THE HISTORY OF ARIEL

ONE OF the most classical stories in all of motorcycledom is the legend of Ariel. Even though it has not been produced since 1965, the marque is still well known throughout the world for its magnificent Square Four—a model that connoisseurs of fine motorcycles consider to be a classic of incomparable stature. The company also has an enviable record in the competition sphere; the illustrious Ariel Singles scored many trials wins in the preand post-World War II days.

The story of this colorful British marque began in 1898 when a 2.25-hp tricycle was produced. The head of the infant company was a Scot named Charles Sangster, who had been producing bicycles for quite some time.

GEOFFREY WOOD

This single-cylinder trike soon gave way to a 2.5-hp motorcycle in 1903, which had such primitive features as an automatic intake valve (it was sucked open by the downstroke of the piston), a chassis with no suspension and a singlespeed belt drive.

During these early years Sangster worked hard to make his motorbike reliable. By 1905 he felt confident enough to enter his first race, the elimination race in the Isle of Man, which determined the British machines for the Gordon Bennett Race in France. The winner of this elimination event happened to be a 6-hp twin-cylinder Ariel, which averaged 42 mph. The Twin weighed only 110 lb., but it was trounced quite badly in the big Continental event.

In 1906 the company produced a new Single that had mechanically operated side valves, a battery ignition and a sprung front fork. The following year a magneto was used for ignition. These models continued until 1910.

In 1910 a new Single was produced that had side valves and a belt drive with a variable gear ratio. In 1912 the 3.5-hp thumper featured a chain drive and two-speed gearbox in the rear hub. In 1913 this was changed to a three-speed countershaft gearbox with a belt drive. This model proved to be an exceptionally sound design, and Ariel proceeded to win the team prize in both the English and Scottish Six Day Trials. The Single was followed in 1915 by a two-stroke, but at this time the factory was converted to wartime production.

After the war the range consisted of a 3.5-hp Single and a 6-hp Twin, with belt drive still being retained. The company also experimented with a spring frame, which had a triangulated fork that worked on coil springs mounted just below the seat. Nothing much became of the springer, and it was soon dropped as an expensive and impractical proposition.

By 1922 Ariel was firmly established as one of England’s leading names, and a comprehensive brochure listed no less than eight models. The first was a 500-cc Sports Single with measurements of 86.4 by 85mm. A three-speed gearbox with ratios of 14.3:1, 7.75:1 and 4.6:1 was used in conjunction with a belt drive, but a surprising innovation was a hand clutch lever. Cog swapping was done by hand, and the oil pump was also hand operated. This 3.5-hp thumper had a magneto ignition and girder front fork, with the tire size being 2.40-26. The duel tank held 2 1/8 gal. and the oil tank held 2.5 pt. The wheelbase was a long 56 in., and the weight was only 235 lb.

The next model had the same engine but with a foot clutch, and the gear ratios were 16.5:1, 8.75:1 and 5.3:1. This Touring model weighed 275 lb. and had 4.25 in. of ground clearance.

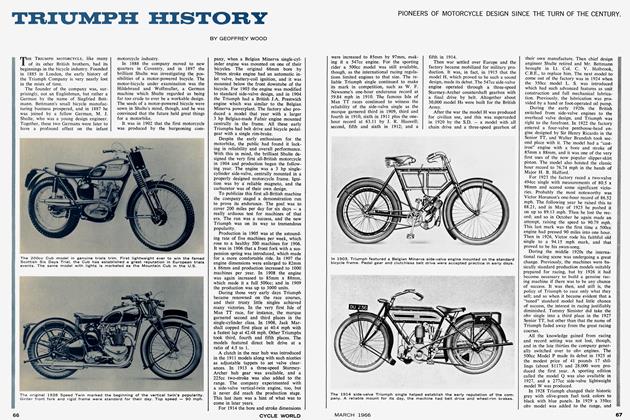

The third and fourth models listed were 6to 7-hp 796-cc V-Twins, one with a sidecar and one solo. The Twin weighed 300 lb., and had gear ratios of 14.3:1, 7.75:1 and 4.6:1. One other Twin was listed in the brochure which had a 994-cc MAG (Motosacoche of Geneva) engine with a bore and stroke of 82 by 94mm. This engine was of the inlet-over-exhaust valve design. The model weighed 334 lb. of 92 by 100mm. This 4.5-hp beast was produced in both solo and sidecar trim, and it featured a chain drive. Two other sidecar models were produced at that time. It is interesting to note that several of these 1922 Ariels had internal expanding brakes in place of the common caliper brakes on the wheel rims.

Ariel also produced a huge 665-cc Single then that had a bore and stroke

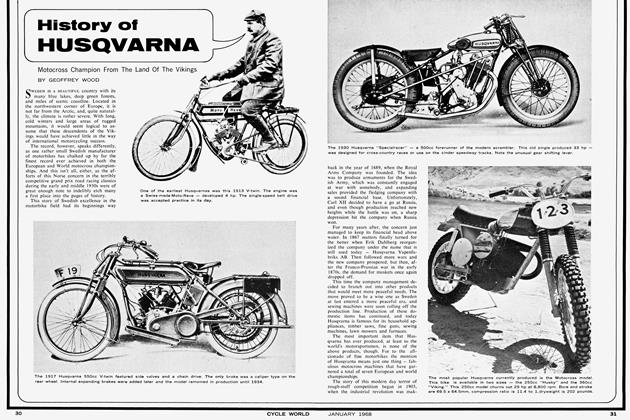

During the middle 1920s the British industry was gradually changing from side-valve engines to the overhead valve design. Ariel introduced their first overhead valve Singles in 1926, and these models proved to be so sound that they soon became one of the largest manufacturers in the world. The 500-cc ohv models had a mechanical oil pump (double plunger). In 1927 the bike became more modern looking when the “saddle” fuel tank was adopted that went over, instead of between, the top frame tubes.

By 1928 Ariel was recognized as a leader of the industry. Their range of models included both side-valve and ohv machines. The side-valvers were 557-cc Singles with a bore and stroke of 86.4 by 95mm and had an alloy piston and Lucas magneto ignition. Output was 5.5 hp, and a three-speed Sturmey-Archer gearbox had ratios of 14.0:1, 7.6:1 and 4.75:1. The frame was a strong singleloop cradle type, and braking was accomplished by a 7-in. internal expanding unit. Gear shifting was still done by hand, while the weight had risen to 280 lb. The tire size was 3.00-26 on this model, and a 2-gal. fuel tank was fitted. A deluxe version was also offered that had wider fenders and a Burman threespeed gearbox.

The 500-cc ohv Single had measurements of 81.8 by 95mm and weighed 290 lb. The pushrod model had most cycle parts in common with the sidevalve model, but it produced 5.0 hp and had gear ratios of 13.0:1, 7.6:1 and 4.75:1. A super sports version was also available with a two port head and polished ports. An optional close-ratio gearbox was produced, making the sports model a popular mount with the more sporting minded riders. Wheelbase on all of these Ariels was 55 in. The appearance was beginning to take on a more modern look.

The actual power output of these early Ariels is not known since the company rated one horsepower for each lOOcc in their brochure. The SV models would do 75 to 80 mph and ohv models about 80 to 85 mph— respectable speeds for those days. These Ariel Singles were also used in the big trials events of the day, their reliability and performance enabling them to win a goodly share of the awards. It might be mentioned that the trials of that era were more of an endurance type than the observed type, with stamina being more important than performance.

During the late 1920s England assumed undisputed worldwide leadership in motorcycle design and sales, and a great rivalry existed between the companies to produce a superior machine. Motorcycling had become very popular, with the increasing sophistication of the machines that were available, and a great demand was created for a refined machine of superior performance.

Ariel was one who had its eyes on this new market. Plans were laid to produce the most luxurious motorcycle ever offered to the public. Because it took several years to design and test the brainchild, it was not until 1931 that the model was listed in the brochure. This new Ariel was called the Square Four, and it created a sensation that has endured to this day.

The new Four had a unique design, which used two crankshafts at a right angle to the frame. These two shafts were geared together on the left side so that they counter-rotated toward each other. The advantage of this design was its superb engine balance and compactness; the smooth flow of power was a revelation to a world that knew only the throb of a Single.

