Staring at her reflection in the old recording booth window, Michelle Graham recalled a seemingly long-lost era.

“It is very, very sad,” Graham, 48, said, pausing to look around the damp, moldy studio. “I just wish you all had seen it back the way it was before.”

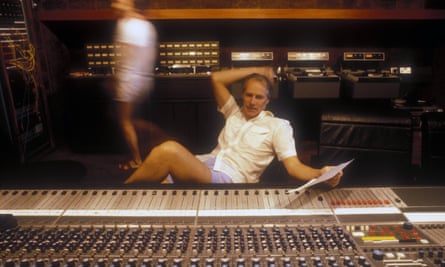

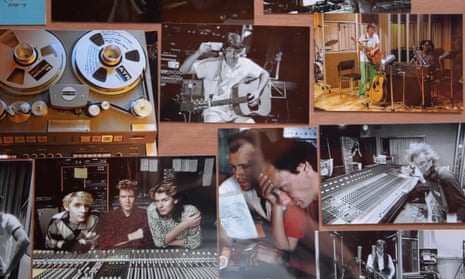

When it was opened by George Martin in 1979, AIR (Associated Independent Recording) studio was a state-of-the-art recording facility which just happened to be in Montserrat, a tiny British Overseas Territory in the eastern Caribbean. Stars including Paul McCartney, Elton John, Boy George, Stevie Wonder and Sting passed through this studio to record some of the biggest hits of a generation.

Seventy-six albums were made here before the studio shut its doors in 1989, when the island was devastated by a hurricane. Six years later, Montserrat took another hit when the Soufrière Hills volcano began erupting, ultimately destroying the island’s capital, Plymouth, in 1997.

Nowadays the wasp-infested building which once housed AIR is a mere shell of its former self. But for many Montserratians, it remains a symbol for what their nation used to be.

Graham was only 15 when she first sang backup here – for James Taylor – but she went on to record with many more stars. “When they came around, they obviously asked for island singers,” Graham recalled. “I don’t even remember all the people I sang backup for.”

Jimmy Buffett’s Volcano was recorded in Montserrat, inspired by the island’s then quiet mountain. Elton John recorded three albums. Paul McCartney recorded Tug of War, including the hit single Ebony and Ivory with Stevie Wonder. Other artists who recorded here included the Rolling Stones, the Police, Rush, Black Sabbath, and Duran Duran.

“I didn’t realize how important these people were until I was older,” said 35-year-old Montserratian Veta Wade, whose parents sent her to the United Kingdom when the volcano began erupting. “I mean, I went to primary school with Eric Clapton’s daughter.”

“You saw them all the time,” said David Lea, who moved to Montserrat from Florida in 1980, and still lives there. “I remember seeing Sting learn to windsurf, and nobody gave a hoot.”

The biggest names in 1980s music are just footnotes in Montserrat’s collective memory. Remembering a local restaurant, Graham recalled it first as the place “that had the best chicken on this side of the island.” Only then did she mention it was also the place where Sting and Dire Strait’s Mark Knopfler first came up with Money for Nothing.

Following the island’s devastating volcano eruptions, some of the musicians who had come to love Montserrat – Paul McCartney, Arrow (the Montserratian behind the hit Hot, Hot, Hot), Phil Collins, and others – held a benefit concert for their beloved island.

Talk of turning AIR studio into a museum never materialized, and the studio and posh house with views of the Caribbean is slowly decaying. The pool is filling with algae-stained water, vines are taking over the walls, and its roof and floors are caving in.

While it draws the occasional music enthusiast who wants to stand in the place behind some of the 80s’ biggest hits, AIR studio is slowly slipping away. It is dying the same way it lived: tucked away, out of the public’s eye.

“I think it was deliberate,” Graham said. “They wanted a place of total, absolute privacy. It was not made public.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion