to 64, and 2,309 people (17.6%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 45.3 years. For every 100 females, there were 92.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 87.7 males.

There were 4,477 housing units at an average density of 1,186.2 per square mile (458.0/km2), of which 3,959 (91.4%) were owner-occupied, and 371 (8.6%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 0.5%; the rental vacancy rate was 6.5%; 11,834 people (90.0% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 1,232 people (9.4%) lived in rental housing units.

2000[edit]

As of the census[29] of 2000, there were 12,945 people, 4,266 households, and 3,673 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,430.5 inhabitants per square mile (1,324.5/km2). There were 4,437 housing units at an average density of 1,175.8 per square mile (454.0/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 51.98% White, 0.15% African American, 0.05% Native American, 47.7% Asian, 0.08% Pacific Islander, 1.04% from other races, and 2.30% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3.25% of the population. More than one-third of the city's population, 33.3%, was Chinese.[30]

There were 4,266 households, out of which 42% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 75% were married couples living together, 8.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 13.9% were non-families. Of all households 12% were made up of individuals, and 7.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.03 and the average family size was 3.29.

In the city, the age distribution of the population showed 26.5% under the age of 18, 6.4% from 18 to 24, 21.5% from 25 to 44, 29.4% from 45 to 64, and 16.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 43 years (this was older than average age in the U.S.).[31] For every 100 females, there were 93.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 89.1 males.

San Marino is one of the county's cities with the highest proportion of residents of Asian ancestry. These were the ten neighborhoods in Los Angeles County with the largest percentage of Asian residents, according to the 2000 census:[32]

- Chinatown, 70.6%

- Monterey Park, 61.1%

- Cerritos, 58.3%

- Walnut, 56.2%

- Rowland Heights, 51.7%

- San Gabriel, 48.9%

- Rosemead, 48.6%

- Alhambra, 47.2%

- San Marino, 46.8%

- Arcadia, 45.4%

Arts and culture[edit]

Notable sites[edit]

San Marino is the location of the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. In 1919, Henry E. Huntington provided limited access to his art collection, library containing the rare books and historical documents, and botanical collection. The Huntington's library contains 8 million manuscripts, 440,000 rare books, 454,000 reference books, 900,000 prints and ephemera, 777,000 photographs, and 300,000 digital files.[33] The Huntington's art collections are housed in his large Neoclassical–Palladian mansion and feature European and American art spanning more than 500 years. In addition, the surrounding botanical gardens span approximately 120 acres and contain more than a dozen themed gardens. Collectively, the institution is known as "The Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens", or as "The Huntington," to the public.[34]

El Molino Viejo ("The Old Mill"), completed about 1816 as a grist mill for Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, is in San Marino. The original two-story structure measured 53 feet (16 m) by 26 feet (7.9 m). It is the oldest commercial building in Southern California.[35][36] The town is located on the former lands of the historic Rancho Huerta de Cuati.[37]

The Edwin Hubble House: From 1925 to 1953, this two-story stucco home was the residence of Edwin Hubble, one of America's great 20th-century astronomers, who, among other accomplishments, discovered extragalactic nebulae and their separation from each other. It is a National Historic Landmark.[38]

The Michael White Adobe House is located on the campus of San Marino High School and houses the San Marino Historical Society archives.[39]

The University of Southern California owns a house in San Marino which is used as the residence of the president of the university. The residence and grounds often are used for university events.

Across from City Hall, at the northeast corner of Huntington Drive and San Marino Avenue, is the Centennial Clock, donated to the community in 2005 by the Rotary Club of San Marino in celebration of Rotary International's 100th anniversary. Dedicated on July 4, 2005, the nineteen foot high clock includes a time capsule with artifacts donated by residents and community organizations which is to be opened on July 4, 2039, to mark the 100th anniversary of the Rotary Club of San Marino.[40]

In the middle of San Marino lies Lacy Park, a 30-acre (120,000 m2) expanse of grass and trees. Originally named Wilson Lake in 1875, the land was purchased by the city in 1925 and dedicated as a park. It is one of the few neighborhood parks that charge for admission, with a $5 fee for non-San Marino residents on weekends. A picnic area is often the site of musical concerts, civic events and pancake breakfasts. Within the park are two walking loops: an inner loop of approximately 3/4 mile in length, and an outer loop of approximately 1-mile (1.6 km) in length. Dogs are welcome with their owners, providing they are on a leash.[41] In recent years, proposals from SMHS alumni Brent and Derek Barker to build a dedicated dog park on the unlandscaped western edge of the park have been shelved due to strident opposition from some of the city's elderly residents.[42] The park includes six championship tennis courts and a pro shop, administered by the San Marino Tennis Foundation. At the west entrance of the park is the Rose Arbor, which is of special significance for the people of San Marino. It is sixty years old and has long been a source of beauty and tranquility to many residents. In recent years the care and upkeep of the Rose Arbor itself has been augmented by private donations from residents who have chosen to sponsor individual posts.[41] The park recently built a memorial to General George S. Patton (a native of San Marino) and also a large memorial to the Armed Forces along with a statue of a sad soldier. The memorial includes the names of all military personnel from San Marino.[35]

