Prince of Wales visit to India 1921-22: the most disastrous royal tour ever

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

To see him, to meet him, is to submit to his magnetic personality. He is more than a prince. He is the servant of peace. He is the greatest antidote in the world against unrest and disorder.”

It is hard for those who have grown used over the years to regarding him as a self-centred, bitter and envious man with a high sense of entitlement and a penchant for the ideas of the far right to see the Duke of Windsor, briefly King Edward VIII, described in this way.

But this was February 1922, 15 years before his abdication, and the then Prince of Wales was a popular celebrity – probably the first British royal of whom that could be said. He was young, slight, blond and blue-eyed, seemingly rather diffident and shy, and invariably portrayed as both “charming” and “sporting”. One could almost describe him as the Princess Diana of the early 20th century.

When the extravagant praise just quoted was offered to a packed House of Commons Edward was several thousand miles from London, roughly half-way through an exhausting four-month tour of India. He did not want to be there, but he had had no choice. The British government, with the palace’s agreement no doubt, had decided he was uniquely qualified to carry out an urgent and difficult task. It can be summed up quite simply as Saving the British Empire.

The Empire might have been “victorious’ in the First World War, but it emerged from the conflict needing to answer urgent questions as to what its future identity might be. Neither the French population of Canada nor the Irish in Australia had been all that willing to risk their lives for the British; and the nationalist movement in India had made it clear that their contribution to the war effort would come at a high political price for the Raj.

There could be no going back to a pre-1914 Imperial order, so for the Empire to survive and prosper it needed to be re-branded and refreshed: and who better to be the symbol of this Imperial propaganda campaign than Prince Edward. “The appearance of the popular Prince of Wales”, Prime Minister Lloyd George said, “might do more to calm the discord than half a dozen solemn Imperial Conferences.”

The year 1919 found Edward in Canada; in 1920 he was sent to Australia and New Zealand; 1921-22 saw him in India; there were trips to the United States in both 1923 and 1924; and, finally, in 1925 to South Africa and Argentina.

There had been occasional royal tours before this, most notably a visit to India in 1875 by Edward’s own grandfather. But what was new about the post-First World War tours was the element of publicity. There was an accredited press team throughout, and almost every stop was a photo-opportunity. The crowds who came out to see the heir to the throne were loyal subjects of the crown; but they were also becoming modern consumers of royalty.

Of all his “propaganda” tours the most challenging for Edward was undoubtedly that to India. The political situation that he sailed into in the late autumn of 1921 was extraordinarily fraught. The Punjab had been in a state of violent upheaval for nearly three years; and there was still a pall of outrage hanging over the north-west of the country from the massacre in Amritsar two years previously.

He had spent the war trying desperately to persuade his father, King George V, to let him fight; and he hated the fact that being heir to the throne meant he was protected from any danger

Draconian new laws of censorship and summary justice had been introduced; and there was widespread frustration with how meagre were the democratising” changes introduced by the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms of 1919.

Most threatening of all from a British government point of view was the inauguration earlier in 1921 of Gandhi’s non-cooperation movement, which was followed by a formal decision of the Congress party to boycott Edward’s visit. This led to an intense debate in Britain as to whether the royal tour should be called off. Would it serve to further provoke nationalist opinion, worried some on the right? Would Edward be safe? While for many on the left the very idea of such a tour was preposterous.

For HG Wells it was “propaganda of an inanity unparalleled in the world’s history”; and for EM Forster, who already knew India well and disliked how the British behaved there, Edward’s proposed visit was simply “impertinent”.

The novelist spent much of 1921 in the small central Indian state of Dewas, employed as Secretary to the Maharaja. “About the Prince of Wales’s visit”, he wrote in early November, “it is disliked and dreaded by nearly everyone… his visit will be worse than useless.” Edward himself was receiving letters from India urging him not to come. This is part of one from a Congress leader in Bihar: “Noble Prince, if your Royal Highness means to do any real benefit to India, it will be done by cancelling the proposed visit, and directing the authorities here to devote the money raised for the visit in feeding the hungry and clothing the naked.”

The Prince of Wales would have been only too happy to oblige. He was exhausted from travel: he was worried about being a target for anti-British sentiment in India; and he resented having to be parted yet again from his lover, Mrs Freda Dudley Ward. But the decision was not his to make. As a consolation he was provided with a friend and confidant for the duration of the trip – his naval cousin Lord Louis Mountbatten, whose often candid diary is a key source for understanding how fraught and uncomfortable the tour proved to be.

The non-cooperationists of Bombay were ready and waiting for Edward when he arrived on the 21st of November: and even Mahatma Gandhi’s presence in the city could not prevent the protests turning violent. Riots continued for three days, with casualties on both sides.

