Barcelona 1992: a city turning towards the sea and winning the hearts of the world

Thirty years ago, the Olympic Games Barcelona 1992 stunned the world with a magnificent Opening Ceremony and unforgettable sporting performances. But the impact of the Games went far beyond creating lasting memories for fans around the world. With the global exposure as the catalyst, Barcelona transformed into a metropolitan world city confidently listed among Europe’s top destinations.

Unforgettable moments

From the spectacular staging in the Catalan capital to the geopolitical backdrop, the Games of the XXV Olympiad were a landmark event, and the unity on display was especially poignant for the Olympic Movement.

Following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Games were boycott-free for the first time since 1972.

Germany sent a single delegation team, while Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania competed as independent National Olympic Committees (NOCs). Twelve former Soviet republics entered the Opening Ceremony as the Unified Team, under the Olympic flag.

Following the breakup of Yugoslavia in 1992, Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina competed as new NOCs, while athletes from Serbia, Montenegro and Moldova competed as independent Olympic participants under the Olympic flag and using the Olympic Anthem.

In an act of solidarity with the host of the Olympic Winter Games Sarajevo 1984, the city of Barcelona, its citizens and the Barcelona 1992 Organising Committee provided humanitarian aid to the people of Sarajevo, badly affected by the ongoing Yugoslavian war.

After finally ending apartheid, South Africa was welcomed back to the Olympic fold, having last competed in 1960. The Games were attended by Nelson Mandela – President of the African National Congress (ANC) at the time, leader of the anti-apartheid movement and a strong supporter of sport as a tool to contribute to a peaceful world.

The Opening Ceremony of the Barcelona Olympics was hailed as one of the most magnificent in sporting memory. From dancers performing Catalonia’s traditional circular Sardana dance, forming the Olympic rings, and José Carreras and Montserrat Caballé singing Freddie Mercury’s “Barcelona” anthem, to the dramatic lighting of the Olympic flame with an arrow shot over the heads of the crowd, the ceremony mirrored the host city’s rich spirit and striking transformation.

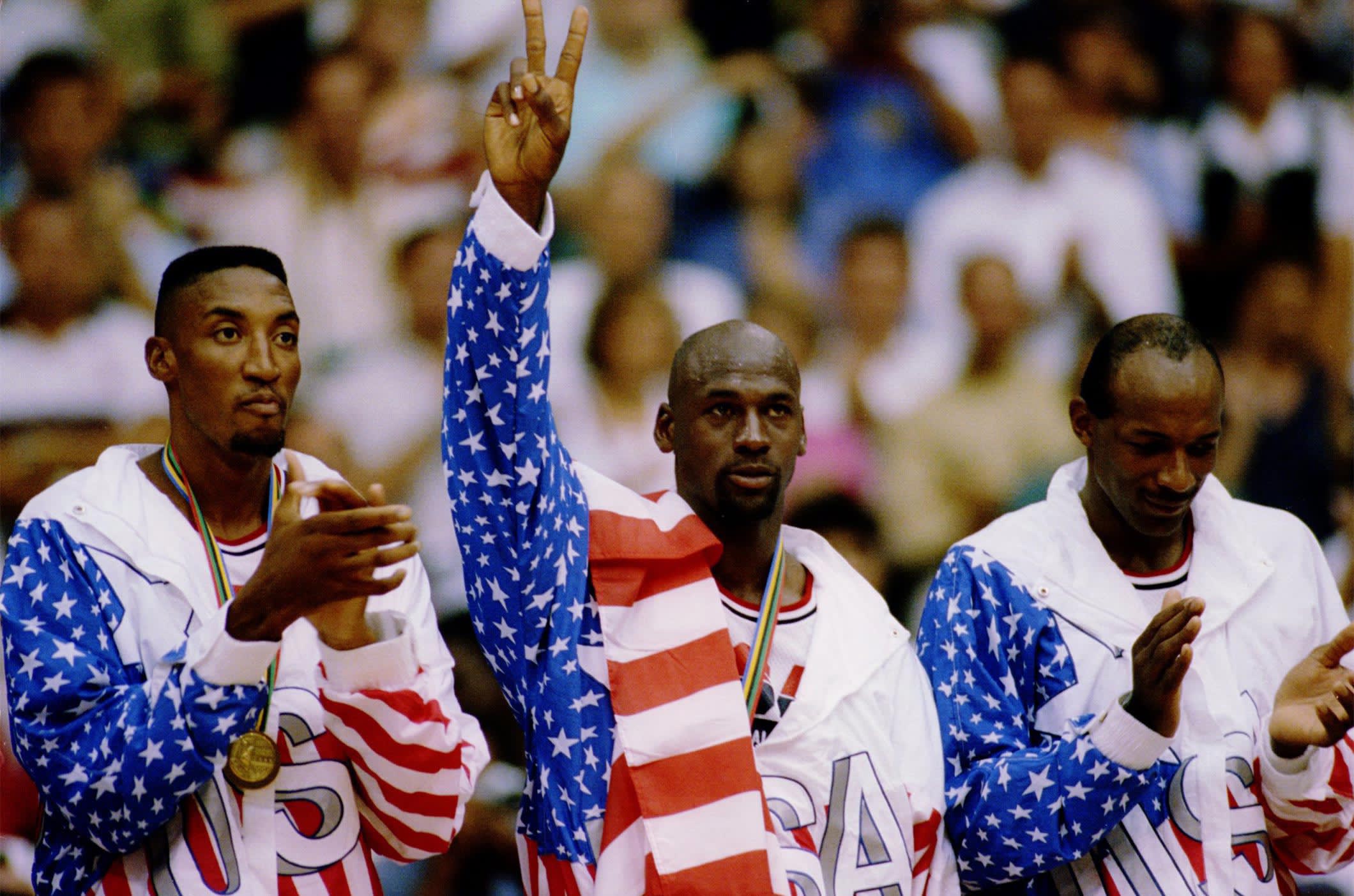

Unforgettable sporting moments included 32-year-old Linford Christie’s victory in the 100 metres, Belarusian Vitaly Scherbo’s haul of six gold medals in gymnastics, and 13-year-old Fu Mingxia’s high dive, winning gold for China with Gaudí’s Sagrada Família basilica in the background. The Games were also the first to include a US Olympic basketball team with active NBA stars: the “Dream Team”, which featured the likes of Michael Jordan, Magic Johnson and Charles Barkley.

Meanwhile, the host nation secured 22 medals, including 13 golds, asserting a sporting confidence that has grown since, not least in football, tennis and cycling.

The Games were preceded by a four-year “Cultural Olympiad” – which revitalised the artistic landscape – and sporting programmes that continue to inspire residents. The “Sport for All” programme widened the opportunities for children and young people to engage in sport, while “Activate” did the same for the over 40s. Other major programmes focused on social integration, schools, and opening up Games venues to children during the summer break.

A city transformed

All 15 purpose-built venues remain in use today, as do 94 per cent of all permanent venues used at the Games. These were developed alongside other new and refurbished facilities in line with a visionary urban development masterplan, which saw the city opened to the sea and the surrounding region transformed. Described as “novel, progressive and successful”, the “Barcelona model” has been studied ever since – it even won the city an unprecedented award from the Royal Institute of British Architects.

“For me, a citizen of Barcelona, it was very clear that there was Barcelona before the Games and Barcelona after the Games,” said Pere Miró, former Director of NOC Relations and Olympic Solidarity at the International Olympic Committee (IOC), who worked closely on the organisation of Barcelona 1992. “It was a city completely transformed, in a positive way. For me, this was a great example of what the Games can do for the transformation and evolution of a city and region, and for the benefit of urban and social development.”

One of the best-known developments was the Port Olimpic sailing venue, a former industrial area whose regeneration involved decontaminating seawater and creating beaches, leisure areas and a marina.

Located between the Somorrostro and Nova Icària beaches, Port Olimpic is today known by locals and tourists for its water sports and wide range of shops, restaurants and clubs.

Similarly, the development of the nearby Olympic Village led to the redevelopment of the rundown Poblenou neighbourhood, further opening the seafront and regenerating 40km of coastline.

Outside Barcelona, a medieval town in the Spanish Pyrenees was chosen for the Segre Olympic Park white-water centre. Canoeing is now complemented by other activities, such as rafting and mountain biking, making La Seu d’Urgell a year-round tourist destination.

There were other reinventions, such as the Estació del Nord railway station, which had been abandoned for 20 years. Redeveloped for the Games with its magnificent iron and glass Art Nouveau façade intact, the station hosted table tennis and has since evolved into a state-of-the-art municipal sports facility.

Return on investment

The construction of architecturally striking venues and the city-wide renovation were complemented by transport improvements – airport expansion, a new system of ring roads and rail investment, including a new high-speed rail network. In all, around 95 per cent of the city’s budget was invested in transport links and infrastructure.

The organisers’ EUR 900 million investment generated a direct EUR 7 billion boost to the region and wider economic benefits exceeding EUR 18.6 billion, according to an independent estimate.

Since the Games, Barcelona has gone on to gain international recognition for its enlightened approach to urban management, as well as Olympic legacy planning.

“The Games also created an intangible legacy: a sense that the whole of society was working together for a common goal, in a common effort towards something positive for the city and the country,” added Miró. “It was something that brought people together. We were very proud of this. This intangible legacy of the Games was very important.”