The city's local newspaper office is located on Mission St., in the city's “old town”. The San Marino Tribune has been the official newspaper of the city since 1929. There are two sections of the weekly paper, an "A" section and a "B" section, the distinction being that it covers San Marino news as well as news in Pasadena, San Gabriel, Alhambra, Arcadia and South Pasadena.[43]

Government[edit]

Local government[edit]

Governing the City of San Marino is a city council of five members, elected by the people for a four-year term. Elections are consolidated with the county and are held on the first Tuesday, following the first Monday in November of odd numbered years. Terms are staggered so that three seats are available during one election cycle and two seats are available during the next cycle. In 2015, the state enacted a law to require municipalities to consolidate their elections beginning January 1, 2018.[44] The five council members serve without any financial compensation and elect one of their own members as Mayor.

The current city council members are:

- Mayor: Dr. Steven W. Huang (2024)[45]

- Vice mayor: Gretchen Shepherd Romey (2024)

- Council members: Steven Talt, Calvin Lo, Tony Chou (2022)

San Marino's Fiscal Year 2019-2020 operating budget is $25,807,192.[46] The city manager reports that for FY 2019-2020 "personnel costs comprise 2/3rds of the operating budget, and the largest portion of the increase from FY 2018-2019 is in that area."[46]

List of mayors[edit]

This is a list of San Marino mayors by year:

- 1913-1922 George S. Patton

- 1922 William L. Valentine

- 1922-1924 George S. Patton

- 1924-1942 Richard H. Lacy

- 1980-1984 Lynn P. Reitnouer [47]

- 1990 Suzanne Crowell [48]

- 2001 Matthew Lin, the first Chinese-American mayor of San Marino[49][50]

- 2009 Eugene Sun

- 2012 Richard Sun [51]

- 2013 Richard Ward [52]

- 2015 Eugene Sun [53]

- 2016 Allan Yung [54][55]

- 2017 Richard Sun [56]

- 2018 Steve Talt [57]

- 2019 Steven Huang[58]

- 2020 Gretchen Shepherd Romey[59]

- 2021 Ken Ude[60]

- 2022 Susan Jakubowski

- 2023 Steve Talt

- 2024 Steven Huang[61]

State and federal representation[edit]

In the House of Representatives, San Marino is located in California's 27th congressional district, represented by Democrat Judy Chu.[62]

Education[edit]

On September 9, 1913, the first San Marino school was opened at the corner of Monterey Road, then called Calle de Lopez, and Oak Knoll, in what was known as the Old Mayberry Home. There were three teachers and thirty-five pupils from kindergarten through the eighth grade; high school students attended South Pasadena High School until San Marino High School was founded in 1952. San Marino High School graduated its first class in 1956. The high school's mascot, "The Titans", comes from Mt. Titano, in the Republic of San Marino.[12]

San Marino High School is situated on the former site of Carver Elementary School. In 1996, the high school reconstruction was begun and the school is now equipped with new laboratories, classrooms, and Ethernet connections, supported mainly by bond issues and rigorous fund-raising by the San Marino Schools Endowment. The new buildings include a brand new cafeteria, orchestra and band room, dance studio, journalism lab, and renovated auditoriums, as well as a renovated baseball field and a brand new football field/track.[63] The School Board's budget totals around $3 million in a given year.

San Marino High School is part of the San Marino Unified School District. Its public funding is supplemented by private donations raised through the San Marino Schools Foundation. Each year, the Foundation raises funds necessary to balance the District's budget. To date[when?], the San Marino Schools Foundation has contributed $18,268,485 to the schools since its inception in March 1980.[63] From 2013 to 2017, the district was noted for having the highest percentage of students who met and exceeded the California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress standards.[64]

The San Marino Unified School District has been ranked as the top unified school district in the state of California for eighteen consecutive years, including 2018.[65] Each of its public primary schools has also been honored as a California Distinguished School and a National Blue Ribbon School.[66]

There are four public schools in San Marino Unified School District:

- Valentine Elementary School

- Carver Elementary School

- Huntington Middle School

- San Marino High School

The two elementary schools offer instruction for grades K-5, the middle school for grades 6-8, and the high school for grades 9-12. The middle school was named Henry E. Huntington School, after San Marino's "first citizen."[63] In 1953, a new K. L. Carver Elementary was completed at its current location on San Gabriel Boulevard and was named after K. L. Carver, a long-serving school board member.[63][67] Stoneman Elementary School, named for Governor George Stoneman, who had resided in San Marino, is no longer used for instruction by San Marino School District. The former school is now leased by the San Marino City Recreation Department and houses San Marino Unified School District special education staff.[63]

In November 2007, San Marino High School was ranked 82nd on a list of the best high schools in the nation, according to U.S. News & World Report.[68]

Private schools[edit]

- Southwestern Academy, a private college preparatory school, was founded on April 7, 1924. The campus was part of an original Spanish grant (the old ranch grew orange and avocado trees) and the land was subsequently legalized[clarification needed] by Abraham Lincoln. "Southwestern Academy" was named to capture the distinctive spirit of the Southwestern United States. Pioneer Hall, which was Southwestern's original campus building, was the home of then-Governor George Stoneman.[63]

- Saints Felicitas and Perpetua school is a Catholic school that offers education in grades K-8. The city took the Archdiocese of Los Angeles to the Supreme Court[clarification needed] to block the construction of the school, as it was attempting to demolish a historical site called Casa Blanca or the Old Adobe (at one time the Luther Harvey Titus Adobe) to make way for the new school.[citation needed] Saints Felicitas & Perpetua School was completed and dedicated in 1950.[63]

Media[edit]

Newspapers[edit]

The city is served by the San Marino Tribune,[69] a paid community weekly newspaper and the San Marino Outlook, also a community weekly newspaper.[70]

Infrastructure[edit]

The city currently is served by the San Marino Police Department.[71]

The Crowell Public Library opened in 2008.[35]

Notable people[edit]

- Lee Baca, former sheriff of Los Angeles County

- Andrew D. Bernstein, senior director, NBA Photos

- John Bryson, president of Edison International and former United States Secretary of Commerce

- Henry Bumstead, production designer, winner of two Academy Awards, To Kill a Mockingbird

- Drucilla Cornell, author, chairman in jurisprudence at the University of Cape Town; S.M.H.S. graduate

- Christine Craft, attorney, KGO radio personality and former television news anchor

- Mark Cronin, television producer

- Peter B. Dervan, awarded the National Medal of Science in Chemistry, professor at Caltech

- Darren Dreifort, former MLB pitcher, Los Angeles Dodgers

- Christian Gerhartsreiter, serial imposter and convicted murderer, lived here using the pseudonym Christopher Chichester

- James G. Ellis, dean of the Marshall School of Business at USC

- Jim Gott, former MLB pitcher for Los Angeles Dodgers, Pittsburgh Pirates, San Francisco Giants

- Pat Haden, athletic director of USC and former pro quarterback for the Los Angeles Rams

- John Hart, actor, the Masked Man in The Lone Ranger from 1952 to 1954

- Stephen Hillenburg, animator, writer and television producer, creator of SpongeBob SquarePants

- Edwin Hubble, astronomer, changed view of universe per galaxy redshift, leading to Big Bang cosmology

- Henry E. Huntington, railroad executive, founder of The Huntington Library

- Jaime Jarrín, Spanish-language broadcaster for Los Angeles Dodgers, recipient of the Ford C. Frick Award, Baseball Hall of Fame

- Jane Kaczmarek, actress, Saturday Night Live, Pleasantville, Malcolm in the Middle

- Howard Kazanjian, film producer for Raiders of the Lost Ark, Return of the Jedi; former vice president at Lucasfilm

- Herman Leonard, jazz photographer, photo collection is in the permanent archives in the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C.

- Thomas Mack, former right guard, NFL, Los Angeles Rams

- Elliot Meyerowitz, chairman, Division of Biology at the California Institute of Technology

- Robert A. Millikan, experimental physicist, awarded the 1923 Nobel Prize in Physics for the electron charge

- Adolfo Müller-Ury, Swiss-born American painter, noted for portraits of popes and presidents

- Charles A. Nichols, animation director, Hannah-Barbara, Walt Disney

- C. L. Max Nikias, president of USC

- Nancy O'Dell, television personality, Access Hollywood

- Merlin Olsen (1940-2010), former defensive lineman, NFL, Los Angeles Rams, actor (Little House on the Prairie), sportscaster NBC.[72]

- Stephan Pastis, comic artist, Pearls Before Swine

- George S. Patton Sr. (1856-1927), attorney, first mayor of San Marino, California (1913-1922)

- George S. Patton Jr. (1885-1945), general in the U.S. Army, World War II

- Michael W. Perry, former chairman and CEO of IndyMac Bank

- Steven B. Sample, former president of USC

- Rob Schneider, actor, comedian. Saturday Night Live, Deuce Bigalow: Male Gigolo, The Hot Chick and Grown Ups.

- Donald Segretti, political operative, involved in Watergate

- Tim Sloan, ex-CEO of Wells Fargo[73]

- Joachim Splichal, chef and founder of the Patina Restaurant Group

- George Stoneman, 15th governor of California, general in the Civil War Union Army

- Bradley Whitford, actor, The West Wing, Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip, Billy Madison

- Yanis C. Yortsos, dean of the Viterbi School of Engineering at USC

- Joseph Wambaugh, writer, including the noovel The New Centurions and the nonfiction book The Onion Field

- Ahmed H. Zewail, awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, femtochemistry, chair of Chemistry at Caltech

In popular culture[edit]

Movies[edit]

Father of the Bride, The Wedding Singer, In Name Only, and The Holiday were filmed in San Marino.[74]

Television[edit]

Many TV shows, like Alias, The Office, Parks and Recreation, The West Wing, Felicity, and The Good Place, have been filmed on location in San Marino.[citation needed]

See also[edit]

- California's 25th State Senate district

- History of the Chinese Americans in Los Angeles

- Governor Stoneman Adobe, Los Robles California Historical Landmark

- El Molino Viejo California Historical Landmark

References[edit]

- ^ a b c "San Marino". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ "Dr. Steven W. Huang". Retrieved December 14, 2023.

- ^ "Gretchen Shepherd Romey". Retrieved December 14, 2023.

- ^ "Mayor & City Council". www.cityofsanmarino.org. Archived from the original on April 5, 2023. Retrieved June 10, 2023.

- ^ "Philippe Eskandar". Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved June 12, 2023.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001), San Marino city, California". American FactFinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved September 4, 2019.

- ^ del Giudice, Vincent; Lu, Wei. "America's 100 Richest Places". Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg.

- ^ "Housing in San Marino, CA". Berkshire Hathaway. Archived from the original on October 16, 2018. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

- ^ a b c d "City of San Marino, CA - About Our City". Cityofsanmarino.org. September 9, 1917. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- ^ K.Maskarin. "St. Marino, the founder of the San Marino republic - the legend, island Rab Croatia". Kristofor.hr. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- ^ Pomeroy, Elizabeth. San Marino, A Centennial History. San Marino Historical Society, 2012.

- ^ http://about.aaslh.org/awards/ Archived 2014-10-06 at the Wayback Machine American Association for State and Local History Awards

- ^ "Historic Adobes of Los Angeles County". LAOKay.com. Archived from the original on August 25, 2014. Retrieved December 28, 2013.

- ^ "{title}". Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

- ^ "About The Huntington". Huntington.org. Archived from the original on December 30, 2013. Retrieved December 28, 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Rockefeller imposter and convicted felon born". HISTORY. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ a b Redd, Wyatt (March 19, 2022). "Meet The Twisted Con Man Who Passed Himself Off As A Rockefeller And Got Away With Murder For 28 Years". All That's Interesting. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ a b c "How an Exclusive Los Angeles Suburb Lost its Whiteness". Bloomberg.com. citylab.com. August 27, 2012. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ "City of San Marino, CA - Employment Opportunities". Cityofsanmarino.org. Archived from the original on January 7, 2010. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- ^ "Explore Census Data".

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: San Marino city, California".

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ a b "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - San Marino city". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/sanmarinocitycalifornia,US/INC110221

- ^ "San Marino (City) QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau". Archived from the original on August 30, 2012. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Census Bureau, 2000 Census factsheet". Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- ^ "San Marino, California Demographics - City and State Information - Population and Housing Data". muninetguide.com. Archived from the original on August 3, 2010. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ "Asian", Mapping L.A., Los Angeles Times

- ^ "About". The Huntington. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- ^ http://www.huntington.org/ Archived 2008-07-03 at the Wayback Machine access date: 6/2/2010

- ^ a b c "San Marino California City Guide". Pasadenaviews.com. Archived from the original on August 31, 2010. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- ^ "The Old Mill ~ El Molino Viejo". Old-mill.org. Archived from the original on March 29, 2010. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- ^ http://www.old-mill.org/ Archived 2010-05-07 at the Wayback Machine access date: 6/2/2010

- ^ "National Historic Landmarks Program (NHL)". Tps.cr.nps.gov. December 8, 1976. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- ^ http://www.smnet.org/comm_group/historical/ Archived 2010-05-18 at the Wayback Machine access date: 6/2/2010

- ^ "{title}". Archived from the original on February 21, 2015. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- ^ a b "City of San Marino, CA - Lacy Park". Ci.san-marino.ca.us. Archived from the original on May 29, 2010. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- ^ "Dog Park". Sanmarinotribune.com. June 3, 2014. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- ^ "San Marino". Sanmarinotribune.com. Archived from the original on September 14, 2010. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- ^ "SB-415: Voter Participation". Archived from the original on April 24, 2016. Retrieved April 8, 2016.

- ^ "Talt Steps Down as San Marino Mayor, Huang Takes Reins - San Marino Tribune". December 31, 2023. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- ^ a b Marlowe, Marcella (June 12, 2019). "Fiscal Year 2019-2020 Adopted Operating and Capital Budget" (PDF). cityofsanmarino.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 29, 2019. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

- ^ Lehman, Mitch (December 9, 2016). "Forest Lawn Names Board Room After Former Mayor Reitnouer". sanmarinotribune.com. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ "Huntington Hospital Has New Board". Los Angeles Times. February 9, 2006. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- ^ "Major Funding for Chinese Garden: Joy and Matthew Lin". huntington.org. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- ^ "Former San Marino Mayor Running for Local State Assembly Seat". patch.com. December 13, 2020. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- ^ "City Council Chooses New Mayor". patch.com. March 14, 2012. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ "Red Cross Kicks Off 100 Years of Service in Pasadena Friday". pasadenanow.com. November 8, 2013. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ "Mayor Eugene Sun to Hold Community Meeting Thursday". sanmarinotribune.com. May 27, 2015. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- ^ "Huang, Talt Take Council Seats". sanmarinotribune.com. December 9, 2015. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- ^ "A Changing of the Guard in San Marino". outlooknewspapers.com. December 17, 2015.

- ^ Kurdoghlian, Kevork (December 22, 2016). "Newly Elected Mayor Richard Sun Shares Hopes For New Term". sanmarinotribune.com. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ Hill, Zane (December 21, 2017). "New Mayor Talt Outlines Plans". outlooknewspapers.com. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ Lehman, Mitch (December 7, 2018). "Huang Set To Be City's Next Mayor". sanmarinotribune.com. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ Hannah, Skye (December 13, 2019). "Shepherd Romey Named Mayor". sanmarinotribune.com. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ "Mayor Reiterates Plans in State of the City Address – San Marino Tribune". Retrieved May 7, 2021.

- ^ "Talt Steps Down as San Marino Mayor, Huang Takes Reins - San Marino Tribune". December 31, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ^ "{title}". Archived from the original on September 28, 2018. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Our History". Archived from the original on July 2, 2018. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- ^ "San Marino Unified School District is #1 in the State". San Marino Unified School District. October 2, 2018. Archived from the original on October 16, 2018. Retrieved October 16, 2018.

- ^ "SMUSD Still Atop State, According to Standardized Tests". San Marino Tribune. October 5, 2018. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- ^ Knoll, Corina (September 22, 2009). "Piece of San Marino history a victim of the times". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 27, 2010. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- ^ "San Marino High School". Sanmarinohs.org. Archived from the original on November 8, 2009. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- ^ "Gold Medal Schools - U.S. News & World Report". Archived from the original on December 31, 2011. Retrieved December 9, 2007.

- ^ "San Marino Tribune". sanmarinotribune.com. Archived from the original on April 8, 2018. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ "San Marino 'Arts Rock!' Showcases April 1 - Outlook Newspapers". outlooknewspapers.com. March 23, 2017. Archived from the original on April 9, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ "Police Department - San Marino, CA - Official Website". www.ci.san-marino.ca.us. Archived from the original on March 20, 2018. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ "Mediterranean Estate, San Marino, California 1984". glen-hampton-gardens-designs.com. Archived from the original on January 26, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- ^ Dreier, Peter (October 2, 2012). "Putting Names And Faces To The 1 Percent: Wells Fargo's Tim Sloan". huffingtonpost.com. Archived from the original on September 30, 2017. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ "Filming Locations of The Wedding Singer". Seeing-stars.com. Archived from the original on July 2, 2018. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- James T. Maher, 1975. The Twilight of Splendor: Chronicles of the Age of American Palaces. - A chapter is on Huntington's San Marino estate.