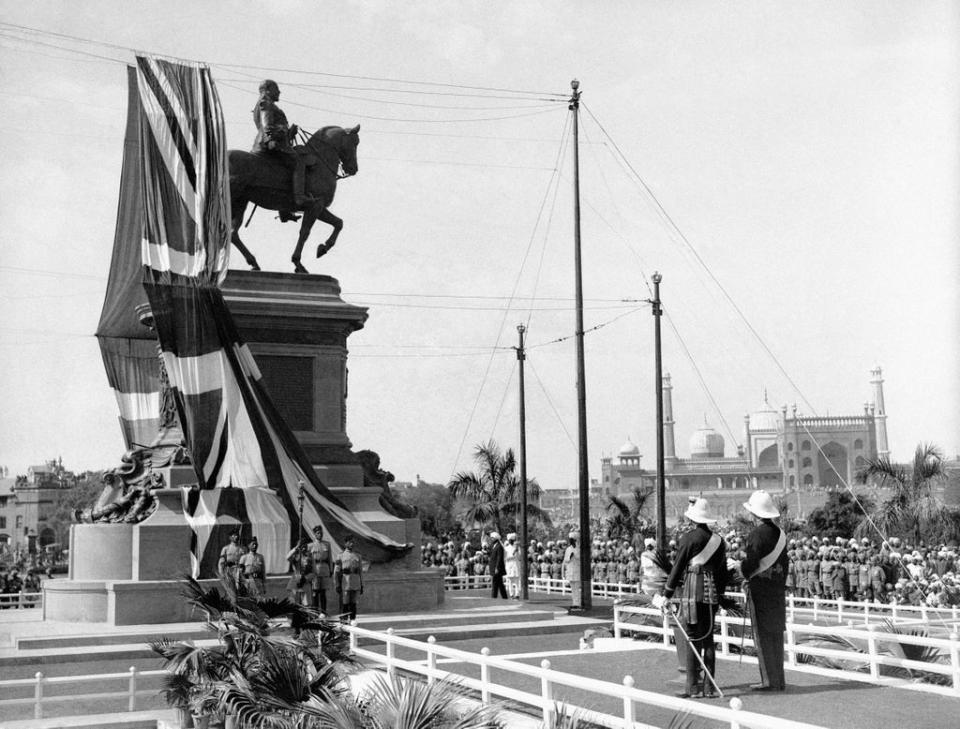

Bombay proved the first of many places in British India that was to experience violence and death as inescapable corollaries to the privilege of a royal visit during that winter. But Edward’s formal welcoming party at the Gate of India had been the Viceroy, Lord Reading, and a group of 10 be-jewelled Indian princes: and it is a central irony of this ill-conceived tour that most of the Imperial heir’s time was not spent in “British” India at all.

It was spent in the “other” India – that of the dozens of small independent native states that made up two-fifths of the sub-continent’s territory and a third of its population. Their rulers had to be thanked for their loyal contributions to the war effort, and they had to be encouraged as a vital bulwark for the British crown against radical demands for full and immediate independence.

A pattern was established of a cluster of princely states serving as steppingstones from one piece of British India to another. The royal party – to save both time and money – always travelled at night, in a purpose-built train of the utmost luxury. There was also a pattern to what the states set out to provide: extravagance, feasting and killing. And they vied with each other as to how lavishly they provided them.

