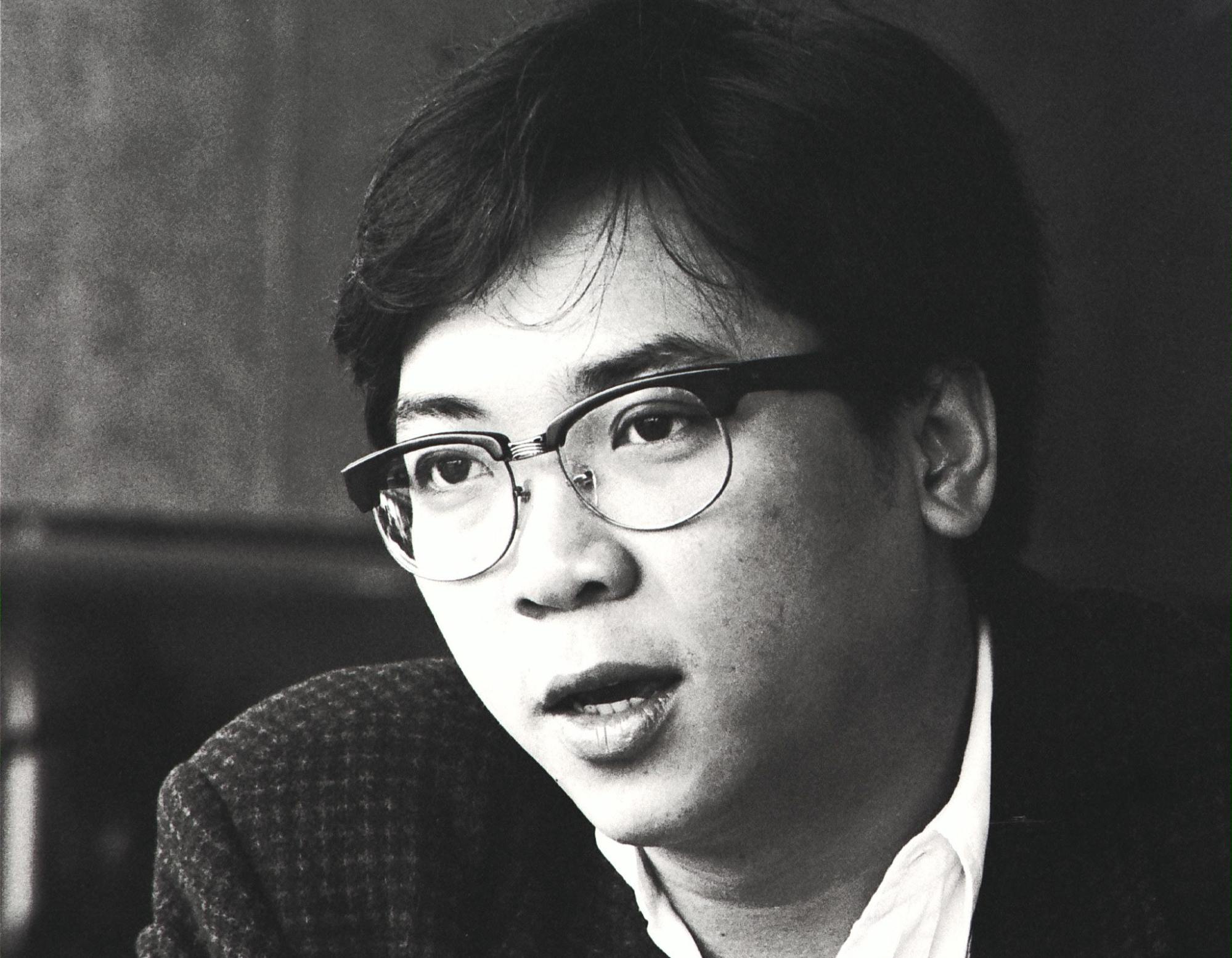

Romance meets ghost story in Hong Kong movie masterpiece Rouge, starring Anita Mui and Leslie Cheung and directed by Stanley Kwan

- Anita Mui plays a prostitute in 1930s Hong Kong and Leslie Cheung her lover and heir to a family fortune. Unable to be together, they agree a suicide pact

- Fifty years later, Mui’s ghost is looking for her lover in a changed city. Director Stanley Kwan plays on nostalgia for the past at a time of uncertainty

Part ghost story, part romance and part elegy for a vanished era, Stanley Kwan Kam-pang’s 1988 film Rouge is one of the masterpieces of Hong Kong cinema.

