1. Roxy Music – Ladytron

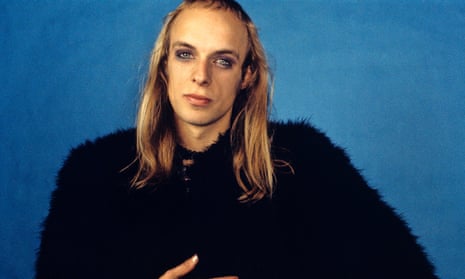

The Brian Eno of 2017 is, once again, the artfully bespectacled Wise Man of Ambient, having released his beautiful new album Reflection on New Year’s Day. That version of the man makes it harder to remember the wild feather-boa-flaunter of Roxy Music, who used analogue electronics to light a rocket up the rear of their preternaturally postmodern, wham-bam-glam rock’n’roll. Nowhere better can we find this whirling dervish than in 1972’s Ladytron, where Eno spends the first 60 seconds fiddling with bandmate Andy McKay’s VCS3 synthesiser, and creating whirlwinds out of tape echo. (Eno had been asked by Bryan Ferry to make some sounds that called to mind the moon landings.) The minor-key melody that leads us into the song proper has a signature Eno melancholy to it, already hinting towards the less manic, moving musician he would become. Still, the last 40 seconds show how brilliant being bonkers with oscillators can be.

2. Needles in the Camel’s Eye

It’s also instructive to remember Eno the solo artist before the accident that led him to listening to quieter music, which ultimately spirited his solo musical interests away from noisier territories. (I say solo, because Eno’s two LPs with David Byrne are neither quiet nor reflective, while Eno’s production work with mega-bands such as U2 and Coldplay aren’t afraid to pump up the volume.) Eno’s first two solo albums, Here Come the Warm Jets and Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy), are fantastic curios of their time, littered with awkward but glorious examples of art rock. In tracks such as Blank Frank and Put a Straw Under Baby, Eno is influenced by Syd Barrett in his singing style and off-the-wall lyrics, but the music throughout is often brighter and rockier. His debut album opener is a particular riot, all discordant, thrashing guitars and stop-start wham-bang.

3. The Big Ship

Gentler moments were part of Eno’s world right from the start of his solo career: for unsullied loveliness, try On Some Faraway Beach from Here Come the Warm Jets, or Taking Tiger Mountain’s title track. The year things got properly peaceful, however, was 1975. In January, on the way home from a production session, Eno slipped on a rainy pavement in London into the path of a speeding taxi. He was given an album of 18th-century harp music by his then girlfriend to aid his recovery. Incapacitated one day in bed, he put the record on too quietly but couldn’t turn it up, so its sounds became part of the general ambience of the room, at the same sound level as the falling rain. Mesmerised by this effect, Eno was determined to create it later himself. Discreet Music came out that November, but September’s Another Green World also had tracks that took us into softer, smaller places. The Big Ship is the best, sailing us off divinely, delicately, letting us float with the water.

4. Harmonia and Eno ’76 – Welcome

In September 1976, Eno pitched up at Harmonia’s studio in Germany for one of his most notable ambient collaborations. He’d already done two fantastic records with King Crimson’s Robert Fripp (1973’s No Pussyfooting and 1975’s Evening Star), but this project took him to the country where electronic music was quietly creating a new national soundtrack. Welcome is undeniably Eno from the off: the sweepingly sad, longing theme lulling listeners into the track, and then the whole album, has all his hallmarks. These sessions weren’t released at the time – Rykodisc finally put them out in 1997 – but Eno’s work with the band’s members continued. In 1977, Michael Rother departed, and Dieter Moebius and Roedelius regrouped as Cluster, recording the similarly softly spectacular Cluster & Eno album with their British friend.