The con-rods all used roller bearing big-ends, but the timing side mains were all plain bearings. Large roller bearings were used on the drive side shafts, and the alloy crankcase was naturally quite large. The cylinder and head were both of cast iron, with one exhaust port being used on each side of the head. The valves were mounted in a parallel position in the head, since a hemispherical combustion chamber would have required a complicated valve train and a large head. The valves were actuated by a single overhead camshaft, which was chain driven from the right side of the engine. A single carburetor was used, and ignition was by a magneto.

The massive engine was mounted in a wide duplex cradle frame, and a fourspeed handshifted gearbox was mounted in plates behind the engine. It might be mentioned here that Burman made an optional footshift conversion kit, since those were the days when England was changing over to the footshift gearbox. The frame was still rigid, of course, and a girder front fork was used.

This first Square Four was a superbly finished mount for the aristocratic rider, with the 500-cc engine providing a smooth but rapid performance. In 1932, Ariel decided to increase the bore and stroke to 56 by 61mm, thus providing 600cc. In 1933 the oil tank was dropped in favor of a wet sump system. This made the Ariel run much cleaner, since the oil lines were done away with, and the Ariel Four became known as the “Rolls Royce of motorcycles.”

(Continued on page 78)

Continued from page 77

The Square Four continued in production through 1936 in this trim, and soon it had a reputation all over Europe as the prestige machine par excellence. Top speed was listed as 90 mph, and acceleration was second to none. The Four never did sell in really large numbers, due to its high cost in the post-depression days of the middle 1930s. So the man who rode one was considered a man of substantial means.

Meanwhile, the company was aggressively improving its line of Singles in an attempt to compete with the many fine Singles produced at that time. In 1931 the company produced their famous 30 degree “sloper” in both side-valve and overhead valve designs. The side-valve model was 555cc, while the ohv model was available in both 250and 500-cc sizes. Ariel even produced a special four-valve model that was tuned for high-speed performance and won many grass track and scrambles races.

The next big change came in 1934 when the slopers were phased out and a new line of vertical Singles introduced. In this era of great classical motorcycles in England, Ariel was right at the forefront with a superb range of machines. The following year Ariel expanded their range even further, listing ten magnificent models in the 1935 brochure.

One of these bikes was the old 550-cc side-valve Single that was still popular as an inexpensive and reliable sidecar model. The compression ratio was a mild 5.0:1, and either a 3or 4-speed handshift gearbox was available. Then came the 250-cc overhead valve model with measurements of 61 by 85mm. This utility Single ran on a 6.0:1 compression ratio. The 72 by 85mm 350-cc Single and 81.8 by 95mm 500-cc thumper came next, and these sloggers all had hand gearshifts and 19 in. wheels.

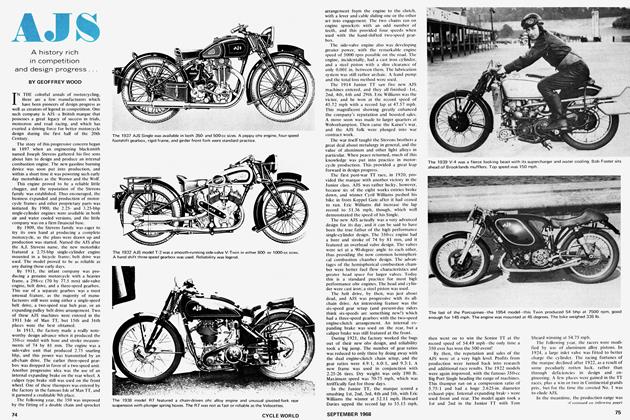

The models that appealed to the sports minded riders were the 250-, 350-, and 500-cc Red Hunters, special bench tested Singles that had many exciting specifications. The idea was to produce a fast sports Single that would streak down a country lane. A wide range of options allowed an owner to purchase a Red Hunter in trials or scrambles trim.

The 250-cc model ran on a 7.0:1 compression ratio and had 3.00-20 tires, a 2.5 gal. fuel tank and sports cams. The performance was listed as 70 mph, which was remarkable for those days. The 250, like all the Red Hunters, had a black frame and a red fuel tank with gold striping plus a footshift gearbox.

The 350-cc Red Hunter was tuned to run 80 mph on a 1.0-in. carburetor. This model also had a 2.5-gal. fuel tank and a 0.5-gal. oil tank. The big 500-cc model had a 6.5:1 compression ratio, but 7.5:1 was available for use with 50/50 petrol/ benzol fuel. The carb size was 1 1/8 in., and the fuel tank size was 3.25 gal. The oil tank held 0.75 gal. The 500 was available with either a oneor two-port exhaust system, and top speed was listed as 1 OOmph. The rear tire was a 3.25-19 block tread, front was a 3.00-20 rib tire.

All of the Red Hunters had racing cams, ground and polished ports, a polished con-rod, and a bench tested engine. The brakes were up to the performance, too, since the 7-in. binders had wide, 1.25-in. shoes, and ribs were cast on the brake drums to help dissipate heat. A sports type of quickly detachable headlight was fitted, and a buyer could order his Single in competition trim with an upswept exhaust, crankcase shield, small fuel tank, magneto, knobby tires, sports fenders, and special bars.

These Red Hunters performed magnificently in trials events, as was attested by the 193 5 brochure which proudly listed wins in the Scott, Colmore, Kickham, Victory, Bemrose, Cotswold, Mitchell, Wye Valley, and Gloucester Grand National events. Ariels also won the 250and 500-cc classes of the famous Scottish Six Days Trial, and Gold medals were won on both the “A” and “B” teams in the ISDT.

The most prestigious model in the range was, naturally enough, the luxurious Square Four. The Four had 3.25-19 tires and 3.25-gal. fuel tank. It had a classically elegant appearance with gold striping on a black finish.

The next improvements came in 1936 when the side-valve Single was increased to 600cc (86 by 104mm), and all the models had a foot gearshift. The marque also offered the 500-cc Red Hunter in genuine competition trim. These models were soon tuned by men such as S.W.E. Hartley to clock 109 mph on alcohol fuel. Perhaps the most remarkable record was set in Australia, when Art Senior clocked a fantastic 127 mph on his Single. The Australian record was set in 1938, and it stood for many years until after the War, when a 1000-cc Vincent finally exceeded this speed. The works trials and scrambles team included such greats as Jack White, Len Heath and Jimmy Edward all of whom continued the Selly Oak tradition by winning many events.

The next change came in 1937 when the overhead cam Four was dropped in favor of a new pushrod engine. The new Four had a lower end similar to its predecessor, except that plain rod bearings were used in an effort to lower production costs and make the engine quieter. A centrally located camshaft operated the pushrods and made the external appearance much cleaner.

Perhaps the most notable item about the new Four was that a massive 1000-cc version joined the earlier 600-cc size in the stable. The brutish 1000 had measurements of 65 by 75mm, and it produced 38 hp at 5500 rpm. This much pressure made the Four a genuine 100-mph model, and its acceleration was by far the fastest of any production roadster available then. The new Four also had a Burman four-speed footshift gearbox, a single-loop cradle frame and a dry sump lubrication system.

In 1939 the marque made another great step forward when they produced an optional spring frame on all but the 250-cc models. The design was rather unique in that it had swivel links connected to the plunger boxes containing coil springs. The idea was to provide axle movement in an arc, which helped maintain constant chain tension. The suspension gave about three inches of travel, making the Ariel an exceptionally comfortable bike for those days. A modification was also made to the girder fork when a pair of small auxiliary dampening springs were added to control the rebound.

(Continued on page 80)

Continued from page 79

The range for 1939 was much the same as before, except that a Deluxe Four was produced for the connoisseur which had deeply valanced fenders, a pair of fishtail mufflers, lots of chrome and an impeccable finish. There were also many small technical improvements to the Singles.

The final few years of pre-war sport had Ariels winning a goodly share of the awards. In 1938 G.F. Povey won the Scottish classic on his 350-cc model, and Ariels won four gold medals in the 1938 ISDT. Other pre-war Ariel achievements include a 96-mph clocking by L.W.E. Hartley with a 557-cc SV model and Ben Bickell’s 111.42-mph lap at Brooklands with his 500-cc Four that had a Powerplus supercharger fitted.

During the war Ariel met military needs, but in Sept, of 1945 the company was able to resume production of roadsters again. In 1947 Mr. Sangster sold out to Birmingham Small Arms, but Ariels continued as before with 350and 500-cc Singles, the 1000-cc Four, and 600-cc SV models being produced. For 1948 Ariel improved their range by adopting the telescopic front fork with hydraulic dampening.

The marque participated in most of the early post-war sporting events. In trials and scrambles events Ariels were always well placed; the Singles even got involved in road racing when the Isle of Man held their now defunct Clubman races for standard machines. In the 1947 Senior Clubman TT G.F. Parsons captured 3rd, and other riders placed well until 1950 when the other companies’ pseudo-racers made their debut. Perhaps the most surprising Ariel showing was in the 1947 Dutch Grand Prix, where a fellow by the name of J. Schot piloted his Red Hunter into 6th place— the first and only time that the marque had gained a world championship point!

The following year Ariel created a sensation with their 1949 brochure, which listed a wide range of models that included the Singles, a new 500-cc Twin, and a redesigned Four. The 63 by 80mm Twin was available with either a rigid or spring frame, and it was produced in two versions: a 25-hp (at 5500 rpm) model that ran on a 6.8:1 compression ratio and a 27-hp (at 6000 rpm) model that used a 7.5:1 ratio. These Twins had a very cleanly designed engine, but they never experienced the popularity of the Red Hunters or the Four.

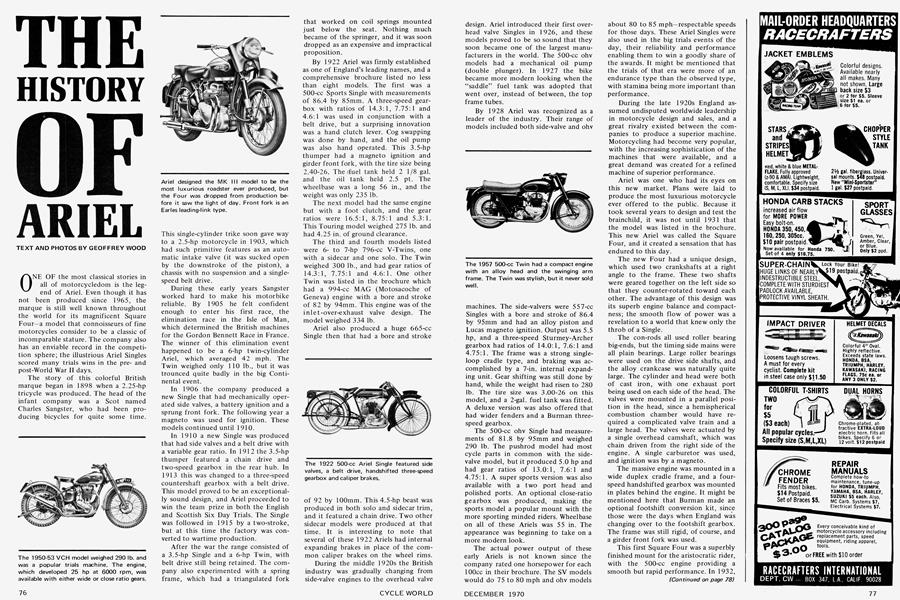

The new Square Four, called the MK I, was a vastly improved motorcycle with its all-alloy engine that reduced the weight from 420 lb. to 385 lb. (the springer weighed 25 lb. more). The alloy engine ran much cooler, and the appearance was sheer artistry in metal. Operating on a 6.0:1 or 6.8:1 compression ratio, the Four developed 34.5 hp at 5400 rpm and ran 95 to 100 mph. The acceleration was fantastic, with standing quarter-mile times of around 13.5 sec. being reported. The MK I model was the most luxurious roadster produced anywhere in the world; even today these beautiful Fours are highly prized by collectors.

In 1950 the company turned its thoughts to producing a genuine competition model named the VCH or Comp Red Hunter. The idea was to produce a 500-cc Single that was suitable for both trials and scrambles, and the emphasis was on light weight and fine handling. The 81.8 by 95mm alloy engine ran on a 6.8:1 compression ratio and churned out 25 hp at 6000 rpm, with great torque being produced at low engine speeds. Two gearboxes were available, a close ratio box for motocross racing and a wide ratio box for trials events. The ratios on the two boxes were 15.3:1, 9.7:1, 7.2:1 and 5.75:1 for the close ratio box, and 19.1:1, 12.6:1, 9.16:1 and 6.05:1 for the wide ratio box.

The VCH model was quite light at 290 lb. Its stamina soon made it popular with trials riders, many of whom won several of the top events then. Bob Ray of the works team was one of the most successful riders. Ariels were always a force to be reckoned with in trials events. Harold Lines proved to be the marque’s best motocrosser, but he seemed to lack a wee bit in the horsepower department compared to the BSA Gold Stars, Matchless Singles, and FN thumpers.

The next big year for Ariel was 1954 when they introduced a new swinging arm frame on all but the Four, which retained the old plunger suspension. The new frame kept the Ariels totally modern, as everyone was making the change at that time, and the riding comfort reached a new high. The company also produced a new 650-cc Twin called the Huntmaster that produced 40 hp at 6200 rpm, and a 200-cc Colt was added to the range as an inexpensive utility model.

The 500-cc Singles were also improved by using alloy for the cylinders and heads, while the Red Hunters had the pushrod tunnel cast into the cylinder in an effort to provide a cleaner running engine.

The model that really made the news then was the fabulous MK II Square Four, a bike that was truly the Rolls Royce of motorcycles. The MK II had a completely new engine with a massive alloy cylinder and head plus an improved lower end. The head featured a set of bolt-on exhaust manifolds that had two ports each, so the MK II soon became known as the Four Port model. This engine produced 42 stampeding horses at 5800 rpm, and the top speed was increased from 105 to 110 mph. The acceleration was shattering, and several road tests obtained standing quarters of 12.9 to 13.2 sec.

The appearance of the MK II was impressive. A huge 6-gal. fuel tank was used that had a concave chrome panel near the top on each side. A buyer could have his choice of either a solo or dual type seat. The weight of the MK II was 450 lb., the wheelbase was 56 in., and the tire sizes were 4.00-18 rear and 3.25-19 front. A new Burman gearbox was also used with ratios of 11.07:1, 7.1:1, 5.46:1 and 4.18:1, which gave the MK II a high cruising speed combined with shattering acceleration.

Meanwhile, Ariel had not forgotten about the competition scene and designed a pair of new models for trials and motocross racing. These two sports had developed to the point where one design was not suitable for both events, so a more specialized mount was designed for each.

The trials model was named the HT. This bike was destined to achieve fame and glory a few years later when Sammy Miller became a works rider. The HT featured an alloy engine of low (but unknown) power output that ran on a 5.6:1 compression ratio. The bore and stroke was the classic 81.8 by 95mm, and slow cams and heavy flywheels were used to obtain low speed pulling power.

The frame, a light swinging arm type, was very special, since 1954 was the year when most factories dropped the old rigid frame in favor of a springer. The wheelbase was only 53 in., and the fork angle was very steep for precise steering at slow speeds. The dry weight was only 290 lb., due to the use of alloy for the fenders and the 2.0 gal. fuel tank. The wide ratio gearbox had ratios of 19.3:1, 14.7:1, 9.46:1 and 6.02:1. Ground clearance was 7 in.

(Continued on page 82)

Continued from page 81

The HS model had a bench tested engine that developed 34 hp at 6000 rpm, and this was slotted into a rugged frame with a close ratio gearbox that had ratios of 16.1:1, 10.2:1, 7.9:1 and 6.02:1. The compression ratio was 9.0:1, and the dry weight was 318 lb. The tire sizes were 4.00-19 rear and 3.00-21 front; the same as the HT model. This scrambler was a good bike, though it never achieved the success that its less powerful brother did in trials events.

During the next few years the Ariels underwent only minor changes, but in 1957 the Square Four was given a face-lifting with a larger oil tank, a headlight nacelle, and a large full-width front hub that was cast in alloy. These changes made the luxurious Four even more appealing, and it continued to be the most prestigious (and expensive) motorcycle in the world.

However, change was in the air. Sales were falling off in Europe due to the rise in the standard of living that allowed the populace to afford automobiles. Ariel responded by producing the 250-cc Leader, a two-stroke Twin with sheet metal paneling that provided excellent weather protection. The Leader was followed by the Arrow and Arrow Sports, which were unstreamlined standard models. A tiny 50-cc ohv Pixie came next, an attempt to build a “schoolboy” model at a very low price.

These new Ariels proved to be so popular with the everyday rider that a decision was made early in 1959 to halt production of all the big four-strokes in order to meet the demand for the new two-strokes. This was a tragedy. The company had already designed and tested the MK III Square Four, the most luxurious motorcycle the world had ever seen. The MK III had an Earles leading-link front fork similar to those on the BMW, and it was claimed to provide the most comfortable and stable ride ever produced on a motorcycle.

As it transpired, the MK III never saw the light of day. This model would have been the most regal of a long line of magnificent Fours. Even today there are few machines which could approach its luxurious specifications.

Meanwhile, during the middle 1960s, the Japanese manufacturers were making serious inroads into the world market with their lower priced lightweights.

Ariel sales began to fall, and soon the company was failing to show a profit. If Ariel had had a line of big bikes to fall back on, they might have survived. But the desire of the Burman company to sever their contract (due to the smaller numbers that were involved) was the final blow that felled the marque. In the autumn of 1965 the last Ariels left the factory.

There was one final chapter to the Ariel story, and this one proved to be the greatest. For this story we must go back to 1956 when Sammy Miller of Ireland was hired onto the works trials team. Sam spent the first few years in learning how to set up his big Single and master the toughest courses. By 1958 he showed enough class to finish 2nd to Gordon Jackson (AJS 350) in the famed Scottish Six Days Trial.

During the next few years Miller dedicated himself to modifying his Ariel. First came a smaller front brake and an upswept exhaust. Then came some mods to the steering geometry. An alloy oil tank and slimmer fuel tank came next, followed by a new Reynolds 53 1 tubing frame, designed to contain the oil tank. Miller also used a Norton front fork and fiberglass for the fenders, primary cover, magneto shield, seat pan, chain guard and number plates. The dry weight finally ended up at an unbelievable 242 lb. Wheelbase measured 52.5 in., and the ground clearance was 9.0 in.

This thumper proved to be a magnificent trials machine, enabling Sammy to win the coveted British Championship in 1959 by defeating his arch-rival, Gordon Jackson. Sammy then proceeded to dominate the British Championship, taking the title the next five years in succession (1960-’64). The “maestro” also won the coveted premiere award in the Scottish classic in both 1962 and 1964. Then financial problems caused the factory to terminate its contract with Miller. This proved to be a significant turning point in trials history; Miller went to Bultaco and thus started the trend to 250-cc class trials machines. It can truly be said that when Ariel passed from the trials scene, the lusty big Single passed too.

The Ariel, however, refuses to pass from the scene. The Ariel Motorcycle Owners Club and thousands of afficionados are keeping the name alive through their dedicated restoration of all the great classics. To some, the majestic Square Four is the most regal. Others appreciate the pre-war Red Hunter classics, which are the prototypes of the era of great Singles. Then there are those who love the HT trials model, the last big Single to win the Scottish. All of these magnificent models well represent that proud era when Britannia reigned supreme; perhaps the greatest era that motorcycling has ever known.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

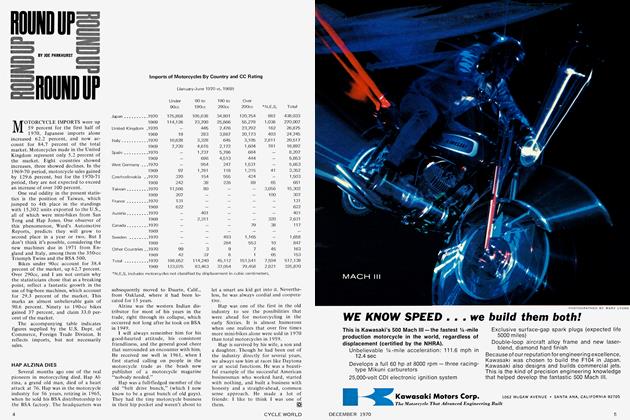

DepartmentsRound Up

December 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1970 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

December 1970 By Jody Nicholas -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

December 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Features

FeaturesEuropean Touring

December 1970 By Stephen J. Herzog -

Features

FeaturesAnd Now...The Case For Traveling Light

December 1970 By Dan Hunt