Egypt's last pharaoh was the 'love child' of Caesar and Cleopatra

Caesarion embodied his mother's alliance with Rome, but assassination and war would bring about his death at age 17, ending Ptolemaic rule in Egypt.

Ptolemy Caesar “Theos Philopator Philometor”—“Ptolemy Caesar, The God Who Loves His Father and Mother”—became king of Egypt at the tender age of three. His alleged father, Julius Caesar, had been assassinated several months earlier, and his mother, Queen Cleopatra VII, placed him on the throne to solidify her power as queen of Egypt.

Better known to history by his Greek nickname “Caesarion,” or “little Caesar,” Cleopatra’s son reigned only a short time; his rule ended with his murder, shortly after the suicide of Cleopatra in 30 B.C. The deaths of mother and son brought an end to the Ptolemaic line of rulers who had controlled Egypt since the time of Alexander the Great.

Family quarrels

Caesarion’s story began when his grandfather, Ptolemy XII, named his two oldest children, 18-year-old Cleopatra and 10-year-old Ptolemy XIII, as co-heirs. They would serve together under the guardianship of Rome. Because Egypt had become a Roman protectorate during the elder Ptolemy’s rule, Romans had a say in who would be ruling Egypt. (Watch how Cleopatra achieved immortality through her personal story of love and tragedy.)

After their father’s death in 51 B.C., Ptolemy and his sister were symbolically wed, but there was no love between them, familial or otherwise. The Ptolemaic kings and queens had a long family tradition of competing for the throne: sibling against sibling or parent against child. Two years later, Ptolemy’s advisers tried to move against Cleopatra to make the young boy the sole ruler.

As the two Egyptian siblings were squabbling over their throne, Rome was in the middle of its own power struggle. Two of its great military heroes, Julius Caesar and Pompey the Great, were engaged in a civil war and were looking for alliances. Pompey needed Egypt and decided to back Ptolemy XIII over his sister, who went into exile. Far from the capital, Cleopatra established her own base of operations where she raised an army and bided her time.

In the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 B.C., Caesar defeated Pompey, who fled to Alexandria. In a reversal, the young Ptolemy had Pompey executed and presented his head to Julius Caesar when he swept into Egypt later that year. Caesar was saddened and disgusted: Ancient historian Plutarch wrote in the first century A.D. how Caesar had “turned away in horror [when] presented the head of Pompey, but he accepted Pompey’s seal-ring, and shed tears over it.”

This gross miscalculation on the young pharaoh’s part was a prime opportunity for Cleopatra and her forces. She smuggled herself into Alexandria for a meeting with Caesar and won him to her cause. He supported her claim to the throne, sparking an uprising of Ptolemy’s supporters who were defeated. The young king was killed, and Caesar placed the 21-year-old Cleopatra VII on the throne. She would co-rule, in name, with a younger brother, Ptolemy XIV. To consolidate the alliance, Cleopatra invited Caesar, 30 years her senior, to stay in Egypt with her.

Son of Rome and Egypt

For two months Cleopatra entertained Caesar, revealing to him the charms that both the Nile Valley and she herself had to offer. Plutarch wrote: “[Caesar] often feasted with her until dawn; and they would have sailed together . . . to Ethiopia.” By the time Caesar left Egypt, Cleopatra was pregnant. She gave birth to a boy in 47 B.C. and openly proclaimed Julius Caesar the father. Egyptian priests began to teach that the god Amun had incarnated himself in the person of Caesar, the most powerful man in the world at the time, to father the baby prince. (Meet history's top ten, red-hot power couples.)

At the end of 46 B.C., Cleopatra visited Rome at Caesar’s invitation, bringing Caesarion and all the royal pageantry of her court. Plutarch wrote that Caesar “would not let her return to Alexandria without high titles and rich presents. He even allowed her to call the son whom she had borne him by his own name.” Caesar welcomed Cleopatra and her family in one of his suburban villas, the Horti Caesaris, showering her with official honors.

Many Romans remarked that the child looked markedly like Julius Caesar. Mark Antony, Caesar’s lieutenant, told the Senate that Caesar had acknowledged to his closest friends that Caesarion was indeed his son. If Cleopatra’s claims were believed, Caesarion was Caesar’s only surviving child. His daughter, Julia, who had been married to Pompey, died in childbirth in 54 B.C.

Despite the cool reception from the Roman people, Julius Caesar was optimistic about the relationship between Rome and Egypt. He erected a statue of Cleopatra in the Temple of Venus Genetrix. This era marked what Caesar saw as the beginning of an ambitious imperial project. Rumors spread that he was even mulling a transfer of the imperial capital to Alexandria. (For most Romans, becoming a citizen was the path to power.)

His plans would not be realized, for Caesar was assassinated on the Ides of March in 44 B.C. He never acknowledged Caesarion as his heir and instead had written in his will that his great-nephew, Gaius Octavius (Octavian), was his heir. Cleopatra and Caesarion were in Rome when Caesar was killed. Realizing that their lives were in danger, Cleopatra decided to return to Egypt immediately.

Life after Caesar

As soon as she arrived back in Alexandria, the queen moved to consolidate her power. Sources say she had her brother and co-ruler, Ptolemy XIV, poisoned and then appointed her toddling son as her co-regent. From this point, Caesarion was officially recognized as Ptolemy XV Caesar.

In Rome Octavian refused to recognize the lineage of Egypt’s young co-regent. With calculated timing, the late Julius Caesar’s right-hand man and confidante Gaius Oppius published a book in which he claimed that Caesarion was not the son of Caesar at all. It was a warning to Cleopatra to tread carefully with the new masters of Rome.

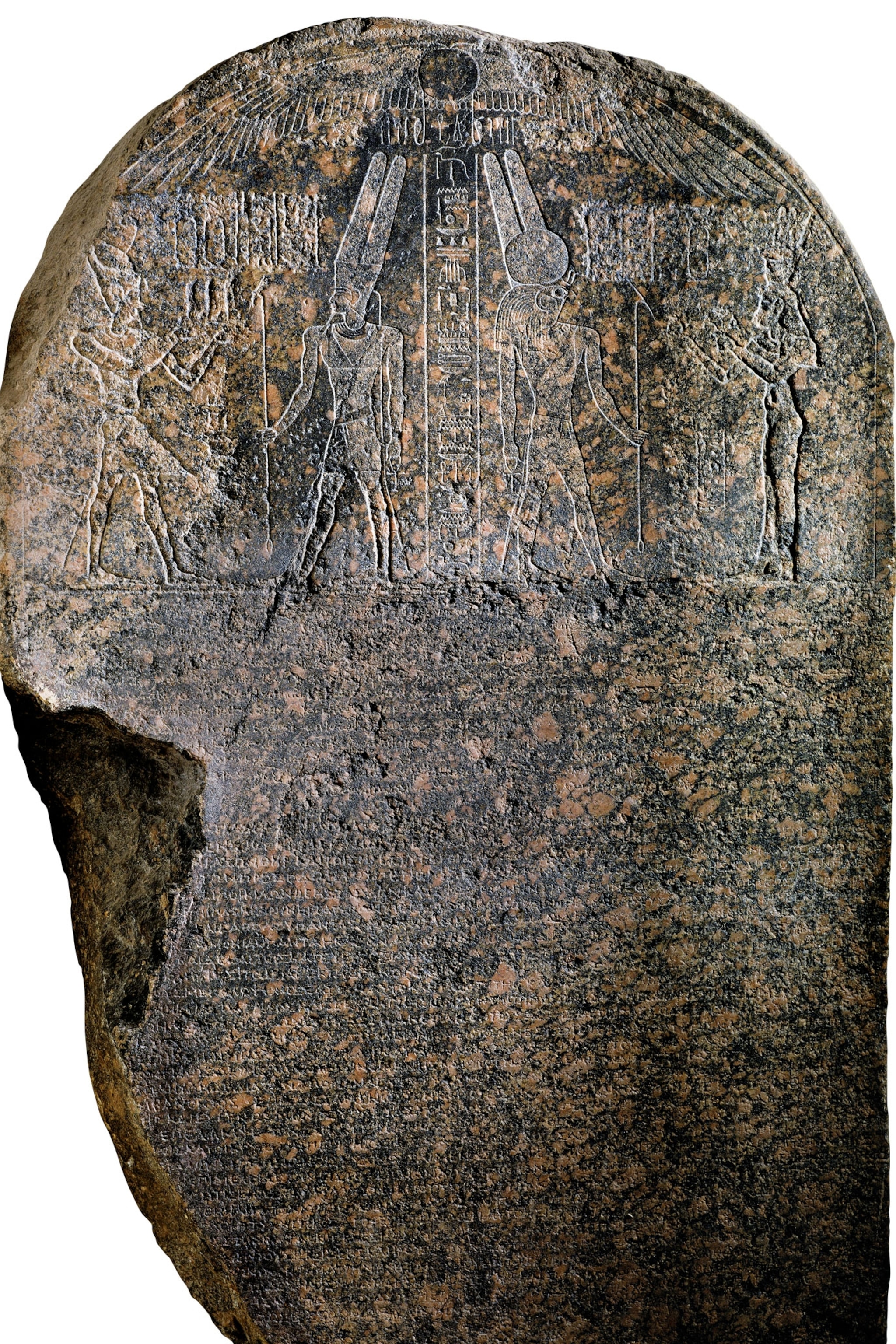

Portraits of a prince

The earliest existing depictions of Caesarion appear on coins minted in Cyprus in 44 B.C. Even though the boy was then a toddler, he was still shown as a baby in his mother’s arms. There are later works of art in which Caesarion appears as a young man, wearing the typical Egyptian headdress (nemes) and kilt (shandyt), as in traditional images of the pharaohs.

Many representations of Caesarion associate him with the Egyptian god Horus, the son of Isis and Osiris. After Osiris is violently murdered by his rival Set, Isis must protect her son and restore the rightful king to the throne. Cleopatra smartly used this imagery to win support for Caesarion and cast herself in the role of divine maternal protector.

Caesarion’s fortunes were revived in 42 B.C. when Mark Antony arrived in Egypt as Roman triumvir in charge of the eastern provinces. He was seeking a way to bring down fellow triumvir Octavian, and in 41 B.C. he summoned Cleopatra to Tarsus. The queen navigated this important meeting just as carefully as her first with Julius Caesar.

For the sake of her kingdom and of her son, Caesarion, she took Antony on a sumptuous cruise and a love affair ensued. This relationship has long been regarded as one of history’s most passionate, but historian Mary Beard revealed its more practical side: “Passion may have been one element of it. But their partnership was underpinned by something more prosaic: military, political, and financial needs.” (See inside Cleopatra and Mark Antony’s decadent love affair.)

Antony spent the winter of 41-40 B.C. in Egypt with Cleopatra. From their union twins were born and named after the astral deities: Alexander Helios (Sun) and Cleopatra Selene (Moon). Later, they had another son named Ptolemy Philadelphus. During this time, Cleopatra was also expanding her empire, gaining territory for Caesarion in southern Syria, Cyprus, and northern Africa.

Cleopatra’s greatest moment came during a ceremony held at the Alexandria gymnasium in 34 B.C., when Antony officially recognized her as queen of Egypt and bestowed on Caesarion the title “King of Kings.” Antony also formally recognized Caesarion as the legitimate son of Julius Caesar. Antony granted his three children with Cleopatra the title of royal highnesses and to his son Alexander Helios he promised territories and kingdoms.

The provocation was too much for Octavian and he declared war on Cleopatra and Antony. On September 2, 31 B.C., he vanquished their forces at the Battle of Actium. The defeated pair retreated to Alexandria. Cleopatra decided it was safer to send Caesarion out of the city. He headed south in the company of his tutor, who took him up the Nile to the village of Copt (Qift), not far from Thebes. From there, caravans set off, passing through the eastern desert to the commercial port of Berenice, on the shores of the Red Sea. Caesarion’s only feasible escape route was across these inhospitable lands. If he made it to Berenice, he would have a chance to get out of Egypt and set sail for Arabia or even to India.

While making his way to the port that might have allowed him a route to exile, Caesarion learned that Roman troops had entered Alexandria and that his mother and Mark Antony were both dead. Had he carried on with his escape plan, Caesarion might have survived, but his tutor suggested that Octavian would take pity on the orphan. (Follow the search for Cleopatra’s true face and burial place.)

Indeed, Octavian had considered sparing the young man’s life. One of his confidants convinced him otherwise; it was inappropriate, he said, for there to be “too many Caesars.” So when Caesarion arrived in Alexandria to meet Octavian in August 30 B.C., he was immediately executed. The dream of a Roman-Egyptian pharaoh vanished, and the ancient Ptolemaic kingdom of Egypt died with Caesarion.

The children's fates

After he had their brother Caesarion executed, Octavian took Cleopatra’s three other children (all by Mark Antony) back with him to Rome where Octavian presented them in chains to the Roman people and paraded them through the streets in triumphal procession. Some sources say Octavian wished to execute them after the triumph, but that Octavia the Younger, his elder sister and the late Mark Antony’s ex-wife, convinced him to let her raise them alongside her own children.

The fate of the two boys is unknown. None of the popular historians of the time mention either Alexander Helios or Ptolemy Philadelphus again, which leads many to believe they died in childhood. Cleopatra Selene did survive; she married Juba II, king of Numidia and then Mauritania, and had several children with him.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Fireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state parkFireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state park

- These are the weird reasons octopuses change shape and colorThese are the weird reasons octopuses change shape and color

- Why young scientists want you to care about 'scary' speciesWhy young scientists want you to care about 'scary' species

- What rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlifeWhat rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlife

- He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?

Environment

- What rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlifeWhat rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlife

- He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?

- The northernmost flower living at the top of the worldThe northernmost flower living at the top of the world

- This beautiful floating flower is wreaking havoc on NigeriaThis beautiful floating flower is wreaking havoc on Nigeria

- What the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disasterWhat the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disaster

History & Culture

- Scientists find evidence of ancient waterway beside Egypt’s pyramidsScientists find evidence of ancient waterway beside Egypt’s pyramids

- This thriving society vanished into thin air. What happened?This thriving society vanished into thin air. What happened?

Science

- Why pickleball is so good for your body and your mindWhy pickleball is so good for your body and your mind

- Extreme heat can be deadly – here’s how to know if you’re at riskExtreme heat can be deadly – here’s how to know if you’re at risk

- Why dopamine drives you to do hard things—even without a rewardWhy dopamine drives you to do hard things—even without a reward

- What will astronauts use to drive across the Moon?What will astronauts use to drive across the Moon?

- Oral contraceptives may help lower the risk of sports injuriesOral contraceptives may help lower the risk of sports injuries

- How stressed are you? Answer these 10 questions to find out.

- Science

How stressed are you? Answer these 10 questions to find out.

Travel

- Fireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state parkFireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state park

- How to explore the highlights of Italy's dazzling Lake ComoHow to explore the highlights of Italy's dazzling Lake Como

- Going on a cruise? Here’s how to stay healthy onboardGoing on a cruise? Here’s how to stay healthy onboard

- What to see and do in Werfen, Austria's iconic destinationWhat to see and do in Werfen, Austria's iconic destination