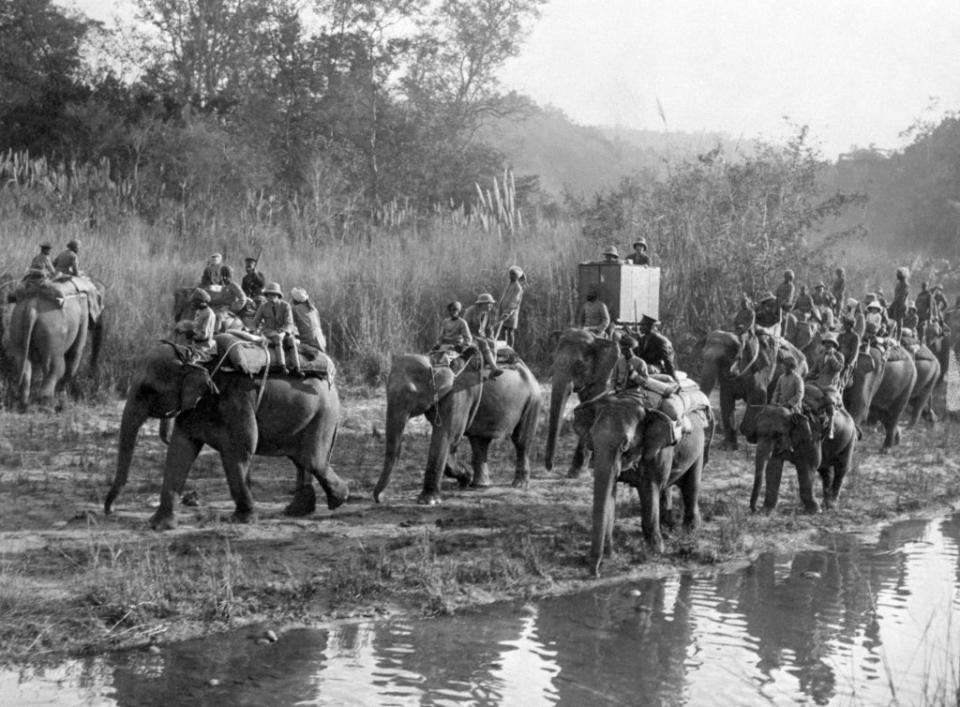

In Baroda there were state carriages of solid silver and a cheetah hunt. In Jodhpur there was pigsticking with Edward making his first kill. In Bikaner three out of five days were devoted to shooting sand grouse and demoiselle crane. In Bharatpur the prince rode in a silver carriage harnessed to eight elephants, while Louis Mountbatten was taken out hunting in one of the Maharaja’s dozen or so Rolls-Royces. In Nepal a special road had been built to give private access to a stockaded area of jungle: the royal week there cost the lives of 14 tigers, seven rhinoceros, two leopards and a couple of bears.

It seems clear that Edward disliked the bloated ceremony that characterised almost every day of his progress through princely India. He was marketed as having two dominant qualities: he was a sporting prince, and he was a soldier prince. The former meant that he liked nothing better than shooting wild animals: the latter that he had seen active service during the First World War. Neither was true.

The question of sport was unimportant, although on occasion his reluctance to kill animals could be socially embarrassing. (The only physical activity he really liked was polo, at which he was very skilled.) But the assumption that he had been a heroic soldier was, for Edward, tantamount to perpetrating a fraud.

He had spent the war trying desperately to persuade his father, King George V, to let him fight; and he hated the fact that being heir to the throne meant that he was protected from any danger. He was given a commission in the Grenadier Guards and was even sent to France to gain some military experience. But he was never allowed anywhere near the front.

That he spent much of his time on the sub-continent meeting, thanking, and decorating Indians who had fought for the Empire with great bravery in both Flanders and Mesopotamia – and consoling bereaved relatives of those who had died – was a constant reminder to him of his unusual and often unwanted privilege.

He was a slight man, thin, only five foot seven inches tall, and there are innumerable photos from the tour of India showing Edward garbed in the most extravagantly ornate military uniforms, bedecked with medals and with his head weighed down by huge hats or helmets. He looks like a boy who has gone to the family costume chest only to find that everything in it is too big for him.

But much as he might rail against his own position, there was nothing progressive or democratic about Edward’s views. At home he was contemptuous of Labour politicians and dismissive of suffragettes: while in India he made no secret of his passionate commitment to Empire and to the indefinite maintenance of British rule.

No wonder then that his sojourns in British India were uncomfortable ones. “It is regrettable to have to record the fact that Allahabad has failed in its welcome to the prince”, wrote The Times of India on December 13. “There is no use blinking the fact that the non-co-operators have scored their first success. The population of the city is more than150,000 but only a few thousand had assembled and of these the majority were Englishmen and Anglo-Indians. At the university, where an address of welcome was presented to the prince, there were only a bare couple of hundred students present.”

“I’m afraid I prefer native states to British India,” was Mountbatten’s snooty comment after being offered a dinner he didn’t think was quite up to scratch.

It was in Madras that the prince’s party had its closest encounter with hostile opposition. Rioters managed to infiltrate the European quarter and get close to Government House as Edward arrived. The pro-Raj daily, The Pioneer, had a reporter on the ground who described how decorations were transformed into weapons. “The crowd tore away the palms, smashed the flowerpots and used the debris as brickbats to be hurled at any passing car which contained a European. It is now midday, and the Leinsters are clearing the streets at the point of a bayonet. At the corner of the streets armoured cars stand menacingly.”

From his bedroom window in Government House Mountbatten was able to witness a cinema being set on fire because its owner had taken the risk of putting up some Union flags. “Another set of rioters overturned a tram,” he recorded; “three armoured cars leapt down the road and opened fire with their machine guns, accounting for several rioters.”

