Of the three Spider-Men put to screen in live action, Andrew Garfield's adaptation seems to receive the least amount of praise from the wider Marvel fanbase. As neither Sam Raimi's original nor the iteration incorporated directly into the wider Marvel Cinematic Universe, Marc Webb's The Amazing Spider-Man and The Amazing Spider-Man 2 and consequently, Andrew Garfield's Peter Parker are sometimes unfairly considered the awkward middle child of the three, not receiving as much acclaim. Though The Amazing Spider-Man excels in its actors' performances and emotionally gripping writing, one of its true strengths lies in its thematic cohesion. The film tackles one very impactful message: For Andrew Garfield's Peter, becoming a great hero means being a good man.

Uncle Ben

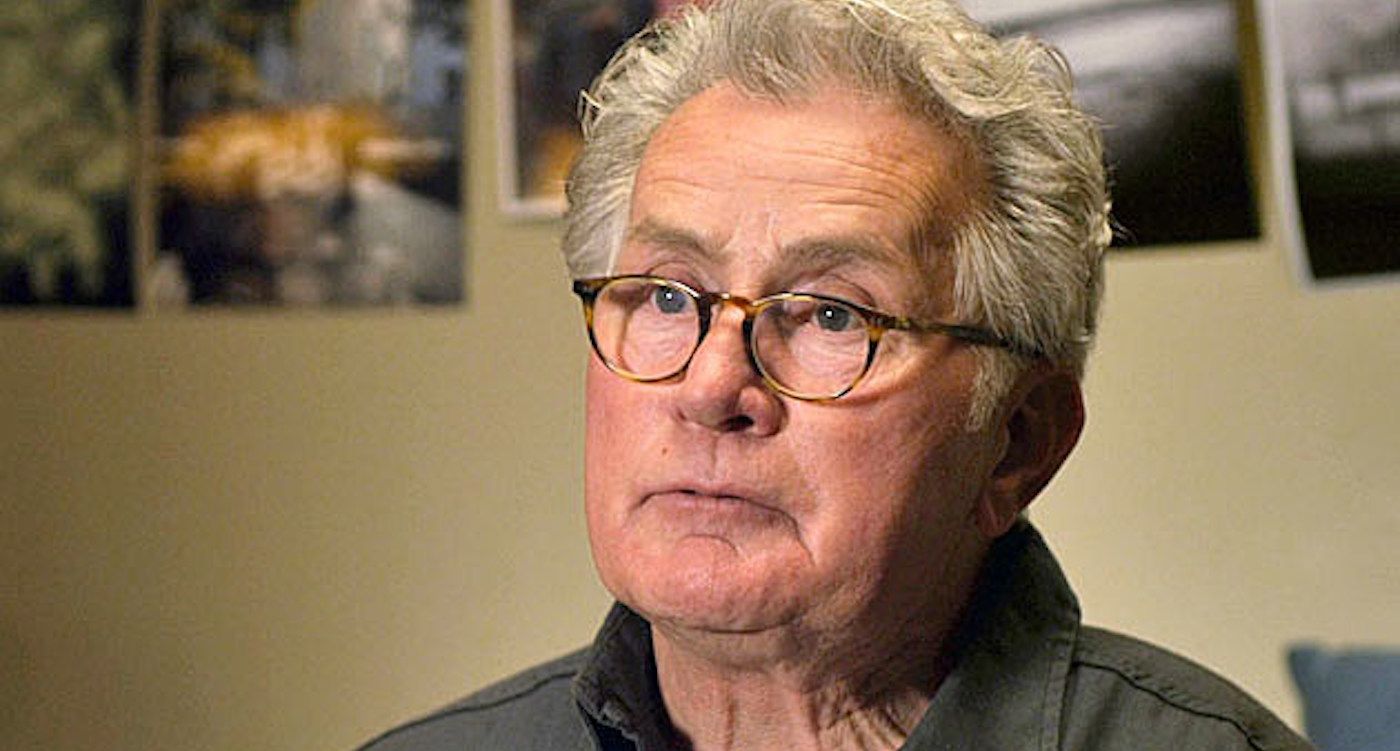

The Amazing Spider-Man's Uncle Ben (Martin Sheen) is the most well-rounded iteration of the character put to the screen so far. He is openly and unabashedly loving and playful towards Aunt May (Sally Field) in his introductory scene, modeling a positive relationship dynamic for Peter borne out of respect and affection. When Peter shows a deeper knowledge of the machinery flooding their house, Uncle Ben isn't combative or competitive about his nephew's superior intellect, even remarking later that Peter has outgrown Ben's education level at the age of 10. Ben Parker is also consistently emotionally available and vulnerable around Peter, recognizing his complicated feelings about Peter's parents' disappearance and helping him through those emotions, rather than pushing them away.

In the Spider-Man mythos, it's impossible to disregard what is arguably Uncle Ben's most impactful contribution: reinforcing the idea that "with great power comes great responsibility." Ben's first remarks on misusing power come when Peter, after receiving his powers, uses them to retaliate against his bully, Flash (Chris Zylka), at school. Ben shows up to take Peter home from the guidance counselor, chastising him for abusing his abilities for cheap revenge. When Peter later shirks his responsibility to take Aunt May home, Uncle Ben sternly explains to him that "if you could do good things for other people, you had a moral obligation to do those things... Not choice, responsibility." This affirmation summarizes this Peter's nuanced character arc, developing naturally from the action of the film rather than feeling shoehorned in. From Uncle Ben, Peter learns to grow beyond his selfish urges and use his power to help others, not just himself.

Gwen and the Female Gaze

In a world of superhero movies filled with bulky dudes written alongside egregiously neglected female characters, The Amazing Spider-Man stands as an encouraging outlier. In a term coined by feminist theorist Laura Mulvey as the "male gaze," Mulvey explains that many women in film are often defined only by what they represent to the male protagonist, often resulting in sexual objectification. They are deemed significant to the narrative because of their relation to a more developed male character, not as individuals themselves. However, The Amazing Spider-Man avoids many pitfalls of the male gaze in its treatment of its female characters.

Aunt May is no longer relegated to being a one-note fountain of wisdom to be physically tossed around by Spidey's villains, but instead is a complex character with her own hopes, fears, devotions, and flaws. Where this film truly shines, however, is in the relationship between Peter and Gwen (Emma Stone). Their connection is one of reciprocation and mutual respect, working as a central focus of the story rather than a narrative afterthought.

Gwen is a character as equally well-rounded as Peter, is just as (if not more) academically gifted as him, is never sexually objectified, and critically retains her agency throughout the entirety of the film. Garfield's Peter is never depicted to be in control of her, not dangled over a ledge by a villain for Spider-Man to save like Raimi's Mary Jane (Kirsten Dunst). Instead, Gwen makes her own choice at the climax of the second movie to use her scientific knowledge to synthesize an antidote to the Lizard's pathogen. This agency is further upheld as Peter willingly trusts her with his secret identity quite early into their relationship. This courtesy is not extended by any other live-action Peter Parker to a romantic partner, the reveal instead resulting from unwilling circumstances.

With No Shirt Comes Great Responsibility

A crucial point of difference to investigate when exploring healthy masculinity and the female gaze is how the three renditions of Spider-Man treat Peter as he is portrayed shirtless. A key misunderstanding some may have is the belief that shots of muscular men's bodies in superhero films automatically cater to the female gaze. In reality, they are often intended for male audiences. These scenes provide fuel for a male power fantasy, a vision of an idealized self. Where this differs from the objectification of women is while the women are portrayed as stripped of their agency, the muscular men are depicted as more capable than ever.

The female gaze inherently cannot exist in the same way as the male gaze, as the latter is a symptom of a sociological power imbalance. In Raimi's Spider-Man, Tobey Maguire's Peter miraculously wakes up and flexes his new physique in front of the mirror. The implied question to the audience is: "Wouldn't it be great if that happened to you?" By contrast, Andrew Garfield's shirtless scene contributes to a shared tenderness and vulnerability in his relationship with Gwen. It's an act not rooted in a muscular spectacle of toxic masculinity, but in genuine emotional connection.

A Vulnerable Peter Parker

Even beyond his scenes with Gwen, Garfield's characterization of Peter is allowed to express a wide range of emotions, avoiding the repressive stoicism of many other superheroes of the time. When Uncle Ben dies, Peter is shown breaking down. While Raimi's Peter experiences a similar moment, there is an element unique to Andrew Garfield's loss: a boyish element of fear and helplessness. This emotional authenticity and vulnerability subvert expectations of restrictive, toxic masculinity as seen in superhero films released around the same time. The male protagonists are rarely permitted to express any emotions other than anger or quiet sadness, as Tony Stark (Robert Downey Jr.), Steve Rogers (Chris Evans), and Thor (Chris Hemsworth) all suffer great tragedies in the first phase of the MCU, yet never cry. In this way, the emotional strength of these heroes becomes another manifestation of a power fantasy. Instead of an idealized body, the characters exhibit an idealized mental state, one impervious to any vulnerability of emotion.

Even when we catch up with this universe's Peter in Spider-Man: No Way Home, we find that he has somewhat regressed in his emotional development. He tells Tom Holland's Peter that he got "rageful" and "bitter" following Gwen's death, a loss he blames himself for. Garfield acts this scene with so much overwhelming emotion, not afraid to hide how much grief and sorrow Peter is still feeling. However, through the course of the film, Peter is reminded of his true strengths as a hero. He is open with his feelings towards his multiversal brothers, freely sharing how he always wanted brothers and telling them "I love you" at the start of the climactic final battle. In a moment of mythic, cosmic justice, this Peter is able to redeem himself by saving his brother from his own fate, catching MJ (Zendaya) from a fall similar to the one that killed Gwen Stacy. When he is able to de-power Electro (Jamie Foxx), the two have a moment to connect with each other, with Peter emphasizing to Maxwell Dillon that he was never a nobody. Peter is reminded in No Way Home that Spider-Man's ability to save and help others is much more valuable than his ability to defeat.

"You're My Hero, and I Love You"

Going back to The Amazing Spider-Man, following the loss of Uncle Ben, Peter becomes the worst version of what Spider-Man could be, indulging the dangers of toxic masculinity. Instead of helping others, he uses his powers for his own personal gain with his vendetta against Ben's killer. Peter Parker isn't a hero at this point, but a vigilante. His arc results in his most heroic moment in the movie not being a huge showdown with the Lizard, but when he saves a little boy from a burning car. Terrified in the vehicle as it dangles over the side of a bridge, the boy is empowered to climb out as Peter takes off his mask and gives it to him. It's one of the most emotionally resonant Spider-Man scenes ever, cutting to the core of what the character stands for.

Spider-Man isn't amazing just for his feats of superheroism, but for how he empowers others to be brave. This Peter's ability to humble himself and put the needs of others before his own is what makes him a hero, not just a crime fighter in a suit. Such a message can only be achieved through Andrew Garfield modeling this form of healthy masculinity, that his most important superpower isn't spider-related at all, but his simple capacity for kindness.