Most of you probably did not read about Bayard Rustin in school, the former US president Barack Obama observed at a recent film screening in Washington DC. Why? Rustin lived openly and unapologetically gay in the 1950s.

“Imagine that, think about that,” Obama implored an audience at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. “This is someone who was courageous enough to be who he was despite the fact that he was most certainly going to be ostracised, fired from jobs, pushed aside. And that’s what happened most of the time.”

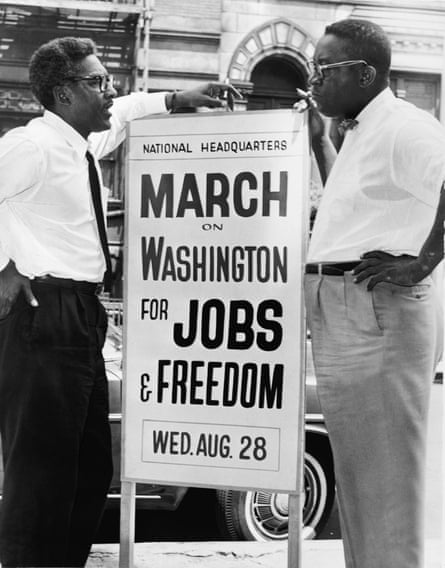

The civil rights organiser and pacifist Rustin is the subject of the first narrative feature from Barack and Michelle Obama’s production company, Higher Ground. Entitled Rustin and streaming on Netflix, the movie chronicles the run-up to the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, during which Martin Luther King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech.

The film, starring Colman Domingo and directed by George C Wolfe, is a portrait of grassroots activism and the long-neglected Rustin, who faces prejudice from some civil rights leaders but insists: “On the day that I was born Black, I was also born homosexual. They either believe in freedom or justice for all, or they do not.”

Born in West Chester, Pennsylvania, in 1912, Rustin was a staunch proponent of peaceful protest, in part due to his Quaker upbringing, and helped introduce the Gandhian concept of nonviolent resistance. He was a key adviser to King during the Montgomery bus boycott and among the organisers of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

As a gay man, Rustin was forced to live with the constraints and prejudices of the time, including beatings and arrests. In 1953 he spent 50 days in jail and was registered as a sex offender after being discovered having sex in a parked car in Pasadena, California (he was posthumously pardoned). But he refused to hide his sexuality.

John D’Emilio, author of Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin, says: “The 1940s and 1950s and 1960s can be reasonably described as the most openly homophobic in US history, where the oppression of LGBTQ people is at its height and virtually everyone who had those identities was silent and hidden about it. People would lead what were described as double lives or wear a mask and pretend to be heterosexual or gender-conforming.

“Rustin never pretended to be heterosexual. If an organisation or a network that he was a part of was having a big social event or a reception and he had a boyfriend at the time, he would come with his boyfriend and he didn’t name it, but it was obvious to the people who were close to him and worked with him that he was gay.”

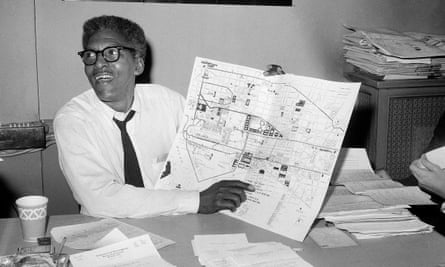

When it came to fulfilling the vision of the Black labour leader A Philip Randolph for a march on Washington 60 years ago this summer, Rustin had the support of both Randolph and King but would have to overcome the homophobia of some civil rights leaders who feared that he would set back their cause.

Clarence B Jones, a lawyer and speechwriter for King, recalls: “A Philip Randolph, Dr King and myself and a couple of other people recognised that we had an uphill battle because there was a group of Black conservative clergymen who were opposed to Bayard having a very important leadership role because of his being gay and because of the sodomy conviction.”

Jones, Randolph, King and labour leaders “meticulously plotted” how to outmanoeuvre their conservative opponents and ensure Rustin got the job. Jones deployed his in-depth knowledge of Robert’s Rules of Order, a respected guide to parliamentary and organisation procedure.

Speaking by phone from his home in Palo Alto, California, Jones, 92, continues: “This is the kind of discussion we had: we neither have the time nor the likelihood to convince people who are opposed to Bayard because of his homosexuality. We don’t practically have the time allotted to us to try to persuade them of our point of view. What we have to do is to put a procedure in place that will prevent them from blocking what we want them to do.

“I said Bayard, you’re blessed that I have an encyclopedic knowledge of Robert’s Rules of Order. You don’t have to persuade me how good you are – I already know that – and you have the love and support of the two greatest civil rights leaders walking the earth, A Philip Randolph and Martin Luther King Jr. I am the heavy. I speak for them. Although they’ll be there speaking, I will say things in a way that they cannot say it because they have to be more diplomatic. But I don’t have to be diplomatic.”

Jones had further advice for the famously loquacious Rustin before the crunch meeting that would decide the fate of the march: “The one thing you have to do is keep your goddam mouth shut. It is not for you to utter one word of your qualifications in defence. Does that make sense? It’s very simple: if I want somebody to be impressed with my credentials, I don’t do it. I have Martin Luther King speak on my behalf. The best thing you can do is keep quiet. You don’t have to say a damn thing.”

Jones recalls how some distinguished figures who had dedicated their lives to racial equality had a blind spot when it came to sexuality. “Now, what is really sad is that you had these negro ministers and a couple of negro labour leaders who, on the one hand, would talk to you about how dedicated they are and, if you look at their background, you see the credentials of their struggle in the civil rights movement.

“They were willing to set all of that aside because they couldn’t get over the fact that someone whom they objectively knew was capable – it was hard for them to deal with the reality that he was homosexual.

“I had to say, how does it affect you? Why are you upset? Bayard isn’t coming on to you, is he? We’re talking about getting the best organisational mind available. I mean, that’s like saying to me I drink three or four martinis a day. What, you’re not going to think I’m a good lawyer because I drink three or four martinis a day? Get over it.”

When it came to sit down with the march organising committee, a rival name was proposed for the executive director position, Jones says. Rustin’s name was also put forward. There was an opportunity to attendees to voice their support for each candidate. Jones then “called the question”, effectively asking for the vote.

“By prearrangement, the ayes [for Rustin], they shouted it, the volume was over the top. To avoid any reconsideration, I then said, ‘The ayes have it. The question is closed. Bayard Rustin has been selected as the executive director. Move for reconsideration – out of order. Question closed. Mr Rustin, you are now executive director.’ We literally jammed it through.

“That, among other things was the best possible thing that could ever have happened to the March on Washington. There is no question in my mind that the march would have taken place but there is also no question in my mind that the degree that it took place and it was as successful as it was was directly related to the organisational skills of Bayard Rustin.”

Rustin pulled together a legion of young activists to plan the march, get demonstrators on to buses and trains and ensure that the event remained peaceful. It drew a quarter of a million people, including film stars and musicians, and is widely credited with pressuring the John F Kennedy administration to act on civil rights, ultimately leading to the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

But Rustin was long denied the credit he deserves. Jones, who recently published a memoir, Last of the Lions, says he welcomes the new film for belatedly correcting the record. “Finally, after all this time, the organisational genius of the success of the March on Washington is being celebrated.

“Now, Bayard Rustin couldn’t preach like Martin Luther King Jr. He couldn’t sing like Peter, Paul and Mary or Bob Dylan. But there would have been nothing to sing about, there would have been nothing for Dr King to preach about if the march had not been successful in taking place. That is due to Bayard Rustin’s organisational leadership supported by the base of trade unions and church people that he so effectively organised to put the march on.”

Rustin went on to serve as president of the A Philip Randolph Institute, a civil rights organisation in New York, from 1966 to 1979. Later in life he turned his attention to LGBTQ+ activism and its intersection with the continuing civil rights struggle. He was the first to bring the Aids crisis to the attention of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People).

He also fell in love. In an interview for StoryCorps, Walter Naegle recalled meeting Rustin in 1977 while making his way to New York’s Times Square: “We were on the same corner waiting for the light to change. He had a wonderful shock of white hair. I guess he was of my parents’ generation, but we looked at each other and lightning struck.”

Now 74, Naegle, speaking from a hotel in Washington, where he was to attend the museum screening with the Obamas, recalls: “He was a presence. He was somebody who carried himself, he had wonderful posture and he had a great sense of style. He always dressed very beautifully and, of course, he usually had one of his walking sticks with him so that kind of set him apart.

“When he walked into a room, people paid attention and he was very engaging, very warm, had a wonderful sense of humour and made people feel comfortable around him. For all of those qualities, he was still very approachable and very easy to talk to. When he talked to you, he made you feel like you were the most important person in the room. He was not dismissive and not haughty or cold in any way.”

Marriage equality had not yet been achieved so Rustin legally adopted Naegle as a son to protect their rights and ensure that Naegle would inherit his estate. Naegle, a photographer based in New York who runs the Rustin Fund, continues: “Bayard certainly wasn’t uncomfortable with his sexuality; the society was uncomfortable with his sexuality.

“He never hid himself or was in the closet per se but it was certainly easier to walk around in the city, perhaps with his arm around me or holding hands, in the 70s and 80s than it would have been in the 50s and the 60s.”

According to Naegle, Rustin did not carry bitterness towards the civil rights activists who had discriminated against him. “He was fine. He knew who he was. He had a strong identity. He had tremendous support from the people that mattered most, namely A Philip Randolph, Alma Thomas, people like that. He wasn’t so concerned about other people and what they thought of him.”

The couple had been together for a decade when Rustin died suddenly and unexpectedly aged 75 in 1987. When he was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2013, Naegle received the honour on his behalf from Obama at the White House. He adds: “It was wonderful. It was thrilling. Certainly a good moment for Bayard be lifted up and recognised because all of the other people who had headed the March on Washington had gotten the medal.

“Dr King’s was, of course, awarded posthumously but everybody else had gotten it during their lifetime and this was another way of bringing Bayard into the fold, into the movement, giving him the credit that he deserved for organising that march because if it hadn’t been for him that march wouldn’t have happened.”

Naegle has no doubts that Rustin was denied the recognition he deserved during his lifetime. “It’s pretty easy to gauge it and understand why he hasn’t been acknowledged, certainly in textbooks and things like that,” he reflects. “But anybody who reads the really serious histories of the movement, Bayard’s fingerprints are all over it. You can’t avoid him, try as you might.

“People have been able to keep them out of textbooks for any number of reasons. Part of that is, how many people do they really know? They hear of Dr King, they hear of Malcolm X. How many people really know Jim Farmer or Whitney Young or even Mr Randolph? So it’s probably the way history is written but the film and recent books that have been published will certainly propel him to a different level, even higher visibility than the medal gave him, because Netflix is streamed all over the world. This will be an international recognition of his abilities and his life.”

What would Rustin make of the US today, swinging between the elections of Obama and Donald Trump? Naegle muses: “He would be pleased about the progress but he would be cautious and very wary about things we’ve been going through for the last couple of years and continue to go through.

“He wouldn’t be discouraged and depressed. He would be out there organising and challenging and trying to find a way to turn things back in the right direction. He understood that history is like a pendulum: it swings back and forth and you’re going to have some defeats but it doesn’t mean you give up and walk away. You just have to rethink your strategies and get out there and keep fighting.

“He would be encouraged and inspired and I hope that this film will do that because it doesn’t shy away from the challenges that Bayard had, occasionally being exiled from the movement, mostly because he was gay. But it shows him as a resilient figure and, in the end, a triumphant figure. The march was a great day in our country’s history. It was a triumph and it would not have happened without him.”

Rustin is now available on Netflix