The local press reported a death toll of five or six. Not many, perhaps, but enough for The Pioneer to conclude that “Madras in a sense stands ashamed”. More to the point was the official report sent to New Delhi by the government of Madras after Edward had left town. It was bravely and surprisingly honest. “Though the actual reception accorded to His Royal Highness was most gratifying, this government remains of the opinion that the whole visit was regrettably inopportune and that very little permanent good can be expected to result from it.”

Almost two months later, as Edward finally came to the end of his tour in what is now Pakistan, these words could be taken as an epitaph for the whole project. After Madras he had got back on the native states trail that had him feasting and killing up through the heart of the sub-continent: Mysore, Hyderabad, Indore, Bhopal and Gwalior: then to Delhi, and finally into the Punjab and to the North West Frontier.

That Mahatma Gandhi was rearrested and sent back to prison a fortnight before Edward left India sums up the failure of his tour

It must have been an almost schizophrenic experience. On the one hand he was in regular receipt of gushing praise that bordered on adulation. At the state banquet in Delhi, Viceroy Reading referred to him as “a great Imperial asset and the most popular of his father’s subjects”; the Maharaja of Patiala said his personality combined “the unique qualities which will one day make him an ideal monarch”; while the great cricketer Ranjitsinhji, the ruler of Nawanagar, welcomed Edward as “the loveable, the tactful and experienced ambassador of fellow-feeling and friendship between all the scattered parts of the Empire”.

On the other hand, British India became an increasingly hostile place for him. In Nagpur there were “processions of schoolboys” marching through the streets “singing songs advocating a boycott of the Royal visit”; in Peshawar the prince’s speech was drowned out by organised shouts of Gandhi-Ki-Jai; and in Lahore, the capital of the Punjab, he needed serious military protection. The Pioneer reported that 3,000 troops were stationed along the route from the station to Government House, and that “three aeroplanes kept observation on the crowd, and five motor lorries, filled with armed infantry, equipped with Lewis guns, as well as three tanks, were ready to proceed to any threatened point”.

That Mahatma Gandhi was rearrested and sent back to prison a fortnight before Edward left India sums up the failure of his tour. He had been sent to heal divisions, to convince Indians – whether the mass of ordinary citizens or their political elite – that the sub-continent’s future could only be within the British Empire and that there was no need for extremist opposition or talk of independence.

In fact, what he had achieved was what British Tory opponents of his trip had said all along – the entrenchment of nationalist convictions and increased intolerance with the Raj. Put simply, he had made being British in India a more difficult and more unpleasant experience: and he had given a boost to those who opposed any further liberalisation of the Raj. Also, and despite his privately expressed distaste for the bloodthirsty excess of their lifestyles, he had hugely bolstered the political position in India of the Native Princes.

They had grasped the opportunity of proving themselves the Empire’s best Indian friends; and they had ensured their place in the complex political end-game that was to unfold in the sub-continent over the next 15 years.

Edward finally sailed from Karachi on 18 March, and a few days later Viceroy Reading received a letter from his predecessor Lord Chelmsford. “I must congratulate you on the successful termination of the prince’s visit. His departure in safety must have lifted a great load of anxiety from your shoulders.”

Indeed! But there is a tantalizing possibility that the tour might have taken a very different course. In March 1938, as Bhupinder Singh, the influential Maharaja of Patiala, lay dying in his palace, the politically astute British travel writer Rosita Forbes happened to be there researching a book, and found herself among a group of Indian princes gathering in anticipation of Bhupinder’s death.

Over long dinners they discussed the future of India and Forbes wanted to find out what they thought of Gandhi. This was what she recounted. “One of the Maharajas said, ‘he is very human you know’. The Prince of Wales understood that. Before he landed in India for his official visit, he sent a wire to Viceroy Reading asking that Mahatma Gandhi should be invited to have a conversation with him on board. The Viceroy deplored such unconventionality. The prince insisted that everything could be satisfactorily arranged if the two of them could meet privately before the official landing which was to be the signal for widespread civil disobedience.

“Somehow the prince was dissuaded and the visit was a disaster, as you know. I talked to the Mahatma about it afterwards and I asked him what would have happened had he received the prince’s invitation. ‘I should have accepted it.’ And then? ‘There would have been no civil disobedience. He would have appealed to our hospitality; and we should have been obliged to receive him as a guest’.”

Read More

An odd kind of piety: The truth about Gandhi’s sex life

Pair of Gandhi’s glasses sell for £260k after being found in letterbox

Indian MP from Modi’s ruling party praises Gandhi’s assassin as a ‘patriot’, sparking outcry