The Life and Death of Anthony Lewis, a 'Tribune of the Law'

The author of Gideon's Trumpet changed the way legal issues are covered and understood in America.

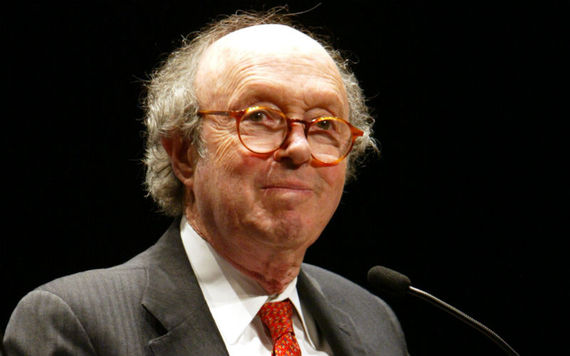

The great legal writer and journalist Anthony Lewis has died -- at age 85, at his home in Massachusetts, on the eve of oral arguments in two epic gay rights cases he surely would have been able to explain better than most. One of his successors at the New York Times, Adam Liptak, has written a fine obituary that gives you a flavor for how talented Lewis was and how significant was his impact on contemporary coverage of legal events and issues.

The headline of the obit says that Lewis "transformed" coverage of the United States Supreme Court, and he did. But he did much more than that. He transformed coverage of the broader beat of the law, and he inspired generations of writers (and lawyers and judges, for that matter) to try to better explain and translate legal jargon into phrases and concepts that laypeople could more easily understand.

Lewis' masterwork, Gideon's Trumpet, was a piece of art for precisely this reason -- word by word, simple sentence by simple sentence, he deconstructed the Sixth Amendment's right to a fair trial, and murky Supreme Court procedure, and state law, and the insular world of Washington law firms, and all the other satellite topics that revolved around that seminal case. Here is a representative passage:

The case of Gideon v. Wainwright is in part a testament to a single human being. Against all the odds of inertia and ignorance and fear of state power, Clarence Earl Gideon insisted that he had a right to a lawyer and kept on insisting all the way to the Supreme Court of the United States

His triumph there shows that the poorest and least powerful of men-- a convict with note even a friend to visit him in prison -- can take his cause to the highest court in the land and bring about a fundamental change in the law.

But of course Gideon was not really alone; there were working for him forces in law and society larger than he could understand. His case was part of a current of history, and it will be read in that light by thousands of persons who will known no more about Clarence Earl Gideon than that he stood up in a Florida court and said: "The United States Supreme Court says I am entitled to be represented by counsel."

For his work, in 1963, he won a Pulitzer Prize (his second, his first coming years earlier with his equally trenchant work covering the civil rights movement). Afterward, taking the longer view, Lewis wrote pointedly and poignantly for decades on the op-ed page of the Times, wrote excellent books like Make No Law (about the key first amendment case New York Times v. Sullivan), and contributed regularly to the New York Review of Books.

When given the chance over the years, I always tell young journalists and young lawyers to read everything Lewis has written, because his writing was always so clear, and so accessible, and such a good starting point for more involved research on any given legal topic. Others evidently agreed. "He's as clear a writer as I think I know," former Times editor Joseph Lelyveld told Liptak. There will likely be no dissent from that opinion.

In the coming days and weeks, many people who knew Lewis better than I did will surely share their stories about his profound career covering the law and politics. We'll hear about his clever speeches, his column writing, his unique relationship with the justices of the Supreme Court, and about his relationship with his beloved wife, Margaret Marshall, the former Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Court.

I have only two such stories to share. The first is from just a few weeks ago. While preparing to write a long piece for The Atlantic on the 50th anniversary of the Gideon ruling, I naturally reached out to Tony for a few meaty quotes. Who better than he to provide context and perspective? When he responded that he was too ill to help, when he apologized to me for not being well enough to help, I felt like crying for what we all were about to lose. A kind man. A thoughtful and generous professional.

And so I prayed that he would live long enough at least to get through the anniversary, and to see how the coverage of it (not just mine) honored his key role in educating the American people about the vital right to counsel. I am thankful that he made it past March 18. And I know he both read and enjoyed the coverage of the case, even as he decried the Supreme Court's lack of commitment to enforcing the mandate of Gideon.

He lived long enough for that, but, sadly, not long enough to see the Supreme Court hear and decide the pending same-sex marriage cases. His wife, of course, played a pivotal role in Massachusetts' acceptance of same-sex marriage. In 2003, in Goodridge v. Department of Public Health, Chief Justice Marshall wrote the majority opinion in a 4-3 case that declared that the state could not deprive same-sex couples of the right to marry. Do you remember the outcry at the time? In the annals of the fight for equal rights, ten years seems like an eternity.

The Supreme Court in the next two days will indeed hear the challenge to California's Proposition 8 and to the federal Defense of Marriage Act. And excellent reporters and legal analysts will cover the story and flesh out the details between now and the end of June. But the chorus will be neither as full nor as rich without Lewis' voice, without the deep judgments he was able to render in such simple tones. What a pity that is.

My other story came almost exactly 25 years ago, on March 29, 1988. I was a journalism student at Boston University, and very much a follower of James C. Thomson, Jr., a former Johnson Administration official and Harvard man who was for both political and journalistic reasons very much connected with Tony Lewis. One day, Lewis came across the river to speak at BU. And Thomson, my mentor, arranged for me to be front and center.

By this time, I had been editor of the student newspaper, and had read and loved Gideon's Trumpet, and was planning to go to law school, and was hoping even then that I would become a reporter who covered legal events and issues. When Thomson told Lewis of my grand career designs, Lewis just looked up and smiled and said, "Why, of course you can do it." And then he signed my dog-eared copy of his book:

For Andrew Cohen, with all good wishes for his future as a tribune of the law.

As I looked upon the inscription then, it gave me encouragement, confidence -- and something to strive for. As I look back upon it now, I realize it was a typical Anthony Lewis sentence. It was clear. It was eloquent. And it evoked the kindness of a good man who revered the law and who had the talent and the wisdom to explain to the rest of us how we might fit within its orbit. I didn't know what a "tribune" was until Lewis wrote that to me. I do now.