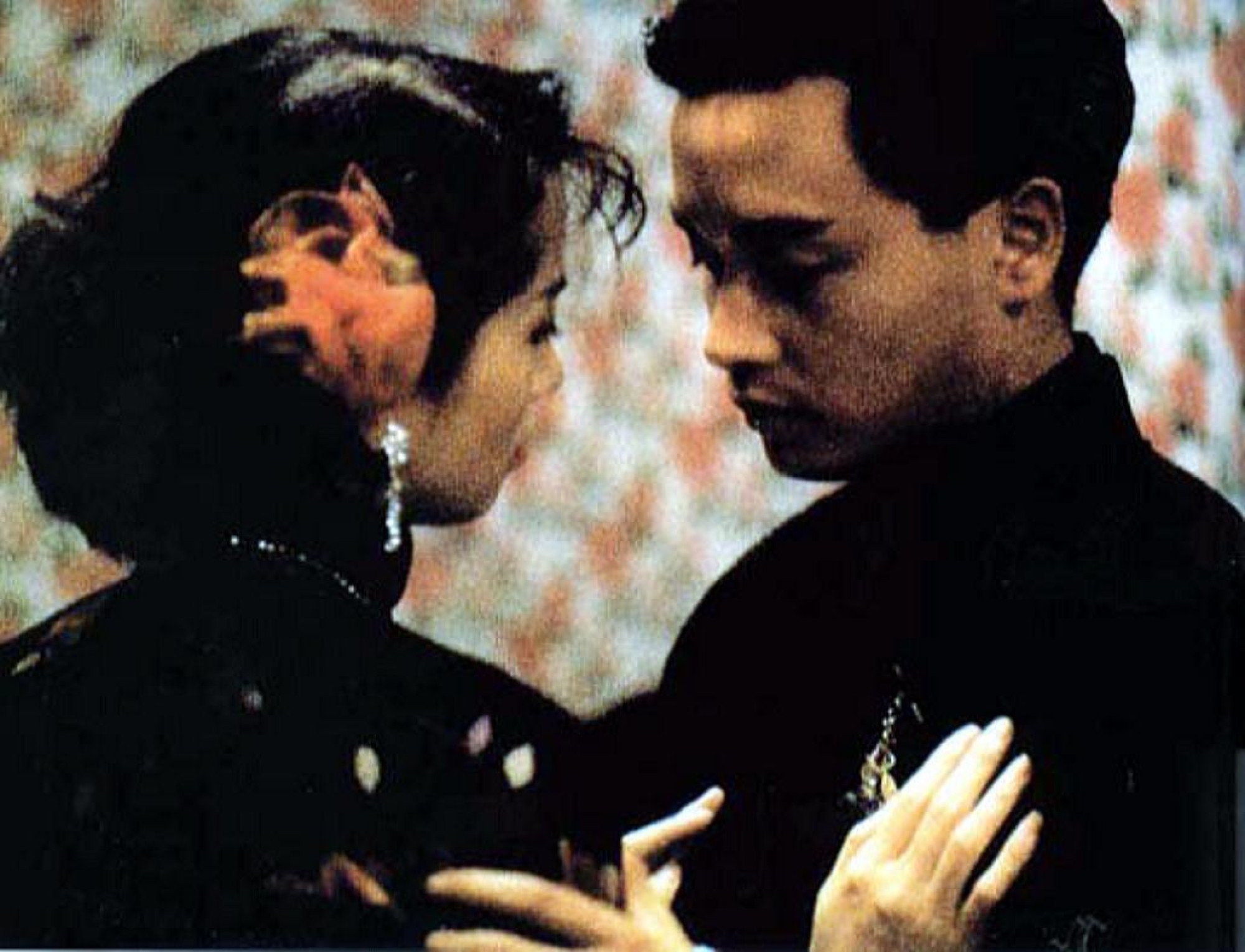

The delicately wrought story, adapted from a novel by Lilian Lee, features Anita Mui Yim-fong as a ghost from the 1930s searching for her lover, played by Leslie Cheung Kwok-wing, in 1980s Hong Kong.

Mui’s character, a courtesan, engages a somewhat reluctant modern couple in her search, allowing Kwan to contrast the outlooks of the two different generations, and to gently note the physical and cultural changes that have occurred in the city during the ghost’s 50-year search.

“Rouge provides a much-needed breath of fresh air to a Hong Kong cinema scene suffocated by the fire and smoke of mob movies,” wrote critic Perry Lam in a Post review on the film’s release in 1988. “It is an extremely well-made film, graceful, intelligent and handsome.”

Rouge was a big winner at the Hong Kong Film Awards in 1989, coming top in six categories, including best picture, best director and best actress (for Mui).

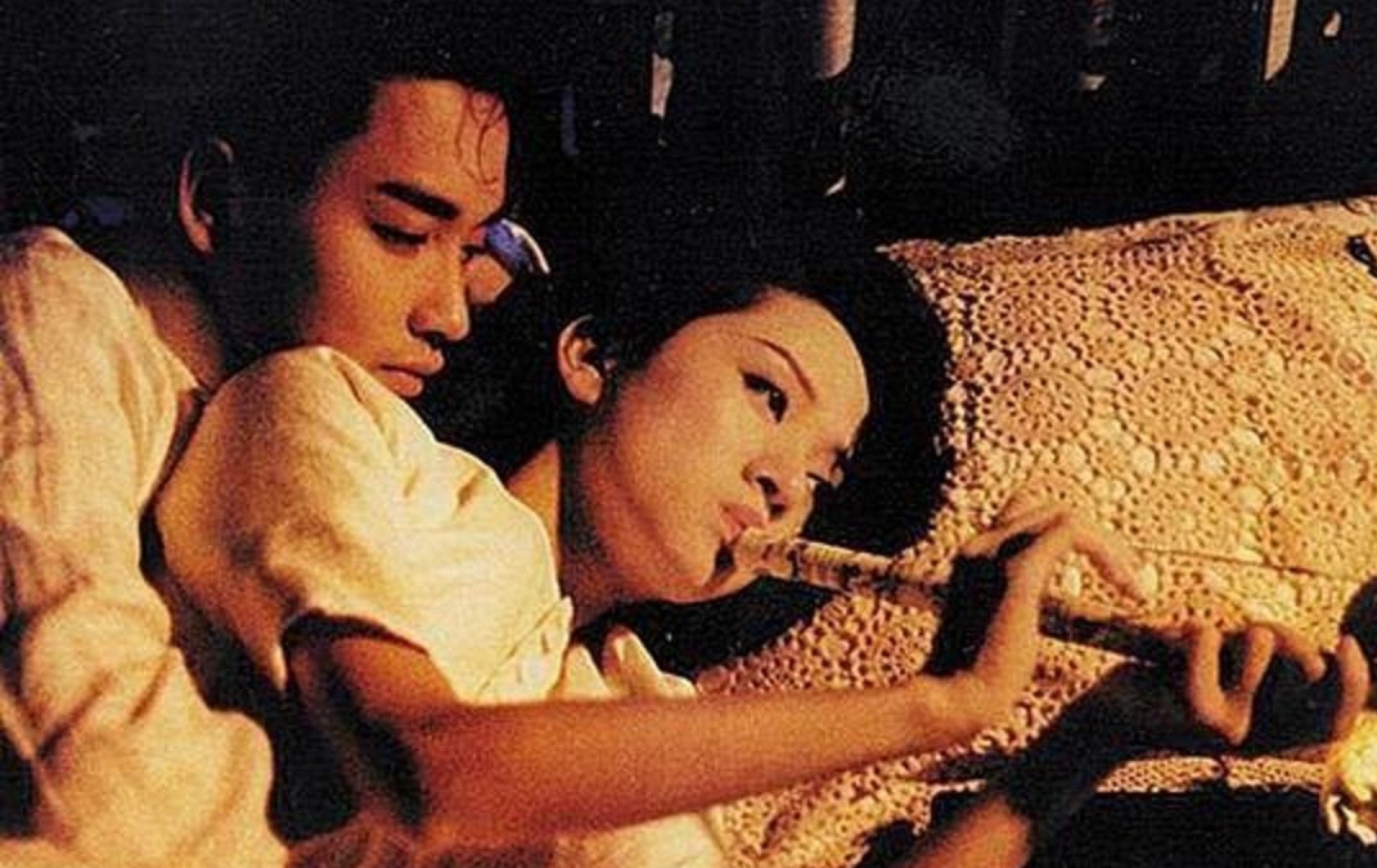

The story begins in the 1930s, when Fleur (Mui), a prostitute at an upmarket brothel, and Master 12 (Cheung), the timid scion of a wealthy trading family, fall in love. The two spend time making love and smoking opium together, but their marriage is forbidden by Master 12’s mother, who humiliates Fleur.

‘A statement against violence’: Gordon Chan on his gangster film Beast Cops

Unable to stay together, Fleur and Master 12 decide to kill themselves by ingesting raw opium, so they can meet each other in the next life, in hell. The double suicide takes place – but Fleur can’t find her lover in the next world.

Fifty years later, the ghost of Fleur is roaming modern Hong Kong, sure that she and Master 12 will find each other on the 50th anniversary of their deaths.

She meets newspaperman Yuan (Alex Man Chi-leung), and his entertainment-journalist girlfriend Chu (Emily Chu Bao-yee), when she tries to place an advertisement in a newspaper so that Master 12, in his reincarnated or ghostly form, will know where to find her.

The two agree to help Fleur in her quest, but it transpires that the events of the past did not go quite as Fleur believed.

Rouge is a ghost story, but the ghost is troubled rather than frightening. Mui, who studied how prostitutes in the 1930s carried themselves for the role, expresses her otherworldliness by simply moving slowly and quietly – “I am soft-footed,” the ghost tells Yuan.

An unassuming ghost fits neatly into the tradition of Hong Kong’s ghost films, says film critic Clarence Tsui, who is also the director of the Broadway Cinematheque in Yau Ma Tei.

“Hong Kong paranormal cinema has long had its share of benign ghosts, one example being Raymond Wong Pak-ming’s ‘happy ghost’ in the comedy franchise of the same name,” he says.

“This notion of a good ghost might stem from traditional Chinese culture and literature, in which ghosts are not necessarily the monstrous ‘other’, as they are usually depicted in Christian-inflected narratives.

“Ghosts can be the subject through which we see the foibles of those of the present day. Here, Fleur is the embodiment of certain virtues – mainly fidelity – which seem to have been lost to time.”

Kwan is a director firmly rooted in Hong Kong, and Rouge is infused with a kind-hearted nostalgia for the city. Fleur laments the fact that the Tai Ping Theatre, where she used to watch opera from the seats reserved for concubines, has become a shopping mall – it was demolished in 1981 – and is upset that Shek Tong Tsui, where she used to live, has changed beyond recognition.

Transience bothers Fleur; she finds it difficult to comprehend that things that were once important to her have been forgotten. Modern couple Yuan and Chu, meanwhile, are impressed by her passion, an emotion that they feel has disappeared from life – “We are just ordinary people,” Yuan says, when Chu compares their relaxed relationship to Fleur’s torrid romance.

Kwan, in a directing masterclass, noted that the 1980s were “dull and lifeless” compared to the “plentiful” and “delightful” 1930s.

“There’s a scene in Rouge when Fleur tells stories from the 1930s – something which jolts Yuan into realising it’s a ghost he’s talking to,” Tsui explains. “His response is, ‘I’m not that good in history!’

“The scene is there to highlight Yuan’s fear, but it’s also Kwan’s – or writer Lilian Lee’s – critique of the younger generation’s ignorance of history during the gaudy, greed-is-good decade that was the 1980s. Yuan’s search for Fleur’s paramour awakens him to a past he’s not aware of.”

Rouge provided me with the chance to explore a nostalgia for [old] Hong Kong that people were feeling

Rouge has Kwan’s directorial stamp, but he wasn’t the first choice for director. Terry Tong Gei-ming was originally assigned to the film, but dropped out as he felt the production was taking too long to start. The producers intended Kwan to make a standard ghost story, but scriptwriter Chiu Kang-chien had other ideas.

“After he read the novel, he said that it was actually a love story, and shouldn’t be made as a ghost story,” Kwan told Sasha Chuk in an interview for the Criterion Collection DVD release.

“In the film, we never see Fleur flying around as a ghost. I told him he’d written her as a normal human being.”

Anita Mui’s 10 best films ranked, as biopic of her life nears release

Chiu also added scenes of 1930s Hong Kong which are not present in Lee’s book. But direct references to the looming 1997 handover, which exist in Lee’s novel, were put aside.

Although the political changes were not directly addressed, they did influence Rouge, Kwan said in a masterclass presentation.

“It was after [the Sino-British Joint Declaration in] 1984, and people were confused. They did not know whether to stay in Hong Kong or leave. Rouge provided me with the chance to explore a nostalgia for [old] Hong Kong that people were feeling.”

Screenwriter Chiu also pushed for Anita Mui to play Fleur, Kwan said. Mui was considered by many to be the wrong choice before filming, as she had mainly appeared in romantic comedies, and was not thought to possess the “classic” Chinese beauty necessary for Fleur.

“Anita Mui upended Hong Kong show business with her subversive, rebellious onstage persona,” Tsui says.

“This high-energy image translated into the comedic roles Mui was pigeonholed into doing, and she proved to be very good at them. But as we know now, she was much more versatile than that.

“Mui’s own rough-and-ready upbringing, which involved performing at night markets and dive bars when she was very young, probably helped her to play Fleur.

“You could probably trace Mui’s melancholy back to this part of her own life story, and it’s something which Kwan mined to tremendous effect in Rouge.”

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved industry.