Of all the many faces of Martin Luther King that will be invoked this week as America marks the 50th anniversary of his assassination – King the orator of the mountaintop speech, King the non-violent protester marching towards Montgomery, King the visionary with the dream of justice rolling down like a mighty stream – the most tender is the Martin Luther King of the kissing game.

He would play it with his wife Coretta and four young children whenever he got back to the family home in Atlanta, Georgia, after long days and nights on the civil rights trail. Having braved police batons and attack dogs across the deep south, he would finally turn into the drive of what was to be his last home in Sunset Avenue, where he would be met by a little girl rushing towards him and leaping into his arms.

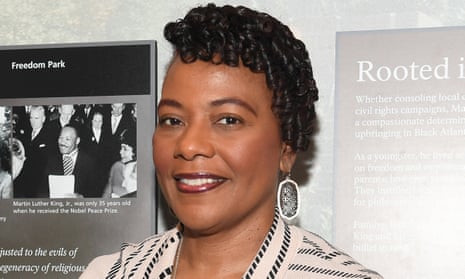

“Today we’re going to play the kissing game,” King would say to Bernice, his youngest child, as she clung to him. Then he would point to a special place on his face and invite her to kiss it.

“He called it a ‘sugar spot’,” Bernice says. “We each had one – mummy’s sugar spot was, of course, in the middle of the lips; my two brothers’ were on either cheek; my late sister Yolanda’s was off the corner of the mouth.”

Bernice’s sugar spot was on his forehead.

In the public world of Dr Martin Luther King Jr, Bernice and her siblings – Yolanda, who died in 2007, Martin and Dexter – are forever associated with the famous line in his 1963 speech at the March on Washington: “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

In the private world of the King family, however, and for Bernice in particular, who was so young when her father was untimely ripped from her, there are only slivers of memory. Shards of recollection, some her own, some handed to her by her older relatives.

She recalls very little of that day, 4 April 1968. It was a week after her fifth birthday, and when the TV networks began to carry news that her father had been shot in Memphis she was drifting off to sleep.

She has only a pointillist picture of what happened next, the days and weeks of noise and hurt, disjointedly composed out of tiny dots of memory. It was Dexter who recalled the babysitter falling backwards and exclaiming “Oh my God!” when, they surmised later, she was informed that the bullet that pierced their father’s neck as he stood on the balcony of the Lorraine motel had taken his life.

Confusion. That was Bernice’s main recollection. Not the confusion of the adults that in turn morphed into anger that set rioting ablaze across the nation. But the confusion of a child for whom none of this made any sense.

As the family was boarding the plane that would take them to Memphis, to her father’s body lying in the casket, Coretta told Bernice that he was dead and that he wouldn’t be able to speak to her any more as his “spirit has gone on to live with God”. The child heard a hissing noise at the back of the plane which she knows now must have been the plane’s engines, but back then it sounded to her just like daddy.

“I said, ‘Well, he’s breathing, I hear him breathing in the back’. And she said, ‘No’.”

At the funeral service at the Ebenezer Baptist church, at Coretta’s request they played the recording of King’s famous Drum Major Instinct sermon, the last he gave in that same place. As her father’s taped voice could be heard echoing around the congregation, eerily describing the funeral that he wished to be given – “If you want to say that I was a drum major, say that I was a drum major for justice” – she couldn’t make sense of that either.

“I guess my mother didn’t realize that she didn’t prepare me, because she told me earlier he wouldn’t be able to speak to me, and yet I hear his voice booming out of the speakers and I’m looking around wondering where is he. I remember that very well.”

Bernice King has spent a good deal of the past 50 years trying to comprehend that moment in which her father was taken from her. It’s been a personal journey that strikingly matches the public journey that America has pursued as it tries to make sense of what it did to one of its most cherished sons.

For many years she pushed the thoughts of her father away, wrestling with her own bouts of anger until in her late teens and early 20s she found her way back to him. She was called to the ministry, and in time made his life’s mission fighting for justice and equality her own.

Over the half-century since his death she has managed to avoid most of the ugliness that has enveloped her brothers as a result of their controversial money-oriented handling of King’s estate. Instead she has focused her energies on the struggle against South African apartheid, police brutality in the US and the war on poverty – in short she has grown into the nearest personification that exists of keeper of the Martin Luther King flame.

Which makes her a very good person to ask, in the course of a Guardian interview for the 50th anniversary, how she sees the threat to her father’s legacy emanating from the current White House and from Republican-controlled state legislatures across the country.

At a time when voting rights are under unparalleled attack; when inequality and poverty are deepening, especially for African Americans; and when even measures to combat racial segregation are being rolled back, isn’t she fearful that everything she and her father have struggled for is on the chopping block?

King is having none of it.

“I guess I don’t look at it the way other people do,” she says, using the word “it” to stand in for another that begins with a T and ends in a P. “I look at it as a wonderful moment. Here we have people being galvanized all over this nation, and even the world, who are speaking up in ways perhaps they never have.”

Warming to her theme, she insists that the challenges of the past 15 months have further strengthened King’s legacy, not diminished it. “Sure, our country is faced with some serious issues, but that makes protest and free speech all the more critical now. Now you see people standing in the tradition of Martin Luther King Jr and saying this is an injustice, enough is enough, we are going to resist.”

She adds: “I don’t see it as a threat, but as an opportunity to complete some of the work he did not get to complete himself.”

Her point was made for her last month at the March for Our Lives in Washington. There was the moment when her niece, nine-year-old Yolanda Renee King, spoke so movingly about her dream of a gun-free world.

But more importantly there was the spectacle of hundreds of thousands of kids, led by the student survivors of the massacre at Marjory Stoneman Douglas high school, coming together to demand that their inert and corrupted political representatives do something to combat gun violence.

What could be more in the spirit of MLK than that?

“Something big is going on,” King says. “I’m talking about a society that refuses to allow injustice just to persist without making our voices heard and without organizing to bring about effective change through our voting system.”

She was particularly struck at the march, which she attended in Washington, to see young people assiduously registering other young people to vote. In her analysis, that is the first indication that the apathy that has set in among young Americans – youth turnout in the 2014 midterm elections was the lowest in 40 years – may be about to change.

“The best way to sum it up is what my mother said, which is that struggle is a never-ending process, freedom is never really won – you earn it and win it in every generation. In my personal opinion this most recent generation has been in danger of not making their contribution to the freedom struggle.”

That’s a severe charge to be levelled at an entire generation, especially coming from the daughter of Martin Luther King: young Americans are failing in their epochal duties. But she quickly sweetens the accusation with a message of hope.

“Now there is an opportunity for them to make their contribution to the freedom struggle, to tackle what Daddy called the triple evils of poverty, racism and militarism. It’s coming back again, with strength and fervor.”

There’s no holding King back now. There is inherited fire in her belly that is very much alight.

“This nation is awoke, there is a new, different kind of vigilance that we haven’t seen in the past 25 years,” she says. “In the end I still have the same hope as my father – that unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the last word.”