The 70s are often considered the second golden age of Hollywood. Emboldened by the success of Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider that closed out the 60s, many of the studios showed a willingness to entrust young producers, writers and directors to give a whole new voice to cinema. The result was a unique slate of classics from new filmmaking mavericks such as Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Robert Altman, Woody Allen, Bob Rafelson, Terrence Malick, Steven Spielberg, Hal Ashby, William Friedkin, George Lucas and Peter Bogdanovich, to name a few. How they differed from previous greats was through forgoing classicism for a closer association with reality, through more sounds or rock ‘n roll songs instead of scores, through more intimate plots in following a character more than their story and venturing off the sound stage and out into the real world.

Although many of those names were the lynchpin of new storytelling success for the decade, the 70s had many great films that also tapped into the rebel spirit of the new auteurs without continuing to receive a classic shine. Every decade has forgotten films, but the 70s are a treasure trove of movies that are rebellious, eccentric and alive, but no longer mentioned.

To create this initial list, I just had one criteria: the film had to receive less than 10,000 votes on IMDb, which seems to be a good barometer on whether or not a film has been left behind in the retrospective zeitgeist. With this methodology a few things were discovered. First, many of the films that could potentially land here were experimental with narrative, or grindhouse or foreign, which is of no surprise, of course. But more surprising was that many of the great American films from this decade that seem to no longer have a fervent following but were directed by an accepted auteur such as Altman or Ken Russell, frequently featured a female lead.

The great 70s films largely belonged to men, were made by men, and told the stories almost exclusively through the eyes of men and tried to de-code what it means to be an honorable man. They’re still great films, of course, but 70s cinema was the first real gender barrier for movies; all the praise and awards were going to The Godfather, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Rocky, The French Connection, The Deer Hunter etc. and it’s stark in comparison to previous decades where female-led films like The Apartment, My Fair Lady, The Sound of Music, etc., could still win the top film prizes through the 60s. The 70s is when the acclaim and prestige really became one sided and the vast majority of prestige pictures focused on men. I might argue that that was when the idea of a man’s picture and a woman’s picture really splintered as well. Since the 70s also gave us the idea of a blockbuster that forever changed film, with Star Wars, that divide increased in the 80s and we’re only now starting to see a return to prestige female pictures being made from major directors.

That’s not to critique the amazing films like The Godfather, Apocalypse Now, Badlands, Dog Day Afternoon, and more and more that came out in the 70s, but it is worth noting that most of the films on this list -- that did not receive initial studio support and no longer have the support of a voting system like IMDb -- feature women in the leading roles. The rest are foreign, fringe and naughty. Or in some cases, they are the directorial debut of a director who’d go on to have a cult following, like Walter Hill and Elaine May. Peruse some of the picks and sound off on which films you agree with or might want to check out, or which mega classics you think are overrated.

The Lickerish Quartet (1970)

Radley Metzger was a pioneer of erotica. While his contemporaries like Russ Meyer and Tinto Brass spent the 70s highlighting specific female features (Meyer the bosoms and Brass the butts), Metzger was making art that occasionally featured fornication. Don’t just take my word for it, Andy Warhol called The Lickerish Quartet “an outrageously kinky masterpiece” and UCLA has restored his film prints and held retrospectives to highlight his work. It’s academic.

The Lickerish Quartet begins at a European castle where a wealthy family watches an old “blue movie” (as one does with their family in a castle), then they travel down to a circus where they watch some daredevil tricks. They notice that a female motorcyclist (Silvana Venturelli) looks very similar to the woman that primarily featured in the dirty film they just watched. So, of course, they invite her back to their castle, where they talk about bike tricks, show her the naughty video and invite her to fulfill each of their fantasies, one by one. Meanwhile, she repeatedly asks, “who has the gun” and the patriarch of the family (Frank Wolff, who had small roles in both Once Upon a Time in the West and The Great Silence) has flashbacks to his time in war. Yes, there’s sex and there’s some goofy fantasy music, but what makes Lickerish Quartet impressive—and one of the few films of its kind where you can watch for cinematography, story and production design and still hold your snobby cinephile card—are the imaginative set-ups, editing and set changes (a library transforms into a dirty dictionary, for example). You might get hot, you might have a laugh, but you’ll also feel bad about war and parents.

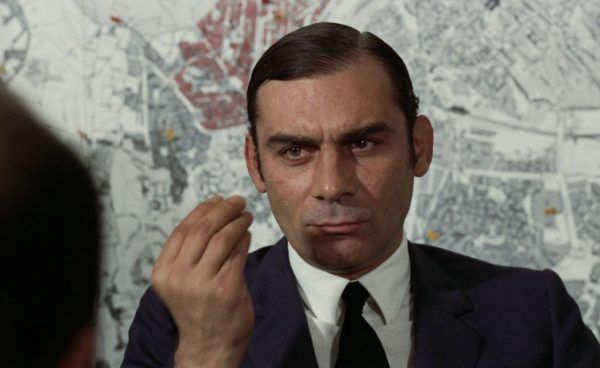

Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (1970)

Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion is the rare masterpiece that I'd also love to see an updated remake of. Its governmental concerns are so timeless, so ripe, so woven into the past and future fabric of corrupted governing society. Donald Trump once boasted that he was so popular with his base that he could shoot someone on Fifth Avenue and never suffer any consequences. Well, that's this as a movie, except far more intelligent, curious, and concerned by what that open admission actually means.

A Citizen Above Suspicion introduces the Roman Chief of Police (Gian Maria Volonte) as he enters the apartment of a lover who asks how he'll pretend to kill her tonight, except instead of engaging in their usual role play he does kill her; he leaves a mess of clues on purpose, curious to see if his status, which is what the woman was attracted to, could actually save him from any repercussions for a capital offense. The Ennio Morricone score, which is just a repeated theme composition, includes a jaw harp blast which lets you know that it's okay to find the humor in everything that unfolds. But, though the social commentary and satire itself is very strong, the true mastery of Elio Petri's film is in how he uses the flashbacks between the Chief of Police and the murdered woman, Augusta Terzi (Florinda Bolkan). We see her set a trap, unbeknownst to herself, by being bored one night and drunkenly calling the police station to bate whoever answers by describing herself being nude in her apartment with an intruder and she's curious if anyone there would save her or if they'd just let her be raped and ignore any future report. The Chief comes to inspect and interested in his power, she continues to push him to do things for the thrill of being too high in power to receive any knuckle-rapping.

Importantly, though Augusta is involved in this dance of the macabre, Petri never casts any blame on her for her demise. Bolkan performs Augusta as a woman who is rebelling against society but that rebellion pulls her close to men of power and also to men on the revolutionary side who want to snuff out said power; she's consistently stirred by breaking laws but immediately falls into a depression of awareness, where he captor does not.

An important distinction in Above Suspicion is who gets named and who doesn't. Most of the men in government positions are not referred to by name, but instead their rank, making them not human but the State personified. Those who are named are either victims or those who are under surveillance for their Communist leanings. It's an important distinction that post-Mussolini, Italy's fascism was allowed to continue, fester, and grow, simply due to the fear of Communism replacing it. Additionally, as Petri cuts between his attempts to be found out and his past relationship with Augusta, we come to realize that his sociopathic undoing is tied to what it most often is for men of power, a blow to their ego on their sexual virility. Though it's not said, we get the sense that the reason he commits this crime is so that he can move over to the Head of Political Police, to listen in on the revolutionaries associating them with Augusta's sexual preference because she sneaks away to make love to a Communist youth after rebuffing him on the beach.

This is a simply marvelous work of corruption, desire, and sociopathic tendencies that become entwined and fostered by power, and becomes corruptible. A room full of men flexing the type of power that allows such perversions of trust to continue. Nameless men, protecting their own, victims and truth be damned. Sound familiar?

The Music Lovers (1970)

The Music Lovers elicited this response from one of the all-time great film critics, Pauline Kael: “You feel (like) you should drive a stake through the heart of the man who made it.” The man who made it is Ken Russell. Historically speaking, The Music Lovers follows the doomed heterosexual attempts by famed composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky (Richard Chamberlain) as he rises through the musical world by turning his back on his homosexuality and takes part in a sham of a marriage. It’s about the power of music but it’s also about the destructiveness of withholding sex—from one’s self and from others.

After potentially outing himself to the veteran composers of Russia’s famed Mighty Five, Tchaikovsky chose his wife from a series of love letters that she had written him without ever meeting him. In his mind, because she only knew his music that is all that she needed to love him. But Antonia (an amazing Glenda Jackson) needed more than his music. She also needed sex to feel loved. That sentence might sound crass and Russell does sometimes present it as so, but it’s also heartbreaking. There is humiliation in both turning down someone for sex and in being turned down.

There is a magnificent scene on their honeymoon where Tchaikovsky specifically gets Antonia very drunk on a train so that he won’t need to have sex, but she still tries. She passes out naked on the floor of their train car and the bumps of the tracks make her body sway back and forth violently; Tchaikovsky looks in horror at her vulnerable body. It’s this horror of sexuality that perhaps provoked the stake reaction from Kael. For Russell, as a director, is anything but classical. He, like Tchaikovsky here, was new on the scene in 1970. And he radicalized what could be done with a historical epic. This isn’t David Lean. This is a film that re-enacts the visions we create when he hear music. And one that looks at an insane asylum as a breeding ground for, well, insanity. This is the most unusual and loud film to ever receive the brushstrokes generally reserved for adventure epics.

A New Leaf (1971)

Woody Allen and Mel Brooks receive most of the accolades for American comedies in the 70s, but Elaine May deserves to be mentioned as their equal (fittingly, Allen recently cast her as his wife in his Amazon series, Crisis in Six Scenes). The Heartbreak Kid is her masterpiece (and darn near a perfect entertainment) but A New Leaf was her fantastic start.

Leaf concerns Henry Graham (Walter Matthau), a trust-fund dimwit who has no real hobbies or knowledge. We meet him when he’s informed that he has no real money; he spent it all. In a last ditch effort to keep going to the country club and live high society he makes a bet with his Uncle that he could be married to a rich women in six weeks. If he succeeds, his debt will be forgiven and eventually he’ll kill off the bride soon after the ceremony to receive her inheritance. May herself plays the potential bride, a clumsy and bookish woman who no one talks to at the high society club.

A New Leaf is a classic Preston Sturges-inspired slapstick comedy with a devilish lesson by the end of its run time. Matthau’s deadpan delivery is perfect to represent an untalented but entitled oaf and as the 70s created the framework for growing income disparity, his foolishness is extra cutting now. But the sinister satirical twist that May has up her sleeve is the idea that the reason men so easily dispatch of women and relationships is because they’re seeking someone who will give them a legacy. For many, that’s an heir to run a company with their name on it, but for Matthau’s fop, it’s having a new species of plant named after him. Will such a gesture make him turn over a new leaf and think of someone other than himself?

The Boy Friend (1971)

Ken Russell gives Sandy Wilson’s Broadway smash The Boy Friend some movie razzle-dazzle. The play itself is about the roaring twenties and two young people falling in love against their parent’s wishes. This adaptation concerns an understudy (Twiggy) at a struggling 1920’s London playhouse, who’s thrust into rehearsals after the star (a Glenda Jackson cameo) suffers an injury for the production of, you guessed it, what will become “The Boy Friend.” Many of Wilson’s popular songs remain here, with a side story about a movie producer being in the audience looking to cast the next big thing, and the understudy beginning to fall in love with the male lead (Christopher Gable) as he helps boost her confidence throughout the rehearsal.

The Boy Friend is overlong but has some of the most amazing set and costume designs of any musical. Because this is Russell, those designs create daydreams of the performers as well, not just the production. It’s a dazzling movie for design. And Twiggy, the model, is quite natural as the unnatural star that has the it factor that the movie producer is looking for. Russell said that he made this film as a pallet cleanse for the tumultuous and studio meddled The Devils (see below). As such, it’s easy to see why it’s overlong, as Russell probably just needed some shiny joy in his life. Fans of La La Land will find a few set design nods here.

The Devils (1971)

Ken Russell’s The Devils is less forgotten and more just really fucking hard to find. It’s consistently requested to be added to the Criterion Collection but Warner Brothers seems hell bent on never EVER letting go of the rights. The studio has blocked the release of a Blu-ray, allowed BFI only to show it in England if it’s listed as an educational experience and the version that myself and many film fans have seen, stateside, comes directly from Martin Scorsese’s own collection, which he lends out for an occasional screening (just to hype you up). To add to the intrigue, Guillermo del Toro has accused WB of 40+ years of censorship by never allowing it to hit home video. Now this is the studio that widely released The Exorcist—which included a scene of a possessed pre-teen girl stabbing her vagina with a crucifix and then forcing her mothers face into her privates while grumbling, “lick me”—just two years later. So in a day and age when studios’ back catalogues are widely available, why does this film sit under lock and key?

The Devils centers around a vain priest (Oliver Reed) and the hunchback nun (Vanessa Redgrave) who lusts for him so deeply that she accuses him of witchcraft and other nuns at the convent join in on the accusation because the accusation allows them to behave like they’re under a sexual spell and thus they’re more free to practice their desires than the church will allow. It’s a loony masterpiece, as many of Russell’s films are. And when the nuns indulge it brings out the anarchic and chaotic side of the auteur. This is one of Redgrave’s greatest performances and it’s an interesting critique of religion and the suppression of desire. Now, the film is so hyped from its own suppression that it’d probably seem tame by today’s standards, which makes WB’s behavior even stranger (in WB’s mode of thinking, blasphemous presentations thrust upon a child in possession are more okay for the public, but blasphemous presentations that are being faked by a convent are not).

Note, there are two masturbation scenes that were cut from the theatrical print to receive a brief X-rated release in both the UK and the USA, oh which I’ve seen one, and it’s not graphic but is both unsettling and darkly humorous, calling into question whether all Christians practice their religion to make pure their heart or because it gives them the ability to control others. Perhaps it’s the obvious desire of outside cinephile sources like the Criterion Collection to release that footage as a bonus feature that keeps this film suppressed. Or maybe, like Birth.Movies.Death notes, it’s just some old crotchety executive who has a personal vendetta against the film and we just need to wait for that person to die off (like many backward approaches to thinking these days) and we’ll finally all be able to decide for ourselves if we can handle this movie or not. If you ever see this film listed in your local listings for a one-night showing, go.

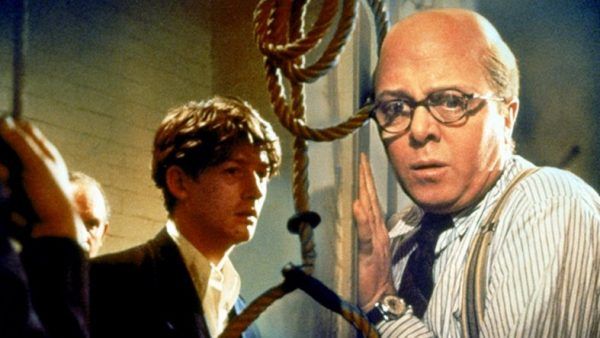

10 Rillington Place (1971)

Attn: Murderinos, 10 Rillington Place is a riveting and uncomfortable forgotten true serial killer tale in which the most huggable man from our Jurassic Park/Miracle on 34th Street childhood, Richard Attenborough, gasses women, has sex with their unconscious bodies, strangles them, buries them in the yard, and frames someone else for it! Something that grounds this film, rather than sensationalizing the acts, is how it repeatedly shows how patriarchal society (and veteran-worshipping society) allows the killer to operate with ease. He earns trust through his educated voice and his declaration of previous medicinal practices. His tenants (John Hurt and Judy Geeson) are a young, very poor couple with one child. The wife wants an abortion because they don't have the money for a second child because he's illiterate and the only one able to join the workforce. John Christie (Attenborough) is their neighbor and he is able to order his wife (Pat Heywood) to leave whenever necessary for his "work" as the sole provider himself. It's his war record that keeps his previous arrests suppressed. And it's the system that favors vets, educated men, and a lazy police force that allows him to continue even after bodies are discovered.

Attenborough is nauseating and riveting, Hurt is magnificent, and director Richard Fleisher (The Fantastic Voyage) takes well to Britain's kitchen sink realism after Hollywood discarded him after a few studio flops. The sadness in Attenborough's posture when he pours a poisoned tea that he won't be able to use for rape and murder because the plumbers have come over is such a nice attention to the amount of control this man is used to having within his house.

Audiences weren't as used to serial killer films in 1971 as they are now, so starting the film with a beloved actor dragging an unconscious woman to the ground to have his way with her, was shocking in 1971 so it'd make sense that Fleisher would focus on two grizzly acts and the miscarriage of justice and not force the audience to endure more killings from the true story. But now that we have a serial killer obsession in film/tv those final 10 minutes of miscarried justice could be its own movie; how this monster continued and why the UK abolished the death penalty because of it. Still, even though there's a rush through a trial at the end, this is expertly paced, nauseating, and beautifully performed.

Wake in Fright (1971)

Australia’s Wake in Fright is the most artistic Hangover-styled movie and my personal nightmare: being surrounded by a horde of degenerate men who drink, gamble, fight, dismiss women, and shoot animals for sport, with no available option to leave them behind. Gary Bond is a schoolteacher who makes a bad gambling bet and is then marooned in a town full of drunk and violent men (led by Donald Pleasance) who attempt to force him to be just as drunk and violent as them.

This story of male malfeasance is more frightening than Deliverance because these men are more identifiable, and the desire to sexually dominate other men is hinted at rather than outright shown. The orange desert expanse is lensed beautifully. But be warned, the kangaroo hunt is vomitous, it looks real because director Ted Kotcheff used real footage that he’d found; this was to confront his audience, with growing illegal kangaroo hunts occurring for manly sport, and was integral to increased regulations, but 40 years later without that awareness of the time, it’s incredibly difficult to watch, so knowing that beforehand is not only a necessary warning but also necessary to know the reasons it was included in the first place. And the negative traits of men in groups making the worst choices over and over is timeless. Though he attempts in numerous ways, the schoolteacher can't seem to leave them behind; it's like he's in a sand globe.

Kotcheff is most well-known for directing the first Rambo movie, First Blood, but he would numb these fraternity themes for American party movies such as North Dallas Forty and Weekend at Bernie’s (!!). Even though the men in Bernie’s are hanging out with a dead guy, I'd much rather kick it with those dudes than these monsters.

Little Murders (1971)

I was introduced to Little Murders, a hilarious satire of marriage fever, through a friend who was getting married. She wanted the person who was overseeing her vows to watch the clip of Donald Sutherland’s pastor as he delivers a wedding introduction about how the “business of marriage” deserves “an abandonment of ritual in the search for truth.” The subjects that Sutherland talks about while Elliott Gould and Marcia Rodd await to marry are how many of the weddings he’s presided over have ended in divorce and the many reasons why those failed marriages took place; masturbation, drugs, disinterest. It’s truly a mesmerizing, hilarious and yes truthful analysis of rituals and marriage and how everyone’s reason to marry is “all right” and so are their decisions to leave, because as much as we like to look at marriage as a melding of two identities, that’s the untruthful version.

Watch the monologue here and if you agree that this is a pretty groovy speech, give Alan Arkin’s directorial debut a spin. It’s full of wit, immensely intelligent, although it does take an odd detour for the third act, it’s one of the funniest films from a decade that was moving from the swingin’ 60s back to timeless rituals. As for the murders? Like many films on this list, it’s a time capsule of the extremely dangerous and grimy New York ‘70s. And as for the wife-to-be who introduced me to the film? She’s still married and putting the finishing touches on a Hal Ashby documentary that should begin screening in 2017. And for anyone reading this list, that’s a must look for, because Ashby is perhaps the most forgotten major auteur of the 70s.

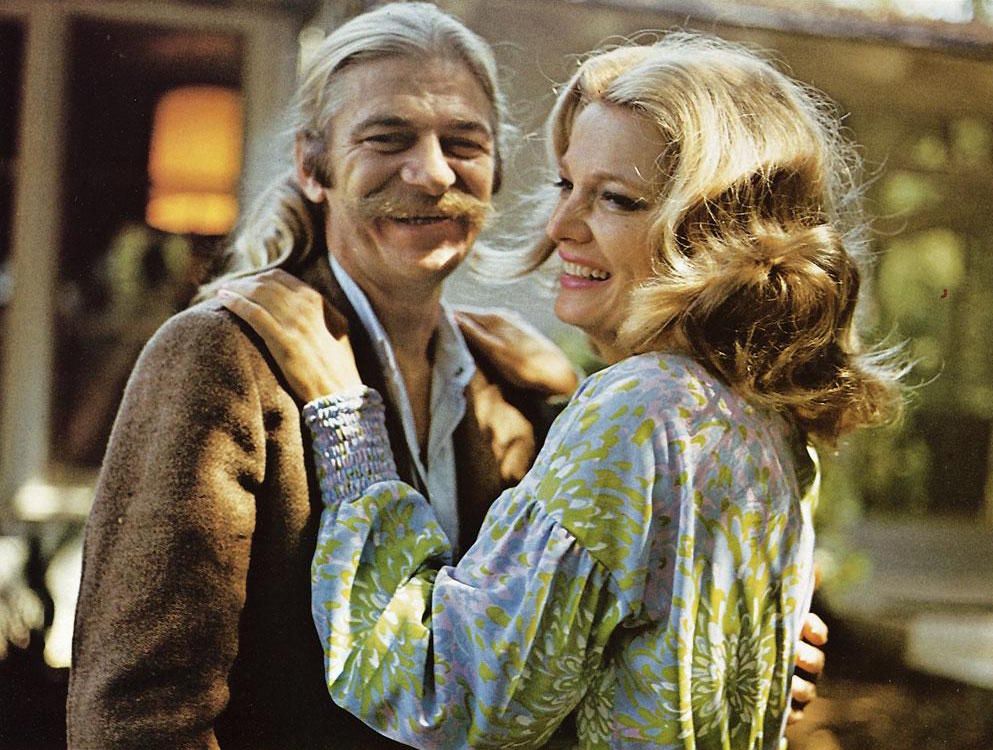

Minnie and Moskowitz (1971)

Minnie and Moskowitz could easily be retitled as “Men Who Yell at Gena Rowlands About Why They Should Be an Item”. But with John Cassavetes script, the yelling is fun. Exhibit A, Zelmo Swift (Val Avery), a funny-named rich guy who’s “terrified of women” and a really bad date conversationalist but pure movie gold for the date from hell who goes on and on about her appearance and how “terrific” she is without ever allowing her to speak. Exhibit B, the wildly mustached valet, Seymour Moskowitz (Seymour Cassel, Jason Schwartzman’s dad in Rushmore). Moskowitz rescues Minnie from the end of that date and then immediately tries to take her out on a hot dog date. Unlike Zelmo, he does ask her questions but Minnie barely responds.

Minnie and Moskowitz introduces its two main characters while they have a separate conversation about cinema. Ultimately, this is an insight into their worldview. Seymour sees movies as an escape and Minnie sees them as false hope (“They set you up. And no matter how bright you are, you still believe it.”). Cassavetes follows the meet cute/knight-in-shining-armor formula of a movie romance, but instead has “the prize” be a woman who’s given up and close to comatose in concern to any emotional feelings at all. Minnie represents how ugly the world can be and how sad movies can thus become for giving hope and Seymour represents how alive the mundane can become with just a mindset of looking for entertainment. One is successful; the other is a step above a bum (but he’s also kind to bums and kind of mean to successful people). Seymour’s pursuit isn’t exactly romantic but romance does feel possible between them and that’s this movie’s journey: presenting the possibility of romance instead of the movie version where romance is sealed by the end credits.

Images (1972)

Robert Altman’s claustrophobic woman-going-mad tale was delivered a disservice by film critics in 1972 and essentially snuffed its wide release. Susannah York won Best Actress at the Cannes film festival that year, but the largest papers in New York refused to cover it and the few reviews out of the New York Film Festival killed its chances of further distribution. It’s strange to think how coldly critics received Altman’s film, but he had just made M*A*S*H and McCabe & Mrs. Miller, two involving and straight narrative masterpieces and Images probably seemed like a mess at the time. But watching it now, after many of us have seen other deranged femme films, such as Opening Night, Mulholland Drive, Black Swan, Queen of Earth and many more, it’s a rather natural watch and perfectly executed by York, Altman and the cinematographer, Vilmos Zsigmond.

Essentially, Images is a visual retelling of Ingmar Bergman’s Persona. In Bergman’s film, a nurse confesses a sexual event to a mute patient and then feels that that patient has a power over her because she knows her darkest secret. But whereas Persona used a lengthy monologue for that confession, Images uses, you guessed it, images.

In Images, it’s a married woman who knows she’s cheated on her husband; the first man she cheated with died in a plane crash, and now he’s haunting her in their hunting summer home. A man who lives nearby senses her damage and thinks she’s sending off rape fantasy signals, so he visits her while her husband hunts. Her summer retreat is a haunted house of men’s taunts and sexual desire (both from the dead and deadly). She thinks she kills all of them, but which man does she actually murder?

This is one of Altman’s most stunning exercises in mood and camerawork (it’s also one of the weirdest and most exciting scores from John Williams, full of twisted nerves). Foreboding deer heads, whispered narration, piano planks, camera movement that shows a murder in her mind and then can reveal the truth in the same frame, yes, Images barely received a release, but you can see its influence on future filmmakers like the blood stain of a dead body dragged from the kitchen.

Sounder (1972)

Martin Ritt’s adaptation of William H. Armstrong’s symbolic young adult novel could really use a re-master. As it currently stands it has the look and sound of an old TV adaptation, but don’t let that you discount the film. Sounder is a powerful film about the fine line that a black family must walk in order to be successful in society. After another non-successful hunt, a father (Paul Winfield) steals some ham for his children and is jailed and sent to a chain gang and his wife (Cicely Tyson) and eldest son (Kevin Hooks) repeatedly hear from the shopkeeper, sheriff and local women who send them their laundry, how they “went out on a limb” for them as a family. It’s heartbreaking to watch how the Morgans are treated as though they’re supposed to feel shame in their work because it’s a perceived privilege for them to be working at all and thus the town’s desire for gratitude now turns into a desire for an exchange in disgrace.

Tyson shows an enduring strength to be judged only by her work, she does not sermonize in the matriarch role, and Sounder is quietly feminist as she attempts to instill her own separate honor, outside of the family unit. Hooks eventually runs off with his trusted dog to locate which chain gang his father is on. He stumbles into a schoolhouse with a teacher who doesn’t judge him by his father’s crime and offers him assistance in learning to read. What makes Sounder a successful adaptation of a beloved book is Ritt’s use of sound, his trust in the performers to perform the unsaid and to leave the thesis of the book never stated outright, but instead it reveals itself to the audience with subtlety. Sounder is a very adult adaptation of a popular children’s book, handled with grace and dignity.

Heavy Traffic (1973)

Ralph Bakshi’s (The Lord of the Rings) non-wizard animated films are hard to watch and harder to recommend, but they’re also essential viewing for anyone interested in viewing 70s New York from the garbage can. Fritz the Cat perverted the counter-culture movement and Coonskin is an ugly look at urban racism, for instance. Heavy Traffic is his most personal film, about a young cartoonist wandering the New York streets as a way to get out of his abusive household, and as such it doesn’t feel like he’s trying to provoke or intimidate but rather confess that he’s seen a lot of tough shit in his day but somehow still lived to see many days. But at the end of the tunnel, which is full of prostitutes, strippers, hoods and bums, he loves his hometown. It’s the city that never sleeps because there’s so much seedy stimulus. Consider yourself warned, his films have no room for sensitivity, rather they're an endurance test. Just how he views his city and home life.

Heavy Traffic is a fever dream, a 70s Dante’s Inferno, and to watch it is to add additional context to Travis Bickel’s observance in Taxi Driver that someone could become so over-stimulated by cheap pleasures that they’d request for “a real rain to come down and wash all this scum off the streets.” In fact, when Martin Scorsese was shooting Taxi Driver they had to halt production for a brief period when a protest over Bakshi’s Coonskin resulted in a smoke bomb going off in the streets outside the theater. Scorsese sent the footage to Bakshi who said he “didn’t know whether to laugh or to cry”. Somewhere in Heavy Traffic lies the beating heart of an artist who believes that laughing while crying is the only way to really wash things away.

Torso (1973)

Torso is an Italian slasher that sets most of the rules that would be established later for American slashers. The leering male gaze makes everyone a suspect when the student bodies start to pile up and it’s the free sexual beings who are killed off one by one. There is so much nudity in the beginning portion that Sergio Martino’s film approaches misogyny, but the giallo master sets up a fantastic payoff. But by the end, after hearing all the ogling town conversations the working class men are having about the female students who’ve rented a villa to hide away from the killer who’s hacking up women at off-campus parties, the killer's obsession with doll parts starts to make sense in how female bodies are used.

His motive is silly, but a grown man's manhood was stunted in a youthful moment of asking to play a game of I'll show you mine if you show me yours, that's thwarted by something tragic that happens with a doll. And on the college campus, at the free love bordello, and at the picturesque villa, when ample nudity happens, it's women who are in charge of their bodies: willingly partnering with a lover in the backseat of a car, dancing in undress in a hippie dirge, lounging naked on a sofa allowing men to fondle their breasts while they smoke a cigarette but telling them to stop when they try to go further, and, most brazenly, when alone, nude sunbathing topside up at the villa. And then suddenly, when the killer arrives at the villa, Martino flips the movie on its head and gives us the ultimate final girl scenario before the final girl had even become a trope.

In each instance of nudity, women are in control of their bodies. It is leering, and yes, the lesbian scene feels more like a producer saying give one to the audience, but by the end, I think the excessive nudity is hammered home as having a point. Dolls are something that young boys cannot play with unless the girl's owner gives permission. And frequently that is not the case. The lounging nudity has more to do with the stillness of their adult bodies in a natural state, reduced to doll parts if a man sees them in such a pose. (The final bit of dialogue from the men in town is that those beautiful women wouldn't even talk to them because they're uneducated; again, a way that women have more agency during an era where pre-marital sex is the new normal but women’s roles in romantic and educational pursuits are changing alongside it, giving them more agency).

But it’s the final 30 minutes that makes Torso an all-time great giallo. The murders start to happen off screen as the killer stalks the villa, so instead of murderous scenes creating tension, it’s a prolonged sequence where each floorboard creak, each hold of the wooden barrister, is given immense weight. It's one of the most prolonged-intense sections of a horror film I've ever seen. And though the Final Girl scenario goes different from the future rules, Martino has immense camera tricks up his sleeve to disorient the viewer.

The Iron Rose (1973)

Jean Rollin’s The Iron Rose is The Exterminating Angel of morbid lust movies; two young hotties go into a graveyard and can't find their way out. Is it a metaphor for marriage? Maybe.

Two French strangers (Françoise Pascal and Hugues Quester) meet after he recites a macabre poem at a wedding. Boy asks out girl, girl says yes, so he punches a tree out of excitement. They meet at the train yard the next morning and chase each other from locomotive to locomotive. It's cute. He suggests wine but the girl doesn't know that he wants this picnic to be in a graveyard because it's quiet. Against her reservations of location they do end up hooking up in a crypt, of course, but after their love session lasts the length of an entire candle they emerge in the darkness, start to bicker and abuse one another until he kicks an iron cross, she lies down on a grave and perhaps becomes possessed. Still, even though she's saying crazing things about the Day of Death and crawling on all fours, boy will still make out with girl on top of skulls and femurs if she’s willing.

The trap is sexuality and how men force women from carefree fun into situations that they'd rather not be in. This might be a metaphor movie or it might just be a single location cheapie. I think it's both. Rollins’ macabre mood and ketchup and mustard sweaters lend this a bit of a Scooby Doo vibe (heaving cleavage aside). Through in a lovely score and you’ll wish horror did meet cute death trips more often.

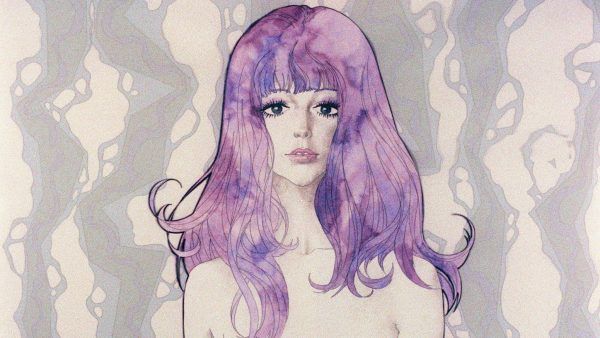

Belladonna of Sadness (1973)

In this animated psychedelic pop fantasia of devilish sensory overload, an evil feudal lord assaults a village girl on her wedding night and proceeds to ruin her and her husband's lives. After she's eventually banished from her village, the girl makes a pact with the devil to gain magical ability and take revenge against everyone. Belladonna of Sadness is equal beauty and grotesque and was hugely influential for the alternative Japanese animation adult filmmakers, like Satashi Kon and Mamoru Oshii, to come. What does make Belladonna unique, is that it takes something that could have been a straight medieval horror show and scrubs the darkness to allow room to lounge in ecstasy, which makes the moments of oppression that more cutting and the reprieves that much more of a relief. It’s truly something that the Devil elicits more sympathy than mortal men but it’s because at least he understands her desires and her desire for revenge. Understanding is something men cannot afford Belladonna of Sadness.

It’s hard to describe this orgy of excess without sounding crude, so instead, I’ll just use Acid Mother's Temple song titles to wrap up this blurb, since psychedelic watercolor and psychedelic rock are the long flowing hair of this narrative; the pastels standing up to the darkness as:

“Hello Good Child”

“Sweet Juicy Lucy”

“Third Eye of the Whole World”

“Interplanetary Love”

“Pink Lady Lemonade”

“Goodbye, Big Asshole”

Yep, that sums it up better than “far out” could.

Blood for Dracula (1974)

Count Dracula was always a bit of a seducer, but Paul Morrissey (and producer Andy Warhol) gave us a hilariously impotent Dracula (Udo Kier) in Blood for Dracula. This Dracula’s body is growing incredibly weak because—after centuries of feeding on virgin necks—it’s become harder and harder to find virgin women to drink from. His assistant suggests they go to Italy where families still have staunch Catholic values and thus the women will be pure. Warhol’s sex god Joe Dallesandro (always the candy, never the actor; he brandishes a thick Brooklyn accent in Transylvania) has taken it upon himself to take the virginity of every woman in the Italian countryside to starve Dracula out. Blood for Dracula gives a different meaning to a wooden stake piercing the heart of Dracula. Here, morning wood is literally killing the Count.

While it’s easy to laugh at an impotent seducer, there’s certain sadness in Kier’s performance; with increased sexual freedoms we lose classical society and Kier’s Dracula is a physical representation of that slow death. This is a man who could live forever as long as he lived in an era of purity. For centuries, Dracula was a sorcerer of sexuality and men had to hunt him down and physically impale him to protect their pure women. Now any man with six-pack abs can thrust his way through town and weaken his powers.

Celine and Julie Go Boating (1974)

Jacques Rivette’s three hour (plus!) art-house behemoth, Celine and Julie Go Boating is two things for me, it’s the most realistically dreamlike film I’ve ever experienced (including the disintegrating build-up to the big finale) and also the best portrayal of lucid dreaming (where the dreamer can affect the dream to have an outcome they want, because they are aware they are dreaming).

Celine (Juliet Berto) and Julie (Dominique Labourier) are two women who become linked in action and their identities meld. If one reads a book about magic, the other is a magician. If one underlines book passages with red ink, the other paints in red. After a series of many linked objects and actions, the young women find themselves in some ghost-lesbian-murder-mystery that plays on loop. A house with a mourning father is stuck in limbo where his stepdaughters daily re-enact a murder. Celine and Julie experience this in the foreground and, as we do in dreams when we’re aware we’re not partaking in what we’re seeing, begin to test how they’ll be noticed or what they can get away with in the presence of this scene.

What occurs is curious, funny, and delightful. But what aids Celine and Julie to maintain the dreamlike atmosphere is that the viewer forgets so much of the coded set-up once they’re in the house. Just like a dream, you’re only left with the fragments you latch onto and attempt to explain.

Score (1974)

Yes, this is X-rated, the plot is pretty bare and there is a girl on girl strap-on scene and a man on man blowjob scene, but I dare you to find a film that is more at ease with the joys of life than Radley Metzger’s Score. The film is about a swingin’ married couple (Claire Wilbur and Casey Donovan) on the prowl to seduce a prude married couple for a night swap of partners of the same gender. Even if you yourself are prude, there is a lot to appreciate in Metzger’s filmmaking abilities. The score is bouncy and alive. The performances are solid. And his mis-en-scene composition is revelatory. Metzger was a fantastic director who wasn’t stuck in soft-core, but rather he knew that soft-core could be an art form. Most portraits that have hung in museums for decades were nude. Why should film not present it artfully as well? Sex and shame might be built into religion, but it shouldn’t be built into our art.

Score isn’t meant for a ten-minute fast-forward to “the good parts” because the seduction and conversations are actually the best parts. It’s a lovely 90-minute film that features intelligent and witty conversations about sex. Some of those conversations happen while two women talk between a lava lamp aquarium because film conversations should always be pleasing to the eye. What’s really fun about Score, though, is how inclusive it is. Every character works at getting the other off and everyone has smiles and the score is a blast. Don’t let the intro sentence scare you; this film is not very explicit. If you can handle hearing people talking a lot about sex and marriage inside a lovely 70s styled apartment on the Italian villa, and then have a few minutes of sex, you’re really in for a treat. You’ll smile thinking about this film. You’ll hope to meet anyone so excited to be alive as the repressed new couple (Lynn Lowry and Gerald Grant) are as they leave the villa to convert someone else to their new free ways of thinking. Sex can be fun. The pursuit can be fun. And Score is so much damn fun there’s nothing at all you could feel guilty about in watching it.

Hard Times (1975)

Hard Times gives a neo-Western retooling of the standard Great Depression and boxing tale. There’s no girl to get by the end, there’s no big prize to set everything straight; there’s just some extra scratch and respect earned. This is cult director Walter Hill’s (The Warriors) first film and it’s very assured. He presents it as a classical tall tale of the stranger off the boxcar (Charles Bronson) who can beat every man in a fair fight, but he slowly reveals that there’s not much to win.

By this time Bronson had already been retooled as a grindhouse revenge star, and there’s an expectation that this film would be similar, but Hill is most interested in the business side of illegal fights; how trust is renewed by earning the literal cash payback and not through violent retribution. In Bronson, Hill gives “Speed” (a great, blustery James Coburn), a promoter who’d usually use his lying mouth to get out of debut, a new method of honoring himself: keeping true to his word through thankless work.