5. David Bowie – Warszawa

In January 1977, the music Eno is arguably best known for was released: Warszawa, the first track from the second side of David Bowie’s Low. Eno wrote and arranged the sublime, sinister instrumental backing that makes it what it is, the main theme inspired by a figure of three consecutive notes that Tony Visconti and Mary Hopkin’s four-year-old son Delaney kept playing on the studio piano. Bowie was away at the time, attending a court case against his former manager, Michael Lippman, but on returning, heard the track, adored it, and sang his wordless, affecting melodies on top of them, inspired by a children’s choir he’d heard in the Polish capital city. Not long after, Eno told Mary Harron of Punk Magazine about the composition excitedly. “I wrote all the music for one of the numbers … it’s a very good number: I think it’s a new direction for [Bowie]. And me. A very slow, melancholy piece that’s rather like a kind of folk orchestra. An Eastern European folk orchestra.” Years later, he told Andy Gill of Mojo how brilliantly Bowie could adapt himself to the material presented to him: “[Bowie] picks up the mood of a musical landscape, such as the type I might make, and he can really bring it to a sharp focus, both with the words he uses and the style of singing he chooses.”

6. Julie With …

In December 1977, Eno released Before and After Science, most of which bursts with a shuddering, juddering nervous energy. Tracks such as Kurt’s Rejoinder and King’s Lead Hat (an anagram of Talking Heads, a band he was also producing at the time) remind us of the Eno of earlier in the decade, with added punky spirit thrown in. Julie With … is slower, more sombre, more densely romantic. Eno sings here, softer than before, telling us the story of someone being at sea with a girl wearing an open blouse, looking at the sky. The water is blue and dark as they drift into abandonment, in all senses: “No wind disturbs our coloured sail / The radio is silent, so are we.”

7. An Ending (Ascent)

Ambient 1: Music for Airports was released in 1978, inspired by Eno’s experience of being forced to listen to bad disco music in a futuristic airport in Cologne, one designed (naturally) by the father of Florian Schneider from Kraftwerk. Four Ambient albums were released in total, then in 1983 came Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks, recorded for a documentary about the US moon missions, For All Mankind. An Ending is one of Eno’s crowning achievements as a musician: its rapturously beautiful, innocent melody being deceptively simple in both composition and delivery, its soft high notes (played on the then new and later ubiquitous 80s keyboard the Yamaha DX7) truly sounding as if they’re coming from the great beyond. Burial sampled it brilliantly on his 2006 debut album, for the track Forgive.

8. Thursday Afternoon

In sound, this 60-minute composition is very much the child of Ambient 1: Music for Airports’ 1/1, a track based on a looped figure played on the piano by Robert Wyatt. Thursday Afternoon was written in 1985 to accompany a series of video paintings, which change slowly and imperceptibly for the viewer, much like its soundtrack. This is one of many pieces that writers have told Eno aids their writing, which fits his idea of his ambient music being functional. As he told Jarvis Cocker on a (very much recommended) New Year’s Day ambient special on BBC Radio 6Music: “[I like] this idea of making music to do something, to help people in some way, to make an atmosphere that was useful for them, and then over the years the thing I thought I most want an atmosphere for is to help my mind … to make a mental place I can go to and rely on to focus me in some way.”

9. Eno and Hyde – Cells & Bells

The last decade has seen more interesting collaborations from Eno, including two albums with producer Jon Hopkins and two in 2014 with Underworld frontman Karl Hyde. This absorbing track closed Eno and Hyde’s second record together, driven by sounds that tremble between states of anxiety and calm, with Hyde’s surreal wordplay painting pictures of cities, building blocks, waiting and failure. A mood is struck, a sense is captured, and it snags deep under the skin.

10. Fickle Sun (iii) I’m Set Free

Last year’s Eno album The Ship treated us to the sound of the then 67-year-old’s older, lower voice, processed eerily and powerfully on the strange, poetic title track, but left to sound simple, deep and sweet for the album’s final flourish. This is a cover of the Velvet Underground’s I’m Set Free. (He famously said in a 1982 interview that hardly anyone bought the Velvet Underground’s debut album “but everyone who bought one … started a band”.) Eno slows the song down in tempo, but plays up its beauty, building a chorus of voices and strings as he pushes it towards its climax. Then it quietly retreats, as Eno always does, leaving its mood behind in the memory, lingering on.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion