Brian Eno’s new album is called Reflection, and what better time to reflect on an astonishing career? Or careers. There’s the first incarnation of Eno as the leopardskin-shirted synth-twiddler who overshadowed the more obviously mannered Bryan Ferry in Roxy Music. With his shoulder-length hair and androgynous beauty, there was something otherworldly about Eno. He was as preposterous as he was cool. So cool that, back then, he didn’t bother with a first name.

After two wonderfully adventurous albums he left and Roxy became more conventional. There followed a sustained solo career, starting with the more poppy Here Come the Warm Jets, progressing to the defiant obscurity of his ambient albums and on to commercial Eno, the revered producer behind many of the great Bowie, Talking Heads, U2 and Coldplay records.

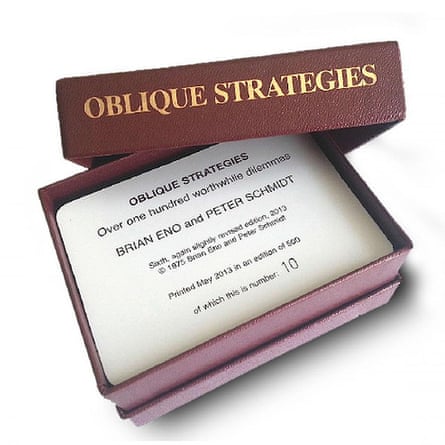

There is Eno the visionary, who helped conceive a 10,000-year clock and invented an influential pack of cards called Oblique Strategies that offer creative solutions for people in a pickle. There is Eno the visual artist; Eno the activist, tirelessly campaigning for a fairer world; and Eno the philosopher, endlessly thinking of ways in which to bring this new world about.

We meet at his studio, near Notting Hill in west London. It is a mix of the minimalist and maximalist. Minimalist in its big white empty spaces, maximalist in the numerous books carefully filed away (library-like sections for African, Asian and European art), old-fashioned hi-fi equipment, a parked bike, and his own Rothko-ish artworks.

Eno, now 68, could not look more different from the louche glamour-puss of the early 70s. As his music became more pared down, so did he. The head was shaved, the makeup washed off and the feather boa dispensed with. Nowadays, he looks like a stylish academic.

His assistant asks me to join Eno at his table. “I’ll just be 40 seconds, finishing off my lunch,” Eno says. He takes a mouthful of fruit salad. “Just 30 seconds now.” There has always been something fastidious about him. His interviews tend to be 45 minutes long precisely. One journalist said that Eno had interrupted their chat to play him an Elvis Presley record that lasted two minutes and seven seconds, and then added two minutes and seven seconds to the interview so the journalist wouldn’t be shortchanged. At the same time, Eno loves to embrace the random. As a producer, he encourages artists to pick up Oblique Strategies cards to alter the path they are taking. I tell him I have brought a pack with me in case we find ourselves struggling. He smiles, flashing a gold tooth. “That will be just the job, I should think,” he says.

Eno talks slowly, calmly, eloquently. He would be brilliant on Just a Minute – no repetition, hesitation or deviation. His voice is as soothing as his ambient music. His full name is Brian Peter George St John le Baptiste de la Salle Eno (the St John le Baptiste de la Salle was added at confirmation). You might assume he was an aristocrat, but his father and grandfather were postmen. “And my great grandad actually,” he says enthusiastically when I mention it. “And my two uncles.”

Did he ever think that was his destiny? “Well, I did go into communications, didn’t I?” He laughs. You’re a sonic postman? “Yeah! I help people communicate with each other in one way or another. When I was in my mid-30s, and my mother and father were living in a house I had bought for them with the proceeds of my music, my mum said: ‘Dad and I were talking. Do you think you’ll ever settle down and get a job?’ Hahahhaha! She said: ‘You could get a job in the Post Office.’ In the office! You know, not trudging delivering mail.”

Eno decided he didn’t want a regular job when he saw the effect it had on his father. “He did shift work. It was a three-week cycle, mornings, afternoons and nights. I realised years later he was in a permanent state of jet lag because his eight-hour work day was shifting every week. I remember him coming home from work and sitting at the table; my mother had just put the food down and he fell forward, asleep. I thought even if I have to turn to crime, I won’t get a job; the horror of being that exhausted and doing your work just to keep things going; the lack of freedom in your life.”

His Belgian mother had spent the war in Germany building planes in a labour camp. Eventually she returned to Belgium at the end of the war. “It took her three months to get back. She arrived in Dendermonde near Brussels weighing five stone.”

He has been talking quietly and beautifully about his parents. So it comes as a shock when I ask where his string of first names comes from, and he explodes. “God, are we going to do any interesting questions? This is all bollocks. I mean I’m not fucking interested at all in me. I want to talk about ideas. Can we do any of that?”

He picks up one of the Oblique Strategy cards, and bursts out laughing. He shows it to the two women in the studio. “Hahaha! How about that? Hahahaha! ‘Take a break!’”

“Take a break,” they echo. “Hahaha!”

“Aren’t they brilliant?” Eno says. “Fancy that.”

The more they laugh, the smaller I feel.

Eno says he hates talking about himself. “I’m not interested in that personality aspect of being an artist. It’s all based on the idea that artists are automatically interesting people. I can tell you they aren’t. Their art might be very interesting, but as people they are no more or less interesting than anybody else. And I’m really not at all interested in talking about Brian Eno. His ideas, however, I think have something to recommend them.”

So what is Brian Eno working on at the moment, I ask. “I’m interested in the idea of generative music as a sort of model for how society or politics could work. I’m working out the ideas I’m interested in, about how you make a working society rather than a dysfunctional one like the one we live in at the moment – by trying to make music in a new way. I’m trying to see what kinds of models and and structures make the music I want to hear, and then I’m finding it’s not a bad idea to try to think about making societies in that way.”

Could he be more specific? “Yes. If you think of the classical picture of how things were organised in an orchestra – where you have the composer, conductor, leader of the orchestra, section principals, section sub principals, rank and file – the flow of information is always downwards. The guy at the bottom doesn’t get to talk to that guy at the top. Almost none of us now would think that hierarchic model of social organisation, the pyramid, is a good way to arrange things.”

In other words, he says, society should be built on the more egalitarian model of a folk or rock band, who just get together and do their thing, rather than a classical orchestra. “Can’t you see,” he says with the passion of a visionary, “if you transpose that argument into social terms, it’s the argument between the top down and bottom up? It is possible to have a society that doesn’t have pre-existing rules and structures. And you can use the social structures of bands, theatre groups, dance groups, all the things we now call culture. You can say: ‘Well, it works here. Why shouldn’t it work elsewhere?’”

He has called himself an optimist. In the past. I ask him if he still is, post-2016. Yes, he says, there is a positive way to look at it. “Most people I know felt that 2016 was the beginning of a long decline with Brexit, then Trump and all these nationalist movements in Europe. It looked like things were going to get worse and worse. I said: ‘Well, what about thinking about it in a different way?’ Actually, it’s the end of a long decline. We’ve been in decline for about 40 years since Thatcher and Reagan and the Ayn Rand infection spread through the political class, and perhaps we’ve bottomed out. My feeling about Brexit was not anger at anybody else, it was anger at myself for not realising what was going on. I thought that all those Ukip people and those National Fronty people were in a little bubble. Then I thought: ‘Fuck, it was us, we were in the bubble, we didn’t notice it.’ There was a revolution brewing and we didn’t spot it because we didn’t make it. We expected we were going to be the revolution.”

He draws me a little diagram to explain how society has changed – productivity and real wages rising in tandem till 1975, then productivity continuing to rise while real wages fell. “It is easily summarised in that Joseph Stiglitz graph.” The trouble now, he says, is the extremes of wealth and poverty. “You have 62 people worth the amount the bottom three and a half billion people are worth. Sixty-two people! You could put them all in one bloody bus … then crash it!” He grins. “Don’t say that bit.” (Since we meet, Oxfam publish a report suggesting that only eight men own as much wealth as the poorest 3.6 billion people in the world – half the world’s population.)

Eno himself is a multimillionaire, largely because of his work as a producer.He wouldn’t be one of the 62, would he, I ask. “I certainly wouldn’t be,” he says with a thin smile. “No, I’m a long way off that.”

He is still thinking about the political fallout of the past year. “Actually, in retrospect, I’ve started to think I’m pleased about Trump and I’m pleased about Brexit because it gives us a kick up the arse and we needed it because we weren’t going to change anything. Just imagine if Hillary Clinton had won and we’d been business as usual, the whole structure she’d inherited, the whole Clinton family myth. I don’t know that’s a future I would particularly want. It just seems that was grinding slowly to a halt, whereas now, with Trump, there’s a chance of a proper crash, and a chance to really rethink.”

Reflection is his 26th solo album, and his first ambient release in five years. Does he think there is a particular need for its soothing qualities at the moment? “Well, I think this is quite a good time for it,” he says.

I am not sure I get ambient – it’s pleasant but dull; nice to have on in the background while you are working. “That’s exactly what I want it for myself,” he says, delighted. “I do a lot of writing, and one of the ways I have of writing is by starting to make a piece of music of that kind and then, while I’m carrying on writing, I’m thinking: ‘There’s a bit too much of that and not enough of this.’ So I go in and fiddle around with it a bit. I keep adjusting the music until it’s helping the writing, and then I adjust it less and less.”

I had read that he initially made ambient music to help him when travelling, because he was frightened of flying; that it was supposed to be a kind of audio Mogadon. “No, not Mogadon. One of the things you can get from music is surrender. From a lot of art, what you’re saying is: ‘Let it happen to me. I’m going to let myself be out of control. I’m going to let something else take over me.’” And that’s what he wants to happen with this music.

That desire to surrender is interesting because, in many ways, he seems so controlled. I mention the interview with the Elvis song. “Well, that’s fair, isn’t it? It’s controlled but not controlling. You asked me whether I’m controlling. That’s different to whether I’m controlled. I think controlling would be if I said to the interviewer: ‘I’m taking some time out of the interview to play you something, but fuck you, I’m in control here, so piss off.’ I didn’t say that. I said I’m taking some time out of the interview to play you something, but since you didn’t request that, I’m not expecting you to lose that time. Of course, I work in a role that could be seen as a controlling role as a producer. But, in fact, I’m not that kind of producer. What I want to do is make situations where we’re all slightly at sea because people make their best work when they are alert, and alertness comes at the moment when you feel you’re on the edge of being out of control. You’re not alert when you’re settled and you know exactly what you’re doing.”

Ah, the collaborations. Much as I admire Eno the thinker and activist, like most of his fans it is Eno the collaborator/producer I love. And this is what I have really been looking forward to talking about. Like many middle-aged pop enthusiasts, I owe a huge debt to Eno. He has shaped so much of my favourite music – from the first two Roxy Music albums, to Bowie’s Berlin trilogy and Talking Heads’ Remain in Light. Just as fascinating is his ability to mentor the more obviously commercial Coldplay and U2.

Who has he enjoyed working with most? Pause. “Probably Brian Eno! Hehehe! I keep returning to him.” No, really, I say, which collaborations does he look back on with most satisfaction? “I don’t look back much, to be honest. Whenever I look back at music, I think how I could have done it better.”

Is there nothing that makes him think, ‘God, I love that’? “Well, I suppose every collaboration continued because I liked doing it. Some of them are funnier than others …”

Which ones? “Erm … Uch. I don’t want to talk about this. I so don’t want to talk about this.” And again, an explosion. “Look, we’ve got a few minutes left. Let’s talk about something good.”

That’s controlling, I say.

“It’s not controlling. It’s just fucking boring. I have to keep myself awake. I’m tired.”

I don’t understand, I say – I don’t even know what is so “fucking boring” that you are refusing to talk about.

“I just don’t want to talk about history. All that shit! You can find all this in other interviews I’ve done. I’ve been 40 years talking about other people I’ve worked with. No, sorry. I’m just not interested.”

Doesn’t he think the idea that the interview should be entirely about the present and what he may do in the future is a bit unreasonable?

“But you can do research,” he says. And calm, measured Eno has turned into irascible Eno. “That’s your job! Research! You can look through thousands of interviews I’ve done where I’ve talked about all of this. That’s your job! You get paid for it. I don’t get paid for this, by the way!”

I get paid to ask people questions, I say.

“OK, well, you’ve asked me and I’ve said I don’t want to answer them. That’s a fair deal, isn’t it? I know what you were after,” he says, “and I don’t want to go there. I don’t want to go into a historical gloss on my career because that is not where my thoughts are right now. I’m thinking about something as we’re talking that we’re not talking about and I don’t want to lose it.”

What is he thinking about? “That piece of music I’m working on in there which I have been playing today and making changes to in between interviews.”

Was he thinking that I was asking about Bowie?

“I know you were.”

Well, I kind of was and wasn’t.

“Well, you kind of were,” he mocks.

No, I say, I was thinking of any number of the great collaborations, including Bowie.

“I’m not interested in talking about any of them. And I think it would be considerate of you to say: ‘He doesn’t want to talk about that, so there are plenty of other things he could talk about; he’s quite an interesting guy.’” Then he tells me exactly how I’m trying to trap him. “‘I could ask him a million other questions, but I know because this would make a headline, so I’m going to fucking ask him about that.’”

I think that’s unfair, I say.

“All right, sorry, that is unfair,” Eno says.

We’ve spent most of the time talking about politics.

“Only because I asked you to,” he replies sullenly.

“OK, we’re going to have to have to wrap this up now,” the publicist says.

“I don’t want to wrap it up on a bad vibe,” Eno says, talking fast and breathing heavily.

But we’ve ground to a halt. I’m not sure that even his Oblique Strategies could help us now.

“I’m sorry,” he says. “I’m very tired today because I didn’t sleep last night. And I knew I was going to be ratty, so I’m sorry about that. But I really don’t want to spend the rest of my life – I’m now 68, so I might have another 15 to 20 years left – talking about my history. So, given the little time I’ve got left on this planet, I would really love to focus on some of the new things I’m doing.”

What new stuff have we not talked about that he would like to talk about, I ask. Silence. I point to the serene orange lightbox image in front of us, and ask if that’s a recent piece of work. “Yes, that’s one of my new pieces. Yes, this is stuff I’ve been doing for hospitals,” he says. “I was invited to make some of these for rooms where people are spending a long time in stressful situations.” With that he calls the interview to an end.

Reflection is out now on Warp.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion